Letters Reveal the Inner Man:

What we can learn from Joshua Chamberlain’s letters to his wife

Since Ken Burns reintroduced Joshua Chamberlain to a wide audience in his 1990 PBS series, the hero of Little Round Top has been among the most studied and admired figures of that great conflict. As a young boy Chamberlain suffered from a stuttering problem, yet he became fluent in seven languages and taught college-level speech and rhetoric courses. Trained as a minister, he is best known as a warrior, a contradiction that Michael Shaara referenced in the title of his epic novel The Killer Angels. Those contradictions make him all the more fascinating, and an exemplar of the American citizen-soldier. The following previously unpublished letters from the forthcoming May 2012 book Joshua Chamberlain: A Life in Letters, provide more insight into the mind and life of the Union hero.

Exploring Chamberlain’s correspondence reveals a man who was plagued by the same human foibles that confound the rest of us—someone who overcame his personal demons in heroic fashion but was unable to dispatch them from his consciousness. These layers are often peeled back in the letters, speeches and essays that Chamberlain wrote during his lifetime.

More than 1,000 of these letters written to and from Chamberlain remain accessible in historical collections across the country, each of them adding at least some small nuance to the overall picture of his life. Two hundred and seventy of these remained in the possession of distant Chamberlain relatives until the mid-1990s, when the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, Pa., purchased and added them to its extensive collection. For the Sesquicentennial, the museum decided to release the letters in printed form, allowing the general public to read them for the first time.

Excerpted here are five letters. They begin with part of a missive to his wife Fannie, describing the desolation brought about by war and the melancholy thoughts it conjured up for him. But the next letter describes the sights and sounds of life in a “comfortable” camp. He has already gained sufficient confidence to boast that, despite the nearness of the enemy, he is no longer “nervous.”

The remaining letters reveal some of Chamberlain’s motivations for going to war, and also his efforts to transfer out of the 20th Maine Infantry just six weeks before the Battle of Gettysburg. Also included is his unofficial report on the 20th Maine’s role in the fighting there to Brig. Gen. James Barnes, the commander of his division, written just three days after the fighting ended at Gettysburg. The report is from the Maine State Archives.

A portion of what Civil War enthusiasts will likely find the most valuable letter in the collection is also reprinted here: a detailed description of his experiences in front of the stone wall on Marye’s Heights at the Battle of Fredericksburg, which was Chamberlain’s first direct exposure to combat, written from notes that he took while combat was still raging around him.

Why he chose to join the Army and fight:

Warrenton/62 Thursday noon.

Our eating arrangements in moving about in this way are rather droll. The officers do not “draw” rations, we have to shift for ourselves….Monday I had (begged!) a tip of salt tongue 3 inches long, and 2 pieces of hard-bread. Next day 3 cakes bought of a rebel I believe and eaten with grave apprehensions; as five or six Massachusetts men have been poisoned…of pounded glass in cake. Yesterday a few cakes and some cheese bought of a sutler for breakfast and nothing more till 9 P.M. when the col. got hold of some peaches and he and I ate half a peck for supper….I sleep on the ground a blanket under me and the shawl over. After we get a little more established I shall ride over the country a little, visit the picket line in front and more especially the Maine boys in this vicinity.

I wish I could send you something, but this country is perfectly desolate. Nothing seems to flourish here but graves. A few rods a cross the rifle pits in front of us is a little family burying ground under a group of locust trees. Some mother with her six children sleep there “in Jesus” as the inscription says. Sad enough! but sadder far, to think that in the attack that very spot will afford an evident shelter to the enemy from which to annoy us, and will no doubt be the theater of angry strife. Cannon shot will crush the head stones, and tear the mounds. But the dead are happy there, compared with those who live to see these cruel days. That mother and her little ones are no traitors and the storms of shot and shell that will rage around their resting place will not vex their ears.

