‘They watched her closely, counting her words, but Fanny outfoxed them by combining words, enabling her to inform the wagon train of her plight’

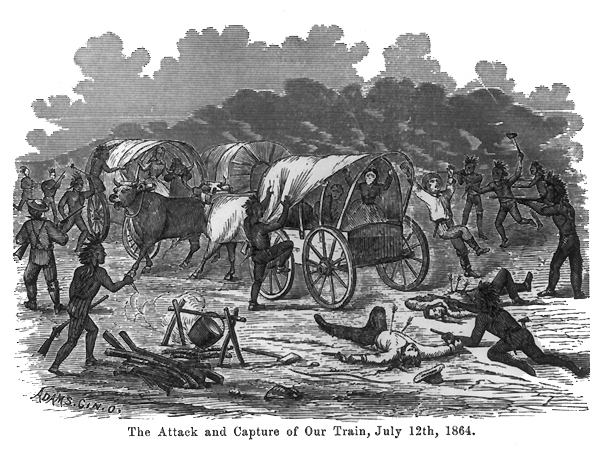

Josiah Kelly and Andy, a black hired hand, watched helplessly from their hiding place where they had been gathering wood as Oglala Sioux (Lakota) warriors murdered three members of their wagon train and took four others captive on July 12, 1864. Josiah, his 19-year-old wife Fanny, Fanny’s 7-year-old niece Mary Hurley and hired men Andy and Franklin had joined a train of five wagons heading to the Montana Territory goldfields. Josiah’s health was poor, and he and Fanny thought it might improve if they headed west to seek their fortune. The trip from their home in Geneva, Kansas, had been typical of westward emigrants at the time—hard travel, but also some pleasant experiences—until they neared Little Box Elder Creek, about 14 miles west of present-day Douglas, Wyoming. As they crossed the creek that late afternoon, more than 200 Oglala warriors rode up to the wagons.

At first the visitors seemed friendly. When they requested gifts, Josiah and the others willingly gave them items, including Josiah’s prized thoroughbred. The warriors, seemingly content, urged the emigrants to move on and steered them toward an ominous looking rocky glen. When the emigrants balked, the Oglalas insisted they make supper for the warriors. While the travelers were preparing camp, the warriors fired on them without warning, instantly killing Franklin, Noah Taylor and a Methodist minister named Sharp. William Larimer and Gardner Wakefield were seriously injured, but escaped. The warriors ransacked the wagons and rode off with Fanny and the only other woman, Sarah Larimer, as well as the two children—Mary Hurley and Sarah’s 8-year-old son, Frank. That night Sarah and Frank successfully escaped the Oglalas. Fanny helped Mary escape, but the girl wasn’t as lucky as the Larimers. Her captors tracked her down. A search party that included Josiah Kelly later found Mary, scalped, with three arrows protruding from her back. There was no sign of Fanny.

But Fanny Kelly did not disappear from the historical record. Amazingly, two months later in what would become North Dakota, she appeared again. Captive Mrs. Kelly found herself part of a highly dramatic trail incident in which another emigrant wagon train party fell under attack, cobbled together a fortification dubbed “Fort Dilts” and held out under siege as they waited more than two weeks for help.

Three days after Fanny Kelly’s capture and 700 miles to the east, 29-year-old Captain James Liberty Fisk of the U.S. Quartermaster Corps led a civilian wagon train out of Fort Ridgely, Minn., westbound for the Montana goldfields. The party comprised 170 men, women and children in 97 wagons pulled by mules and oxen. Fisk had led wagon trains to the Montana goldfields twice before, but during a more peaceful time in Dakota Territory, before armies led by Generals Henry Sibley and Alfred Sully battled the Dakota and Lakota Sioux and inflamed the countryside. Fisk’s July 1864 train would have to pass through hostile territory.

In 1862, due to the insensitivity of Indian agents and a scarcity of promised food and supplies, the Dakotas were beginning to starve. After some of the frustrated young men murdered several white farmers, the tribe rose in support and killed hundreds of Minnesota settlers. The Army retaliated for this Sioux uprising, fighting and chasing the renegades into Dakota Territory, where the Dakotas joined forces with their sympathetic Lakota relatives. Generals Sully and Sibley were operating in Dakota Territory against them, building forts and attempting to defeat them. By 1864 it was a mighty unfriendly region.

