On the eve of Saratoga, a high-born wife takes her youngsters to North America to find her husband, a German mercenary. What could go wrong?

Catching sight of Quebec, Baroness Frederika Charlotte Riedesel felt her heart pound. Early on that Wednesday morning—June 11, 1777—the baroness spied from aboard ship a cluster of stone buildings perching on a hilltop between rivers named for Saints Lawrence and Charles, and beyond the little city ranks of forested mountains. It had been nearly a year since Baroness Riedesel, 30, and her small daughters left Brunswick, a German-speaking duchy located in central Europe. They and their servants were to join her husband, an officer whose unit of Brunswickers had been hired to fight with the British Army. As far as Frederika knew, her Friedrich was stationed at Quebec.

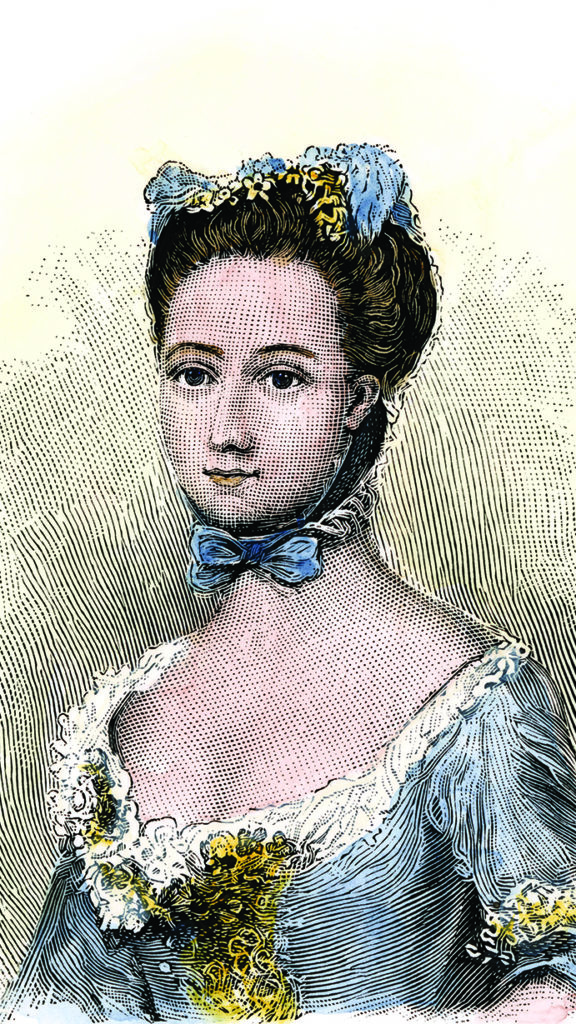

In a memoir, the baroness described how, as their vessel entered the harbor, the crews of ships already at anchor fired salutes. A dozen sailors in white wearing green sashes rowed a boat to the ship to escort her to shore—and to deliver bad news. Days before, General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel had left Quebec leading his 3,000 troops as part of a 7,000-man British force marching south to quell a rebellion in the Empire’s other North American colonies. He had left a letter saying where he had gone and explaining that he would send for her and the girls in due time. With her neat coif, pale skin, and elegant dresses, the blue-eyed baroness resembled a porcelain figurine, but she was also strong-willed and determined. Rather than wait for her husband’s summons, she decided to set off into the North American wilds to find her man. Doing so put her in the ranks of camp followers—civilian women with ties personal and practical making them part of 18th century soldiering, even on battlefields.

In the 1700s there was no such thing as Blitzkrieg—the Hundred Years’ War was more the model. Accompanying a soldier on campaign was the only way many military families could have lives together. Commanders trying to keep desertions down grudgingly accepted women’s presence in garrison and in the field. Upper-class wives who could afford the outlay kept semblances of households, setting the table as lavishly as possible and hosting their husbands’ fellow officers and their spouses, but most women in this situation had far smaller purses. To pay their and sometimes their offspring’s way, these camp followers—so called because on the march they generally were at the rear, with the baggage train—worked at armies’ fringes, helping with the laundry, cooking, sewing, and tending the wounded. About 300 women accompanied British General John Burgoyne’s army on its push south from Canada on the Northern Campaign of 1777. Baroness Riedesel’s memoir chronicles camp-follower life with a noncombatant’s vivid perspective on important battles and actors of the American Revolution.

