In late 1916 a German naval adventurer slipped the British blockade aboard a three-masted windjammer to raid like the pirates of old

The golden age of fighting sail lasted more than 300 years, from the reign of English King Henry VIII to the advent of steam-powered ironclads in the American Civil War.

But the stirring sight of a majestic cargo-carrying windjammer under clouds of canvas was not uncommon even as late as World War I. Sailing ships still crisscrossed the seven seas, carrying everything from sugar to timber to fish and dried coconut. The wooden- and iron-hulled vessels were slower than their steam-powered descendants, but they were also cheaper to operate and cost-effective on the secondary routes most steamship companies chose to ignore. As a result, at the outbreak of war in 1914 several of the belligerent nations still operated commercial sailing ships, which plied waters everywhere from the confined Baltic to the vast Pacific.

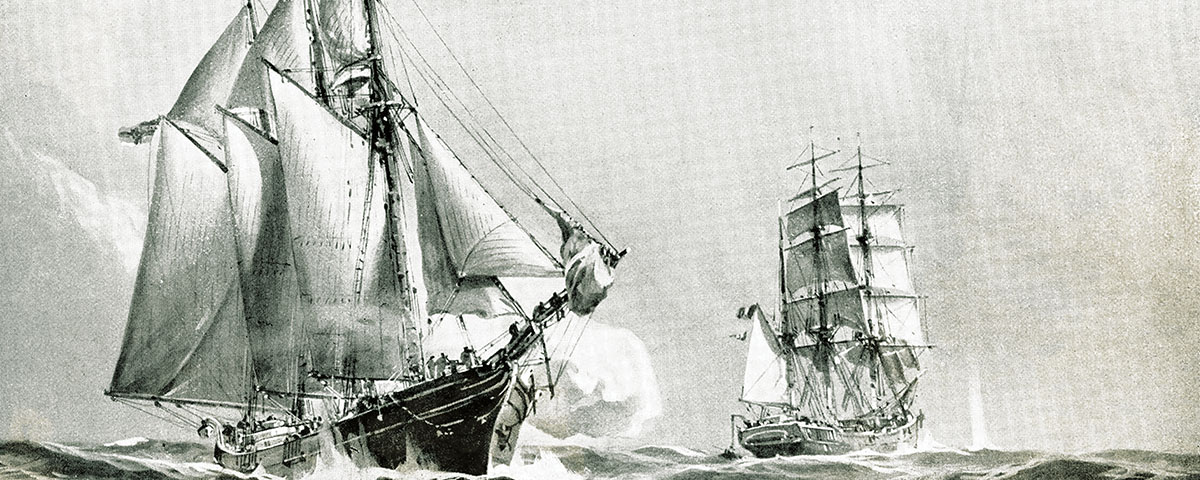

However, one of those ships was not what it seemed. By all appearances a harmless and dowdy wind-powered merchant vessel, it was in fact a deadly predator, a shark among minnows. Its name was SMS Seeadler, and it wrote the very last page in the saga of fighting sail.

By the autumn of 1916 World War I had been raging for more than two years, and for that entire period the British Royal Navy had blockaded Germany’s ports. Even as Kaiser Wilhelm II’s armies were driving hard to take Paris, his nation, heavily dependent on foreign wheat and fertilizer, was forced to live off its hump. With the mighty High Seas Fleet largely bottled up in Kiel and Wilhelmshaven, U-boats and commerce raiders conducted Germany’s only offensive naval operations. Submarines, yet to truly make their mark in naval warfare, were too few in number and limited in range and speed. But a few commerce raiders—armed liners and merchant ships—had managed to slip past the Royal Navy early in the war to prowl the vulnerable Allied shipping lanes.

In 1916 the German Imperial Admiralty, encouraged by the success of prior raiders and eager to put more into service, proposed that a large sailing ship, properly armed and disguised, might slip through the British blockade to raid the shipping lanes. As ludicrous as the idea may have sounded, it did have compelling advantages.

Most steam-powered oceangoing raiders were subject to one serious limitation: a shortage of coal. Germany had few colonies around the world and consequently almost no coaling stations. Thus German raiders had to either capture British colliers or have German ones meet them at sea. Any vessel that could remain at sea for long periods without refueling had an inherent advantage. Windjammers were the ultimate sailing ships. Far larger than the sleek clippers that preceded them, the huge square-rigged barks had three, four and even five masts from which to fly acres of canvas. Often built of iron and steel rather than wood, they could sail under the most difficult weather conditions. Moreover, the British were unlikely to suspect a large sailing ship of being a raider.

