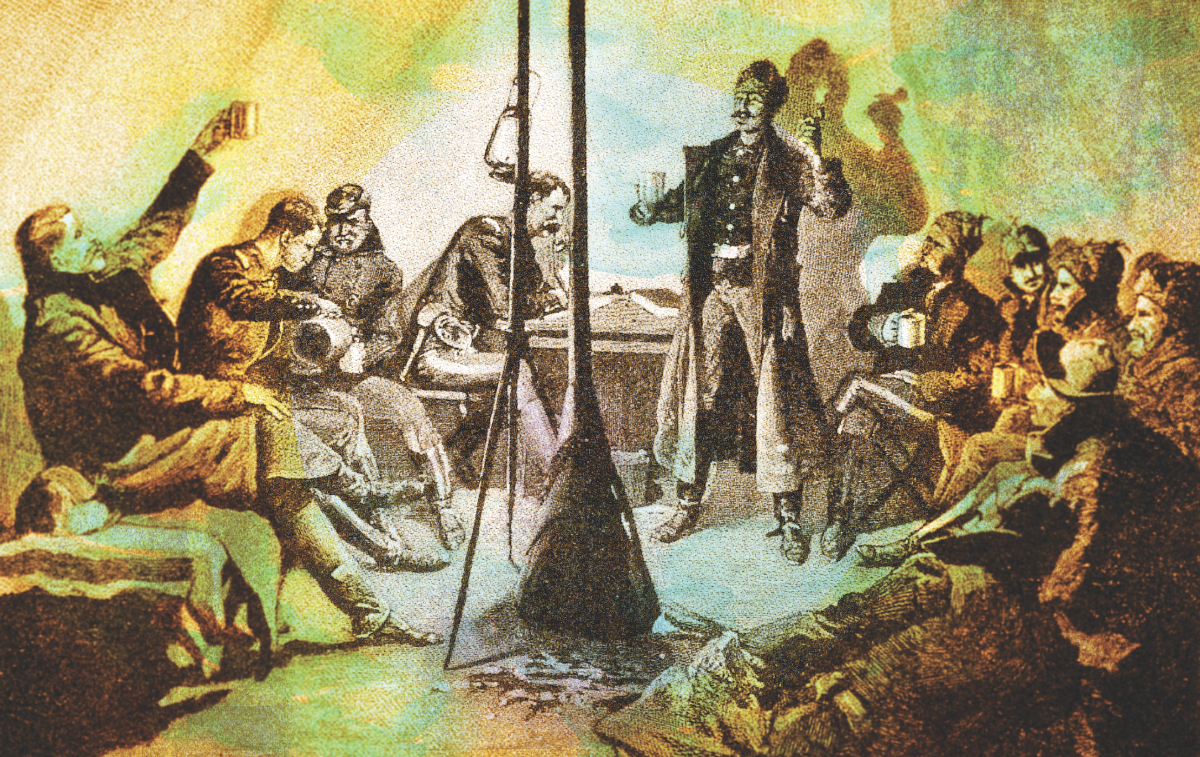

In his 1895 book Pony Tracks artist and writer Frederic Remington, who knew the pony soldier as well as anyone, captured the essence of a frontier cavalry trooper’s Christmas away from home: “Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we may die.”

Not a good excuse, but it has been sufficient on many occasions to be true. The soldier on campaign passes life easily. He holds it in no strong grip, and the Merry Christmas evening is as liable to be spent in the saddle in fierce contact with the blizzard as in his cozy tepee with his comrades and scant cheer.

The jug containing the spirits of the occasion may have been gotten from a town 50 miles away on the railroad.…It is never a late evening, such a one as this; it’s just a few stolen moments from the “demnition grind.” The last arrival may be a youngster just in from patrol, who explains that he just “cut the trail of 40 or 50 Sioux 5 miles below, on the crossing of the White River”; and you may hear the bugle, and the bugle may blow quick and often, and if the bugle does mingle its notes with the howling of the blizzard, you will discover that the occasion is not one of merriment. But let us hope that it will not blow.

Remington’s description of a soldier’s Christmas Eve on the frozen Dakota prairie epitomizes the solitude and malaise encountered by countless men called away from home during the Indian wars. Soldiers in all wars, regardless of time and place, experience the unique loneliness common to men in uniform while on campaign.

But for soldiers on the American frontier the inability to reach out to loved ones, especially prior to the introduction of railroad connections and telegraph offices, added to the emotional toll. Even after technology caught up with them, contact with those back home was rare. Fortunately, period letters and reminiscences of Christmases past have left us a record that might not have existed had more modern communications been prevalent in the Old West.

