Two homes, very small by modern standards, have become icons of the Battle of Gettysburg. The stone Widow Mary Thompson house stands just north of the Chambersburg Pike at the west end of town, and is famed as the headquarters of Army of Northern Virginia commander General Robert E. Lee. Southeast of Gettysburg, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade used the simple frame home of Lydia Leister, just west of the Taneytown Road, while he led the Army of the Potomac. While the homes served as nerve centers for their respective armies, there is more to the story. Both were owned by widows who had struggled with alcoholic husbands and societal expectations that deemed them to be subservient to men. The 1848 Women’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, N.Y., spurred some urban women to break out of traditional female roles to engage in politics and reform movements. In small rural towns like Gettysburg, however, things moved more slowly. The lives of Widows Leister and Thompson changed dramatically not from any declaration but from the war’s uncaring havoc.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap] visitor to Leister’s farm in 1863 described her as having a German face and a strong German accent. She was born in Allegheny County, Md., in 1811, one of the seven children of Dr. John Study and his wife Hannah. Typical for the time, her brothers were educated—two of them were also physicians—while she and her sisters were not, and Lydia was described as illiterate. She married James Leister sometime before 1830 and together they resided in Silver Run, Md., 15 miles southeast of Gettysburg, in a house built for them by James’ father. James and his brother were also given a textile mill by their father.

The future should have been bright and James should have had a steady income, but according to family genealogy, the sons “liked their corn makings,” or drank too much, causing their father to resume ownership. By 1850, James and Lydia and their first two children moved to Greenmount, Pa., several miles south of Gettysburg along the Emmitsburg Road. Lydia’s sister, Catherine Slyder, lived just up the road in the shadow of Big Round Top, and her brother, Dr. David Study, also lived in Gettysburg.

The Leisters had four more children before James, still drinking and in poor health, died of consumption in December 1859. Lydia lost no time in putting her financial affairs in order. She had been given a sum of money upon her father’s death that was to be held in trust for her until James died. That wise proscription indicates her father was well aware of James’ drinking habits and wished to protect Lydia’s inheritance, as women could not own property at that time.

A month after James’ death, the new widow sold her late husband’s carpenter tools, lumber, and some household furnishings. The proceeds, combined with the money from her father, allowed her to purchase the nine-acre property at the southern base of Cemetery Hill from Henry Bishop for $900 (about $24,400 today) in March 1861.

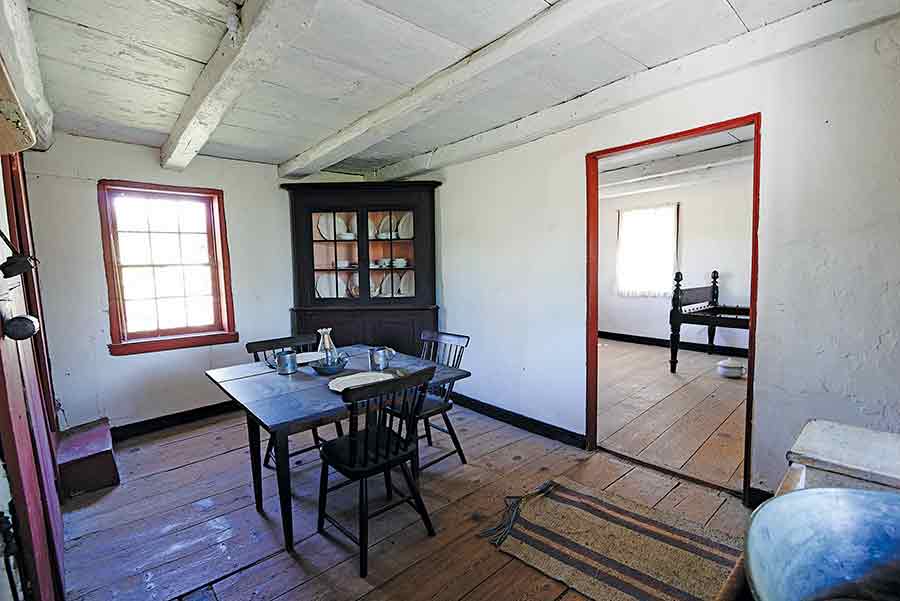

The subsistence farm’s output was enough to support herself and her family of four, as her two oldest daughters had married and moved away. The humble 1½-story wood farmhouse, built around 1840, had two rooms on the main floor, a sleeping loft above, and a front porch. The farmstead had a log barn and several small outbuildings, an orchard, a pasture, and several tillable fields. A spring burbled out of the southeast corner of her land.

