[dropcap]J[/dropcap]ohn Marshall Branum knew about abolition and slavery in the South from an early age. His parents were both Swedenborgian, members of a Christian sect founded in the 18th century that followed the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, a theologian and philosopher known for his praise of the spiritual character of the African people. When the Civil War began, the 21-year-old Branum was enrolled at the Hopedale Normal School, a teachers’ college near his hometown of Bridgeport, Ohio. The school, which counted future Union icon George Armstrong Custer among its alumni, had been established by New England abolitionists in 1849.

Although Branum was certainly a committed—albeit not necessarily devout—Christian, there is no proof he ever considered himself an abolitionist. It is evident from his letters, however, that the wretched treatment of slaves across the South appalled him. Nevertheless, any condemnation he may have felt did not compel him to join the Union Army immediately when hostilities opened in April 1861.

Perhaps Branum, like so many of his comrades, was convinced the war would be short, a conviction of course quickly foiled on the battlefield by Confederate armies. But finally, in August 1862, the dire state of Union prospects after 15 blood-soaked months proved to be the tipping point, and Branum abandoned his studies and donned Federal blue. Scores of other young Northerners joined him in answering President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 300,000 new troops.

Bridgeport lay at the heart of the Ohio Valley. Across the Ohio River from “Old Virginia”—what would soon become the state of West Virginia—the region was a breeding ground of contending ideologies, from Republicans, abolitionists, and Lincoln-loving Wide Awakes to Democrats and even some peace-promoting Copperheads. Those groups, however, set aside their moral and political differences in the summer of 1862 and flocked to the Union cause. The area soon produced several regiments filled with eager young recruits.

Efforts to capture Richmond—and hasten the war’s end—had failed a few months earlier with the demise of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles. And for boys in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, a long-rumored Confederate invasion of Kentucky that now seemed imminent had spread further panic. Rebel Colonel John Hunt Morgan had also gone so far as to declare that his cavalry would soon “give Cincinnati a call.”

Upon joining the new 98th Ohio, Branum decided to preserve “the pen with which I wrote my name [and that] made me a soldier of the army.” He would use that pen to write a series of important letters during the conflict.

The 98th’s ideological divide showed not only in the ranks, but also in its commanders. Colonel George P. Webster, 37, a respected lawyer and Mexican War veteran, was a Democrat who had campaigned for Stephen A. Douglas for president in 1860; his second in command was Lt. Col. Christian L. Poorman, the 36-year-old editor of Ohio’s Belmont Chronicle, a Republican and an abolitionist. Both men had already seen action during the first year of the war.

When the 98th convened in early August at Camp Mingo, the site of an old Indian village in eastern Ohio, it was immediately apparent how different its volunteers were. One soldier described sitting at a campfire alongside men reading the Bible and singing church songs while others gambled or spouted obscenities (perhaps both).

Branum was among those from reasonably well-off, middle-class families, his father a successful local wholesale grocer. In those first few days, he would write, he felt “very much depressed…surrounded by strangers, many of them inferior to me in my former class and position, yet they all seemed, as it were, over me. What would my friends at home say, to see me keeping time with my left foot, at the bidding of some ‘Country Jake’?”

Within days, however, Branum fell into the rhythm of camp life, and began to enjoy the attention of civilians who flooded the camp. Children dashed through the columns of soldiers as they drilled; families sat watching in the shade trees; and young, unmarried women came out in droves.

Branum knew what lay ahead, however. “I was now starting out on a dangerous life,” he wrote, “and might well be forced to the cannon’s mouth.”

Further bad news had arrived from Kentucky. Confederate armies, headed by generals Edmund Kirby Smith and Braxton Bragg were threatening to converge in the Bluegrass State, while Union forces under Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell remained in Tennessee. Events would force the 98th Ohio to move out soon, with only a few weeks of training under its belt.

In late August the men boarded trains heading for the front. “Farmers were cutting their hay, and with the women and others waved their farewells, the boys cheering in return,” Branum wrote. He would refer to the men in his regiment as “brothers” for the first time. Never again would he write about their differences.