Frederika Charlotte von Massow wed Friedrich Adolf Riedesel, baron of Eisenbach, in 1762 in Neuhaus, Brunswick. Frederika was 16, daughter of a general in the army of Prussian King Frederick II, aka Frederick the Great. Friedrich was 24 and the favorite aide-de-camp of Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick, one of the 18th century’s nearly 100 German-speaking states. He pronounced his family name “Ree DAY zell.” On young Riedesel’s behalf, Duke Ferdinand asked Frederika’s father if his subaltern could have her hand, a model of proper procedure. Yet the couple also enjoyed a love match, having grown close at her family home in Minden, where Friedrich had been Frederika’s favorite among many young officers to come calling.

The Riedesels had been married for 13 years when the duke of Brunswick appointed Friedrich to lead a brigade that England’s King George III had hired to fight in America. With his forces stretched across a global empire and the Americans in revolt, the king needed more troops. German states historically had provided multiple nations with boots on the ground—for a price. When King George advertised for mercenaries, six states jumped at the opportunity. Hesse-Cassel sent the most, about 17,000; German troops came to be known in America as “Hessians.”

Brunswick came second with 6,000 soldiers. Other forces hailed from Hesse-Hanau, Anspach-Bayreuth, Waldeck, and Anhalt-Zerbst.

When Friedrich announced his impending departure for the New World, Frederika, who had grown up following her father’s armies and was pregnant with their third child, said she would come too and bring along Augusta, 4, and Frederika, 2. Friends’ tales of cannibalistic Indians were no deterrent. She and Friedrich agreed he would go first, and she would follow later. He left on February 22, 1776, frequently exchanging heartfelt letters with her. “Dearest wife: Never have I suffered more than upon my departure this morning,” Friedrich wrote in his first letter home. “My heart was broken.”

Within months, in a newly built carriage, the two Frederikas, Augusta, and 10-week-old Caroline were heading west, attended by several servants. Rockel, the forester from Frederika’s father’s estate, packed his firearms and came along as her footman. In one town, residents warned of bandits, some of whom recently had been caught and strung up. Passing through woods in a carriage that twilight, the baroness felt something fuzzy come through a window and strike her in the face.

“It was the body of a hanged man with woolen stockings!” she wrote.

In England, she visited King George and Queen Charlotte. The queen told the baroness she admired her guest’s courage and would be asking about her progress. Save for the royal audience, the Riedesels’ British interlude was tedious. The baron had arranged for his wife to make the trans-Atlantic crossing with the wife of a British officer he knew; the woman, Hannah Foy, repeatedly delayed their departure until winter shut down the sea lanes. At last putting to sea the following spring, Frederika had new cause to regret her association with Madame Foy. Their ship’s captain was an “old and intimate friend of Madame Foy,” who dared not “refuse to him those liberties to which he had formerly been accustomed.” And Madame Foy’s pretty chambermaid not only caroused at night with the ship’s sailors but pilfered the captain’s wine, then tried, unsuccessfully, to blame Rockel. “I felt deeply for this honest man,” the baroness said.

Frederika’s decision to set out after Friedrich arose from fear that once the Northern Campaign had gotten under way, she would never see him again. Lady Mary Carleton, wife of Quebec Governor Guy Carleton, proffered invitations to dine and stay at her official residence. Frederika came for dinner but declined lodging. She instead found a boatman to take her and her party 20 miles up the Saint Lawrence to Point aux Trembles. Landing in the middle of the night, the travelers transferred into a trio of two-wheeled open carriages called calashes. The baroness held her infant on her lap, tied Frederika to the seat beside her, and sat Augusta on the calash floorboards at her feet. The servants and luggage—including cases of Friedrich’s favorite wines—followed in calashes of their own.

