On Friday, October 26, 1962, one day before “Black Saturday,” the most terrifying day of the Cuban Missile Crisis, CIA Director John McCone gave President John F. Kennedy more bad news about the Soviet military build-up on the island. He explained that the Soviets were spending an estimated $1 billion on their military installations and that “rapid construction activity” was continuing. More alarming was the discovery of a Soviet FROG-7 missile launch system (also referred to as a Luna-M), a tactical nuclear weapon that could be used against an American invasion or the U.S. outpost at Guantanamo Bay.

This information prompted Strategic Air Command (SAC) to authorize a Lockheed U-2 reconnaissance flight over Cuba for October 27. U.S. Air Force U-2s and Navy Vought RF-8 Crusaders had been used extensively in the prior days to photograph medium-range ballistic missile sites, SA-2 surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites and a variety of Soviet military installations and troop barracks. While the Crusaders were used for the low-level surveillance and close-up photographs, the high-flying U-2s could cover a much broader area with their high-resolution cameras.

With its 103-foot wingspan and lightweight frame, the U-2 looks something like a sailplane on steroids. It can fly so high—73,000 feet—that the pilot must don a specialized pressure suit and fishbowl-style helmet, similar to what astronauts wear. Should the single-seat cockpit lose air pressure, the suit is designed to inflate and keep the pilot alive. Otherwise in the thin air of the stratosphere the pilot’s blood would literally begin to boil.

While the U-2’s cruising altitude put it safely beyond reach of Soviet MiG fighters, the spyplane was vulnerable to SAMs. Francis Gary Powers had been shot down in his U-2 just two years before the Cuban crisis. Consequently, President Kennedy and his military advisers were well aware of this risk, and they had agreed upon a course of action should a U-2 be shot down over Cuba. Kennedy secretly recorded all of his Cabinet Room meetings during the crisis, and on the tape recordings Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara gave his opinion on the subject: “We are maintaining aircraft on alert that have the capability, if you decide to instruct us to do so, to go in and shoot the SAM site that shot down the U-2. We would recommend that we send eight aircraft out to destroy the site, and have it destroyed within two hours of the time the U-2 itself was struck.”

The president agreed and added details to the strategy, saying, “[W]hen we take out the SAM site we announce that if any [other] U-2 is shot down, we’ll take out every SAM site.” This agreement brought a measure of satisfaction to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who had been clamoring for a more robust military response to the Soviet build-up on the island than the naval quarantine that Kennedy had earlier implemented. The naval blockade would stop new equipment from arriving in Cuba, but would do nothing to curtail ongoing work to bring the nuclear missiles on the island to operational status. U.S. military leaders advocated a massive series of airstrikes followed by an invasion, and continued reconnaissance was essential for success.

On Saturday, October 27, SAC flight planners decided to send a U-2 to photograph the eastern part of the island. Major Rudolf Anderson Jr., stationed at McCoy Air Force Base in Orlando, Fla., was ready. The night before, he had asked operations manager Tony Martinez to put him on standby in case a pilot was needed the next day.

Once in the cockpit of his U-2, Rudy Anderson and a technician went through several checks, followed by more checks from Captain Roger Herman, who found everything in order and cleared him for launch. Herman slapped the pilot on the shoulder and said, “Okay, Rudy, here we go, have a good trip. See you when you get back.”

Anderson responded with a thumbs-up, and Herman closed the canopy. The pilot had taped two photos above his control panel: one of his smiling wife, the other of his two boys. Staring at the photos, he must have truly believed that his mission could save their lives and those of millions more around the world.

