For the Rebels, Cabin Creek proved too little, too late. But the victory was fun while it lasted.

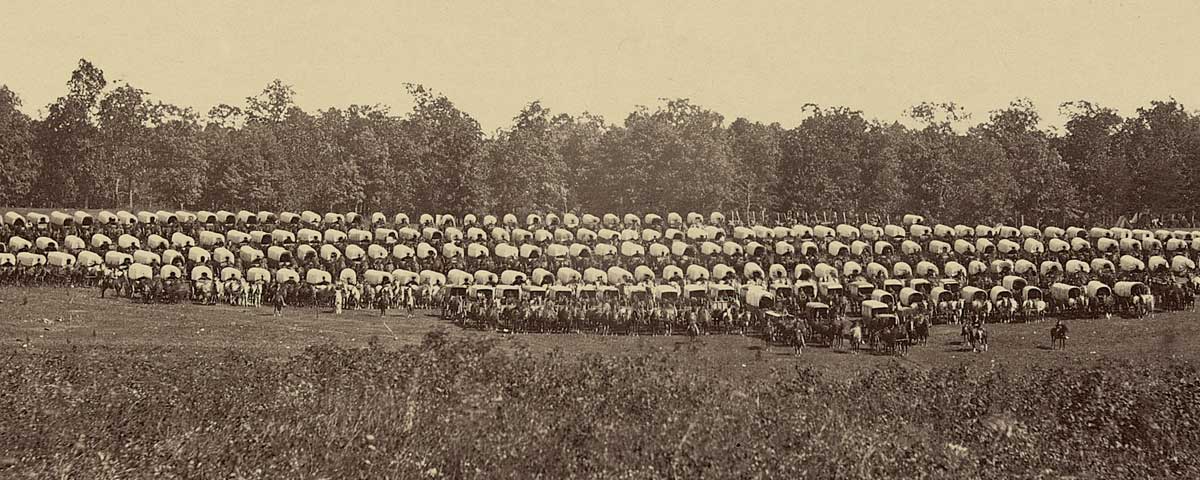

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n a bright moonlit night, Confederate Brig. Gen. Richard M. Gano, a former physician and respected Indian fighter from Grapevine, Texas, advanced his troopers toward the Union post of Cabin Creek in northeastern Indian Territory. Under the moon’s glare, they could see hundreds of covered wagons. Captain Patrick Cosgrove, commander of the Union pickets, noticed a line of dim shapes approaching. After one of his pickets fired a warning shot, Cosgrove, in a distinctly Irish brogue, barked out a command to halt.

A rattled Gano replied, “What are your men?”

“Federals,” Cosgrove answered. “And you?”

“Rebels, by God!”

Cosgrove defiantly hurled back, “May God damn you, sir! I invite you to come forward.”

Hoping for a negotiated surrender, Gano withheld acceptance of the invitation, saying “Will you protect a flag of truce?”

“I will tell you in five minutes.”

After a 15-minute wait, Cosgrove still hadn’t replied. Gano answered for him. He ordered the attack.

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]efore the Civil War, Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) was considered mostly a “dumping” ground for many of the country’s Native American tribes. The U.S. government forcibly removed the Cherokees, Choctaws, Chickasaws, Seminoles, and Creeks (known by whites as the “Five Civilized Tribes”) to the territory between 1830 and 1835. Internal differences among the tribes led to a bitter divide between pro-removal, pro-slavery factions that supported the Confederacy, and anti-removal, conservative factions that supported the Union. Despite attempts to keep Indian Territory peaceful, those smoldering differences became tribal firestorms during the Civil War. Both Union Indians, called “Pins” for the cross-pin insignias on their coat lapels, and Confederate Indians burned farms, butchered livestock, and forced thousands into refugee camps in Kansas and Texas. Indian Territory became a charred wasteland.

By the end of 1863, Federal forces held the northeastern portion of the territory, including all of the Cherokee Nation. Lacking manpower and local farms to forage from, they used fortified posts to secure their gains. Forts, however, were vulnerable to severed supply lines. Fort Gibson, an old U.S. Army post on the Arkansas River in what is now east-central Oklahoma, was the key to holding the northern Indian Territory. The Old Texas Road, between Fort Scott in eastern Kansas and Fort Gibson, was its vital supply artery, with the mule-driven supply wagons traversing it very tempting targets.

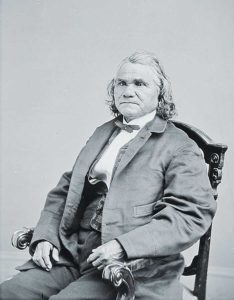

The Trans-Mississippi Confederacy relied heavily on hit-and-run cavalry raids, an ideal tactic for its outnumbered, supply-strapped forces. Few performed this ploy better than Confederate Brig. Gen. Stand Watie, a short, bowlegged Cherokee with a knack for guerrilla fighting. In September 1864, he received intelligence about a massive Union wagon train heading toward Fort Gibson. With Confederate command approval, a combined 2,000-man cavalry force of Texans, under General Gano, and Confederate Indians, under Watie, headed north from Camp Pike, near Fort Smith in Arkansas, to intercept it. Because of his seniority, Gano had overall command.

