IT WAS THE MOST MISERABLE night of my life.

Hours earlier I’d bailed out of a burning B-17 somewhere over Germany. One member of Ole Worrybird’s crew was dead, another had jumped out before the rest and vanished, and our copilot had broken his leg upon landing and been hauled off by German soldiers. Now the remaining six of us sat cold and shivering in a horse stall, exchanging frightened glances. Sleep was almost impossible. German guards outside the door made sure we stayed there through the night. We cursed our bad luck, thinking about the rest of the 95th Bomb Group flying home to England and warm barracks.

Ole Worrybird was the bomb group’s only casualty that November 2, 1944, damaged by flak and then downed by a Focke-Wulf 190 fighter after bombing one of Germany’s most dreaded targets: the heavily protected Leuna oil refinery near Merseburg, Germany. The German soldiers who encircled us on the ground had us gather our parachutes and march down a country road to a small garrison. There, our captors first relieved us of anything valuable, including the watch my mom and dad had given me as a high school graduation present. They also took away our fleece-lined flying suits, leaving us with only flight boots and our regular olive-drab wool uniforms. And they removed one of the two dog tags we wore around our necks. Then we had a meal of cabbage soup—cabbage would become a mainstay for the next six months—and spent the night in the horse stall from which the horse (and only some of his droppings) had been recently removed.

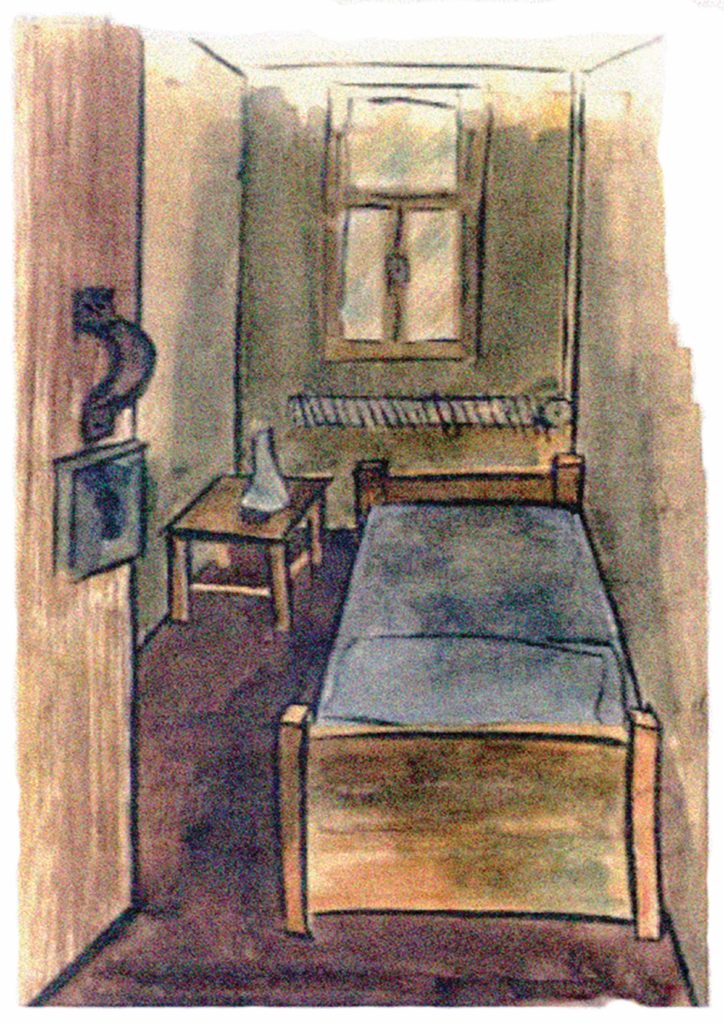

The next morning, with two armed guards, we departed on what turned out to be a five-day tour of wartime Germany, traveling by an exhausting mixture of bus, train, streetcar, and on foot, before arriving at our destination: the Luftwaffe interrogation center—or Auswertestelle West (Evaluation Center West)—near Frankfurt. Here we were placed in solitary confinement cells to await questioning. Just before a guard pushed me into my cell, I asked him if I could have something to eat, but he acted as if he didn’t understand English. I learned later that the guards understood English very well but were instructed not to communicate with prisoners—just to listen and report any information of value.

The purpose of solitary confinement, of course, was to break us down, to get us to tell everything we knew about the 95th Bomb Group. Then I thought: Well, this will be a good chance to just sit and think about things. And I did plenty of that.