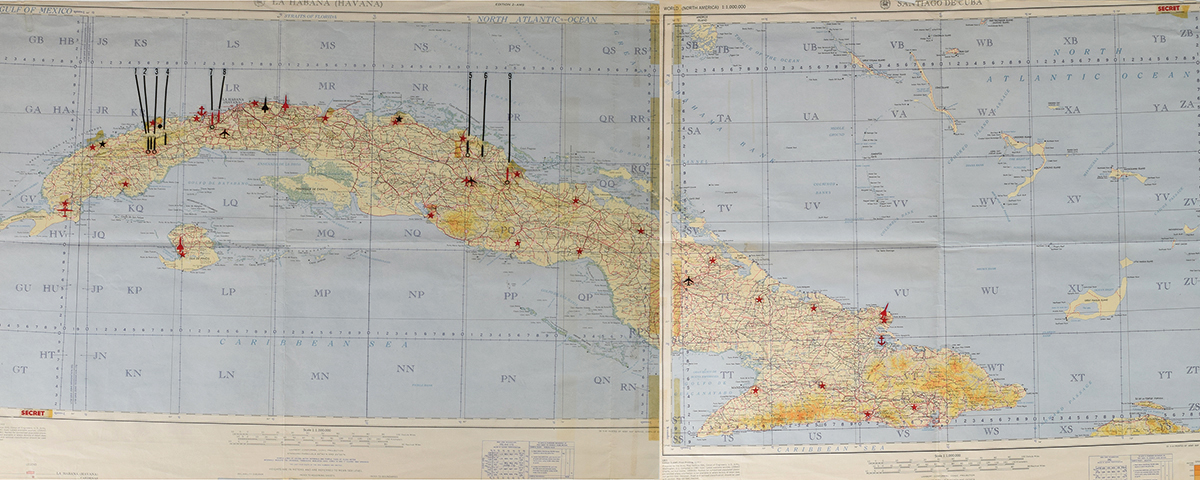

Leaving McCoy AFB at 9:10 a.m., Anderson enjoyed relatively clear skies. While he had performed five recon missions over Cuba during the crisis, none of the pilots who flew multiple missions viewed them as routine. His flight path would take him over the easternmost third of the island, coasting in from the north, initially in a straight line heading south-southeast. He would be passing within range of no less than eight SAM sites.

Recommended for you

Anderson flew at the usual 72,000 feet, first crossing over Cuba at the northern coastal islands of Caya Coco before continuing his trajectory over Esmeralda and Camagüey. So far so good. The weather was a mix of sun and clouds, the cameras were working fine and Anderson knew the extreme importance of the mission. His photos might reveal that warheads had been put on the missiles, indicating they were ready for firing. In 24 hours the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Kennedy himself would likely be examining some of his film to guide them in planning their next steps.

On the ground in Cuba, Soviet radar was tracking Anderson’s U-2, and the Russians labeled this intruding aircraft “target 33.” Nerves were frayed: Both the Soviets and the Cubans expected the United States to launch an all-out attack at any moment. And there was anger, too, particularly among the Cubans. Why let the Americans invade their airspace in the high-flying U-2s when they had the capability to shoot them down? Many of the Russians on the island agreed with their Cuban counterparts. After all, the Cubans and Russians toiling in Cuba—not those in Moscow—would pay the ultimate price if the U.S. attacked. They could not understand Moscow’s reluctance to let them defend themselves, but their orders were to withhold fire unless under attack. Some Soviet commanders on the ground thought this gave them a bit of leeway to use their judgment to shoot down the offending American planes if they sensed an attack coming during the overflights.

Monitoring target 33 were Soviet forces deputy commander Maj. Gen. Leonid Garbuz and deputy commander of air defenses Lt. Gen. Stepan Grechko, both stationed in a command center in Havana. “Our guest has been circling above us for more than an hour,” said Grechko. “I think we should give the order for downing the plane.”

The two generals decided to propose the action to General Issa Pliyev, who commanded all Soviet forces in Cuba. But a phone call to General Pliyev’s headquarters proved futile, as his aide-de-camp said he was unavailable. Pliyev, known to be ill with kidney disease, was possibly too sick to take the call.