Of course such records are more common among the papers and published memoirs of the privileged officer corps. In many instances officers’ wives, rather than their husbands, preserved such written memories. Especially striking are the recollections of those senior officers’ wives fortunate enough to have lived with their husbands in genteel, sometimes elaborate houses at frontier outposts, some of which remain standing or have been reconstructed. Letters and reminiscences of such memorable times lie scattered like gift wrap among the papers and books of Elizabeth Bacon Custer, wife of famed Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

CHRISTMAS ON THE FRONTIER

While it was not always possible for “Libbie” and her “Autie” to spend holidays together on the frontier, they made their own opportunities. When George first went west in 1865, for example, the couple spent Christmas together in Austin, Texas. “We had a lovely Christmas,” Libbie recalled. “Here we had little opportunity to buy anything, but I managed to get up some trifle for each of our circle. We had a large Christmas tree, and Autie was Santa Claus and handed down the presents, making sidesplitting remarks as each person walked up to receive his gift.

The tree was well lighted…the rooms were prettily trimmed with evergreens, and over one door a great branch of mistletoe, about which the officers sang.…Armstrong gave us a nice supper, all of his own getting up.” Libbie was positively ebullient, radiating love for the season and her beau. But a decade later, writing to George’s brother Tom from New York, she expressed very different thoughts about her husband’s holiday spirit: “Autie always finds the day somewhat of a bore and is glad when it is over.”

The memory points to trials the couple had endured in the interim.

With the Army Reorganization Act of 1866 Custer received the lieutenant colonelcy of the newly created 7th U.S. Cavalry, and that fall he and Libbie headed west to Fort Riley, Kan. That first year on the frontier was a tumultuous one for Col. Custer. His introduction to Indian warfare came with Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s ill-fated campaign against the Cheyennes.

Libbie waited for him at Fort Riley, but George’s concern for her welfare in the wake of a cholera epidemic then sweeping the Plains led him to desert his post and go to her, resulting in his court-martial and a yearlong suspension from duty without pay. The Custers spent the fall and winter mostly at Fort Leavenworth, returning home to Monroe, Mich., in June 1868.

A favorite pastime of Victorian-era Americans in snow country was sleighing. Sometime during this period George ordered a shiny red custom sleigh (see P. 51), perhaps for Christmas revelry with Libbie and brother Tom, and had it delivered to Fort Leavenworth. When Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan recalled Custer from Monroe in the fall of 1868 to lead the 7th Cavalry in what erupted into the Washita campaign, the Custers abandoned the sleigh at Fort Leavenworth, where it now serves as a highlight in the post museum.

There are no known photos of the Custers or anyone else riding in the Leavenworth sleigh, and Libbie’s recollection of that Kansas Christmas morning makes no mention of the sleigh, let alone any snow or hijinks. “It’s cold and my nose bleeds,” she wrote amid a litany of housekeeping chores.

BITTER COLD AND NO CHEER

In the wake of the November 1868 Battle of the Washita, 7th Cavalry troopers experienced one of the worst winters on record in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) in pursuit of Kiowas and Cheyennes. Soldiers huddled around the conical stoves in their Sibley tents toasting the holiday without much cheer.

Custer dispatched a Christmas letter via Fort Cobb to Libbie at Fort Riley. “Here we are,” he wrote, “after 12 days’ marching, through snow and an almost impassable country where sometimes we made only 8 miles a day, following an Indian trail.” Custer was at least fortunate to spend the holiday at rest. Major Andrew Wallace Evans, who led a third prong of Sheridan’s winter campaign in Indian Territory, was not as fortunate. His command engaged Kiowas and Comanches at the Battle of Soldier Spring on Christmas Day, a holiday meaningless to the Indian alliance (see “Christmas in Comanche Country,” by John Flood, in the April 2016 Wild West).

From 1873 to ’76 the Custers were posted to Fort Abraham Lincoln in the wilds of bleak Dakota Territory. Christmases there were mostly white, although the snow cover appears sparse in an 1875 photo of a sleigh outing with 7th Cavalry Captain Tom Custer at the reins and regimental adjutant Lieutenant William W. Cooke and Libbie’s friend Agnes Bates as passengers.

More than a decade after the June 1876 death of her husband at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in Montana Territory, Libbie penned a general recollection of “yuletide on the Plains.” Although she doesn’t specify a location, it is likely a composite memory of Christmases in Dakota Territory. It remains perhaps her most vivid reminiscence of the holiday:

Sometimes I think our Christmas on the frontier was a greater event to us than to anyone in the States. We all had to do so much to make it a success.…

One universal custom was for all of us to spend all the time we could together. All day long the officers were running in and out of every door; the “Wish you Merry Christmas” rang out over the parade ground after any man who was crossing to attend to some duty and had not shown up among us.

