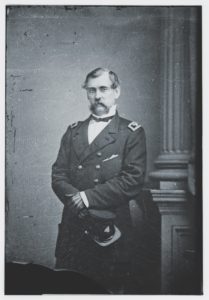

From his early days at the U.S. Military Academy, Ulysses S. Grant placed Charles Ferguson Smith in elite company. “I regarded General [Winfield] Scott and Captain C.F. Smith…as the two men most to be envied in the nation,” Grant would write in his Personal Memoirs. “I retained a high regard for both up to the day of their death.”

Grant graduated in West Point’s Class of 1843, the same year Smith—15 years his senior—completed his term as the academy’s commandant of cadets. The two served together during the Mexican War, but their military careers soon headed in abruptly different directions. By the outbreak of the Civil War, Smith had become one of the U.S. Army’s most celebrated officers. Grant, meanwhile, having left the service in disgrace in July 1854, was working at his father’s tanning business in Galena, Ill.

Although the Civil War provided the two a welcome reunion in the Western Theater, it would prove brief and painful. Smith died in April 1862 due to complications from a freak injury suffered while he was jumping into a boat in Savannah, Tenn. Grant, of course, eventually became the Union Army’s top general and finally engineered Northern victory in 1865. How different the outcome would have been had Smith survived his wound is one of the war’s many intriguing unknowns.

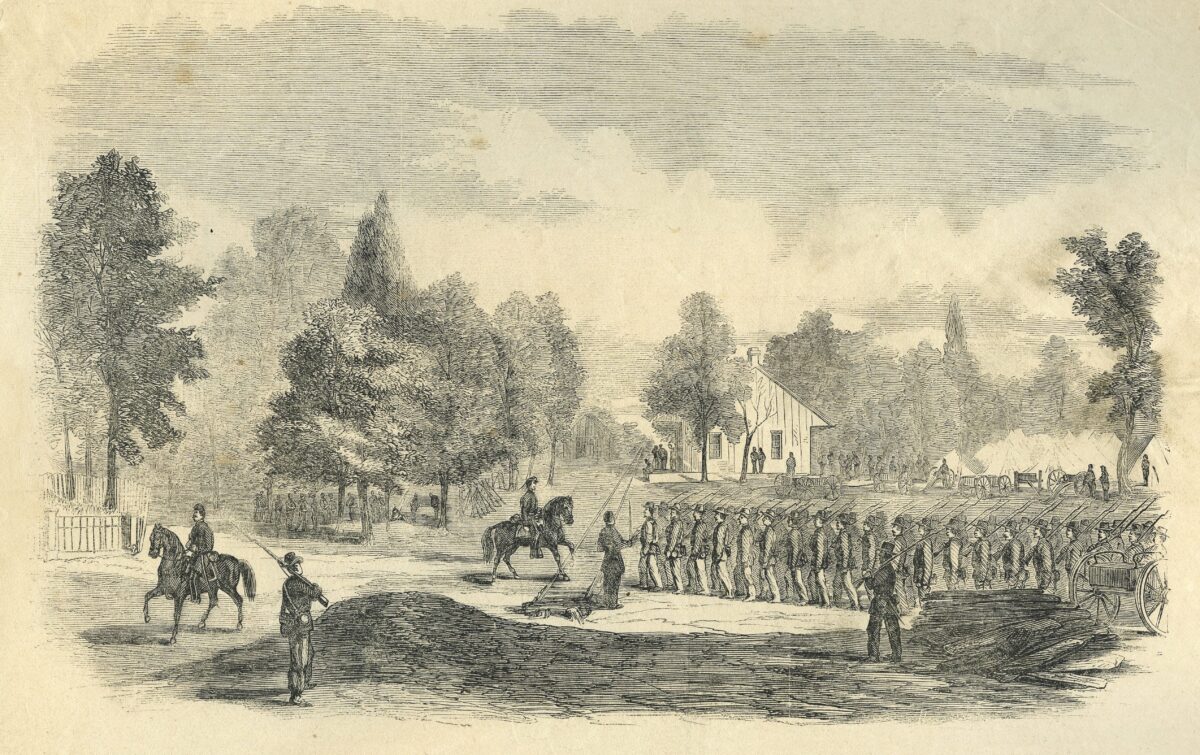

In the late summer of 1861, Grant and Smith were both serving in the Department of the West—Grant, a brigadier general, as commander of the District of Southeastern Missouri; Smith, a brevet brigadier, the District of Western Kentucky. Based in Cairo, Ill., Grant learned on September 6 that a Confederate force under Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow had occupied Columbus, Ky., and was preparing to attack nearby Paducah. Grant informed Department of the West commander Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont of Pillow’s invasion and announced he “was taking steps to secure” Paducah. Without Frémont’s approval, however, he headed downriver with a force of two gunboats, three steamboats, two regiments under Brig. Gen. Eleazer Paine and Colonel John McArthur, and four light artillery pieces.

Paducah would fall without a struggle when the small defending force under Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman fled rather than confront Grant. To the alarmed residents, Grant promptly read a proclamation of peace and also instructed his men “to take special care and precaution that no harm is done to inoffensive citizens.”