Lydia fenced off a small but substantial garden, put up sturdy fences to protect her fields planted with wheat and oats, and pastured a cow and a horse. By early 1863, she owed just a small amount on her farm, so she planted an extra field of wheat to sell and raise the additional funds.

And by then, her house was a bit less crowded. Her oldest son, Amos, had enlisted in the 165th Pennsylvania Infantry the previous October. Youngest son Daniel was living with and working for another family, a common arrangement in that era. As the heat of summer began to rise, Lydia and her two youngest daughters, 10-year old Hanna (called “Mary”) and 7-year old Matilda (called “Anna”) went about their routines on the farm. Through her own hard work, and the protection of her father, Lydia had overcome numerous setbacks to gain her the quiet life she enjoyed.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he stone house of Widow Mary Thompson was built north and west of town, on the Chambersburg Pike. Mary (Long) Thompson was born in 1793 in modern Adams County, Pa. In 1818, Mary married Daniel Sell and moved with him to Maryland. The couple had two daughters, Eliza and Hannah, and were expecting their third when Daniel died at the age of 30 in 1822. Upon her husband’s death, the young widow moved back to Pennsylvania and gave birth to her third daughter, Mary Jane. Several years later, Mary married Joshua F. Thompson, and by 1830 the couple moved to a farm along the Hunterstown Road. Here the last five of her eight children were born—James Henry, Elias, Catherine, Margaret, and Susannah.

Joshua farmed and worked as a wood chopper, but he also drank excessively and abandoned his family. By 1836, Mary’s circumstances were becoming tenuous, and her three youngest children appeared on the list of “Poor Children” in their Adams County community northwest of Gettysburg. Two years later, she inherited $250 from her father’s estate. Not surprisingly, Joshua reappeared after that for a brief time. But by 1838, he had disappeared again, this time for good. A court hearing in late 1841 deemed him a habitual, longstanding drunkard, unable to manage his own affairs. For that reason, Mary petitioned the court to have a guardian appointed for her four youngest children, all under age 14. Her son James, who was already 14, made his own petition. David Ziegler was appointed as guardian for all five children.

Around this time, Mary and her family were still living outside of Gettysburg. Several years later, however, she moved her family to the stone house on Seminary Ridge that would make her part of the Gettysburg battle story. The house had been built about 1833 and was owned by Michael Clarkson in partnership with David Ziegler and others.

Clarkson auctioned the house and four acres in 1846, and they were purchased by former Gettysburg attorney and Pennsylvania legislator Thaddeus Stevens, who then held the property in a trust for Mary Thompson. In his history of Thompson’s house, The Story of Lee’s Headquarters, author Tim Smith explains that the relationship between Stevens and Mary remains unclear, but speculates that Stevens may have bought the home for her because she could not own property as a married woman, and the arrangement would protect her if her husband reappeared. By 1850, however, she learned that Joshua had died the previous year. During the decade before the war, the Widow Thompson took a position as a steward at the Lutheran Theological Seminary, just across the road from her home.

As the third summer of the Civil War approached, all of Mary’s children had moved out, although James resided across the street and Hannah lived a few doors to the east along the Chambersburg Pike.

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]ith the suddenness of a bolt of lightning, the lives of both widows changed in the summer of 1863. In late June, Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s Division passed through Gettysburg. And on July 1, an unplanned encounter between two brigades of Union cavalry and a division of Confederate infantry erupted into battle west of the town.

As the fight escalated, Union soldiers urged town residents to leave. Leister reluctantly filled a basket with clothing for her daughters and prepared to head south. Before leaving, she grabbed a can of lard and hid it under a bench in her kitchen. Lydia staggered down the Taneytown Road, congested with fleeing civilians, Union troops, and supply wagons. A Union staff officer saw her plight and lifted Anna onto the saddle with him and led them to the George Spangler farm nestled between the Baltimore and Taneytown roads.