I declare it almost weakened me to think what this nation is now doing, wholly devoted to mutual destruction! But there is no other way and there are things worth more than life and peace. Nationality—the Law of Liberty, public and private honor are worth far more, and if the Rebels think they are fighting for all that men hold dear, as I suppose some of them really think they are, we are fighting for more, we fight for all the guaranties of what men should love, for the protection and permanence + peace of what is most dear and sacred to every true heart. That is what I am fighting for at any rate, and I could not live or die in a better cause.—You can tell Mr. Tenney and others where we are situation and what our prospects are. Say we are well and cheerful. Write to me often.

Lawrence

Camp Life and a visit from the barber:

Bivouac near Hartwood, VA

Nov. 22 1862

My dearest Fannie,

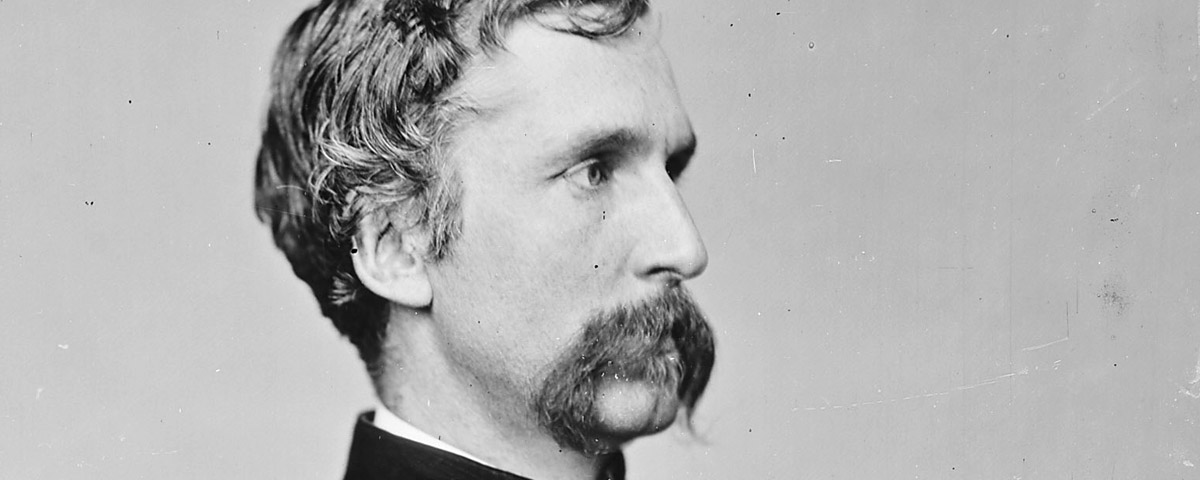

We have been sitting all of us—the Col., Major, Adjutant, Doctor and I around our tent fire which we have tonight in the middle of our big tent, telling ghost stories and other marvelous tales and have enjoyed ourselves very much. Innumerable bugles are sounding the “extinguish light,” and the thought of how much you would enjoy the evening and still more the sight of this city of camp fires and the sound of the bugles, prompt me to write one word to you before I roll myself up in my blanket and go to my sound sleep. Not in the least am I disturbed now by the message which just came from the General “Be vigilant tonight.” You know we are in the midst of the enemy’s country now and have plenty of spies around us; and tonight it happens that we are rather a small body to be left alone so far from aid. But we can be just as vigilant without being nervous. N.B. I don’t get “nervous” now. 12 or 15 hours daily in the saddle is going to rejuvenate me. How you would enjoy this camp—comfortable for once and these bugles again one answering another from all the hill tops around. I wish you could be here. But what should I do with you in the morning my little girl? On the march muddy, cold, and often rainy, you would not be comfortable. My clothes have not been dry for three or four days….Mr. [Adjut. John Marshall] Brown took the opportunity today of cutting my beard to suit his notion of my face. He has left me with a ferocious mustache and my bit of an imperial only. The ends of the mustache he has waxed and twisted and they reach positively the angle of my jaw (you have no angle on yours) and would almost meet under my chin. Mr. B. thinks he has me now to suit him—

especially for a profile. You would not know me….

We are now in Griffins Division, Hooker’s Grand Division. The old corps of Porter is commanded by Butterfield, the brigade by the senior Colonel. You may address simply “20th Regt “Maine” Vols” “Washington D.C.”

We are on for Richmond once more and finally we shall take it this time you may be sure. But we have got to fight all our way from Fredericksburg,

I suppose….