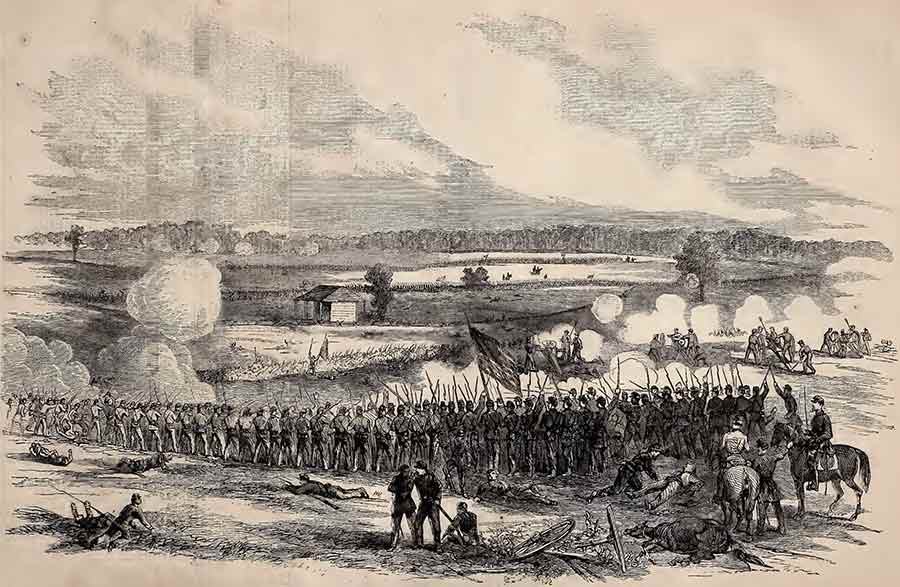

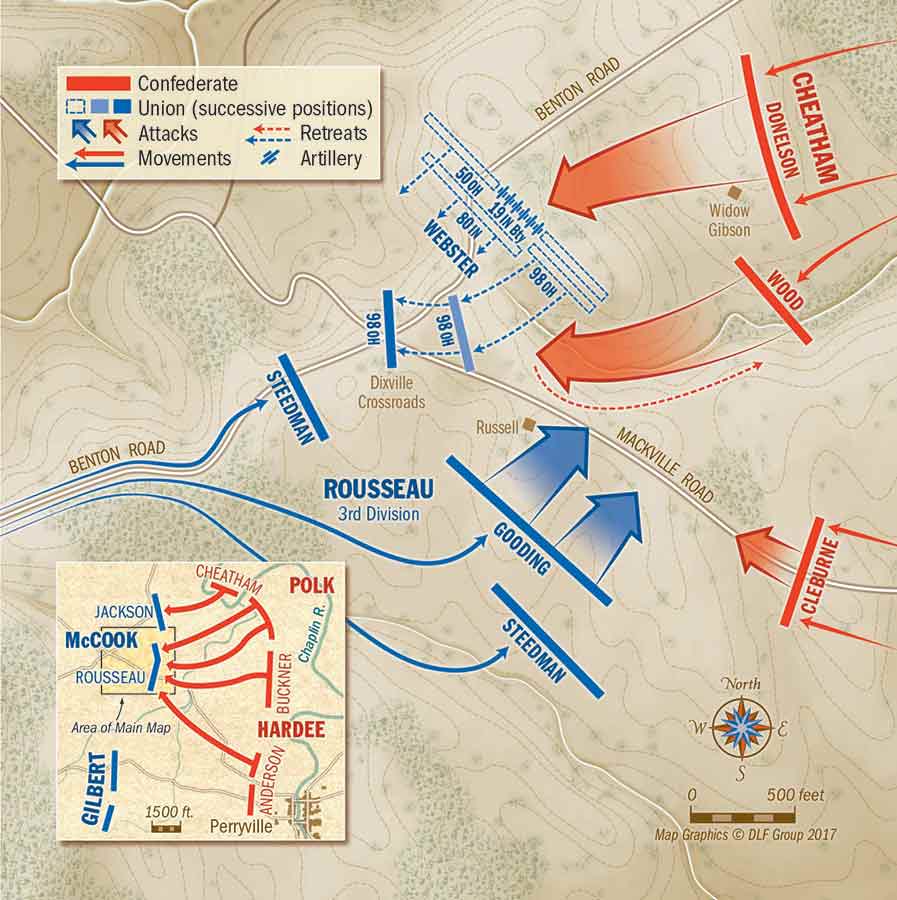

October 1 found the 98th on the march in search of Bragg’s army. The regiment was now part of the Army of the Ohio’s 34th Brigade, under the leadership of its former commander Colonel Webster. Seven days later at the small crossroads town of Perryville, Ky., the 98th would finally “see the elephant,” fighting for several crucial hours in an area later dubbed “The Slaughter Pen.” Private George Patton (related to the future U.S. Army legend in name only) was among those slightly wounded during a morning skirmish who missed the main battle later in the day. He was lucky. By sundown, the regiment incurred the brigade’s highest casualty toll. Of 822 men who reported for duty that morning, 230 were killed, wounded, or missing by the battle’s conclusion.

As they approached the battlefield, the men heard the roar of a ferocious artillery duel ahead. “A few of the boys began to get sick,” Corporal Wesley Smith Poulson later noted, “but most of them seemed to walk with more ease, as if there were springs in their legs.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]We could see plainly the columns of rebels approaching and their hateful flags flying[/quote]

Poulson thought of his Ohio home. “As we neared the field, we met many citizens, male and female, old and young, leaving for fear they would get hurt,” he wrote. Several “were crying at the thought [of] their houses destroyed, their stocks killed. The people of Ohio have had no such trials…but they have no surety that such a day will not come.”

The 98th assumed its initial position in the early afternoon, just below the crest of a ridge on the right flank of Captain Samuel J. Harris’ 19th Indiana Light Artillery. The gunners were exchanging rounds with Confederate cannons about a mile east. The soldiers lay on the ground as shells and cannonballs flew over their heads. A few somehow fell asleep, though most clung tightly to the earth.

“Shells were bursting around,” Poulson wrote, “and solid shot were making the soil fly up.” Added Sergeant Duncan C. Milner, a former divinity student, avowed abolitionist, and Hopedale Normal School graduate: “The earth we were lying on trembled from the concussion of the artillery….I saw a gunner struck by a cannon ball and knocked back 10 or 12 feet.”

