1777 American defeat in the Vermont mountains weakened the British, setting them up to lose at Saratoga

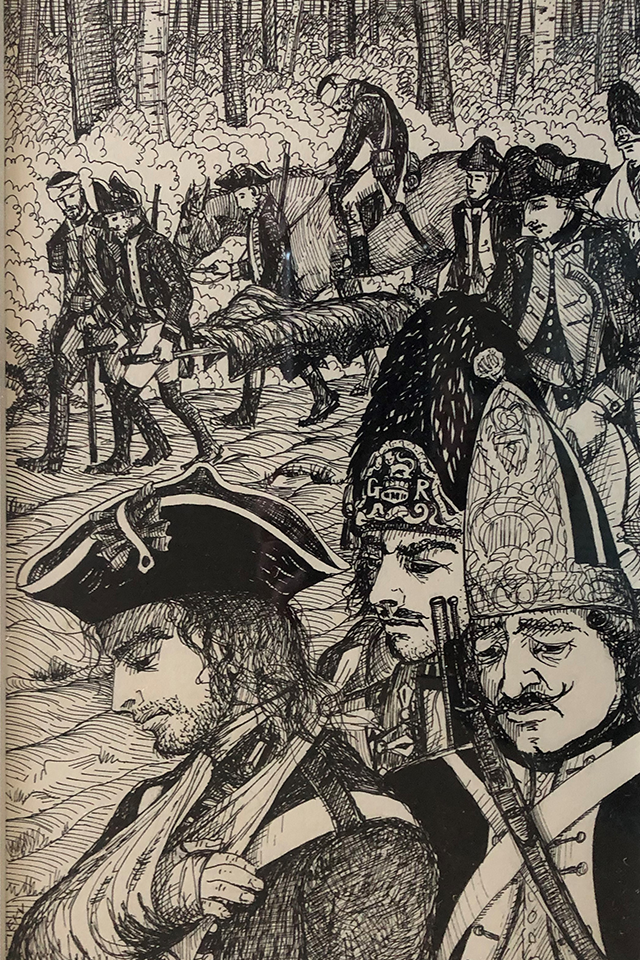

DAY WAS BREAKING in the wilds of what is now western Vermont on Monday, July 7, 1777, as two lines of British light infantrymen broke into a run up a steep, overgrown hill. That hot morning the soldiers had dressed for heavy going, in black leather caps and shortened red woolen uniform coats. At the lead was Brigadier General Simon Fraser. The Scottish-born Fraser, 48, meant to earn the trust his commander, Lieutenant General John Burgoyne, had shown in assigning him this mission. Ahead waited a rebel contingent Fraser intended to smash—which he did, in a stand-up, four-hour slugfest. The New England Continentals and militia got a harsh taste of their preferred mode of warfare, as a British officer observed, “in a wood, in the very style that the Americans think themselves superior to regular troops.” But while Fraser and his men won the day, the long game went to the foe. In that one midsummer clash may have lain the fate of a campaign, a war, and perhaps a country.

The ruling-class Britain of the late 1700s was an intimate world. John Burgoyne, 55, naturally knew King George III and his cabinet

ministers. An army officer since 14, Burgoyne had wed an earl’s daughter, marrying into a seat in Parliament, elbow room at London’s best gaming tables, and camouflage for his questionable parentage. In the Seven Years’ War, Burgoyne had made enough of a name that Portugal’s king, grateful still to have his throne thanks to Burgoyne’s battlefield victories, bestowed a five-carat diamond ring on the young general.

In February 1777, Burgoyne, after two previous campaigns in the colonies, sent King George III and Secretary of State for the Colonies Lord George Germain what seemed a surefire formula for ending an irksome rebellion of 27 months’ duration. British politicians and military commanders regarded the font of colonial resistance to be New England, in particular Boston, a scene for years of shenanigans like Stamp Act riots, a “massacre,” and the outrageous Tea Party—never mind that the war had begun nearby at Lexington and Concord. Scratch an act of violence against the empire and there one would find Massachusetts Bay colonists. Isolate New England, as a physician might quarantine an infectious patient, imperial wisdom went, and the rebellion would fade for lack of an inflammatory source.