Placing the city under Paine’s command, Grant returned to Cairo. Paine, however, disregarded Grant’s orders. Considering Paducah a conquered town, he treated the pro-Confederate locals harshly, arresting several citizens and allowing his undisciplined volunteer troops to commit robbery and vandalism. Some residents resorted to sabotage, even poisoning wells used by soldiers and cutting telegraph lines.

Transferred from his command at Fort Columbus, N.Y., in August, Smith was soon given command of the District of Western Kentucky and replaced Paine at Paducah. The new commander relented that the locals were in “hot secession,” but he would be treated in a better light by them by his decision to treat them fairly. That at least put an end to the rampant pillaging and stealing.

Smith’s first few days at Paducah were marked by a flurry of activity as he organized his command and prepared for a potential attack by Pillow’s Confederates. Everyone was “exhorted to learn and discharge their duties” and, soldiers were ordered to “sleep on their arms.” Smith conceded that his men did not look “much like soldiers, but he thought they might prove to be excellent.” Still, he complained that he had only two officers from whom he could expect any assistance: Paine and Major Joseph D. Webster.

Pleased with Smith’s posting, Grant finally had the opportunity to meet his former mentor at Paducah on September 30. Ironically, by virtue of his earlier appointment, Grant was Smith’s superior officer, which made for a potentially awkward situation. A nervous Grant later admitted to shrinking “like a modest schoolboy” in anticipation of the meeting.

Even though he outranked Smith, Grant said, “It does not seem quite right for me to give [him] orders.” To Smith’s credit, the reversal in position never bothered him. He expressed pride in his former pupil.

At their meeting, Smith and Grant discussed plans for both “defense or attack,” and when it had finished, Grant revealed that his admiration and esteem of Smith was even greater because “there was not the slightest trace of jealousy or disappointment in [his] manner.” Their “private and personal conferences” would only increase their friendship, he noted.

Smith’s brand of discipline did impact his rough-hewn volunteers, but after two months of training many realized the general was teaching them valuable combat skills. A colonel admitted to Smith: “The boys didn’t like [you] much at first; thought you were too damned strict; but they think it all right now and say you are just the person they want to make them soldiers.”

Nevertheless, newer recruits were quick to challenge Smith’s authority, leading to what would be the most difficult period of his military career. The adversity was spurred by a Paducah resident’s decision to express his political sentiments, which blossomed into a near-mutiny among one of Smith’s regiments.

As reported in The St. Louis Democrat, a secessionist known only as Woolfolk had hung a Rebel flag out a window and had “hurrahed for Jeff Davis” as Union troops passed his house. When reported to Smith, he elected not to interfere. According to the paper, Smith’s failure to stop this demonstration “caused great indignation among the troops, and doubts of his loyalty were freely expressed…”

When Woolfolk’s actions were reported to Brig. Gen. Lew Wallace, one of Smith’s subordinates, Wallace sent his aide-de-camp and a squad of soldiers to order Woolfolk to take down the “traitorous flag” and “erect the Stars and Stripes over his house.” Woolfolk refused, and appealed to Smith for assistance. After Wallace’s aide did as instructed, one of Smith’s men arrived and ordered the Union flag taken down. The order was refused, Wallace telling Smith the flag should not be lowered “while there was a live man in his brigade.”

Worse for Smith, Paine supported Wallace’s actions and leaped on the opportunity to embarrass his commander. As the Democrat concluded: “The affair has created intense excitement among the soldiers, and Wallace’s insubordination is enthusiastically approved.”

The flagrant noncompliance dismayed Smith. Not only had the officers, belonging to the 11th Indiana, refused to obey his orders, they had also violated Grant’s directive not to harm “inoffensive citizens.” In Smith’s view, Wallace was guilty of failing to control his officers and soldiers and enforce Grant’s orders.

Although the behavior of the Indianans bordered on mutiny, Smith realized he needed to move past the incident as quickly as possible in order to prepare his men for potential fighting. Desiring to treat the officers and soldiers of the 11th Indiana in a “kindly spirit,” he decided to use the event as a teaching opportunity. Smith denounced “the transaction as a great violation of good order and military discipline,” believing that after consideration, the guilty parties would recognize the violation’s seriousness.

“In this spirit the Commanding General appeals to the intelligence of officers and soldiers to know that he is sent here by the Government as the protector of a loyal State, which, though occupied by rebel armies, is not an enemy’s country,” Smith said, “and that success requires him by the patient exercise of moderation, obedience, and charity to earn that character from both friends and foes.”

Smith asked the soldiers to demonstrate “by their conduct in the future, their gentleness to friends, and their moderation towards unarmed enemies, living under the shadow of our flag,” the “necessity of order and are willing to enforce it.”