Later that afternoon, Branum wrote, the regiment was poised “for the rebels to appear at the edge of the woods to charge our battery. The bullets soon came over our heads with a shrill, quick whiz, and we could hear them strike the fence and trees nearby.”

On the right, Confederate troops had taken a hill about half a mile distant and set up artillery that enfiladed the 98th’s position, “causing considerable loss,” Lieutenant Ellis E. Kennon wrote in his after-action report. Loud cheering then arose from the Confederates, and the Ohioans saw long lines of Alabama and Mississippi troops heading toward them. They “came at us from a wood on our right flank, eight lines deep,” Branum wrote. “[T]hey were brave fellows, and did not seem to care for their lives, and came on directly in the face of our fire.”

Meanwhile, the Confederates had overrun a battery north of the 98th’s position. Roughly an hour apart in that hotly contested area of the battlefield, the Federals suffered two significant setbacks when 10th Division commander Brig. Gen. James S. Jackson was killed and 33rd Brigade leader Brig. Gen. William R. Terrill—a Virginia native who had stayed loyal to the Union Army—was mortally wounded.

The Rebels were advancing on Webster’s left flank, using woods for cover. Then, on the 98th’s front, a “swarm of rebels [came] out of the woods about half a mile in front of us,” Poulson remembered. “When they got into open land and lines dressed, they started on double-quick shouting and hollering like wild men.”

As the Confederates closed to within 90 yards, Poorman wrote, Harris’ battery “ceased firing shell and round shot and hurled into the very bosom of the advancing host a storm of grape and canister, until the ground was literally covered with dead and mangled rebels.”

Nevertheless, the Confederates displayed impeccable discipline, reforming their lines, stepping over their dead and wounded, and continuing the charge. When orders finally came to withdraw Harris’ battery, the crews could salvage only two of the six guns, having lost so many horses. Poorman would note that several members of the 98th “stood by the remaining guns, and fired them several times” in the gunners’ absence.

The options looked bleak for the 98th. Branum feared they were on the verge of being overrun in front and on the right, recalling, “Our regiment was fast losing men….[O]ur position was untenable.”