To captain such a vessel the Admiralty turned to Count Felix von Luckner, a powerfully built German aristocrat, naval officer and sailor since age 13. Other officers, incensed that the Admiralty would offer a mere lieutenant commander an independent command, sought to depth charge Luckner and sowed seeds of doubt about the entire venture. Summoned before the kaiser, the young officer spoke bluntly. “Your Majesty, if our Admiralty says it’s impossible and ridiculous, then I’m sure it can be done,” Luckner assured him. “For the British Admiralty will think it impossible also.”

Born in Dresden in 1881, Luckner ran away from home in 1894 to become a sailor, thus breaking a proud, three-generation family tradition of service as cavalry officers. Under the name Phelax Luedige he spent the next seven years sailing the world, in the process learning to speak English and Norwegian. At age 20, still using his alias, he returned to Germany and studied navigation, then joined the merchant marine as a petty officer aboard the small Hamburg South America liner Petrópolis. A year later he joined the German naval reserve under his real name and obtained a commission as a lieutenant. Luckner was called to active duty on Feb. 3, 1912, at a time when Germany and Great Britain were building giant dreadnoughts of ever-increasing power and speed.

The young naval officer saw combat action at Heligoland Bight in 1914 and Jutland in the spring of 1916. Then came the call from the Admiralty. Intrigued at the idea of converting an old square-rigger into an armed commerce raider, he threw himself into the project. It was just the kind of daring adventure Luckner could make into a success, given his years of experience aboard sailing ships. It also appealed to his sense of the dramatic.

The vessel that would enter German naval service as the merchant raider SMS Seeadler (Sea Eagle) had been launched in Scotland in 1888 as Pass of Balmaha, later sailed under an American flag and fell into German hands in a roundabout way. In 1915, while sailing from New York to Arkhangelsk, Russia, with a cargo of cotton, the ship had been intercepted in the North Sea by a Royal Navy cruiser. Though the United States was neutral at the time, the British captain had detained the bark on suspicion of carrying contraband and put a crew aboard to sail it to Scapa Flow for inspection. Over the objections of the American crew, the British had foolishly lowered the ship’s U.S. flag and flown their own naval ensign. Fate had then intervened in the form of a German U-boat, whose suspicious captain seized the bark and sent it to the North Sea port of Cuxhaven. From there Pass of Balmaha had sailed up the Elbe River to Hamburg. The Germans had released the U.S. crewmen but imprisoned the British prize crew.

At 4,500 tons and just over 250 feet, the windjammer was large enough for the job the Germans planned for it. It would operate undercover as a Norwegian cargo ship, ostensibly transporting lumber to Australia. The vessel underwent extensive conversions, beginning with the installation of a 950-hp auxiliary diesel engine and propeller shaft fitted just ahead of the rudder, to provide propulsion when becalmed or in slack winds. Its instruments and gear were worn, weather-beaten and Norwegian-made. False stacks of lumber on the port and starboard bows concealed two 105 mm SK L/45 naval guns.

As Luckner put it, Pass of Balmaha became “a mystery ship of trick panels and trick doors.” In addition to quarters for 64 officers and men, it could carry up to 400 prisoners—the passengers and crews of ships Luckner captured. The “cells” were carefully constructed to be invisible to enemy boarding parties, cunningly hidden behind false panels in the hold, which appeared filled with stacks of crates and cargo. Luckner was adamant the prisoner quarters have ample bunks, a separate mess, even games and reading material. “I wanted them to feel as though they were my guests,” he later said. It was more than gentlemanly chivalry, of course. If well cared for his “guests” would be more likely to behave and not sound the alarm when Seeadler was approaching another victim.

To crew the raider Luckner chose German navy volunteers with experience aboard sailing ships. Like their captain, several spoke Norwegian, some fluently. One young man, a slender, smooth-cheeked mechanics’ helper named Schmidt, was drafted to play the role of the captain’s Norwegian wife, complete with blonde wig, dress and makeup. Every man had worked out his “identity” as a Norwegian sailor or officer, right down to fake family letters, photos, clothing and personal idiosyncrasies. They chewed tobacco and learned the words to ribald Norwegian drinking songs. Luckner himself learned to chew tobacco, reasoning that if asked a difficult question, he could roll the plug in his mouth, ponder a moment, then spit elegantly.

By early November 1916 the ship was ready, fully loaded and manned. All it needed to pass through the blockade was a foolproof identity. The bark Maleta, which was simlar to Seeadler, was loading in Copenhagen. Luckner traveled to the port and, reassuming his former identity as Phelax Luedige, signed on as a longshoreman. One night he crept aboard and stole the ship’s logbook, giving Seeadler its bona fide identity. Unfortunately, the German Admiralty delayed the raider’s departure until after the real Maleta had sailed. The cover story wouldn’t work.

