It is no secret that health care during the Civil War was rudimentary at best. Most of the 750,000 or so deaths suffered during the conflict occurred because of illness, disease, or infection. And at a time when amputation was common in the treatment of wounded men, hospitals were not known for their solicitous or effective treatment of the stricken. Therefore, when an unassuming young Virginia woman opened her own private hospital for the care of Confederate soldiers, people had every reason to presume that it wouldn’t differ at all from the others. They were wrong.

From the moment of her birth in 1833 at Poplar Grove, her family’s Mathews County estate in Virginia’s Tidewater region, Sally Louisa Tomkins lived a life of privilege. By the outbreak of the war, her father had died, and Sally was living in Richmond with her mother. Reportedly, from early childhood she showed both an inclination and an aptitude for nursing, and in the immediate aftermath of the First Battle of Manassas in late July 1861, she determined to dedicate her inheritance—and her life—to the care of Confederate wounded.

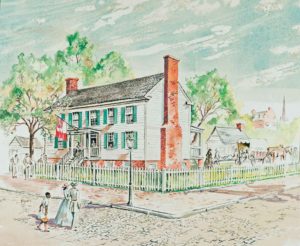

Tompkins immediately acquired and converted the Richmond home of Circuit Court Judge John Robertson, at the corner of 3rd and Main streets. She immediately bought medical supplies and outfitted what she named the Robertson Hospital in top-drawer fashion. Tompkins staffed the hospital with women—all fellow members of the St. James Episcopal Church—who called themselves, appropriately, the “Ladies of Robertson Hospital.”

Within a short time, word of Tompkins’ compassionate demeanor and highly effective treatment methods—which were grounded in strict adherence to a regimen of cleanliness—spread throughout the Rebel ranks. According to one source, “Wounded soldiers coming to Richmond begged to be admitted to her hospital.”

Unfortunately, many of the “disabled” soldiers were in fact malingerers, bent on using long stays in the South’s hospitals as a means of avoiding camp chores and combat. To counter this practice, the Confederate government passed a measure placing all hospitals under the administration of the military. As a result, private hospitals were forced to close their doors.

According to various historians, Tompkins appealed directly to President Jefferson Davis, and—based on her hospital’s outstanding reputation—he commissioned her a captain of cavalry in the Confederate Army, thereby enabling her not only to remain in operation, but to draw her medical supplies from military stores. Although she refused to accept the officer’s pay that accompanied her new commission, Tompkins held the distinction of being the only woman knowingly commissioned as a woman (and not a woman soldier posing as a man) ever to hold officer rank in the Confederate Army.

The hospital maintained an extraordinary survival and recovery rate, inspiring numerous commanders to send her their most critical cases. Still, things did not always go smoothly. The South was consistently short of everything from food, blankets, and clothing to medical supplies. But Tompkins always made do, generally spending her own money to make the necessary purchases.

She also demonstrated considerable grit in confronting threats to her institution. In June 1864, a Confederate military inspector of hospitals named Carrington took it as his mission to close down the Robertson Hospital, claiming that it was filled beyond capacity. In response, Tompkins wrote to the authorities that his assertion of overcrowding “was written under a misapprehension of the facts,” adding, “I think the register of this Hospital will show as great success in its management of the sick and wounded as any other. Since the 1st of last June, we have had 337 patients and but 8 deaths. Many of them sent to us were…the wors[t] cases.” Needless to say, the hospital remained open.

The soldiers adored Tompkins, dubbing her “the Angel of the Confederacy,” “the Little Lady with the Milk-White Hands,” and most commonly, “Captain Sally.” One source records that she “saw that every discharged patient received clean clothes, rations and a Bible.” Love-struck patients often asked for her hand in marriage, but she always refused, commenting, “Poor fellows, they are not yet well of their fevers.”

At war’s end, Tompkins kept her doors open, releasing her last patient on June 13, 1865—two months after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Although most of the Confederacy’s records in Richmond were burned, one statistic remains indisputable: During its 45 months in operation, the Robertson Hospital treated 1,333 soldiers and lost only 73, reflecting a survival rate of 94.5 percent. This is a remarkable record, especially considering the time and conditions.

After the war, Captain Sally remained active in the affairs of the Episcopal Church and enjoyed a certain celebrity as a frequent guest at reunions and other functions. Between June 30 and July 2, 1896, the Grand Confederate Reunion took place in Richmond. As part of the observances, a reunion of Tompkins’ former patients was held at the hospital. Several old soldiers attended and were once again treated to the solicitousness of their former nurse. According to the historical records at the Library of Virginia, to mark the occasion, “Sally Tompkins rented a house and provided food and drink for former patients of Robertson Hospital and their families.”

Tompkins entered old age virtually penniless, however. She had spent most of her inheritance in the maintenance of her hospital and on several other philanthropies, and—according to one source—financial reverses took the rest. She was invited to enter the Richmond Home for Confederate Women, where she resided as both matriarch and honored lifetime guest.

Captain Sally never married, despite the many proposals from her grateful and adoring patients. She lived well into her 82nd year, dying on July 25, 1916. The next day’s Richmond Times-Dispatch noted, “Captain Sally Louisa Tompkins, 83 years old [sic], died yesterday of chronic nephritis at 8:45 o’clock in the morning….The funeral, with full military honors, will take place in Mathews County….”

Four United Daughters of the Confederacy chapters have been named in Sally Tompkins’ honor, and there is a memorial to her in the Mathews Court House Square. At St. James Episcopal Church in Richmond, to which she dedicated so much of her time and resources, a stained-glass window features a full-size portrait of her holding a Bible and dressed in black, standing before an angel with arms extended protectively—a fitting tribute to the Angel of the Confederacy.