ON THE FOURTH DAY OF SOLITARY, the guard opened my cell door and directed me to follow him to an adjoining office building. We passed a few closed doors before the guard knocked on one. A voice from inside said, “Herein!” (enter). My guard opened the door and directed me in. There, a large desk stood in front of a curtained window with warm sunshine flowing through. Behind the desk sat a smiling Luftwaffe officer dressed in an immaculate uniform. He was a well-built fellow, rather good looking, and appeared to be about 50. His light brown hair was combed straight back. Compared to muddy, unwashed me, the man was a movie star—an actor in a Nazi uniform.

As I entered his office, he stepped around his desk, walked up to me with his hand extended, and in excellent English said, “Ah, Sergeant Livingstone, please sit down.” He shook my hand firmly and gave me a fatherly pat on the shoulder. Then he walked back around his desk again and sat down, all the while with a warm smile on his face. After offering me a cigarette, he reached into a desk drawer and pulled out a printed form of some sort and picked up a fountain pen.

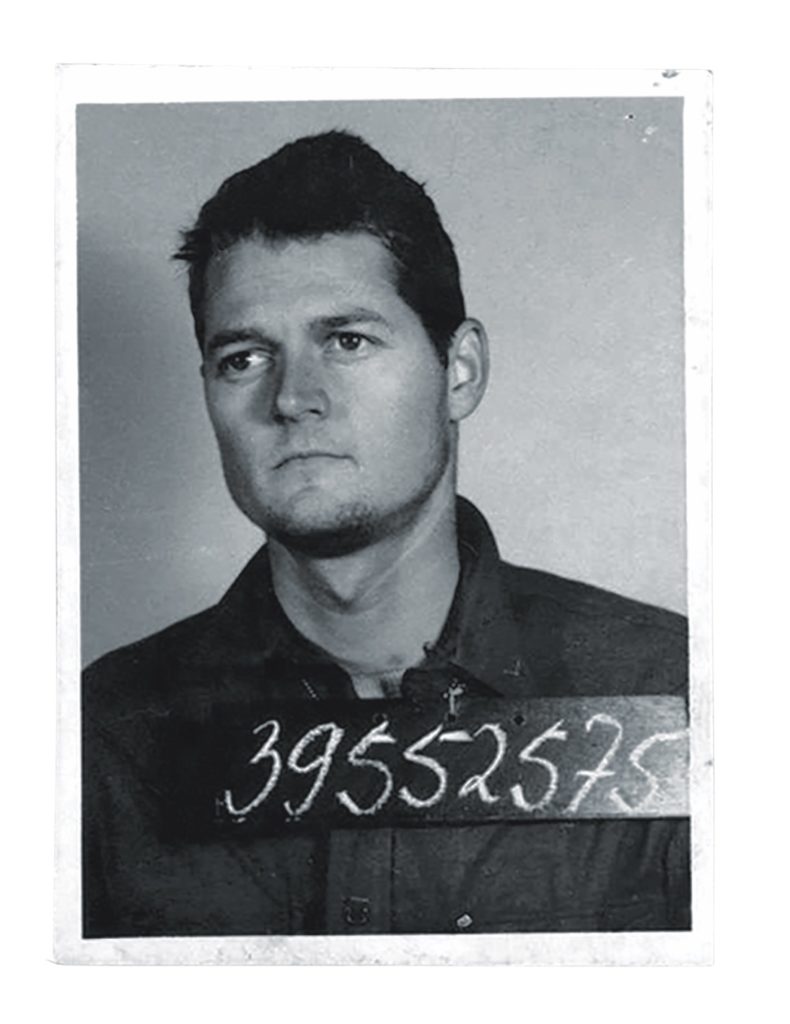

He asked me for my name, rank, and army serial number. All that information, except for my rank, was on my extra dog tag, lying right there on his desk. But I suppose he needed to confirm I was that tag’s owner. Then he went out of bounds: he asked me what bomb group and squadron I was with. I told him I could only give him my name, rank, and serial number.

He smiled again, this time with a little expression of superiority: “That’s all right, we know you were in the 95th Bomb Group.” Of course they did. The block letter “B”—the 95th Bomb Group’s emblem—was eight feet tall on the tail of our B-17. The Fw 190 pilot who shot us down couldn’t have helped seeing it.

“What was your target the day your airplane was shot down, please?” he asked next, still smiling. Again, I said, “I can only tell you my name, rank….”