To accomplish that isolation, Burgoyne proposed to make a moat of New York’s Hudson River, dousing the fires of rebellion by splitting New England from the middle and southern colonies. Describing “my expedition,” Burgoyne offered in an outline he circulated that February to sail an army south from Canada through Lake Champlain and Lake George as a prelude to capturing Albany, on the Hudson River’s west bank. Burgoyne sketched a force of British regulars, Loyalists, French Canadians, sailors, and Indian allies—in all, 9,078 men, including German hirelings from the principality of Brunswick. Major General Friedrich Baron von Riedesel’s 2,900 German regulars included green-jacketed jäger, a light infantry and scouting unit dating to 1740, when Frederick the Great recruited sharpshooters from among German foresters, and Brunswick grenadiers, renowned as masters of the bayonet, in striped trousers, blue coats, and mitered helmets. Burgoyne would have 138 artillery pieces. As he was sailing south from Canada, up from New York would come an army led by General Sir William Howe, British commander-in-chief in the colonies.

For Burgoyne’s plan to succeed, his and Howe’s cohort had to converge at Albany with a third, smaller force of redcoats, Loyalists, and Indians under Lieutenant Colonel Barrimore St. Leger. Invading from Lake Ontario, penetrating the Mohawk River Valley west of Albany, and capturing Fort Stanwix near what is now Rome, New York, St. Leger would press east to rendezvous with Burgoyne and Howe, giving the British control of the Hudson. Burgoyne would bring the celebratory Champagne, his favorite drink.

Obtaining the king’s nod for his expedition, Burgoyne organized his troops and departed St. John’s, Canada, south of Montreal. By June 16, 1777, he was sailing south on Lake Champlain in his flagship, the frigate Royal Savage, at the head of a fleet of troop transports, rowed

gunboats, and hundreds of 30-foot-long bateaux, the 18th-century equivalent of a flatbed truck to carry supplies. Native warriors in canoes darted among the naval vessels. Burgoyne’s first target was Fort Ticonderoga, a bastion on Lake Champlain’s west bank built by the French during the Seven Years’ War. Ticonderoga was held now by an American army under Major General Arthur St. Clair, 40, who had assumed command only two weeks previously. Spying a weakness in the American perimeter that would allow British artillery to shell the fort, Burgoyne’s chief engineer had two 12-pound cannon hauled to high ground atop Sugar Loaf—now Mount Defiance. The promontory was steep, but as Burgoyne’s second in command, Major General William Phillips, is said to have put it, “Where a goat can go, a man can go and where a man can go, he can drag a gun behind him.” The sight of British field pieces so strategically placed forced the rebels to prepare to retreat across a pontoon bridge to the east side of the lake where another rise, Mount Independence, had been fortified. At midnight July 5, St. Clair began sending his sick soldiers, camp followers, and supplies from Ticonderoga 25 miles by water to Skenesborough, New York, at the south end of Lake Champlain. Their transport was a fleet of 200 bateaux and six rowed galleys under Colonel Pierce Long. The remainder of the American army, nearly 3,000 men, would march 17 miles southeast from Mount Independence to Hubbardton, then six miles more to Castleton. At Castleton, St. Clair hoped to turn west toward Skenesborough and reunite with Long.

