Annie Etheridge truly belonged on the battlefield

“The world never produced but very few such women, for she is along with us through storm and sunshine, in the heat of the battle caring for the wounded, and in the camp looking after the poor sick soldier, and to have a smile and a cheering word for everyone who comes in her way. Every soldier is alike to her. She is with us to administer to all our little wants, which are not few. To praise her would not be enough, but suffice to say, that as long as one of the old Third shall live, she will always be held in the greatest esteem, and remembered with kindly feelings for her goodness and virtues.” –Color Sergeant Daniel Crotty 3rd Michigan Infantry

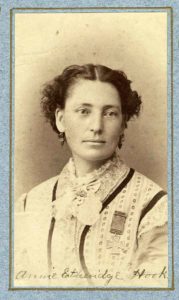

Accounts of women who dress in men’s uniforms and go off to battle are prevalent throughout the history of warfare. In folklore, these women often disguise themselves as men in order to fight alongside their husbands or lovers. But romantic as these stories sound, nearly all are apocryphal. Nevertheless, there are plenty of examples during the Civil War of women both North and South who served their respective armies in a no-nonsense and useful way. Of those, none surpassed Lorinda Anna “Annie” Blair Etheridge.

Annie was 21 and living in Detroit when the war broke out. Along with 19 other women, she joined the 2nd Michigan Infantry to serve as an unpaid vivandière—a woman who traveled with the army and generally saw to a wide range of soldiers’ needs. Within a few months, all the women but Annie had returned home.

Annie’s vivandière functions were many: She cooked for the soldiers, washed their clothes, wrote letters for them, nursed them when they were sick, tended their wounds during and after battles, and comforted them as they lay dying. Annie had worked as a nurse before the war, and she brought her considerable skill and experience to the battlefield. Some soldiers referred to her as “Michigan Annie,” but most called her “Gentle Annie,” possibly after the then-popular 1856 song by Stephen Foster. Her gentleness, however, could not mask her quiet strength and courage in the face of enemy fire.

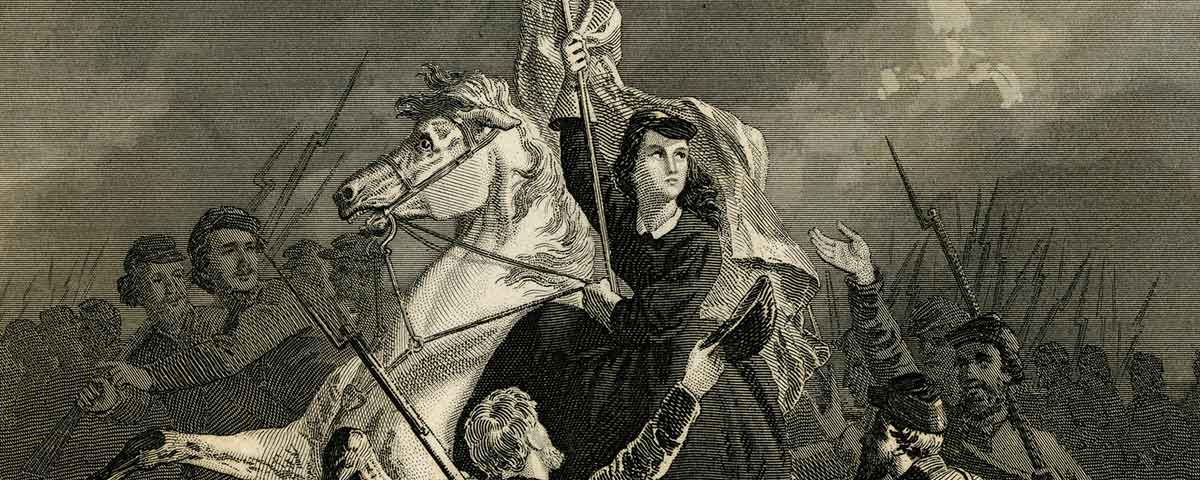

Nor did she retire to the rear when a battle began. According to an article in the February 28, 1863, Ottawa (Ill.) Free Trader: “At the commencement of a battle, she fills her saddle bags with lint and bandages, sticks a pair of pistols in her belt, mounts her horse, and gallops to the front, passes under fire, and, regardless of shot and shell, engages in the work of staunching and binding up the wounds of our soldiers.” She was, for all intents and purposes, a combat medic.

When Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny observed Annie tending the wounded under fire at the Second Battle of Bull Run, he swore to make her a sergeant, and assign her a horse. Kearny had no chance to fulfill his promise. He was killed at Chantilly, Va., on September 1, 1862, two days later, and although Annie was given the horse, she received no official appointment to a military rank.

According to one soldier with whom she served, “She is always to be seen riding her pony at the head of the Brigade on the march or in the fight. Genl. [Hiram G.] Berry used to say she had been under as heavy fire as himself.” Annie had tended Berry through a dangerous fever, and the two became fast friends. He so admired her that he asked her to escort his body home, should he be killed in battle. Shortly thereafter, he was shot dead by a Rebel sharpshooter at Chancellorsville on May 3, 1863, and it was forever Annie’s regret that she was unable to honor his request. “If he had been my own father,” she later wrote, “my grief could not have been deeper.”

As a nurse on the front lines, Annie witnessed unspeakable horrors. On one occasion, she was treating a wounded man when a shell literally blew him apart beneath her hands. In battle after battle, she emerged from the field unscathed—with one exception. It was at Chancellorsville that Annie received her only wound. As the enemy line opened fire, a mounted officer took shelter from the Rebel guns by hiding behind Annie. Incredulous, she turned to look at him, just as he was shot from his horse. Another ball grazed Annie’s hand and struck her own horse. The animal took off at a dead run, with Annie clinging desperately to the reins. Finally, a soldier of her regiment stopped the runaway, while the others cheered her.

Countless letters written by soldiers to their loved ones at home mention Annie with affection and gratitude. Perhaps the most poignant was a letter written to Annie herself by a dying Ohio soldier.

January 14th, 1864.

Annie—Dearest Friend: I am not long for this world, and I wish to thank you for your kindness ere I go.

You were the only one who was ever kind to me, since I entered the Army. At Chancellorsville, I was shot through the body, the ball entering my side, and coming out through the shoulder. I was also hit in the arm, and was carried to the hospital in the woods, where I lay for hours, and not a surgeon would touch me; when you came along and gave me water, and bound up my wounds. I do not know what regiment you belong to, and I don’t know if this will ever reach you. There is only one man in your division that I know. I will try and send this to him; his name is Strachan, orderly sergeant in Sixty-third Pennsylvania volunteers.

But should you get this, please accept my heartfelt gratitude; and may God bless you and protect you from all dangers; may you be eminently successful in your present pursuit. I enclose a flower, a present from a sainted mother; it is the only gift I have to send you….I know nothing of your history, but I hope you always have, and always may be happy; and, since I will be unable to see you in this world, I hope I may meet you in that better world, where there is no war. May God bless you, both now and forever, is the wish of your grateful friend.

George H. Hill

Cleveland, Ohio

Strachan himself was killed before he had the opportunity to give Annie the letter. It was found on his body and delivered to her.

Annie served with the 2nd, 3rd, and 5th Michigan throughout the war, beginning at Blackburn’s Ford, Va., in July 1861. And though she was one of only two women awarded the prestigious Kearny Cross of Valor, she neither sought nor received payment for her extraordinary service.

After the war, she worked for the Treasury Department, but was soon replaced by a male. In 1886, she requested a $50-a-month pension from Congress, as a stipend in recognition of her war service—she would be awarded half that amount. Upon her death on January 23, 1913, Gentle Annie was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery alongside her husband, a one-armed veteran of the 7th Connecticut Infantry. On the tombstone below her name it simply says, “Nurse.”

Ron Soodalter writes from Cold Spring, N.Y.