The Gardner cartridge was expedient to manufacture, but proved fragile

The three-ring Minié ball is a Civil War icon, but in reality, the lead slugs came in many different forms. One of the most common Confederate-made varieties was the Gardner patent bullet, invented by Frederick J. Gardner of New Bern, N.C., who was issued Confederate Patent No. 12 on August 17, 1862, for the projectile with a thick bottom ring paired with another thin raised ring and two grooves. The bullet was unique in that it was not contained within a paper cartridge, but rather a gunpowder-filled paper tube was crimped to the base. As Gardner explained, that was to “expedite the manufacture…by superseding the necessity of tying the paper to the ball….”

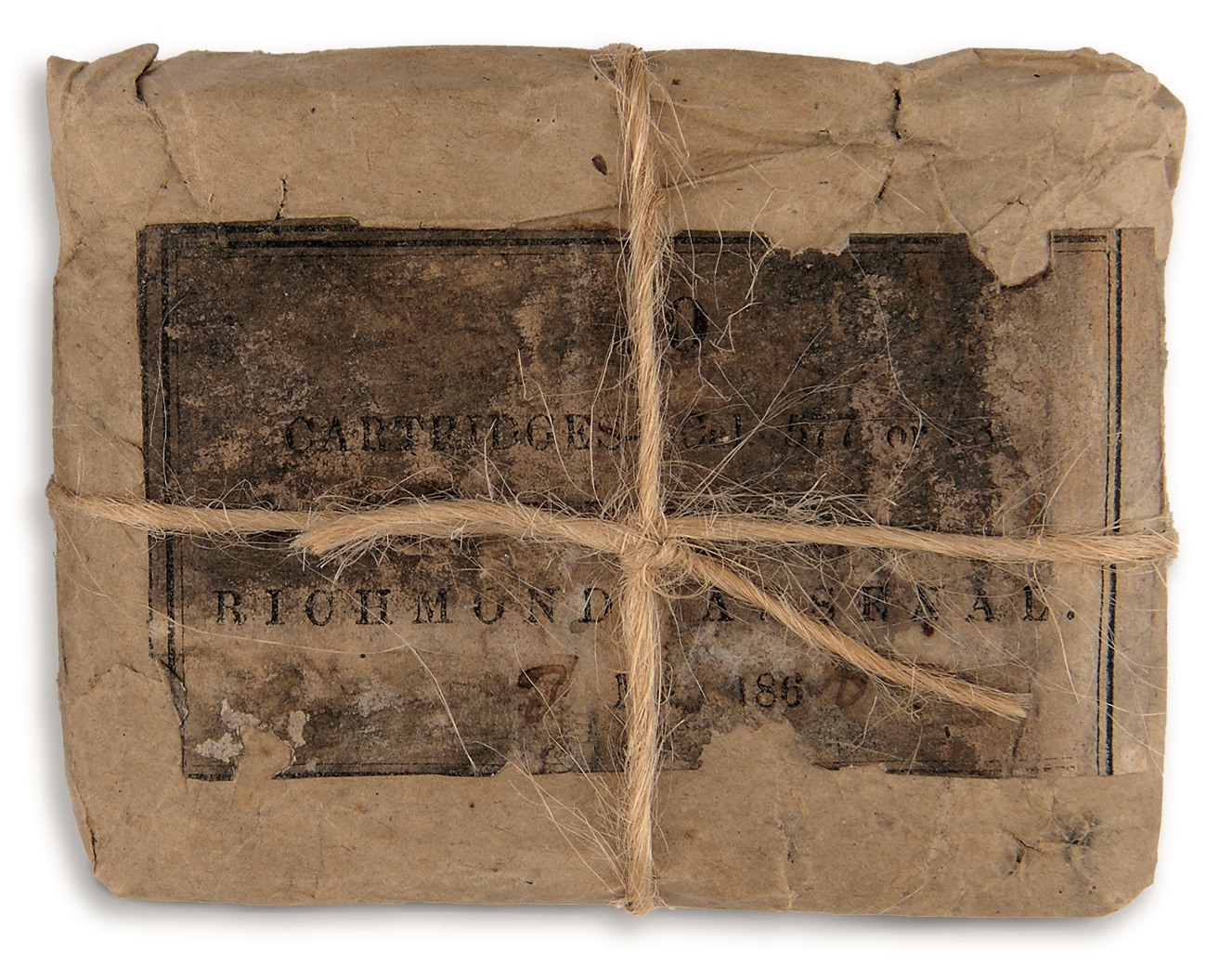

That concept did speed up the production of the cartridges, and initially Confederate Chief of Ordnance Brig. Gen. Josiah Gorgas and one of his subordinates, Lt. Col. John W. Mallet, were favorable of Gardner’s invention. Mallet considered it “ingenious in design and easily and rapidly made.” The Richmond Laboratory made most of the Gardner bullets, but they were also manufactured at the Confederate arsenals in Augusta, Ga., and Charleston, S.C. The Gardner cartridge became the most common round issued to Southern troops.

But unfortunately for the Confederacy, this Minié ball variant soon revealed major flaws. The paper cartridge often tore where it was crimped into the base during transport, wasting powder and rendering the round useless. Also, air bubbles could be introduced during casting that weakened the bullet. Gardners were also cast with very deep bases, compounding the problem and causing bullets to rupture upon firing.

Mallet complained to Gorgas in late 1863 that the “Gardner cartridge for small arms…is certainly the most inferior cartridge for the service….” “The only advantage of the machine is the rapidity with which it can be worked, but the labor of boys and girls for making cartridges by hand can be had in abundance,” he continued. Gorgas agreed with Mallet and in January 1864 production of the Gardner round ceased. The abundance, however, of archaeologically recovered Gardner bullets in the Eastern and Western Theaters, including many “blow throughs,” indicates their widespread use. —D.B.S.