The federal government had commissioned Fisk—captain and assistant quartermaster, commanding the North Overland Expedition—to protect the wagon trains headed for the goldfields. The Union sought to boost the gold mining industry to help finance its war effort.

Near Minnesota’s western border in eastern Dakota Territory, Major John Clowney’s encamped troops were building Fort Wadsworth (later Fort Sisseton). On reaching the camp, Fisk asked Clowney for an escort. Clowney assigned 50 men commanded by Lieutenant Henry F. Phillips to accompany the wagon train as far as Fort Rice, then under construction on the Missouri River. There Fisk expected to join General Sully’s expedition, remaining with it until reaching the Yellowstone River, where they would part company. Fisk reasoned at that point the wagon train would be out of Sioux territory, and it would be relatively safe to continue to the goldfields.

The wagon train reached Fort Rice in mid-August with little mishap. On arrival Fisk became upset when he learned that Sully had left on his campaign without him and, worst still, was escorting a competitor’s wagon train. Fisk tried to order Phillips to escort them to the Yellowstone, but the lieutenant followed his orders to return to Fort Wadsworth.

Undeterred, Fisk asked Colonel Daniel J. Dill, commander of Fort Rice, for an escort. At first Dill told Fisk he could not spare any troops. But after listening to Fisk’s arguments, he reluctantly agreed to provide an escort of men Sully had left behind to recover from sickness and injury. Dill had asked for 50 volunteers and got 45. Sully had left behind a number of horses that were also in poor condition, and the volunteers chose the fittest of these as their mounts. Second Lieutenant Dewitt C. Smith, who was awaiting the decision of a court-martial against him, would command them. Smith’s orders were to accompany the emigrants only as far as the Yellowstone and then return to the fort. Second in command was Sergeant Willoughby Wells of Brackett’s Battalion, Company B; he and his guard detail had just arrived with a steamboat loaded with supplies for the fort. Fisk had obtained a 12-pounder mountain howitzer from Fort Snelling, Minn., with a limited supply of canister and powder. With the escort, howitzer and armed men of the wagon train, Fisk believed he had enough firepower to withstand a Sioux attack. The wagon train and its escort headed westward from Fort Rice on August 23. During the first night on the trail five of the volunteers had a change of heart and returned to the fort.

Sully’s army had marched west pursuing hostile Lakota and Dakota tribes. Fisk followed their trail about 80 miles west of Fort Rice until it swung north, not the direction he wanted to head. He determined to blaze a new, shorter trail through unknown territory, due west between the Black Hills to the south and the Little Missouri River badlands to the north.

Every Sunday was a day of rest for humans and beasts. Fisk arranged shooting matches each Sunday. The second Sunday out from Fort Rice, Fisk held a contest between the best civilian shot in the wagon train and the top marksman from among the soldiers for a $10 prize. Sergeant Wells won and used his money to buy tobacco for the troops from one of the emigrant storekeepers.

In late afternoon on September 2, some 180 miles west of Fort Rice, one of the wagons upset while trying to cross Deep Creek. Fisk directed the wagon train to continue, leaving behind a second driver with his wagon and a rearguard, 12 men altogether, to right the wagon, fix it and then rejoin the rest of the train.

Within minutes more than 100 Hunkpapa Sioux attacked the two wagons and rearguard, cutting them off from the rest of the wagon train. Gall and Sitting Bull, who would later both become famous, participated. Two warriors teamed up against Corporal Thomas Williamson of the 6th Iowa Cavalry, beating him with their clubs and stabbing him with their knives. Williamson fought them off in hand-to-hand combat, but then Sitting Bull rode up and shot an arrow into the corporal’s back. Williamson turned and fired his pistol at Sitting Bull, hitting him in the hip and knocking him out of the fight. Despite his many wounds, Williamson mounted his horse and returned to the wagon train, reporting to Fisk on the situation. Williamson later died from his wounds. The Hunkpapas killed the rest of the rearguard and ransacked the two wagons.