Sent ahead, scouts encountered a haying operation of 125 laborers at Flat Rock, just 12 miles northwest of Fort Gibson. Using horse-drawn mowers, members of the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry cut the hay, while a detachment of the 2nd Kansas Cavalry kept watch. On September 16, Gano’s troopers surrounded the haying operation, then attacked. “I dismounted my men and placed them in a ravine, which was no sooner accomplished than the main body of the enemy appeared and attacked me from 5 different points,” recalled Union Captain Edgar A. Barker.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”right”]“The sun witnessed our complete success, and its lingering rays rested upon a field of blood. Seventy-three Federals, mostly negroes, lay dead upon the field.” – Brig. Gen. Richard M. Gano[/quote]

Fifteen members of the 2nd Kansas managed to fight their way out. The rest were killed or captured. Based on Union reports and the considerable number of dead, some African-American soldiers were likely killed as they surrendered.

“The sun witnessed our complete success, and its lingering rays rested upon a field of blood,” Gano wrote. “Seventy-three Federals, mostly negroes, lay dead upon the field.” Confederate casualties numbered three. With time pressing to find that wagon train, Gano dispatched a released prisoner toward Fort Gibson to inform them of what happened. He would let the Federals bury their own dead.

After destroying the haying equipment, Gano continued north along the Texas Road and finally discovered the wagon train parked at Cabin Creek. His ragged men had never seen such a bonanza. Though a wooden stockade and a high bluff in the rear provided protection for the soldiers, there was not the same degree of protection for the wagon train. Most of them were parked haphazardly outside the stockade, guarded by no firm line of troops. The wagon train’s commander, Major Henry M. Hopkins, held little regard for warnings of local Confederate activity. Alfred Collins, a teamster, later remarked: “The train was allowed to camp in open order, scattered all over creation. It seemed like as though there wasn’t an enemy within one hundred miles of us.” To make matters worse, the Federals had no artillery. The Confederates did.

Early on September 19, Gano assembled his line of attack half a mile from the Union position, which was manned by about 330 Kansas and Union Cherokee cavalry. He placed the six guns of Captain Sylvanus Howell’s Texas Battery in the center. The 30th Texas Cavalry, meanwhile, was positioned to the battery’s left, and the 31st and 29th Texas Cavalry were placed to its right. Watie’s Indian Brigade, of Creeks and Cherokees, lined up on the right of the 29th, which, interestingly, was commanded by Colonel Charles DeMorse. A noted newspaper publisher from north Texas, DeMorse hated fighting alongside Indians, especially with Indian officers like Watie who outranked him.

Armed mostly with shotguns and outdated muskets, the Confederate line advanced north before encountering Cosgrove’s pickets.

The First Battle of Cabin Creek

In July 1863, Confederate Colonel Stand Watie (right) first attempted the capture of a Union wagon train en route to Fort Gibson. The results, however, were much different. Watie and about 1,600 men were ordered to Cabin Creek to intercept a wagon train heading out of Baxter Springs, Kansas. He took a position along the opposite side of a Cabin Creek ford and waited in ambush. The wagons were closely guarded by detached troops under the command of Colonel James Monroe Williams. Among his troops was the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry, the Union’s first African-American regiment. Hoping to prevent Williams’ crossing, Watie suffered through a sustained artillery barrage followed by an infantry attack. His men held off the attack until the Union troops withdrew across the creek. The Union troops launched a second attack with cavalry and this time, Watie was routed from the field. The urgent need for supplies at Fort Gibson prevented Williams from pursuing Watie further. Confederate casualties numbered 65 while Williams’ loses were 53 killed and wounded. The wagon train reached Fort Gibson safely and the supplies helped keep the fort in Union hands until the end of the war.

While they waited for Cosgrove’s reply, they could hear drunken taunts coming from the Union lines. Many of the Federals had helped themselves to buckets of whiskey inside the stockade. One drunken teamster approached the Rebel line “heaping vile epithets and curses.” Warnings from Gano’s men only increased the drunk’s resolve; he was shot dead. The opposing Cherokees taunted each other with the ancient turkey gobble call—a challenge no Cherokee warrior could ignore. At 1 a.m., the Confederate attack began in earnest with an artillery barrage of solid shot and shell. Wagons were set on fire while mules, troops, and teamsters ran about in panic.