But fighting less than a mile to the west soon disrupted that apparent haven from the battle, and the Spangler farm’s fields and barn soon began filling with wounded and dying men of the Union’s 11th Corps. As chaos erupted all around them, Lydia and her children once again went looking for safer quarters. They were escorted to the Baltimore Pike, where sympathetic neighbors took them in.

While Leister and her children hunted for safety, Union staff officers commandeered her little house to serve as General Meade’s headquarters due to its location along the Taneytown Road behind the center of the newly developing Union line. Meade spent a great deal of time on the battlefield surveying and adjusting his troops, but the structure was a hub of activity for Federal officers.

Twelve generals jammed themselves into the tiny house on the evening of July 2 during Meade’s famous council of war that determined the Army of the Potomac would stay at Gettysburg. The Confederate artillery bombardment that preceded Pickett’s Charge on July 3 deluged the farmstead with iron. Men and horses were struck in the yard, and portions of the house were splintered. Conditions were so unsafe that Meade relocated his headquarters. Leister’s property was also used as a temporary aid station.

Mary Thompson, meanwhile, had remained in her house on Seminary Ridge as fighting grew ever closer to her front door. On July 1, as Union batteries posted along the road in front of her property boomed toward the oncoming Rebels, the railroad cut just north of her house filled with fighting soldiers from both sides. Union troops were driven off Seminary Ridge as the afternoon of July 1 waned, and Thompson’s house was behind Confederate lines as the day ended. She did what she could for the wounded and injured, and used up much of her bedding and pieces of her clothing for bandages. Some of her carpets were used to wrap the dead.

Confederate staff officer Walter Taylor ordered Sergeant Martin Gander, 39th Virginia Cavalry Battalion, to place four guards around the stone house about 5:30 p.m. on the evening of July 1, as it was to serve as part of General Lee’s headquarters. Gander recalled that while he was stationed at the house, he was given messages to deliver to Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell and Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson.

There has been recent controversy about whether the Thompson house had actually served as Lee’s headquarters. Part of Lee’s headquarters did consist of tents pitched directly across the road. But Smith lays out compelling evidence in his book that Lee spent time in the home to dine, rest, and meet with his commanders. From the first few days after the battle, it was accepted locally, and then later among veterans, that the Widow Thompson’s house was where Lee established a headquarters for a portion of his time in Gettysburg. Thompson later insisted in several interviews that she did not cook for General Lee and his staff. Several local residents were accused of disloyalty while the Confederates occupied Gettysburg in July 1863, and it is understandable that she would make that point to all who inquired about her experiences during the battle.

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]everal days after the armies vacated Gettysburg, Lydia Leister returned home. The garden had been trampled and its fence badly damaged. Her own horse and cow had disappeared, but 17 dead Union horses were scattered around her fields and near her spring, fouling the water and rendering it unusable. Several horse corpses had been burned near Lydia’s best peach tree, ruining it in the process. Other orchard trees were bent and broken, and the wheat that she had planted to help pay off her farm was destroyed. Leister’s barn siding had been removed for firewood and grave markers. Two tons of hay were gone.

The condition of her house was even more distressing. The porch pillars were shot away, and artillery projectiles had gouged holes in her roof and the east side of the farmhouse, and one round had entered the garret. Another had shattered a bedstead. Federal officers had dragged most of Lydia’s furniture outside in the yard. Bedding and some clothing were missing, and her food stores were used up. A shell had struck the bench under which she had hidden her can of lard, sending pegs and splinters into the lard.

Mary Thompson never vacated her house during the battle. Like Leister, her food stores were consumed and her linens and carpets were used to care for the wounded and dead. In an account published in 1864 by Professor Michael Jacobs, a Gettysburg resident who spoke with Thompson after the battle, she shared that Lee was of gentlemanly deportment but that Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s manner was rough and cruel. She also complained that some of Lee’s attendants stole and destroyed her property. Mary’s yard, orchard, and garden were trampled, her fences broken down, and several temporary graves of both Union and Confederate soldiers were nearby.