The Battle of Fredericksburg

Camp opposite Fredericksburg December 17th, 1862

I know how much you must desire to hear what I have witnessed & experienced during this eventful week. Let me begin by a few extracts from my note book.

We halted under the partial cover of a slightly rising ground, but precisely in range of the hottest fire, to form our line. The dead & wounded lay thick even here, & fragments of limbs were trampled underfoot. Some of our own men fell here. Suddenly two new batteries opened—it seemed as if the ground were bursting underfoot & the very sky were crashing down upon us—the bullets hissed like a seething sea. In the midst of the hellish din we heard the bugle call the “3rd Brigade.” I was standing with the Col. in front of the colors. He glanced up at the Batteries.

“God help us now,” said he. “Colonel, take care of the right wing!

Forward the Twentieth!” & forward it did go, in line of battle smooth as

a sunset parade, in face of that terrific cross-fire of cannon & rifle, & underneath the tempest of shell—its gallant commander in the van.

For some reason the two Regts. on the right of our Brigade did not advance with us, & our right wing consequently took the flank fire, as well the torrent it breasted in front. On we charged over fences & through hedges—over bodies of dead men & living ones—passed four lines that were lying on the ground to get out of fire—on, to that deadly edge where we had seen such desperate valor mown down in heaps. We moved in front of the line already engaged, & thus covered, it was enabled to retire. Then on the crest of the hill we exchanged swift & deadly volleys with the Rebel infantry before us. Darkness had now come on, & the firing slackened, but did not cease. We felt that we must hold that position, though it was a desperate thing to think of. For the Rebels knowing the ground might flank us in the darkness, & to be found under their very guns at daylight would be offering ourselves

to destruction. To retire however was to expose the whole army to defeat.

So we lay on the trampled & bloody field. Wet & cold it was too, & we had

no blankets—the officers, I mean. Little sleep we had then & there, I assure you. Our eyes & ears were open. We could hear the voices of the Rebels in their lines, so near were they, & could see many of their movements….

[This excerpt is about one-sixth of the entire letter.]

A plan to transfer out of the 20th Maine:

Monday noon,

What would you think, Fanny, of my obtaining the colonelcy of one of the new Regiments to be raised in Maine under the recent Law—the “conscript” or “drafted” Regts.

Would you leave the old 20th? I declare it makes my heart heavy to think of it. But the Col. says if he does not get his appointment, I ought to go in for another Regt. The colonels are to be apptd. by the President Col. Ames thinks we’ve been Lieut. Col. long enough. We have been through two memorable campaigns and very likely shall be into another one before any change can be made. I can imagine there would be the least difficulty in obtaining the place if desired.

The only thing is I have an affection for this 20th. That color somehow has wound my heart up in it—especially since certain fingers that I know of, and was bold enough to kiss, by stealth, some twelve years ago, have consecrated it anew for me. I’ll see it through one more battle, anyway.

Just tell me what you think of my plan or proposal rather. I have not argued the affirmative side. But there are some wonderful advantages in the new Regt.

Think of it for me. You will know a woman’s wit—against man’s cogitations.

Chamberlain’s account of the fighting at Gettysburg:

[July 6, 1863]

General Barnes

Comd 1st Div. 5th Corps

General,

…This Regt. was on the extreme left of our line of battle, & its original front was very nearly that of the rest of the Brigade. At the general assault of the enemy on our lines, my Regt. from the first received its full share. While we were warmly engaged with this line, as I stood on a high rock by my colors I perceived a heavy body of the enemy moving by the right flank in the direction of our left & rear. They were close upon me, & I had but a moment in which to act. The head of their column was already coming to a front, in direction only a little oblique to that of the rest of our Brigade. Keeping this movement of the enemy from the knowledge of my men, I immediately had my right wing take intervals by the left flank at 3 to 5 paces according to the shelter afforded by the rocks & trees, thus covering the whole front then engaged; & moved my left wing to the left & rear making nearly a right angle at the color.