“Sergeant Livingstone”—he cut me off as sternly as my own commanding officer would have—“without your cooperation I don’t know how long you will have to remain here in solitary confinement, and you won’t be able to go to the nice camp.” He was frowning now. So was I.

He proceeded to ask other questions related to the military strength of the 95th Bomb Group, and to warn me that I was going to have to stay in that six-by-ten cell until I told him what he needed to know. Finally, after about 15 minutes, he pushed a buzzer on his desk and the guard came back into the room. The officer said something to him in German and offhandedly gestured for me to follow the guard out and back to my cell.

Two days later I was escorted back to the same officer. This time he was quite curt. He asked me all the questions for which he had no answers and again warned me that I wouldn’t be transferred to the “nice camp” until I helped him fill out his form. This interview lasted only about five minutes, and he gained no more information. Nonetheless, that afternoon, after five full days in solitary confinement, my crewmates and I were shipped out to the promised camp, about 45 miles north.

It was a transit camp run by the International Red Cross—with no German guards on the inside, but under the watchful eye of Luftwaffe guards on the outside. Here, after what turned out to be the last shower I would have for almost six months, we changed from our dirty uniforms, some of them ragged and bloodstained, into new olive-drab winter uniforms, new G.I. shoes, new underwear, knit fatigue caps, heavy overcoats, and wool scarves knitted by some dear ladies back in the States. That brown wool scarf and I became close friends for the next few months, through one of Europe’s coldest winters.

We stayed there just six days, leaving on November 19 by train for what turned out to be Stalag Luft IV, near the Baltic Sea in what is now northern Poland. At one point on the four-day trip, our train stopped rather suddenly, and we saw the crew leap from the engine and dart into the adjoining woods. About half the guards fled there as well. At the same time, we heard the roar of aircraft above the tracks. We could see them—American P-47 fighters—when they zoomed up to make an attack on the nearby town. The train had a large “POW” insignia on the top of one of the cars and so was not strafed, but we could hear the boom of antiaircraft guns firing nearby.

Sometime later, while I was gazing out the window on the south side of the train, we crossed an at-grade roadway. Beside the road I saw a little sign with an arrow pointing north. It read, “Merseburg — 10km.” That’s about six miles. Merseburg was our target that fateful day, almost three weeks before, when the Worrybird was shot down. I glanced out the north side of our coach and in the distance, across a flat plain, I could see the outline of the oil refinery. Beside the road I could also see bomb craters. I wondered if any of them had been created by the bombs I toggled out of our B-17. (I was the nose gunner and what we called the “togglier,” meaning I operated the toggle switch that dropped the bombs.) Whose ever they were, they missed by a lot.

ON THE FOURTH DAY, our train finally stopped at a tiny station at Kiefheide, near Gross Tychow (now Tychowo, Poland). My fellow POWs and I marched two miles to our new camp, built just six months before.

Stalag Luft IV—a camp for American and British airmen NCOs—was composed of four double barbed-wire fenced compounds, or lagers, A through D, with guard towers located about 200 feet apart along the fence lines. About 20 feet inside the barbed-wire fence was a warning wire, mounted on stakes about two feet above the ground. Crossing the warning wire made you fair game to get shot when guards spotted you. The camp was home to nearly 8,000 U.S. Army Air Forces POWs and another 900 from the British Royal Air Force. In each lager (I was in Lager B), 10 large barracks stood in military array; in each barrack were 10 20-foot square rooms. Each room housed 25 men—men whose part in the war was complete and who could only await its end.

During the day, we were allowed to roam free in the compound, but our guards locked us in our barrack at night while they patrolled the area with guard dogs. The double-deck bunks held straw-filled mattresses that lay flat and hard on the boards shortly after being fluffed up. My room—Room 10—had knotty pine walls that resembled what were later in the den in my Santa Barbara home. There was one casement window with outside shutters, which the guards closed and locked at night. Outside the shuttered windows, bright lights flooded the compounds. Anyone found outside at night would be shot on sight.

Near the door was a potbellied stove in which we burned pressed wood and coal dust pellets about the size of golf balls. Because we were given only a limited amount, we carefully rationed this fuel and used it only during the daytime, to keep the place semi-warm in that frigid winter. The floors were always cold then because they were built about four feet above the ground. This was to allow the guards and their dogs to look under the building to see if anyone was trying to tunnel out of the place. At night we went to bed fully clothed under a single German army blanket.