As teamster Robert Morris Peck later wrote:

“Soldiers, teamsters, mules and wagons, in a perfect cyclone of excitement, went flying towards the timber [nearby woods]. Some men mounted and unhitched mules, where they could catch them, often only to be thrown off by the frantic animal. Some teams and parts of teams dragging their wagons, without guidance crashed into each other as they turned from rebel gunfire. There seemed to be no effort on the part of Hopkins and his officers so far as I could judge, to form the soldiers for a defense of the camp. I could see soldiers, teamsters and others striking out for the timber, on a track back to Ft. Scott. I started out afoot when a soldier’s horse, bridled and saddled but without rider came galloping past. I lunged out and quickly climbed into the saddle.”

FIGHT FACTS

2ND cabin creek Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory

September 19, 1864

Campaign

Confederate cavalry raid to capture Union wagon train bound for Fort Gibson, Indian Territory

COMMANDERS

Confederate:

Brig. Gen. Richard M. Gano (overall commander)

Brig. Gen. Stand Watie

Union:

Major Henry M. Hopkins

Numbers

Confederate: 2,000 cavalry and artilleryman

Union: Approx. 600 infantry, cavalry, and teamsters

FORCES ENGAGED

Confederate: Gano’s Texas Brigade Watie’s Indian Brigade Howell’s Texas Artillery Battery

Union: Detachments from 6th Kansas Cavalry 14th Kansas Cavalry 2nd Kansas Cavalry 1st Indian Home Guard 2nd Indian Home Guard 3rd Indian Home Guard

ESTIMATED CASUALTIES

Confederate 9 killed, 38 wounded (Watie’s wounded N/A)

Union 20 killed, 26 captured,

wounded not reported

OUTCOME

Confederate Victory

Twelve Union cavalrymen, under Captain Henry Ledger of the 6th Kansas, charged the Rebel battery. Ledger fell 15 feet from a cannon muzzle—his horse was riddled with canister shot, but he miraculously survived. Hopkins, meanwhile, had galloped off in a vain attempt to find reinforcements, but by 9 a.m., a white flag appeared over the stockade, the battle over. Gano’s men, sorely lacking in food, ammunition, uniforms, and shoes, were suddenly blessed with an overwhelming bounty. Of 300 Union wagons, valued at a whopping $1.5 million, the Confederates had salvaged 130, along with 740 mules. Twenty Union soldiers were killed, 26 surrendered, and an unreported number wounded. The Rebels lost nine killed and 38 wounded.

Within two hours, the captured wagons were assembled for the return home. Gano moved southwesterly along backroads to avoid Union troops marching from Fort Smith. At Pryor Creek, Federal troops under Colonel J.M. Williams caught up with the wagon train. An artillery duel ensued until nightfall. Employing a clever ruse, a Rebel detachment continuously drove a single wagon over rocky ground to sound like the captured wagons were being parked for the night. While the ruse was in play, Gano kept moving west and outdistanced Williams’ troops. When the Federals awoke the next morning, the Rebels were long gone. Having marched more than 80 miles, the Union troops were too exhausted to continue the chase. Instead, they fell back to reinforce Fort Gibson. Gano and the wagons had escaped.

Congratulatory messages were sent out by the Confederate-controlled Indian Territory’s commander, Maj. Gen. Samuel Bell Maxey. The Confederate Congress issued a vote of thanks. The raid’s greatest impact was on the Confederate Indians. A rush of confidence surged over the troops after months of neglect. From her home in North Texas, Stand Watie’s wife wrote her husband, “I thought I would send you some clothes, but I hear you have done better.” The morale boost would last only until the following spring. In June 1865, Watie surrendered—the war’s last Confederate general to do so.

Donald L. Barnhart Jr., a volunteer historian with the Texas Civil War Museum in Fort Worth, resides in The Colony, Texas.

Must Have Hurt

Richard M. Gano’s uniform coat survives and is on display at the Texas Civil War Museum in Fort Worth. The coat, with its braided sleeve markings denoting Gano’s official rank of colonel, is rent by a large, jagged hole at the left shoulder. Some sources indicate that Gano was shot at Cabin Creek, but Gano aide James R. Wilmeth stated that the wound was suffered April 14, 1864, at a skirmish east of Poison Spring, Ark. The only discrepancy in Wilmeth’s account is his contention that Gano was hit in the left elbow, not shoulder. Gano, who was born in Kentucky, and trained as a physician, moved to Texas in 1859. In 1861, he was elected captain of the Grapevine Volunteers cavalry, which fought at Gallatin, Perryville, and Chickamauga. He left active service because of illness, but returned and was promoted unofficially to brigadier general. After several fights in Arkansas in 1864, his Texas Cavalry command moved into Indian Territory and captured the Union wagon train at Cabin Creek. In January 1865, he was recommended for major general, but the war ended before it was approved.