St. Clair’s rear guard, including stragglers, under Colonel Seth Warner, 34, would overnight at Hubbardton, then continue to Castleton, following in the wake of the retreating army. If all went according to plan, the entire American army would link up with the Northern Department’s commander, Major General Philip Schuyler, who had been toggling between his Albany headquarters and Fort Edward on the Hudson’s west bank, 38 miles south of Skenesborough. Unfortunately for the patriots, Burgoyne’s quick pursuit by water of Long’s fleet put a crimp in St. Clair’s plan. Long had to scuttle his boats and supplies at Skenesborough as British gunboats fired on the town and redcoats embarked along the shore. Long’s disaster compelled St. Clair in a different direction to Rutland, now in Vermont, adding 14 miles to the Americans’ march before they turned south to join Schuyler at Fort

Edward.

The Americans had left Ticonderoga and the lakeside high ground on July 6 as Fraser and his Advanced Corps marched into the fort and toward Mount Independence. Fraser’s elite unit comprised a light infantry battalion, a grenadier battalion, eight companies of Fraser’s 24th Foot and a sharpshooter company.

Opposite the fort, on the lake’s east side, Riedesel had disembarked with his Brunswickers. Burgoyne had remained on Royal Savage to coordinate his army’s two wings. Advising Burgoyne by courier of his intent to pursue St. Clair, Fraser readied his light infantry and grenadier battalions and two companies of the 24th Foot, 850 men in all, and quickly set out. In his haste, Fraser shorted his troops on ammunition, rations, medical supplies, and artillery. Receiving Fraser’s note aboard Royal Savage, Burgoyne ordered Riedesel, 38, with 1,100 Germans, including jäger and grenadiers, into the chase.

Reaching Hubbardton on the afternoon of July 6 after marching through a saddle on Sargent Hill, St. Clair stationed a rear guard of

about 900 men under Seth Warner. Warner’s complement soon swelled with 300-some stragglers. Hubbardton was an isolated farming community of nine hardy families situated in the Hampshire Grants, a contested wilderness between New York and New Hampshire. The “Grants,” as locals called the district, consisted of small farm lots, forested mountains, and a few towns like Castleton, Rutland, and Manchester. Populated mostly by New Englanders eager for cheap land, the Hampshire Grants had been the scene of feuding neighbors for years before the revolt against Great Britain. Gangs of quasi-outlaws known as Green Mountain Boys, led by Ethan Allen, warned New Yorkers against planting themselves in the few select meadows and thick forests soon to be called Vermont.

Near dawn on July 7, after a night of rest and food for the stragglers, Warner massed most of his men on a road below the crest of what is now called Monument Hill, preparatory to marching for Castleton. To Warner’s left was a higher hill, Pittsford Ridge. Warner’s officers were at Sucker Brook, chivvying disorganized stragglers, some of them drunk. To the west, an American picket fired his weapon, a signal that British troops were closing. Advancing along the military road toward the brook, elements of Fraser’s 24th Foot caught a hail of American musket fire that killed the major leading them and depleted his two companies. Fraser pushed forward with Major Alexander Lindsay’s light infantry battalion. Lindsay being new to combat, Fraser took command, facing the battalion left and advancing at the double up Monument Hill, where, on the opposite slope, Warner’s regiments, in column, were poised to march to Castleton.

Fraser undoubtedly was seeking to achieve a precipitous victory before Riedesel, who outranked him, arrived to supersede him on the battlefield.

Warner and Colonel Ebenezer Francis, 34, quickly faced their troops right and advanced unsteadily. At the hill’s crest, redcoats charged hard into the Americans, forcing them down to what Fraser later termed a “hill of less eminence.” The rebels rallied, trading volleys with the foe at the murderous range of 60 yards. Below, at the brook, a British grenadier battalion led by Major John Dyke Acland captured most of the American stragglers, then marched beyond the British right flank to deny Warner’s men the Castleton road. With two companies of light infantry leading, Acland rushed through a swale between two hills along the military road. Gaining the Castleton road, grenadiers pushed back Warner’s own Green Mountain Continental regiment.

