For its first 60 years, the Pledge of Allegiance was a nonsectarian American vow, conceived to foster love of country in youths and among immigrants, and to heal the nation’s wounds in the wake of a vicious civil war. But in 1953, another conflict—the Cold War between democracy and communism—was on, and Congress decided the deity had a place in the pledge.

Following the War Between the States, the Union flag emerged as a popular American symbol. Admirers undertook to establish an official Flag Day. Many school systems embraced the concept, but decades would pass before the event achieved national holiday status. Nonetheless, by the 1880s affection for the Stars and Stripes had grown so enthusiastic as to interest The Youth’s Companion. The Boston-based weekly, in business since 1827, had 475,000 readers; subscribers paid $1.75 a year and anyone who signed up received a premium. To honor the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s discovery of America, publisher and editor Daniel Ford decided to hand out tricolors with subscriptions. That campaign had been under way for two years in 1890 when Ford heard minister Francis Bellamy preach at Bethany Baptist Church in Boston. The temperance advocate impressed Ford with his elucidation of Christian Socialist theology, which looked warily on capitalism and expressed sympathy for the workingman. Bellamy’s views drew on the philosophy of his novelist cousin, Edward, famous for the utopian ideas in his futuristic 1888 best seller, Looking Backward.

In 1891, Francis Bellamy quit Bethany Baptist over money. Ford hired him for The Youth’s Companion Columbus quadricentennial project. As part of the increasingly prominent promotion, James Upham, Ford’s nephew, was struggling to compose a pledge to the flag.

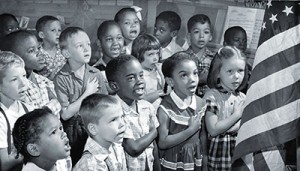

That July, President Benjamin Harrison issued a proclamation to honor Columbus Day with ceremonies in schools and other places of assembly. “The system of universal education is in our age the most prominent and salutary feature of the spirit of enlightenment, and it is peculiarly appropriate that the schools be made by the people the center of the day’s demonstration,” Harrison said. “Let the national flag float over every schoolhouse in the country, and the exercises of such as shall impress upon our youth the patriotic duties of American citizenship.” In February 1892, the National Education Association, which then as now represented teachers, endorsed the flag project and named Bellamy chairman of an NEA committee on the Columbus celebration.

At the time, the best-known—and perhaps only—verbal salute to the flag had been composed by Colonel George Balch, principal of a free kindergarten in New York City for poor and immigrant children. “We give our heads and our hearts to God and our country; one country, one language, one flag,” Balch had written.

Upham asked Bellamy if he could do better.

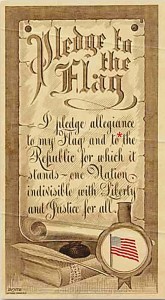

In August 1892, the minister finished writing: “I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” Upham approved and suggested an accompanying gesture: coming to attention, snapping together the heels upon beginning the recitation, and, while speaking, extending the right arm, hand palm up. Ford and the NEA approved the pledge and the salute, featured in the September 8, 1892, Youth’s Companion. Bellamy had wanted a writing credit; Ford said no, citing the magazine’s policy of anonymity for contributors. More than half of the country’s 120,000 public schools participated in the October 1892 National Public School Celebration.

In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson issued an official proclamation establishing June 14 as Flag Day but not making the holiday official. In 1923, to standardize flag etiquette and help immigrants assimilate, the American armed forces and nearly 70 other entities convened a National Flag Conference. Among other guidance, the Flag Code stipulated that flags too worn or damaged to be suitable for display were to be disposed of in a dignified way, preferably by burning. To encourage immigrants to understand the difference between their homelands and their adoptive country, organizers revised the pledge from “I pledge allegiance to my flag…” to “I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States.” The words “of America” were added in 1924.

The government revisited the pledge on June 22, 1942, when President Franklin Roosevelt signed a joint congressional resolution incorporating the pledge into the 1923 code. And because the Nazi “Sieg heil!” salute bore a creepily close resemblance to the Youth’s Companion gesture, that December FDR signed another resolution: Instead of raising their right arms, civilians reciting the pledge were to hold their right hands over their hearts; active duty military personnel would salute.

On August 3, 1949, President Harry Truman made Flag Day a national holiday. Less than a year later GIs were fighting in Korea. The Soviet Union and China had emerged as foes. Senator Joseph McCarthy, R-Wisconsin, was warning of a Red-riddled government. The times encouraged talk of inserting the language of faith into the Pledge of Allegiance. In April 1951, members of the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic men’s organization, began to include “under God” after “one nation” when reciting the pledge. The Knights urged Congress to institute that change nationally. Sentiment for the new wording grew after the 1952 election saw World War II hero Dwight D. Eisenhower win the White House by a landslide and the House and Senate go Republican.

Affirmation of a national relationship with a higher being seemed to be in order. The spirit was bipartisan; in early 1953, Democratic Representative Louis C. Rabaut of Michigan sponsored a resolution to incorporate the words “under God” into the pledge.

Debate was fraught over the phrase’s meaning. Congressional leaders, especially Republicans, were feeling pressure from conservative sects to invoke Jesus Christ and Christianity by name. Senator William Langer, a North Dakota Republican, decided to have the judiciary subcommittee he chaired hold hearings on a constitutional amendment recognizing the authority and law of Jesus. Others on Capitol Hill offered reassurances that rewording the pledge was not an attempt at establishing a state religion. One was Rep. Charles G. Oakman, a Republican from Michigan and sponsor of one of the 17 “under God” bills introduced.

“The phrase ‘under God’ is all-inclusive for all religions and has no reference whatever to the establishment of a state church,” Oakman said. “One can pledge allegiance to a flag symbolizing a state founded upon a belief in God and, at the same time, accept the doctrine of a separate church and state. A distinction exists between the church as an institution and a belief in the sovereignty of God.” As for atheists, Oakman said, “there is a vast difference in making a positive affirmation on the existence of God in whom one does not believe, and on the other hand making a pledge of allegiance and loyalty to the flag of a country which in its underlying philosophy recognizes the existence of God.”

No serious opposition materialized, but concerns about separation of church and state crossed party lines and crept into the official record. After President Eisenhower signed the pledge changes into law, Republican Representative William E. Miller of New York noted clerical fears. On June 22, 1954, Miller quoted the Rev. George N. Marshall, a Unitarian minister who saw the change in the Pledge of Allegiance, along with an amendment seeking to put Jesus in the Constitution and a California proposal requiring loyalty oaths for churches, as signs of a dangerous erosion of the separation of between church and state.

Signing House Joint Resolution 243 on Flag Day 1954, Eisenhower invoked his country’s need for reassurance in parlous times. “Over the globe, mankind has been cruelly torn by violence and brutality and, by the millions, deadened in mind and soul by a materialistic philosophy of life. Man everywhere is appalled by the prospect of atomic war,” the president said. “In this somber setting, this law and its effects today have profound meaning. In this way we are reaffirming the transcendence of religious faith in America’s heritage and future; in this way we shall constantly strengthen those spiritual weapons which forever will be our country’s most powerful resource, in peace or in war.” ✯

This story was originally published in the September/October 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.