Early in World War II the U.S. Army recognized its need for skilled linguists to interrogate captured enemy troops or conduct covert operations in Axis-controlled areas. Recruits included both Americans possessing German, Italian and Japanese language skills and immigrants who had fled Europe and Asia for the United States. Among them were the “Ritchie Boys,” some 15,200 men who attended the Military Intelligence Training Center at Camp Ritchie, Md. Many were German- and Austrian-born Jews who had fled Adolf Hitler’s genocidal Nazi regime—making them most determined enemies of the Third Reich. Military History recently spoke with Guy Stern, a “Ritchie Boy” and Bronze Star recipient. Stern, 98, is a former professor of German literature and cultural history at Wayne State University, which recently published his memoir, Invisible Ink. He remains director of the Holocaust Memorial Center in Farmington Hills, Mich.

Tell us about your early years.

My parents and generations of us were born in Germany. I grew up in a town called Hildesheim, near Hanover. I was the only one to get out of Germany. My entire family—my brother, my sister, my parents—all of them perished in the Holocaust.

Before that happened, my parents made an appeal to my mother’s brother, who lived in St. Louis. He said he could vouch for one person to get out of Germany, so I went to St. Louis. I graduated high school in 1939, but I could not afford college. I got a job and worked as a busboy for a year so I could enroll at St. Louis University. Then Pearl Harbor happened. There were recruiting posters all over town, and I saw one and thought, That is my war.

The poster was asking for anybody who had language skills in German to report to the Marine station in downtown St. Louis. The ensign there found that I had all the qualifications, but then he said, “I detect an accent.” He asked if I was born in the United States, and I said, “No.” He told me, “We can’t use you. We only take native Americans.” However, the draft happened a year later, and Army intelligence had no such qualms. After my basic training in Texas I was sent to Camp Ritchie.

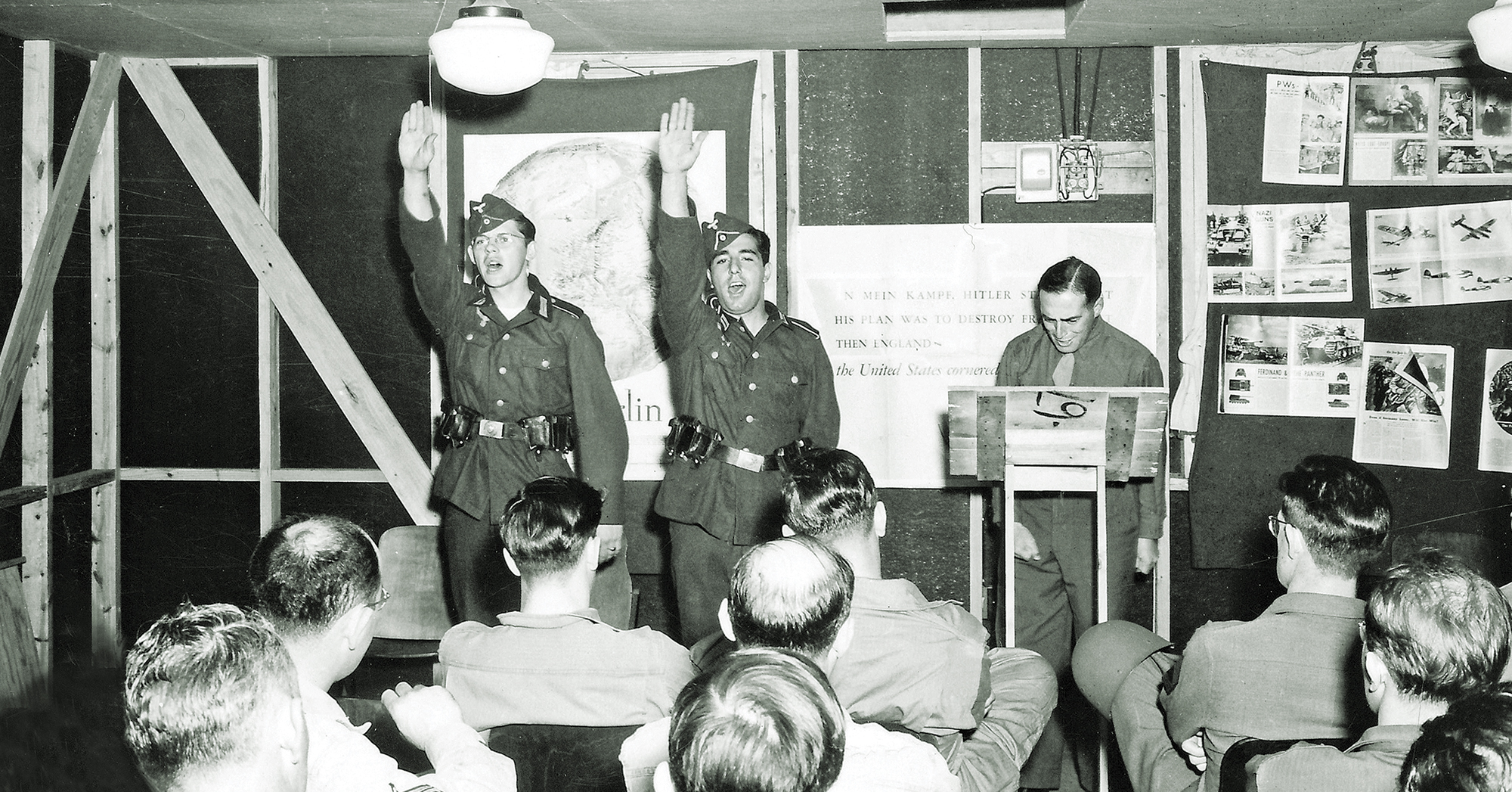

What sort of specialized training did you all undergo?