Americans mauled in the British hilltop charge had pulled back to a cornfield enclosed by a high U-shaped log fence. Briefly hunkering there, Warner’s men, Francis’s command, and troops from Major Benjamin Titcomb’s 2nd New Hampshire regiment all came under determined attack. Acland’s grenadiers hit Warner’s left and Lindsay’s light troops in the center facing Francis and Titcomb’s line. Some of Lindsay’s detached light infantry gained Pittsford Ridge; putting British muskets behind the Americans at the log fence. Warner tripped and fell; men thought him shot. Francis took a ball in the chest. Titcomb’s New Hampshire men counterattacked, momentarily imperiling Fraser’s left flank. The tilt was decidedly against the rebels, but British casualties were mounting. Fraser frantically summoned Riedesel. From his trailing column, the German shoved forward two elite units. Captain Carl von Geyso’s green-jacketed jägers led, followed by Captain Maximilian von Schotellius’s Brunswick grenadiers. Observing from Sargent Hill, Riedesel decided to flank the American right. He ordered the jäger drummers and hunting hornsmen to blare hymns; as the Europeans advanced, his soldiers bellowed the lyrics, unnerving the Americans.

Jäger riflemen and Brunswick grenadiers surrounded Titcomb’s flank and rear. Riedesel’s troops guaranteed Fraser victory, but not without snide commentary by their employers. “A party of Germans came up [in] time enough also to share [emphasis added] in the glory of the day,” a British officer wrote later. “The regular fire they gave at a critical time was material service to us.” The Germans had been of more than “material service”—they crushed a move by New Hampshire troops and others threatening the tottering British left flank, driving the rebels off the field. Seeing Titcomb’s and Francis’s lines give way, Warner, knowing the battle was lost, “poured out a torrent of execrations upon the flying troops,” a fellow officer said later. With Francis down, Titcomb wounded and his right flank enveloped, and himself stunned by the onslaught of British grenadiers on his left, Warner called it a day. “Scatter and meet me in Manchester!” he shouted, triggering a scramble down the east side of Monument Hill. Americans fled up and over Pittsford Ridge toward Manchester. One man “took a tree and waited for them to come within shot,” a rebel said later. “We fought through the woods, all the way to the ridge of the Pittsford mountain, popping away from behind trees.”

This stuttering withdrawal meant the battle “lasted near three hours, before they attempted retreating, with great obstinacy,” a British lieutenant wrote afterwards. The only remaining resistance was scattered rebel sniping, silenced as the British and Germans mopped up. The victors fashioned huts from bark to shield the many wounded from a brutal sun. Late in the day a torrential rain cooled the area.

On July 8, while the redcoats dressed wounds and buried the dead, the Germans, at speed, made for Skenesborough, 18 miles away. Told that Riedesel’s troops had set a fierce pace, Fraser cracked, “[Riedesel] made a march rather more rapid than when he moved to my support.” Unable to relocate his own command because he lacked provisions and ammunition and fearing a counterattack—scouts reported that the Americans “were gathering strength hourly”—Fraser set able-bodied prisoners to building log defenses around his camp. He need not have bothered; surviving rebels were hightailing it for Manchester and Rutland.

British troopers now plundered whatever Americans, dead or living, had not been able to escape from Hubbardton, relieving prisoners, corpses, and wounded men of personal and military effects. One officer noted, “great quantities of paper money [was taken] which was not the least regarded then, tho had we kept it, it would have been of service, as affairs turned out.”

Hubbardton cost the Americans 375 men: 41 killed, and 96 wounded, with 238 recorded as captured. British and German casualties totaled 218, with 60 British and 10 German dead. The British had 134 wounded and the Germans 14; no redcoats or Brunswickers were captured. Most of the rebels captured were sick, disabled, or unmanageable stragglers—no great loss to the American ranks.