The baroness promised their drivers a reward for speed. “I knew that if I would reach my husband, I had no time to lose,” she said. At a locale where they had to cross several rivers a storm arose. The only vessel available was an odd contrivance, narrow and made of bark—a canoe. Terrified, the voyagers sat, mother and children at one end, servants at the other, trying to keep an even keel. A cascade of hail set little Frederika to screaming and flailing. The boatman shouted at the baroness to control her child, lest the canoe capsize. On the far bank, they learned two fishermen had drowned that way nearby. “I thanked God that I had accomplished the passage so successfully, and yet it was not pleasing to me to know of my danger,” the baroness said.

His wife and daughters caught up with Baron Riedesel at Chambly, near Montreal—but only after mistaking him for a Canadian. Friedrich looked ill and feeble and even in the heat of summer was wearing a long woolen coat with blue and red fringe at the hem. Weeping, little Frederika, who associated her father with portraits of a handsome bewigged man in a brilliant blue and gold uniform, shied away from the seeming stranger.

“No, no! This is a nasty papa,” she wailed. “My papa is pretty.”

“The very moment, however, that he [Friedrich] threw off his Canadian coat, she tenderly embraced him,” Frederika wrote.

The Northern Campaign, as conceived by Burgoyne and Lord George Germain, secretary of state for the colonies, called for a large British force to push south from Quebec to Albany, New York, and meet another marching north from New York City at the order of General William Howe, senior British commander in America. The aim was to control the Lake Champlain and Hudson River waterways, separating and isolating the northern and southern colonies. The British then could focus on reducing New England, in their eyes the wellspring of revolutionary sentiment. At first the plan went smoothly. As the superior British force was nearing American-held Fort Ticonderoga, on Lake Champlain, Continental General Arthur St. Clair decided he had no choice but to evacuate that dilapidated bastion to save his 2,500-odd troops. In the following weeks, General Philip Schuyler, senior commander of the Americans’ northern forces, kept up the retreat, abandoning Fort Anne, located about ten miles south of Lake Champlain, Fort George, ten miles west at the southern end of the lake of the same name, and Fort Edward, some 20 miles south of Fort George. Burgoyne reported his triumphs in letters to Lord Germain in London.

Schuyler felt that he lacked the strength to mount a direct attack, but as he was withdrawing, he undertook a skilled campaign of obstruction, blocking roads, damming streams, and dismantling bridges. Progress across the wet, mountainous terrain grew increasingly difficult for Burgoyne’s troops. At Bennington, Vermont, thousands of militia gathered to repel an eastward British probe. American attacks on Fort George led Burgoyne to abandon that and other rearguard locations, in effect severing his force’s ties to Canada (“Desperate Hours,” August 2019).

In August, Burgoyne established a headquarters at Ford Edward. The Riedesels spent three happy weeks there—though food did run short. Baroness Riedesel, happy to have her family together again, felt “beloved by those by whom I was surrounded.” The presence of a handful of other fine ladies, including Lady Harriet Acland, wife of Colonel John Dyke Acland and author of her own memoir of the 1777 campaign, reinforced soldiers’ pride and nostalgia for home.

Anglicizing her name’s proper pronunciation. British soldiers fondly bestowed the nickname “Red Hazel” on Baroness Riedesel, The army resumed its march south. The baroness reported morale to be high. Burgoyne proclaimed, “The English never lose ground.”

Victory appeared to be certain. The baroness remarked on the beauty of the countryside she was passing through, but also noted its bleak emptiness; many inhabitants had fled to join the rebel army. “In the sequel this cost us dearly, for every one of them was a soldier by nature, and could shoot very well,” she wrote. “Besides, the thought of fighting for their fatherland and their freedom, inspired them with still greater courage.”

Compounding the perils facing the British and German column, Howe had not dispatched that promised force to meet Burgoyne at Albany. Lord Germain had failed to give Howe a clear order to do so, and the general decided that that year’s priority would be an attack against the American capital at Philadelphia. By the time Burgoyne severed his army’s ties to Canada, he was on his own, and knew it, with his foe growing stronger every day. Congress had decided to relieve Schuyler, a wealthy landowner many members disliked because of his continual retreats. The politicians replaced Schuyler with General Horatio Gates and instructed neighboring states to send more militia. Buoyed by victory at Bennington and animated by reports of atrocities by Indians attached to Burgoyne’s army, thousands enlisted. When Gates arrived at Van Schaik Island, on the Hudson River, to take command in late August, his army numbered about 10,000. He believed his men ready to do something new: advance on the enemy.