Meanwhile Anderson flew over the town of Guantanamo, just north of the U.S. naval base there, his cameras recording Soviet military activity on the ground. This was an especially sensitive area, since it housed the troops and weapons, including the tactical nuclear missiles, that would be used to attack the naval base if the Americans launched an invasion.

Once past Guantanamo, Anderson made a slight turn to the east-northeast and continued to Jamal (just south of Baracoa). He was now close to the easternmost tip of Cuba. Over Jamal he made a wide U-turn (now heading west-northwest). By then Anderson had covered approximately 70 percent of his prearranged miles over Cuba.

At about this time Generals Garbuz and Grechko agreed they had the authority to decide whether to fire their SAMs. They believed an invasion was imminent, and the reports of large numbers of Crusaders buzzing the island, to which the Cubans responded with anti-aircraft fire, added to their apprehension. They were in communication with Colonel Grigory Danilevich at a command outpost in Camagüey, who also had target 33 on his radar screen. The two generals wanted to be sure the Camagüey men were tracking the same target on their monitor. Danilevich later said the anxiety was enormous, as was the uncertainty of action: “It [authorization for use of SAMs] was not a clear one. Where there is such great tension between two superpowers, why should there also not be confusion at the division level?”

The generals had watched target 33 come down from the north, turn toward the east and now make yet another turn that would take the U-2 over additional military installations before heading to safety over the ocean. The spyplane appeared as a light dot on a huge 5- by 10-meter screen, called a firing chart. As the dot moved across the screen, the two generals worried the plane would escape back to the U.S. with its intelligence. The men made another call to General Pliyev, but again he could not be located.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

If the two lower-ranking generals were to act, they must do so immediately. The men felt Pliyev would agree with them; the commanding general had repeatedly asked Moscow for permission to shoot down spyplanes, but had not received the go-ahead. Grechko announced, “Well, let’s take responsibility ourselves.”

The Russians at the Banes SAM site had their missiles trained on Anderson’s U-2. They were ready to fire, worried that if the orders did not come soon, the spyplane would be out of the targeting zone. Then over the radio came the command: “Target 33 is to be destroyed.”

Two SA-2s were launched, at least one of them by Lieutenant Alexy Raypenko, a member of the Soviet antiaircraft rocket unit. “A task is a task,” he later said, “and you have to do it well. I just happened to be at the end of the chain.”

One of the missiles exploded close enough to Anderson’s U-2 that shrapnel hit the aircraft and pierced his pressure suit. That would have caused decompression, and he likely died immediately. Anderson never had time to eject from the aircraft or hit the destruct switch, which would have blown the aircraft to pieces after a short delay to allow him to bail out.

When a U-2 has been damaged but not torn apart it pinwheels to the ground, like a leaf falling from a tree. This is what likely happened to Anderson’s plane, and as it spun toward the earth the tail and the wings were sheared off. The fuselage, still mostly intact, plummeted into the ground. Villagers and military personnel ran to the crash site. They found the smoldering ruins of the strange-looking aircraft, and inside the cockpit, still strapped to his seat, was the dead pilot.

Back in the U.S., SAC knew almost immediately that something was amiss with Anderson’s mission. SAC technicians could monitor the flight paths of their U-2s mile by mile, and when Anderson’s aircraft disappeared from the screen and he didn’t send the secret radio signal that all U-2 pilots routinely transmitted when leaving Cuban airspace, they knew with certainty that an accident or missile strike had forced the aircraft down.

Reconnaissance planes patrolling just off the island’s shore reported that they did not spot Anderson’s U-2 on their radar, nor did they see it crash. They searched the ocean but found no debris. Crusader pilots risked their lives flying directly over Banes in search of the downed spyplane. Some hoped that Anderson might have bailed out and was hiding in the jungle, ready to shoot off a flare if friendly aircraft appeared. But the Americans located neither the pilot nor the wreckage. SAC labeled Anderson missing in action, but almost no one held out hope that he had somehow parachuted safely to the ground. That fear was soon realized when Cuban radio stations began boasting of the shootdown of an American plane and the death of the pilot.