Smith, however, was now fighting on two fronts: internal attacks on his loyalty by fellow officers and politicians and external threats to his command by Confederate forces. In late November, U.S. Rep. Lucian Anderson (Ky.) and a colleague presented a list of complaints “relative to the management and control of the Army of the U.S. at this place” to Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, Department of the Missouri commander. They cited four examples of Smith’s mismanagement: 1) failure to send U.S. troops to rescue a Union man who was later killed by a “band of murderers”; 2) delay in confiscating wheat and hogs that were being sent to Confederate troops in Columbus; 3) refusal to confiscate hogs being purchased by Confederate agents; and 4) actions associated with removal of the Confederate flag from Woolfolk’s house. “Unless some changes are made here,” Anderson warned, “bad results will certainly flow, for the soldiers…are almost prepared to rise against the policy which has thus far been pursued.”

Halleck forwarded Anderson’s accusations to Smith. The general barely had time to respond when new condemnations appeared in the papers. Reported The Chicago Tribune: “General Charles F. Smith, in command of the Federal forces at Paducah, has been making an ass of himself, which is stating the case mildly.” The Tribune claimed under Smith’s weak rule, Union troops had “been subjected to gross insults from disloyal residents, with no chance given to them to fight back.”

In an early December edition, the Tribune added that Smith was “exceedingly unpopular both with the officers and men,” and accused him “of sympathizing with the rebels and refusing to aid Union men who have been driven from their homes, and whose property has been plundered by the secesh.” An editorial in the Cincinnati Commercial likewise blamed Smith for failing to capture Columbus during the Battle of Belmont on November 7, 1861, claiming, “in all the action of that General he favors Secession.”

Smith labeled the attacks “scurrilous and malignant articles.” Some of his friends—“the true soldiers of the camp”—began a vigorous writing campaign to the newspapers on his behalf.

The accusations and innuendo had their intended effect, though. Smith’s confirmation as brigadier general was delayed in the Senate, and Halleck was forced to investigate. Major General George McClellan, the Union Army’s general-in-chief, gave Halleck the authority to remove Smith from command if deemed necessary. Before acting, Halleck sent a delegation of officers to Paducah to inspect Smith’s post and assess its condition.

The officers reported back that Smith’s whole command was in excellent condition and that his forces were “in the best discipline & order of any one in the department,” saying the problems between Smith and his subordinates were caused by others and not Smith. Convinced there were “no real grounds of complaint” against Smith—certainly none “sufficient to justify his withdrawal”—Halleck told McClellan that Smith was “the victim of a base conspiracy among his own subordinates.”

Smith was relieved when Grant’s command was redesignated the District of Cairo and Paine was given command of Union forces at Bird’s Point, Mo. “What a howling on one side, what a rejoicing on the other,” Smith noted with glee. “There never was a more crestfallen man in the world than when he [Paine] received the order to leave here and go to the Bird’s Point…[a] very hell hole.” The general noted his pleasure that while Paine and his “companions in iniquity” were enjoying the prospect of Paine replacing him at Paducah, a “shell fell in their midst.”

Still plagued, though, by rumors and accusations, Smith on December 26 responded formally to each of the charges of command mismanagement against him. The first had cited his “failure” to send troops to rescue from civilian authorities an imprisoned Union man in nearby Mayfield, later killed by a “band of murderers.” Calling it a “private broil” and noting that the “Union” man was justifiably in a local jail for murdering a judge, Smith said he chose not to send a force based merely on a supposition. He also noted that neither Paine nor Wallace “importuned me to send out” a force, and fumed at claims he preferred to protect secessionists and not unionists, declaring, “This imputation on my loyalty is an unmitigated calumny and falsehood.

According to the second charge, Smith had refused to act on Paine’s request to remove supplies intended for Rebel forces at Columbus until he could “get some proper grounds for action.” In response, Smith charged Paine with spending too much time investigating the loyalties of people in Paducah to the “neglect of his military duties.” Many of the arrests based on Paine’s assertions were discharged, he noted. Smith also cited Paine’s failure to obey orders to destroy a mill and bring its flour and grain to Paducah.

To the third charge—that he “failed to send and seize all the hogs in Union county Kentucky”—Smith noted he did not have enough cavalry to authorize such an expedition or to send a large enough force of infantry to secure the animals, as it would weaken his defenses at Paducah.

The final charge concerned Smith’s involvement in the 11th Indiana’s flag-raising incident at the secessionist Woolfolk’s house. Smith called it a sad affair, meant “merely to annoy the family.” He enclosed his order commenting on the 11th Indiana’s behavior and explaining how soldiers should generally conduct themselves.

Colonel George W. Cullum, Halleck’s chief engineer and aide-de-camp, reassured the beleaguered Smith he enjoyed Halleck’s confidence and support of “your old army friends here.” The general, Cullum reported, “defended your reputation and protected you against the political cabal in Kentucky and Washington.”

Complaining, “I have long known that a base conspiracy was on foot…to remove [me] from command and place General Paine in charge,” Smith branded anyone who questioned his loyalty “an unmitigated liar and scoundrel.”

The accusations were the low points of his military career. Smith, in fact, continued to function under a black cloud until his success in battle propelled Grant’s capture of Fort Donelson in February 1862. And then, just two months later, he was gone.

Allen H. Mesch writes from Plano, Texas. He is the author of Teacher of Civil War Generals: Major General Charles Ferguson Smith, Soldier and West Point Commandant (2015).