However, after crushing the American rear guard, the British failed to pursue; 67 percent of the surviving rebel soldiers escaped. In those brutal hours at Hubbardton, Warner and his men saved St. Clair’s army from having to tangle with Burgoyne’s. Warner knew his men, knew the ground they were fighting on, and knew their condition after a forced 20-mile march. Resting the night before the battle had allowed the American rear guard to be able to give as good as they got, if only temporarily, and in the process buy the precious time that St. Clair’s equally tired and demoralized army so badly needed. The sacrifice at Hubbardton let St. Clair get his men out of harm’s way and, in time, rally with Schuyler’s forces at Fort Edward. Reinforced by St. Clair’s men, Schuyler implemented a delaying strategy focused on denying the British control of the road to Albany. He also was depriving Burgoyne’s army, whose supply line stretched to Canada, of sustenance usually obtained from foraging locally. As much as any battlefield reverses, logistics defeated Burgoyne, an eventuality that Warner’s action at Hubbardton cemented.

Burgoyne’s losses at Hubbardton irreparably damaged his army, already thinned by ordering men to garrison Fort Ticonderoga and other captured outposts. This continuous stripping away of personnel, essential to maintaining his attenuated supply line, also wore at Burgoyne’s combat readiness. When Fraser’s Advance Corps fought at Saratoga in September, Burgoyne badly missed the crack troops, the grenadiers, and the light infantry who had been cut down at Hubbardton. On October 17, the American general Horatio Gates accepted Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga, a defeat historians have long considered the hinge of the War of Independence, swinging France to the rebel side. It is not too much to speculate that Seth Warner’s stand at Hubbardton may have been the rear guard action that saved America.

_____

After Hubbardton

In August 1777, Brunswickers under Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum left Burgoyne’s army south of Fort Edward to raid Bennington, Vermont. The town was being defended by American under Brigadier General John Stark. Stark called on Seth Warner to defend Bennington’s supply depot. Augmented by Warner’s men, Stark met Baum’s Germans, Loyalists and Indians five miles west of Bennington on the Walloomsac River. Stark soundly defeated Baum—perhaps an “ample revenge on account of the quarrel at Hubbardton.”

Life on the frontier during wartime soon had Warner struggling with “complicated and distressing maladies, which he bore with uncommon

fortitude and resignation, until deprived of his reason.” He was 42 when he died on December 26, 1784. Fraser, his adversary at Hubbardton, was mortally wounded in the abdomen at Saratoga on October 7, 1777, and died the next day. At his request, Fraser was buried in Burgoyne’s fortified line called the Great Redoubt. General Riedesel surrendered at Saratoga with Burgoyne. Briefly confined at Boston on parole, the Englishman returned to London the following year. The German remained a prisoner until October 1780, passing through Long Island and Quebec on the way to his native Brunswick. After six years’ service under the Duke of Brunswick, Riedesel retired to his castle at Lauterbach to write his memoirs. He died in his sleep on January 7, 1800. He was 62.

Among Hubbardton’s casualties, the luckiest may have been British major Alexander Lindsay, 6th Earl of Balcarres. Struck by “a musket ball that could have shattered his femur in his left leg,” Lindsay wrote later that the round “glanced off a flint in his pocket and left him with only a slight flesh wound and contusion.” Another round carried away the barrel and lock of Lindsay’s musket as he held it. The young earl counted ten bullet holes in his uniform. “You may observe,” Lindsay wrote his sister, “on this occasion I am not born to be shot whatever may be my Fate.” Captured at Saratoga and held until 1779, he survived the war, dying in 1825 at age 73. Major Acland, 31, the grenadiers’ commander, was not so lucky. Slightly wounded at Hubbardton, he was shot though both calves at Saratoga on October 7, 1777. Lindsay recovered in England only to succumb a year later to a cold caught during an early morning duel.

General John Burgoyne—“Gentleman Johnny”—as George Bernard Shaw dubbed him in his 1897 play, “The Devil’s Disciple,” set in America during the Saratoga campaign—survived the war. Himself a late-life success as a dramatist, Burgoyne wrote and saw produced a series of popular plays. He was 70 when he died in London in 1792. —Bruce M. Venter