Luckner changed the name on the stolen log and all ship’s papers to Irma, a bark of dubious registry in truth named after the captain’s fiancée. But the erasures and alterations proved too obvious. Maintaining his composure, Luckner directed the ship’s carpenter to use an ax to break out a few portholes and smash railings and bunks, then drench everything in seawater. When the job was done, it appeared as though the bark had been through a violent gale. It only seemed natural its sodden and stained papers were hard to read.

Seeadler finally left Hamburg on December 17. The first obstacle it encountered was a field of bristling naval mines. Fortunately, a gale came to the ship’s aid, forcing it to sail heeled far over on its beam-ends and thus allowing it to glide safely over the submerged mines. Then Seeadler ran afoul of the armed merchant cruiser HMS Avenger, whose captain ordered the bark to heave to for inspection. The Royal Navy officer leading the boarding party saw only a loaded lumber ship, recently battered by Baltic storms and crewed by a gaggle of smelly, undisciplined Norwegians who showed little respect for his rank or duty. The bark’s captain, a brute of a man named Knudsen with a plug of tobacco wedged in his cheek, showed the British officer the water-stained and nearly unreadable papers. In his thick Norwegian accent Knudsen introduced his homely blonde wife, Josephine, who was laid up on the damp cabin settee with a painful toothache. The Royal Navy officer saw no further reason to detain the obviously innocent Norwegian bark and returned to his ship. As Avenger steamed away, its signal flags spelled out Bon Voyage.

Seeadler had passed its first test. As the bark cleared the British Isles and headed out to sea, Luckner ordered its disguise shed. Crewmen dutifully cast the lumber overboard to free up the ship’s two guns, though the captain retained trace camouflage so as to lure unsuspecting prey into Sea Eagle’s claws. Thus prepared, Luckner sailed into the broad North Atlantic in search of prizes. His success would earn him the nickname “Sea Devil.”

Luckner’s orders directed him to attack only other sailing ships. While the very idea of a nearly 30-year-old bark being able to capture a modern steamship was ludicrous, the challenge proved too tempting for the daring young captain to pass up. He had his first chance on Jan. 9, 1917, when the mainmast lookout spotted smoke on the horizon. The source turned out to be the 3,268-ton British steamer Gladis Royle, bound for Buenos Aries with a cargo of coal. After running up the Norwegian flag, Luckner used what became his signature ploy—a request for a chronometer reading. This was common for sailing vessels, which needed accurate time for navigation. In response Gladis Royle hove to under the bark’s port bow—at which point Luckner ordered the German naval ensign raised and a shot fired across the steamer’s bow. Three more shots forced the British captain to stop his engines and row over to the German ship. “You fooled me bloody well!” he fumed at the grinning German captain.

The captive crewmen were brought aboard Seeadler and quartered below, while German sailors rigged explosive charges along the steamer’s hull. That night Luckner’s first victim went to the bottom.

The next day Seeadler found another—the 3,095-ton British steamer Lundy Island, carrying sugar from Madagascar. Its captain, however, was not taken in by the request for a chronometer reading and made a run for it. Luckner had the German ensign raised even as his gunners fired two shots at the steamer, striking its funnel and hull. Beaten, its captain surrendered, and its crew was taken aboard. In two days Luckner had captured and sunk two British ships without a single life lost.

Over the following days the captive British captains engaged in a spirited chess tournament while their crews enjoyed the run of the German ship, albeit under guard. Thanks to Luckner’s courtly treatment of his wards, there were no problems. Remarkably, the German captain paid the prisoners their regular wages while aboard. Even more astonishingly, after Luckner offered a reward of 10 pounds sterling and a bottle of champagne to the first man—German or British—to sight a ship, almost every prisoner and even their captains lined the rails and clambered into the rigging to watch for Seeadler’s next target. “Never,” Luckner recalled, “had a ship such a lookout.”

On January 21 lookouts spotted the 2,199-ton French bark Charles Gounod, Luckner approaching it with the same request for a chronometer reading. Its captain quickly capitulated, and Seeadler’s crew brought aboard Gounod’s sailors and several cases of good French wine before Luckner sank the sailing ship. Over the next few weeks Seeadler captured and sank three more windjammers—from Britain, France and Italy—without resistance, and the hold was soon packed with more than 100 prisoners.

In just a month Seeadler had dispatched six ships. And still the wily Sea Devil pressed on toward the South Atlantic. On February 19 Luckner confronted a ghost from his past when he captured the 2,432-ton British bark Pinmore, on which he had sailed as the young runaway Phelax Luedige. With a sense of nostalgia, Luckner rowed over alone to the old windjammer and walked the decks of his youth. Then pragmatism intervened, as he and several crewmen sailed Pinmore to Rio de Janeiro to purchase needed supplies. With his usual flair, Luckner got away with the daring venture and rendezvoused with Seeadler a few days later. He then had to give what he later described as the most difficult command of his naval career. With a heavy heart he ordered Pinmore sunk. Staying below in his cabin, he tried not to listen to the dull rumble of the charges that sank the much-loved relic of his past.