Fisk and the wagon train were about a mile beyond the creek crossing when hey heard the shooting. Sergeant Wells was ahead of the wagons with an advance party when he saw in the distance Hunkpapas surrounding the rearguard and two wagons. Wells and his men galloped their horses back to protect the rear of the train from attack. Jefferson Dilts, a scout and former Army corporal, urged his horse far ahead of the rescue party to reach the rearguard. Dilts shot down some half-dozen warriors, but as he finally turned to retreat, three arrows struck him in the back. (The brave scout would travel on with the Fisk wagon train but would die from his wounds after 16 days of agony.) Undeterred, the Hunkpapas continued to ransack the wagons, taking new Sharps carbines, thousands of rounds of ammunition, liquor, cigars, canned goods, stationery, silverware and other valuables. After two hours of fighting the rescue party temporarily drove off the Hunkpapa attackers and had enough time to recover the bodies for later burial.

As the wagon train continued west, the Hunkpapas harassed it. The emigrants soon found a good defensive position between two ridges with a bowl-shaped depression in which they could corral the animals. Here they made camp for the night. The warriors sporadically shot their new firearms into the camp, but fortunately for the emigrants, the Hunkpapas were not very accurate with them—yet. The besieged party did not light fires that night. But they did make time to bury their fellow travelers who had been killed that day. Wolves outside camp howled at the scent of blood and death. Adding to the misery, a violent thunderstorm struck.

September 3 dawned to reveal the emigrants’ cattle standing in 2 feet of frigid water. The wagon train resumed its journey, while the Hunkpapas continued their long-distance harassment by shooting at people and animals. They managed to kill several oxen and horses. The emigrants made camp after a nine-mile advance. When a large number of Hunkpapas gathered for a massed attack, the soldiers loaded the howitzer and fired a shot of canister at them. After that they kept their distance but continued to mill around and fire at the emigrants. They did not attack the camp that night.

The next morning some of the emigrants, without Fisk’s knowledge and with the Minnesota massacres still fresh in their minds, left behind a box of strychnine-laced hardtack for the Indians to find. Just how many Hunkpapas died from eating the poisoned hardtack is unknown, but according to one account, by the end of the campaign “more had died from eating bad bread than from bullets.”

The Hunkpapas stepped up their attacks on the wagon train. Lieutenant Smith believed the warriors were again forming to make a massed attack, so after progressing only a few miles, the emigrants stopped at a good defensive position near water. As they were circling the wagons, unhitching the livestock and bringing them into the wagon corral, the warriors advanced close enough to shoot arrows into the enclosure. One Hunkpapa leader, a good rifle shot, ventured a bit too close and was shot and killed. That prompted the other warriors to withdraw, though they remained within sight of the train. The emigrants were elated at the turn of events. A would-be saloonkeeper by the name of McCarthy toted around a bucket of whiskey and tin cup and served a drink to whoever wanted to celebrate with him, until Fisk put a halt to it.

The Hunkpapa warriors still meant business. Their number had increased to at least 300 warriors, and they were closing in on all sides. Fisk realized his group would not be able to move ahead or, indeed, get out of this situation without help. Lieutenant Smith and 14 men volunteered to try to break through Hunkpapa lines and ride the nearly 200 miles back to Fort Rice for a rescue party. They selected the fittest horses, muffling their hooves, and left the defensive enclosure that night during a storm. The Hunkpapas did not discover their escape until the next morning when they spotted the horses’ tracks. A large group of warriors sped after the troopers, hoping to overtake them before they reached Fort Rice.

Resolved to fortify their position, the emigrants unpacked plows, hitched oxen to them and plowed up prairie sod to erect an encircling wall. When finished it was 2 feet thick and 6 feet high with rifle pits and loopholes from which to shoot at attackers. They named their sod fortification Fort Dilts after mortally wounded scout Jefferson Dilts.

Later that September 5 three Hunkpapa riders rode toward the fort bearing a white flag on a makeshift staff. The emigrants held their fire as the trio planted the flag between the two groups. Once the riders had returned to the main body of Hunkpapas, Fisk sent a detail out to investigate. Beside the flag, stuck in the ground, they found a message wedged in a forked stick.