We received two kinds of food in the camp: Red Cross parcels and German food—usually some kind of soup—cooked in the camp’s central kitchen. The Red Cross food came in corrugated boxes about one foot long and six inches high. The 10-pound parcels provided minimum nourishment for one man for one week; we each received about a third of a parcel a week.

All the Red Cross food could be eaten as is, or cooked, if heat was available. There were cans of good old Spam, beef stew, and something called “reconstituted butter,” along with cheese, powdered milk, dried fruit, crackers or cookies, and that all-time favorite, a quarter-pound bar of Hershey’s chocolate. The parcels also included small bars of Swan soap, useful for “spit baths” in our rooms and still more useful because of their wrappers—our only source of writing paper.

Thanks to the Salvation Army, we also received nourishment for our minds: the well-used library in our compound contained several hundred books that had been donated by people in the U.S. and Great Britain. Without them, there would have been nothing to read except an occasional German news-paper—impenetrable to most. The other main time filler was playing cards. A game called “Red Dog” was a favorite, and the POWs gambled with cigarettes provided in the Red Cross parcels.

Christmas at Stalag Luft IV was special. In Room 10, we melted down our chocolate bars and mixed them with crumbled graham crackers to make a sort of Christmas cake. We ate it while singing Christmas carols and thinking about our loved ones at home. It was a strange, ethereal moment when we all took a bite of our cake and realized, this was it. This was it for the Christmas of 1944. This was the opening of Christmas gifts at home. This was our Christmas turkey, goose, or ham dinner with family gathered round. This was the moment of thoughts of love for our moms, dads, sisters, brothers, and sweethearts. We all felt sure we would be with them the following Christmas, but we also knew that this bittersweet moment would live in our memories forever.

NEAR THE END OF JANUARY 1945, we began hearing artillery bursts from the east as the Soviet army pushed the Wehrmacht back into Germany. On January 30, word came that we would be evacuated the following day to another prison camp. The Germans always did their best to keep any of their POWs from being liberated; in the end, Hitler wanted to use us for bargaining power. Early the next morning, our guards issued each of us a full Red Cross food parcel. To the crunch of frozen snow under our feet, the entire complement of Lager B—about 1,800 men—marched out of Stalag Luft IV to the nearby railroad siding at Gross Tychow, where we climbed into rickety old boxcars.

A thin layer of straw covered the rough wooden floor of our boxcar, doing little to make us comfortable or warm. A five-gallon bucket served as our toilet. The Germans locked 25 of us in each narrow car. Then we all sat down with our backs against the sidewalls and our legs extended—our feet meeting in the center, sole to sole. To use the bucket we had to step over and between a floor full of legs and feet.

As uncomfortable as it was, I found out later we were the lucky ones: Lager B had been the only one to evacuate by train; more than 6,000 men from the other lagers were made to march 500 miles in one of Europe’s cruelest winters. It became known as the “Black March.”

Two days later, at dusk on February 2, our train pulled into the Berlin railroad marshalling yard and stopped. I don’t know why—possibly to rest the crew. We were all asleep when, at 10 p.m., the scream of air raid sirens jolted us awake. My heart pounded; I knew that in that railroad yard at night we were sitting ducks for the Royal Air Force. We heard the drone of aircraft and the explosion of many bombs, and shook in our boots awaiting a direct hit. With the acrid smell of smoke and dust in the air, the raid seemed to last forever. But after half an hour the bombs’ thunder stopped, the bombers quieted, and an “all-clear” siren sounded. Our train pulled out of the station at dawn the next morning.

One event on that trip is burned into my memory. After we passed through Berlin, one of the prisoners in the boxcar ahead of ours developed a fever and became quite ill. The one medic on the train had nothing to give him but aspirin. We heard he died that night with an aspirin still undissolved in his mouth. The following morning the train stopped in a peaceful countryside area, and the man was carried on a makeshift stretcher to the top of a grassy hill about 100 yards from the train track. Under a cold overcast sky, a half dozen of his buddies buried him while the rest of us watched through the cracks in the side of our boxcars. It was a very sad time for us, with a lot of frustration and anger.

After eight miserable days, our train arrived at the barbed-wire enclosed Stalag XIII-D, near Nuremberg, Germany, almost 300 miles southwest of Berlin. While we marched from the train toward the camp on a sunny, springlike February 8, we passed a column of about 500 American G.I.s, marching out. We shouted hellos, and they begged us for food and cigarettes. By talking back and forth as we passed each other, we learned they had been captured in what’s now known as the Battle of the Bulge—a battle we knew nothing about because we had no, or little, access to war news.