We usually had a sleigh ride and everyone sang and laughed as we sped over the country where there were no neighbors to be disturbed by our gaiety. If it was warm enough, there poured out of garrison a cavalcade vehemently talking, gesticulating, laughing or humming bars of Christmas carols remembered from childhood, or starting some wild college or convivial chorus where everybody announced that they “wouldn’t go home till morning” in notes very emphatic if not entirely musical.

The feast of the day over, we adjourned from dinner to play some games of our childhood in order to make the States and our homes seem a little nearer. Later in the evening, when the music came up from the band quarters, everyone came to the house of the commanding officer to dance.

With a garrison full of perfectly healthful people with a determination to be merry, notwithstanding the isolated life and utterly dreary surroundings, the holidays were made something to look forward to the whole year round.

Despite the melancholia of her widowhood, Libbie Custer continued to cherish and celebrate Christmas until her own death in April 1933. Living in a modest apartment in New York, wintering in Florida and often visiting hometown Monroe, she spent much of her idle time in the company of such friends as Annie Yates, widow of Captain George Yates, who was also killed at the Little Bighorn.

lonely LIFE AS A WIDOW

But Libbie had little idle time, as she spent a productive life defending her husband’s image in books and many articles. She also wrote of Christmas. In a piece published in the December 1890 Ladies’ Home Journal, Libbie expressed a nostalgic Christmas sentiment that reflected the loneliness of 14 years spent without her Autie:

“I dearly wish that I might enter your comfortable homes and hear of your aims, your blessings and perplexities, your sorrows. In wishing all the good things this world gives may descend on the households to which the Journal goes, I would that it might give me the special privilege to let me enter those thousands of little makeshifts for homes throughout our land that the busy women of limited means have set up; the dingy rooms under the eaves, where deft fingers have made such transformations; the little apartments where is ever semi-twilight, where God’s beautiful twilight comes in through the narrow windows—ah, it is to you, brave but lonely women, if any such read these words, that I wish to send my love, and whatever of courage deep felt words can convey. The widows, the girl bachelors, the solitary old maids, all of you who are so much to me, I envy the printed and pictured sheets of this holiday Journal, the cheer and comfort they carry.”

As the Custers prepared for their first Western Christmas in Texas, a very different sort of yuletide was playing out for the isolated garrison at Fort Phil Kearny, in the far reaches of Dakota Territory (in present-day Wyoming). Outside its log stockade on Dec. 21, 1866, a well-organized force of more than 1,000 Plains Indians—mostly Oglala and Minneconjou Lakotas, joined by Brulés, Northern Cheyennes and Arapahos—wiped out a detachment comprising 49 soldiers of Companies A, C, E and H of the 18th U.S. Infantry, 27 troopers from Company C of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry and two civilians.

Killed alongside their men were commanding officer Captain William J. Fetterman, Captain Frederick H. Brown and 2nd Lt. George Washington Grummond. The Indians had decoyed the troops over Lodge Trail Ridge overlooking the fort. The annihilation of Fetterman’s 81-man command was the worst defeat for the U.S. Army on the Plains to that date, exceeded only by Custer’s defeat a decade later.

About 7 p.m. on December 21 post commander Col. Henry B. Carrington contracted two civilians, John “Portugee” Phillips and Daniel Dixon, to carry news of the Fetterman disaster to the nearest telegraph station and then continue to Fort Laramie for reinforcements—a 236-mile ride (see related story, P. 58). When Phillips arrived at Fort Laramie that snowy Christmas night, a guard took him to see Brevet Maj. Gen. Innis N. Palmer, who was attending a dress ball at “Old Bedlam,” the bachelor officers’ quarters turned post headquarters (today the oldest extant building in Wyoming). Captain David Gordon of the 2nd Cavalry, stationed at Fort Laramie, recalled the episode:

It was on Christmas night, 11 p.m.…when a full-dress garrison ball was progressing, and everybody appeared superlatively happy, enjoying the dance, notwithstanding the snow was from 10 to 15 inches deep on the level, and the thermometer indicated 25 degrees below zero, when a huge form dressed in buffalo overcoat, pants, gauntlets and cap, accompanied by an orderly, desired to see the commanding officer.

RIDER FROM FORT PHIL KEARNY

The dress of the man, and at this hour looking for the commanding officer, made a deep impression upon the officers and others that happened to get a glimpse of him and consequently, and naturally too, excited their curiosity as to his mission in this strange garb, dropping into our full-dress garrison ball at this unseasonable hour.