Gates’s army occupied Bemis Heights, one of several bluffs overlooking the Hudson near the town of Saratoga. On September 19, the British ordered a force to flank the American position to its west. The Americans went out to meet them. The result was a bloody clash in a clearing amid dense forest called Freeman’s Farm. At day’s end the British held the field, though at Pyrrhic cost, having taken heavy and irreplaceable casualties without improving their tactical position. Rations were low. The region’s foliage was starting to turn—a warning of winter. Friedrich Riedesel argued that the British should retreat to a more secure location to await reinforcements, and, should no reinforcements appear, to Canada. Burgoyne, fearing permanent harm to his reputation if he were to withdraw, decided to risk all on another attack. On October 7, he sent a large number of troops in another flanking action. His men encountered more Americans than he had been expecting. Near Freeman’s Farm, rebels mowed down redcoats pouring into a wheat field. Fighting as if possessed, the American General Benedict Arnold drove the British troops back to their own outer works. Burgoyne’s gamble had ended in disaster.

All the Riedesels were caught in the gears of October 7 and the days after. The baroness wrote that her husband’s breakfast at the house where they were staying was interrupted by the sounds of his troops mustering for that day’s fateful events: it was time for him to leave. “Our misfortunes may be said to date from this moment,” she wrote. As the day passed, rifle shots built to a murderous crescendo. Feeling “more dead than alive,” she supervised dinner preparations; the evening’s guests were to include General Simon Fraser, commander of the British advance unit. Within hours later, Fraser did arrive—mortally wounded and borne by troops who moved aside the dining table to lay their leader down. Groaning all night, the dying man repeatedly asked the baroness to forgive his intrusion. He sent Burgoyne a message asking that he be buried at 6 the next afternoon on a nearby hill. Fraser died that morning. Burgoyne decided to honor this request, much to the dismay of the baroness, who thought the army should begin its retreat immediately. “This occasioned an unnecessary delay, to which a part of the misfortunes of the army was owing,” she said.

The mass of healthy soldiers, wounded men, horses, and baggage train lumbered north by fits and starts. During one pause, Friedrich Riedesel climbed into his wife’s carriage and slept for three hours with his head on her shoulder. Hungry men asked the baroness for food; the commissaries had not distributed any provisions. She reprimanded a Burgoyne aide for the oversight, leading to an appearance 15 minutes later by the commander himself, promising to remedy the situation.

“I believe that in his heart, he has never forgiven me this lashing,” the baroness wrote later.

As the retreat was ending its second day, the column came under attack. Friedrich Riedesel sent word for his wife to take refuge with the children and servants in a farmhouse that had been housing a British field hospital. As they approached the one-and-a-half story, gambrel-roofed building with a chimney on each end, she spied riflemen across the Hudson aiming at them. She threw the children and herself to the carriage floor. “At the same instant, the churls fired and shattered the arm of a poor English soldier behind us,” Frederika said. Amid a sustained enemy barrage, she and her girls and servants scrambled into the ad hoc

hospital’s cellar, where they spent a grueling night with other women and children and wounded soldiers. “A horrible stench, the cries of the children, and yet more than this, my own anguish, prevented me from closing my eyes,” the baroness wrote. In the morning, the firing eased. Frederika directed volunteers to sweep the 45’x33’ cellar clean and fumigate the space by sprinkling vinegar on embers. No sooner was the work done than the enemy barrage recommenced, cannon balls crashing through rooms overhead where army surgeons were working. “One poor soldier, whose leg they were about to amputate, having been laid upon a table for this purpose, had the other leg taken off by another cannon ball,” Frederika said. The baroness distracted herself tending to the wounded. An officer in the cellar helped calm the children with his imitations of a cow’s bellow and a calf’s bleat. “If my little daughter Frederika cried during the night, he would mimic these animals, and she would at once become still, at which we all laughed heartily,” she said. The party had sufficient food but soon ran short of water. “In order to quench thirst, I was often obliged to drink wine, and give it also to the children,” the baroness said. The general, who was camped nearby with his troops but frequently checked in on his family, drank so much he alarmed his spouse and the faithful Rockel. “I fear that the general drinks so much wine because he dreads falling into captivity and is therefore weary of life,” Rockel said. Soldiers’ efforts to fetch water from the river drew fire from enemy riflemen, so one of the young wives volunteered to try. “This woman, however, they never molested; and they told us afterward that they spared her on account of her sex,” the baroness said. The Riedesels’ ordeal in the cellar lasted for six days until Burgoyne requested a ceasefire to discuss surrender terms.