Stalag XIII-D was a camp for ground forces, rather than air forces, like our last. It had no recreation facilities, no library, and no athletic equipment. The airmen of the German Luftwaffe had superior facilities and pay compared to Wehrmacht soldiers; that difference was reflected in the treatment of their respective POWs. It mattered little though; the spring weather was delightful. And two months later, we were on the move again. With the sound of American artillery coming from the west, my group of about 500 men walked out of Stalag XIII-D on April 4 and headed for Stalag VII-A, 75 miles to the south. We marched during the day and spent the nights in barns our guards had commandeered along the way.

As I sat on a barn floor in a small town in west-central Germany one morning, eating a piece of hard brown bread, one of my buddies walked up to me and asked, “Hey Livingstone, you heard the latest rumor?”

“What now?”

“President Roosevelt died.”

“Oh sure, and we’re going to be liberated this afternoon.” It seemed too far-fetched to be true.

“I doubt that, but someone said a Jerry [German] guard told him the president died yesterday.”

We marched out that morning, in a drizzling rain. There was little talk among my fellow prisoners as we slogged along the muddy country road. We were all thinking about the president and our loved ones back

at home.

At noon my group came to a halt where the road curved around a low hill. I remember seeing the backs of two POWs as they trudged up the hill, through the knee-deep spring grass that made the Bavarian countryside so beautiful. One of them carried a bugle. The rain had stopped by then, but the sky was still slate-gray. The chilled air was heavy with the smell of damp earth and grass.

Finally the two men stopped and turned toward us. One of them, an officer, said in a voice loud enough for all to hear: “I have been told, and I have no reason to doubt, that President Roosevelt died yesterday, April 12. The sergeant will play taps now, and then we will have a few moments of silence.”

The sergeant raised his horn and played the saddest song I’ve ever heard. The sound was clear and pure, and I’m sure it could be heard for miles around that little hillock. I wasn’t the only one with tears running down my cheeks.

After the sergeant finished we all stood silently with our heads bowed, and I heard the unabashed weeping of a soldier somewhere among us. Then we marched on.

WHEN WE FINALLY ENTERED huge, forlorn-looking Stalag VII-A on a drizzly April 16 afternoon, we were tired and relieved. This would be the end of the marching, and we’d no longer spend nights in the small-town barns of Bavaria. At first glance the 85-acre camp didn’t look too bad, but upon closer inspection I could see the place was rundown and way overpopulated. My group unrolled our bedding in huge tents.

The camp—near Moosburg, about 30 miles northeast of Munich—had been originally established as a Polish POW camp for 10,000 prisoners. But as the war neared its end, the Germans moved more and more POWs from all over Germany there to prevent them from being liberated by the oncoming Allied armies. By some estimates, as many as 110,000 POWs, including 30,000 American soldiers, sailors, and airmen, were there. By the war’s end it was by far Germany’s largest prison camp.

Liberation came on April 29, 1945, when tanks of Combat Command A, 14th U.S. Armored Division entered the camp. We’d been hearing artillery for a week before and most guards had already departed, leaving just a skeleton crew behind, so we knew our life as prisoners was nearly over. POWs swarmed all over the first American tank to enter—but when a malnourished but determined-looking POW shimmied up the flagpole, tore down the Nazi swastika, and replaced it with the old Stars and Stripes, the camp really went nuts.

We weren’t going anywhere for a while, though. My diary entry for May 6 says, “Expect to be here all summer, ha. ha.” Finally, on May 8, we were up at 4 a.m., piled into the back of U.S. Army trucks, and rolled off toward Landshut, 10 miles to the northeast. About 10 miles beyond Landshut was a Luftwaffe base with a huge airport. For two and a half long hours, my group of 30 men waited, as thousands of American and British ex-POWs were shuttled out of Germany to Le Havre, France, in stalwart old C-47s. Finally our turn came. Bucking headwinds, the four-and-a-half-hour flight was the roughest I’d ever made—strictly white-knuckle time for all of us. After we landed at Le Havre, we learned that Germany had surrendered while we were in the air. What a great feeling. Now truly liberated, we were free at last.

Freedom is more than being able to leave home; it’s also being able to go home. ✯

THE PREQUEL

Bill Livingstone told the first part of his war story, “Worry Aboard Ole Worrybird,” in the October 2020 issue. It’s available online as “The Day a B-17 Gunner’s First Mission Became His Last.”

This article was published in the October 2021 issue of World War II.