On that bitter cold and snowy Christmas, as Phillips rode into Fort Laramie, anguish still gripped the garrison at Fort Phil Kearny. No one knew if either rider had made it through or succumbed to the elements—or Indians. The holiday only served to amplify their melancholy and grief. Carrington’s wife, Margaret, later wrote:

The holidays were sad as they were cold.…The constant and drifting snowstorms soon so lifted their crests by the west flank of the stockade that officers walked over its trunks.…The men themselves, who, at the October muster, looked forward to the holidays and December muster with glad anticipations, forbore all demonstrations usual to such a period and sensibly felt the weight of the great loss incurred.…The whole garrison shared the gloom.

Charades, tableaus, Shakespearian readings, the usual muster evening levee at the colonel’s and all the social reunions which had been anticipated as bringing something pleasant, and in the similitude of civilized life, were dropped as unseasonable and almost unholy.

Margaret noted that details from each company spent the days leading up to Christmas respectfully preparing the horrifically mutilated bodies, which Colonel Carrington hoped to bury in a solemn Christmas Day service (it actually took place on December 26). The men extracted or cut off arrows and reassembled body parts as best they could, and some donated their best uniforms to dead comrades for interment.

According to Margaret, the deceased were placed in numbered boxes and arranged in lines by companies along officers’ row. The burial details placed two enlisted men to a coffin, while the three officers had separate caskets. Clerks recorded names and corresponding coffin numbers for future reference. Given the magnitude of the mutilations inflicted by the American Indians, it is hard to imagine the coffins were open for viewing. If they were, Capt. Brown’s corpse would have presented a particularly gruesome spectacle.

Almost a half-century later Pvt. William R. Curtis, one of the men who had helped prepare Brown’s frozen body for burial, described the awful sight to Indian wars historian Walter Mason Camp. “The privates of Captain Brown were severed and placed in his mouth,” Curtis recalled, “and considering the extreme cold weather, they could not be extricated.” The soldiers buried Brown in this unfortunate repose. The garrison survived the hard winter, but the War Department ordered the post abandoned in 1868 as part of the second Treaty of Fort Laramie, and Cheyennes subsequently burned it to the ground.

Twenty-four years after that disconsolate Christmas at Fort Phil Kearny, a bugler on the South Dakota plains sounded “Boots and Saddles” for the men of the 6th U.S. Cavalry, then seeking to intercept a band of recalcitrant Lakota “Ghost Dancers” under Chief Big Foot (aka Spotted Elk) near the White River.

CHASING GHOST DANCERS

For well over a decade the proud but defeated Lakotas had been confined to a reservation as indigent wards of the federal government. Facing the extinction of their culture, they had recently placed their hopes in a self-proclaimed prophet named Wovoka, a Paiute medicine man who preached the gospel of the Ghost Dance, a practice he claimed would resurrect their ancestors, drive away the whites and restore their traditional way of life.

Alarmed at the rapid spread of this disruptive and potentially violent movement, the Army took steps to suppress it. Sixth Cavalry Col. Eugene Asa Carr’s Dec. 24 patrol represented the tip of the spear. That evening on Sage Creek his bivouacked troopers spent a cheerless Christmas Eve tending fires and trying to sleep beneath their thin wool saddle blankets. The Lakotas eluded Carr, but by Dec. 26 Custer’s old 7th Cavalry, then under Major James W. Forsyth, had taken the field with orders to disarm Big Foot’s Ghost Dancers and take them to the nearby Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

Troopers intercepted the band of nearly 400 Lakotas on December 28 and escorted them to Wounded Knee Creek. When Forsyth’s men moved to disarm their captives the next morning, a shot rang out, sparking an exchange of gunfire. Big Foot, prostrate with pneumonia, was killed immediately. Within minutes the skirmish turned into a slaughter as vengeful troopers and four rapid-fire Hotchkiss rifled guns rained death on half of Big Foot’s band—some 200 men, women and children. Soldiers transported the wounded to a church at Pine Ridge still decorated with Christmas garlands.

In the end perhaps Remington best summed up the collective joys, miseries, tribulations and horrors experienced by the frontier Army at Christmastime. If you were a soldier on the Western Plains, pondering your mortality, another Christmas gone, this was what it was like: “You stumble through the snow-laden willows and face the cutting blast, while the clash and ‘Halt!’ of the sentinel stop you here and there. You pull off your boots and crawl into your blankets quickly before the infernal Sibley stove gives its sigh as the last departing spark goes up the chimney and leaves the winds and drifting snows to bellow and scream over the wild wastes.” WW

John H. Monnett, emeritus professor of history at Metropolitan State University of Denver, has written or contributed to more than a dozen books on the history of the American West and is a frequent contributor to Wild West. Suggested for further reading are his Rocky Mountain Christmas: Yuletide Stories of the West and A Frontier Army Christmas, by Lori A. Cox-Paul and Dr. James W. Wengart. Also see “Christmas Frontier-Style,” by Gregory Lalire, in the December 2007 Wild West.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.