Air Force chief of staff General Curtis LeMay immediately ordered his North American F-100 fighter pilots at Homestead Air Force Base in Florida to be briefed and prepare for attack flights to Cuba. They carried Zuni air-to-ground rockets that could obliterate the SAM sites, killing both Soviet and Cuban defenders. Launch awaited only the president’s final approval.

Kennedy was informed of Anderson’s shootdown only after Cuban radio confirmed it, about three hours after SAC knew the U-2 was missing. In fact, it came up at a Cabinet Room meeting of the Executive Committee (Kennedy’s team to deal with the crisis) in an almost offhand way, after the meeting had been going on for some time. McNamara brought up the incident first, saying, “I think the rush is what we do. A U-2 was shot down.”

Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy was stunned, and spoke up first: “A U-2 was shot down? Was the pilot killed?’

McNamara answered yes. Then President Kennedy responded, almost in a subdued manner, saying “Well now, this is much of an escalation by them, isn’t it?”

After more discussion the president decided not to immediately strike back and destroy the offending SAM site as he had agreed to earlier. He wanted to give Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev one last chance to come to an agreement that would resolve the crisis. Most members of the Executive Committee disagreed and advocated retaliation. General LeMay, who was not at the meeting but quickly learned of the president’s decision, said in disgust, “He’s chickened out again. How in the hell do you get men to risk their lives when the SAMs are not attacked?”

Bobby Kennedy wrote that the despair and tension at the Executive Committee meeting that afternoon was palpable. “There was a feeling that the noose was tightening on all of us, on all Americans, on mankind, and the bridges to escape were crumbling.”

In an interview by this author with Sergei Khrushchev, Nikita Khrushchev’s son, he explained that the shootdown of Anderson had a profound effect on his father. The Soviet premier, like the U.S. president, feared that a single incident might cause the leaders to lose their grip on the situation. That event had now happened, and the two leaders had to come to an agreement before they lost control of events and the world hurtled toward nuclear Armageddon.

The key to the deal was Turkey, where the U.S. had nuclear missiles that Khrushchev wanted removed. JFK did not see this as an unreasonable demand, and in an evening meeting of the Executive Committee on Black Saturday he said as much: “We can’t very well invade Cuba with all the toil and blood it’s going to be, when we could have gotten them [the Soviet missiles] out by making the same deal in Turkey.” The president knew the missiles in Turkey were not essential to U.S. defenses, as nuclear-armed Polaris submarines off the Turkish coast could provide the same destructive force.

That night Bobby Kennedy relayed his brother’s proposal to the Soviet ambassador, essentially saying that if the Soviets removed their missiles from Cuba the U.S would promise not to invade the island, and in a very short time would remove the missiles from Turkey. The agreement could not be made public because of the potential political fallout for JFK and the need to inform both NATO and the Turks about the president’s plans.

Khrushchev knew this might be the last offer before military conflict engulfed Cuba, potentially leading to nuclear war between the two superpowers. His response to Kennedy’s offer was swift, and he did so publicly over Radio Moscow so as not to waste a single second. In an open letter to Kennedy, he announced the Soviet government’s intention to “dismantle the arms which you described as offensive, and to crate and return them to the Soviet Union.”

War had been avoided, but not before Major Rudy Anderson had paid the ultimate price. The Cubans released his body to the Swiss on November 5, and he was buried in his hometown of Greenville, S.C., the following day. In recognition of Anderson’s valor, President Kennedy posthumously awarded him the first Air Force Cross and the Air Force Distinguished Service Medal.

Michael Tougias is the co-author, with Casey Sherman, of Above & Beyond: John F. Kennedy and America’s Most Dangerous Spy Mission, from which this article is adapted. Visit michaeltougias.com for more info.

This feature appeared in the January 2019 issue of Aviation History. Click here to subscribe today!