This movement was so admirably executed by my men, that our fire was not materially slackened in front, while the left wing was taking its new position. Not more than two minutes elapsed before the enemy came up in column of Regiments with an impetuosity which betrayed their anticipation of an easy triumph. Their astonishment was great as they emerged from their cover, & found instead of an unprotected rear, a solid front. They advanced however within ten paces of my line…advancing & firing rapidly. Our volleys were so steady & telling that the enemy were checked here, & broken. Their second line then advanced, with the same ardor & the same fate, & so too a third & fourth. This struggle of an hour & a half, was desperate in the extreme: four times did we lose & win that space of ten yards between the contending lines, which was strewn with dying & dead. I repeatedly sent to the rear reports of my condition, that my ammunition was exhausted, & that I could hold the position but a few minutes longer. In the mean time I seized the opportunity of a momentary repulse of the enemy, to gather the contents of every cartridge box of the dead & dying, friend & foe, & with these we met the enemy on their last & most desperate assault. In the midst of this, our ammunition utterly failed, our fire, as it was too terribly evident, had slackened, half my left wing lay on the ground, & although I had brought two companies from the right to strengthen it, the left wing was reduced to a mere skirmish line. Officers came to me, shouting that we were “annihilated”, & men were beginning to face to the rear. I saw that the defensive could be maintained not an instant longer, & with a few gallant officers rallied a line, ordered “bayonets fixed,” & “forward” on the run. My men went down upon the enemy with a wild shout, the two wings were brought into one line again. I directed the whole Regiment to take intervals at 5 paces by the left flank, & change direction to the right, all this without checking our speed, thus keeping my right connected with the 83rd Penna, while the left swept around to the distance of half a mile. In this charge the bayonet only was used on our part, & the rebels seemed so petrified with astonishment that their front line scarcely offered to run or to fire—they threw down their arms & begged “not to be killed”, & we captured them by whole companies. We took in this charge 368 prisoners, among them a Colonel, Lieut. Col. & a dozen other officers who were known. I had no time to inquire the rank of the prisoners, but sent them at once to the rear. The prisoners were amazed & chagrinned [sic] to see the smallness of our numbers, for there were only one hundred & ninety eight men who made this charge, & the prisoners admitted that they had a full Brigade.

I reported at once to Col. Rice, who immediately came up, & who with the greatest promptitude brought up a Brigade as a support, & a supply of ammunition. We then threw up a small breastwork of rocks, & began to gather up the wounded of both parties. 21 of my men lay dead on the field, & more than 100 wounded. 50 of the enemy dead were counted in our front, their wounded we could not count. What is most surprising is that often as our line was forced back & even pierced by the enemy, not one of my men was taken prisoner, & not one was “missing”. It was now nearly dark, & Col. Rice ordered me to take the high & difficult hill on the left of our general line of battle, (but more nearly in front of my own line) where the enemy appeared to have taken refuge…. My men were exhausted with toil & thirst, & had fallen asleep, many of them, the moment the fighting was over, but the…little handful of men went up the hill with fixed bayonets, the enemy retiring before us, & giving only an occasional volley. Not wishing to disclose my numbers, & in order to avoid if possible bringing on an engagement in which we should certainly have been overpowered, I went on silently with only the bayonet. We carried the hill, taking twenty five prisoners, including some of the staff of Gen. Laws commdg the Brigade. From these I learned that Hoods Division was massed in a ravine two or three hundred yards in front of me, & that he had sent them out to ascertain our numbers, preparatory to taking possession of the hill with his Division. Fortunately I was able to secure all this party…so that Gen. Hood never received the reports of his scouts. My men stood in line that night, & received the volleys of the enemy without replying….In this movement I lost one officer mortally wounded, & one man taken prisoner in the darkness. The prisoners in all amounted to 393 who were known; 300 stand of arms were taken from the enemy. We went into the fight with 380 officers & men, cooks & pioneers & even musicians fighting in the ranks, my total loss was 136 as more fully appears in the tabular report already sent you.

We were engaged with Laws’ Brigade, of Hood’s Division, Longstreets Corps,—the 15th & 47th Alabama 4th & 5th Texas: our prisoners were from all these Regts….

This article was originally published in the June 2012 issue of Civil War Times.