What sort of specialized training did you all undergo?

You had to remember a whole set of new knowledge. In [interrogations] the trick was finding common interest. For example, one time I was supposed to get information about industrial planning in the city of Düsseldorf. I told the POW, “Oh, I’m glad I get to talk to somebody from Düsseldorf. Your [soccer] team was at the top of the league midseason. What happened?” Because I was a football fan, he started talking.

You practiced on actual German POWs?

At first we interrogated each other, but then we got a contingent of POWs from the Afrika Korps [on which to practice]. They were briefed on what their fictitious past was, and they were instructed to be deceptive or clam up if the interrogator was clumsy. They became our guinea pigs.

[In learning to recognize enemy gear], memorization was key. We had a final exam where they spread 50 items of equipment, uniform parts and the like in front of us. We were given a clipboard numbered 1 through 50 and we had to enter in where each one went. I don’t think anyone got all of them. It was an impossible test [laughs].

Was Normandy your first time in combat?

Yes. It was my first real interrogation experience. After Normandy I joined what we called the survey section. The medics at that point wanted to know whether there were any [communicable] diseases spreading in the German army, because we were in contact with them. The engineers wanted to know how well the Germans had managed to repair their railways and their factories after we bombed them. We [in the survey section] got all that information.

We were also afraid of the Germans launching a desperate last stand using chemical weapons. So, as prisoners came off a truck, I immediately asked them, “How many of you are carrying gas masks and how many of you are wearing protective clothes?” My figures turned out to be entirely accurate. I concluded the Germans were not prepared [to launch a gas attack], because they were not defensive. That was when I got my decoration. And that’s my story on how I made the world safe for democracy—I did my job [laughs].

‘After Normandy I joined what we called the survey section. The medics at that point wanted to know whether there were any diseases spreading in the German army, because we were in contact with them. The engineers wanted to know how well the Germans had managed to repair their railways and their factories after we bombed them’

How is it you were chosen to interrogate war criminal Dr. Gustav Wilhelm Schuebbe?

It was actually my pal Fred Howard’s interrogation, and by happenstance we found out who [Schuebbe] was. Fred had a prisoner earlier that day [in April 1945] who was the nephew of Heinrich Himmler. The nephew carried a picture of his uncle in his wallet. Our MPs called our attention to it, and we took it. So that was circumstance one.

Second, it was the day [President Franklin] Roosevelt died. Fred had turned on his radio, because he wanted to find out how the Germans would react. Around midnight the German POW––a medical officer––comes into the tent and sees the photograph of Himmler hanging and hears the German propagandist radio station playing. He deceives himself he is at German headquarters. Fred was in civvies, and so the German says, “Oh, I am among friends.” We asked what he meant, and he said, “Well, you must have heard of me in this report. I am Dr. Schuebbe. I’m with the euthanasia program.” Fred’s interrogation partner got a slip of paper and wrote: Opium. The guy was an addict. The confession, so to speak, was involuntary.

But then two mistakes happened. Number one: Fred gave him a cup of coffee, which woke him up. Second, I made a mistake. One method of interrogation, which we rarely used, was fear. And what were the Germans most afraid of? Being in Russian captivity. So sometimes I would pretend to be a Russian liaison officer who spoke German with a Russian accent.

That night I walked in dressed as a Soviet commissar. [Schuebbe] looked at the “Russian” and clammed up. However, by then we had enough of a lead that by the following day we could unmask the truth that he was responsible for thousands of “mercy” deaths.

Were there any light moments in your work?

One day my captain called me and this other guy in and said, “I have something funny to show you.” It was a Canadian publication that made fun of us as interrogators. They created a fake report in German describing the effect of a bombing attack on a town and wrote that headless people were running around the market. It was a straight translation from German, but in English it means people who have lost their minds, not their heads.

Our captain said, “Why don’t you do something similar?” We ended up writing all sorts of things. For example, we wrote that Hitler had a shriveled scrotum. We made a big story out of it. That was our contribution to Army humor. We attached it to all the reports we made that day.

Years later my wife sees me rolling on the floor next to a book, laughing. It turns out two British military history scholars had found our reports with our notes on Hitler in the National Archives. They had fallen for it. It was an actual footnote in their book.

Would you say the “Ritchie Boys” were more motivated than most?

Yes. This was our war. Many of us were Jewish refugees, so we worked harder than anyone could have driven us. MH