Written in English, the message demanded that all the emigrants immediately depart Hunkpapa territory and leave behind wagons loaded with goods in tribute. But the message said far more than that. It also said that Fanny Kelly had written the note and was being held captive. She pleaded with them to rescue her.

Indeed it was Fanny Kelly who had scribbled the note. Sometime after taking her captive that July, the Oglalas had traded her to the Hunkpapas. Some of the Hunkpapas could speak English, but none could write it, so they told Fanny what to write and warned her not to add anything. They watched her closely, counting her words, but Fanny outfoxed them by combining words, enabling her to inform the wagon train of her plight.

Fisk did not trust the note. He wrote back, telling Fanny to show herself. She did so, standing atop a nearby bluff, and the men at Fort Dilts spotted her through a spyglass. Appreciating the risk she had taken, Fisk negotiated two days for her release, including driving out a wagonload of goods between the hostile camps. But the Hunkpapas demanded too high a ransom, and in any case Fisk and the others did not trust them to actually release Fanny.

Meanwhile, Smith and his men were riding hard. At one point they lost the trail but later regained it, only to discover that the pursuing Hunkpapa war party was on the trail—ahead of them. Fortunately for Smith and his men, the war party never discovered the troopers. Believing Smith and his men had already reached Fort Rice, the war party eventually broke off and rejoined the main Hunkpapa band, still harassing the emigrants at makeshift Fort Dilts. Smith and his exhausted troopers reached Fort Rice after three days.

General Sully had just returned from his campaign against the Sioux, having fought them at the Battle of Killdeer Mountain on July 28 and the Battle of the Badlands on August 7–9. He was furious Fisk had proceeded for Montana Territory with such a small escort. Sully would now have to mount a rescue operation. He ordered Colonel Dill to lead a 900-man relief expedition. By the time Dill reached Fort Dilts on September 20, the Hunkpapas were gone. They had grown weary of sniping at the fort and left to hunt buffalo.

Fisk requested an onward escort to the goldfields. Dill told the emigrants they could return with him to Fort Rice but would be on their own if they continued west. Fisk couldn’t win this argument, and he and the other emigrants bid their stout little sod fort farewell and returned to Fort Rice with Dill. The 1864 expedition disbanded, but Fisk persevered and would lead a fourth emigrant group west in 1866.

Meanwhile, the news was out about Fanny Kelly. The military let it be known among friendly Hunkpapa contacts it wanted the captive woman returned and would give presents to whoever returned her to Fort Sully, near present-day Pierre, S.D. On December 12, 1864, three months after the Fort Dilts fight, Hunkpapas arrived at Fort Sully with Kelly. Some of the Indians claimed they had negotiated Fanny’s release and brought her to the fort out of friendship and for the presents the military had offered for her safe return. Kelly believed the Indians intended to use her return as a ruse to get a large number of warriors into the fort to take it over. She apparently was able to persuade Jumping Bear, a Hunkpapa friend, to get word to Major Alfred E. House, Fort Sully’s commander, about the ruse.

When more than 1,000 Hunkpapas showed up with their captive, Major House allowed just 10 chiefs into the stockade with Fanny and then ordered the gates closed. “In my opinion, had the Indians attacked the fort, they could have captured it,” recalled 1st Lt. Gustav A. Hesselberger. Fanny was free. Husband Josiah was informed of her rescue and joined Fanny as soon as he could. In later years Fanny wrote a memoir of her ordeal, Narrative of My Captivity Among the Sioux Indians, which remains in print.

Fort Dilts is not forgotten. The sod wall, wagon ruts and graves are preserved within Fort Dilts State Historic Site, eight miles northwest of Rhame, N.D. A site marker, interpretive sign, flagpole, registration box and barbed wire fence are modern, but the fort made out of desperation looks much as it did 150 years ago.

Bill Markley, who lives in Pierre, S.D., has written for Wild West and is a member of Western Writers of America. Suggested for further reading: Narrative of My Captivity Among the Sioux Indians, by Fanny Kelly; Terrible Justice, by Doreen Chaky; and The Dakota War, by Michael Clodfelter.