By then Luckner had weightier concerns on his mind. While passing himself off as a Norwegian in Rio, he’d met a Royal Navy officer from the light cruiser HMS Glasgow. The man told “Captain Knudsen” his ship and the protected cruiser HMS Amethyst were preparing to hunt for a German raider then operating off the Brazilian coast. Their quarry was actually Seeadler’s sister raider SMS Möwe. But Luckner wasn’t taking any chances. He bent on full sail and headed south toward Cape Horn, at the tip of South America. En route he sank three more windjammers.

On March 11 Seeadler’s lookouts spotted the 3,609-ton British steamer Horngarth, which boasted not only a conspicuous deck gun, but also a transmitter Luckner had to put out of action before its radioman could raise the alarm. When the steamer’s captain ignored Luckner’s standard request for a chronometer reading, the German captain had his crew fire up a smoke generator, ignite magnesium in a plate atop the main deckhouse and raise a distress flag, something no honorable captain could ignore. As Horngarth approached, Luckner had “wife” Josephine—“that rascal Schmidt” in drag—parade demurely along the deck to distract the British sailors. He then hoisted the German ensign and fired a shot directly into the radio room. When Horngarth’s crew made motions to return fire, Luckner had selected men with megaphones yell out in English, “Torpedoes clear!” That made the British captain back down and surrender. But Luckner’s perfect record had been broken—a British sailor had died from wounds during the standoff. The Germans and their captives buried him at sea with full honors.

By then Seeadler held more than 275 prisoners, a burden that prompted Luckner to make good use of his next prize, the 1,833-ton French bark Cambronne. Its captain was relieved to learn his ship would not be sunk but was to transport Seeadler’s prisoners to Rio. Luckner had Cambronne’s topgallant mast and other spars and sails removed to slow it, then put his prisoners aboard. With the French vessel still in view, Seeadler’s crew made a show of sailing north. Only as night fell did Luckner turn back south, headed for the Horn. But unlike his other ruses, this one didn’t work. The Royal Navy had surmised Seeadler was headed for the Pacific and sent Glasgow and Amethyst to find and sink the raider.

In April 1917 the United States declared war on Germany, and Luckner expanded his target list to include vessels flying the Stars and Stripes. Between June 14 and July 8 the Sea Devil captured and sank three small American schooners, A.B. Johnson, R.C. Slade and Manila. Well under 1,000 tons each, they were slim pickings compared to what he had found in the Atlantic, but he had other concerns. The Royal Navy was hunting for him, and he was low on provisions.

On the last day of July the German raider anchored in the calm lagoon of Mopelia (Maupihaa) atoll in the Society Islands, the crew and prisoners all going ashore to feast on turtle soup, lobster, eggs and fruit. But disaster struck when a strong current caused Seeadler’s anchor to drag, and the current drove the bark onto a submerged reef, breaking its keel in five places. Luckner knew it was the end of the voyage. He ordered everything salvageable taken off and had his noble windjammer burned to the waterline. With their captives’ help, the Germans then cobbled together a seaside village of sorts using the ship’s timbers and sailcloth.

But the audacious Sea Devil refused to run up the white flag. Outfitting one of the ship’s launches with sails, provisions and weapons, Luckner set out with five volunteers, resolving to capture the first interisland trading ship they encountered. But on Sept. 21, 1917, after a fruitless 2,300-mile journey to Fiji, they reached the end of the line. Confronted by a British officer and soldiers, and realizing resistance would only result in needless bloodshed, Luckner surrendered. His nine-month odyssey had ended, and he and the men who had sailed with him in the launch were sent to a prisoner of war camp in New Zealand. He managed to briefly escape that December—by sea, of course—before spending the remainder of the war in captivity.

Despite the jealous skepticism of Luckner’s fellow German naval officers, the concept of a sail-powered commerce raider had proven its value. During its time at war Seeadler had sunk 14 ships—including three steamers—totaling nearly 30,000 tons and had tied up Allied warships and other resources that might otherwise have been put to better use. In Luckner, the Germans had found the perfect man for the job. His wartime memoirs were a best seller in Germany, and he became a sought-after speaker, respected and revered for his daring, cunning and chivalry to his enemies. The Sea Devil and his gallant Seeadler were truly the last of their kind.

Mark Carlson has been an aviation and military writer for more than a dozen national magazines and is the author of three books, the most recent being The Marines’ Lost Squadron: The Odyssey of VMF-422. For further reading he recommends The Windjammers, by Oliver E. Allen, and Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea, by Robert K. Massie.