Sister in the Maelstrom

While the Widow Leister’s house gets generous visitor traffic, the home of her sister, Catherine, the Slyder Farm, sits on a quiet lane at the base of Big Round Top. On July 2, 1863, however, the stone house got plenty of unwanted visitors when the 47th and 15th Alabama of Brig. Gen. Evander Law’s Brigade swept over the Slyder’s 75-acre property during the flank attack of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s First Corps. The 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters hunkered down behind a stone fence on the Slyder Farm to delay the Alabamians’ advance, generating deadly gunfire that some combatants likened to a hornets’ nest. A sharpshooter’s monument erected on the ground here depicts a nest of those vicious stingers, below.

Had John and Catherine dared to look out their front door on July 2, they would have witnessed the horrific struggles for Devil’s Den and Little Round Top taking place to the northeast. One last bit of bloodshed occurred on the farm on July 3: Union Brig. Gen. Elon Farnsworth’s futile cavalry charge, cut short by Confederate gunfire that emptied saddles and killed Farnsworth.

Perhaps because of the devastation they had suffered, the Slyders put their farm up for sale in September 1863. “As I intend to move to the West, I will sell on very reasonable terms,” John proclaimed in a sale notice. The sale went through, and Lydia bade goodbye to her sister and her family as the Slyders moved to Ohio. –D.B.S.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he resilient women began to pick up the pieces. Leister heated up her lard and strained out the blasted wood bits, and then went on to rebuild her farm and its successful operation over the remaining years of her ownership. She never received compensation from the federal government for the damages she suffered as a result of the battle, but she found ways to survive. She turned the dead horse carcasses that poisoned her spring into money when she let them rot away and sold their bones, probably for fertilizer, for $375, an equivalent of about $6,000 today. More crops were planted and sold or used for barter to replace what she had lost. She had a new well dug.

By 1868, Lydia’s financial stability was such that she was able to nearly double the size of her farm by purchasing the fields, meadow, and orchard that adjoined her property to the north for $900. In 1874, Lydia built a two-story addition onto the east side of her house along the Taneytown Road.

In 1881, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association desired to place avenues along important landmarks on the battlefield, but most of the rights-of-way were on private property. A committee was tasked with proposing valuations for the various tracts, including Lydia’s. The right-of-way across her land for the proposed Meade Avenue was valued at $100 but was never offered as it was deemed too high. Instead, a court assessment reduced it to $21.87, though the latter offer was never acted upon.

The following spring, a Union soldier’s remains were found on Lydia’s farm and moved to the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. In 1887, the GBMA offered the aging widow $3,000 ($81,300 today) for Meade’s Headquarters. The transaction was completed by April 1888. The addition was removed and moved into downtown Gettysburg, and Lydia lived there until her death at age 84 in 1893. She was buried beside her long-dead husband in Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery.

The GBMA leased out the land and buildings at Meade’s Headquarters, a practice that the War Department continued during its 1893–1933 battlefield stewardship. When the National Park Service took over the battlefield in 1933, it discontinued using the property as a tenant farm and began to use it for interpretative exhibits. The house was fully restored in 1966 and today looks much as it did just before it endured the bombs of Pickett’s Charge.

The Widow Thompson continued to live in the stone house on Seminary Ridge until she died at age 79 in May 1873. She is buried under a modest stone in the historic section of Evergreen Cemetery. Her house remained part of the Thaddeus Stevens estate, after Stevens died in 1868. In 1888, the house was sold at auction for $740 to Philip Hennig of Gettysburg. It remained in private hands because the GBMA focused on preserving the Union battle lines and had little desire to acquire Confederate-held ground or landmarks. The War Department began to acquire Confederate battle lines in 1893, a monumental task requiring time and money, and the Thompson home was not considered a top priority.

Fire gutted the house in 1896, but the stone outer structure still stood. In 1921, the house was sold to Clyde Daley, who established the public Lee Museum, which dramatically changed the site’s 1863 appearance. Over the decades, it would remain a museum, although ownership changed a few more times. In 2015, the Civil War Trust purchased the site and restored the house and property as it was when the Widow Thompson lived there.

The two homes on the opposite ends of town share a great deal in common. They are both physically small, and both played important roles in the largest battle of the Civil War. Just as important, they both serve as a testament to two tough locals who succeeded through war and peace in a challenging era for women.

Sue Boardman is a licensed Gettysburg battlefield guide, the Leadership Program Associate Director for the Gettysburg Foundation, the co-author of The Gettysburg Cyclorama: The Turning Point of the Civil War on Canvas, and an avid photographer of avian raptors.