Saratoga redirected the Revolution, brightening American hopes of prevailing against the world’s leading military power and paving the way for an alliance with France. The British defeat ended the war for the Riedesels. After a long but relatively comfortable captivity at Boston and then Charlottesville, Virginia, during which the baroness helped her husband battle illness and despondency, Friedrich Riedesel was released on parole. His family was allowed to rejoin British forces in New York City. Riedesel later was exchanged for an American. He returned to active duty and was stationed back in Canada. At war’s end in 1783, the family headed for Europe with an additional member: daughter America. In London, the king and queen received the family and thanked them for their service. Back home in Germany, the baroness had two more children and in 1800, with help from daughter Augusta’s husband Count Heinrich von Reuss, brought out a memoir, “The voyage of duty to America; letters of Mrs. General Riedesel, upon her journey and during her six years’ sojourn in America, at the time of war that country, in the years 1776-1783, written to Germany.” Baroness Frederika Charlotte Riedesel died in Berlin in 1808. She was 61.

_____

Pitching In

Wives following common soldiers in 18th-century armies lived very differently from their aristocratic counterparts with ties to the officer corps. They got army rations, but had to work for them, performing odd jobs. Cooking and sewing was usually a male preserve, but wives would help out. Women commonly handled washing. Assisting in field hospitals, one of the few paid jobs open to camp followers, appears to have been among the most desirable. Women often worked as sutlers, selling commodities—primarily alcohol—to the ranks. Typically, each regiment had one sutler; others sometimes could keep shops in the vicinity of an encampment.

To a degree, the British army controlled soldiers’ marriages, expecting wives to work hard and not cause trouble. The army tried to prevent the presence of prostitutes but was not always able to keep whores from gathering nearby, especially when it set up camp near urban centers; some commanders required periodic screenings for venereal diseases. Few reports of adultery involving soldiers’ wives are on record, but many officers, rankled by the women’s presence, took a hostile attitude toward them. The Continental Army was more relaxed; many soldiers were married before they enlisted. When troops left garrisons for the field, women’s presence usually was restricted further. The number of women accompanying British regiments during the Revolution varied but averaged roughly one woman for every eight soldiers, or about 6,000 at its peak. Muster rolls suggest about 1,600 on the American side, or about one woman per 30 men. The Americans were fighting much closer to home, many on short-term enlistments, and the army had fewer resources for soldiers’ wives.

The numbers of accompanying women and children tended to grow when an army remained awhile at one location and soldiers fraternized with locals. During the Revolution, which had aspects of a civil war, armies moving across the countryside attracted more followers of all sorts as supporters of one side or the other sought protection from the foe. Those 300 women accompanying Burgoyne’s army at the beginning of the 1777 campaign were joined by hundreds of others as Loyalist inhabitants, perceiving the British column as safe, joined the march.

En route, women historically clustered at the column’s rear, with the baggage train. Most walked, often carrying belongings and children. During battles, women usually stayed in the rearguard, but sometimes officers directed them to bring water to troops. American Mary Ludwig Hayes came along two years later to join her husband, who was serving with a company of the Pennsylvania Artillery. At the Battle of Monmouth, New Jersey, she supplied men on the line with drinking water, leading soldiers to nickname her “Molly Pitcher.” When her husband collapsed from heatstroke, she took his place at the cannon and kept firing at the enemy. —Jonathan House