A murderous hail of musketry greeted the Federals as they rose and formed ranks. Poulson made note of the fate of one Company F man who was hit almost immediately: “[T]he ball striking him in the face just below the left eye. Seeing his face so covered with blood and hearing the mournful noise he made seemed to strengthen my nerve.”

Poulson fired off several rounds before a bullet shattered his right leg. Collapsing near a tree stump, he played dead as the enemy swarmed his position. “I heard several balls strike the stump,” he remembered, “[and one Confederate] shot several times off the stump…the barrel extended over me, having bayonet fixed and gleaming.”

Leaving Poulson and other wounded comrades behind, the 98th worked its way down the ridge and then up a hill before reorganizing in a patch of woods near the tactically important Dixville Crossroads. “We could see plainly the columns of rebels approaching and their hateful flags flying,” Milner reported. “We were then moved a little higher up the hill, and renewed the fire with terrible earnestness. Here we lost a lot of our men either killed or wounded.”

Recalled Branum: “[O]n this wooded hill the battle raged furiously. The enemy on both sides were slowly working up, and the bullets grew so thick that one could imagine himself among a swarm of bees.”

One of those bullets found Colonel Webster, knocking him from his horse. “He told me he thought he was mortally wounded,” Milner wrote, “and prayed for God to have mercy on his soul: ‘Tell my dear wife and children they were last in my thoughts.’”

In a dispatch he sent to the Belmont Chronicle, the abolitionist Republican Poorman spoke fondly of Webster, the ardent Democrat. “[He] could be seen during the whole afternoon in the thickest of the fight…encouraging his men by his presence and advice—making his new recruits do the work of veterans. His death has cast a gloom over the 98th, by whom he was highly esteemed, and over his brigade that had learned to love him…an irreparable loss.”

Still, the regiment Webster originally commanded had delivered more than it received. Poulson estimated that he saw three dead Rebels for every Yankee cut down, and Poorman later wrote: “[The 98th] nobly stood up for an hour and a half under the fire of several regiments of the enemy, after every other [Union] regiment had fallen back on the right and left of it, and until the ammunition was completely exhausted.”

The 98th was relieved near the Dixville Crossroads, where a final Confederate assault soon stalled. As a full moon rose, some Rebel soldiers began robbing Union corpses, directly under the gaze of the exhausted Federals. The men of the 98th slept that night with their rifles clenched in their hands, expecting a renewed assault by the Confederates the next day. Instead Bragg withdrew.

The ferocity and toll of the battle was even more apparent by morning’s light. “The boys gave shot for shot and many a dead rebel on the field in front of us, bore testimony that they did not shoot in vain,” recalled Captain James M. Shane. Added Branum: “I saw almost 300 of our dead, lying thick in some places, shot in every imaginable way.”

Union and Confederate casualties during the battle totaled roughly 7,600. Survivors, such as Branum, reflected on how close they had come to joining the dead. “I got a bullet hole through my haversack, and almost everyone had holes through his clothes,” he wrote. Countless others had lost their hats, shot off their heads.

J.J. Polk, a local resident, walked the battlefield the next day. “All around lay dead bodies of soldiers both Union and Confederate,” he would write. “I counted 410 dead men on a small part of ground…[and] saw dead rebels piled up in pens like hogs. My heart grew sick.”

Perryville was a tactical victory for the Confederates, but strategically it signaled the beginning of the end. Remembered by some as the South’s High Water Mark in the West, it ensured that Kentucky and its vast resources would not join the Confederacy. Coming just three weeks after Antietam had ended Robert E. Lee’s first Northern invasion, Perryville was another battlefield “success” upon which Lincoln felt he could enact his Emancipation Proclamation and stave off foreign intervention on behalf of the South.

In January 1863, the 98th proceeded to Franklin, Tenn., where the officers bivouacked at the local courthouse. In a letter home, Branum revealed how much his once-snobbish attitude had changed. “A better class of men for their vocations could not be found,” he wrote. “All are endeared to each other from…the pleasures and hardships of our campaigning.”

Poorman returned to Ohio in June to help with Republican campaigning, and Shane—descendant of a War of 1812 hero—took his place. By August the 98th was itching to fight again. The men “are beginning to tire of inaction,” Branum wrote. “If there is any lying still to be done we will do it at home after the war.”

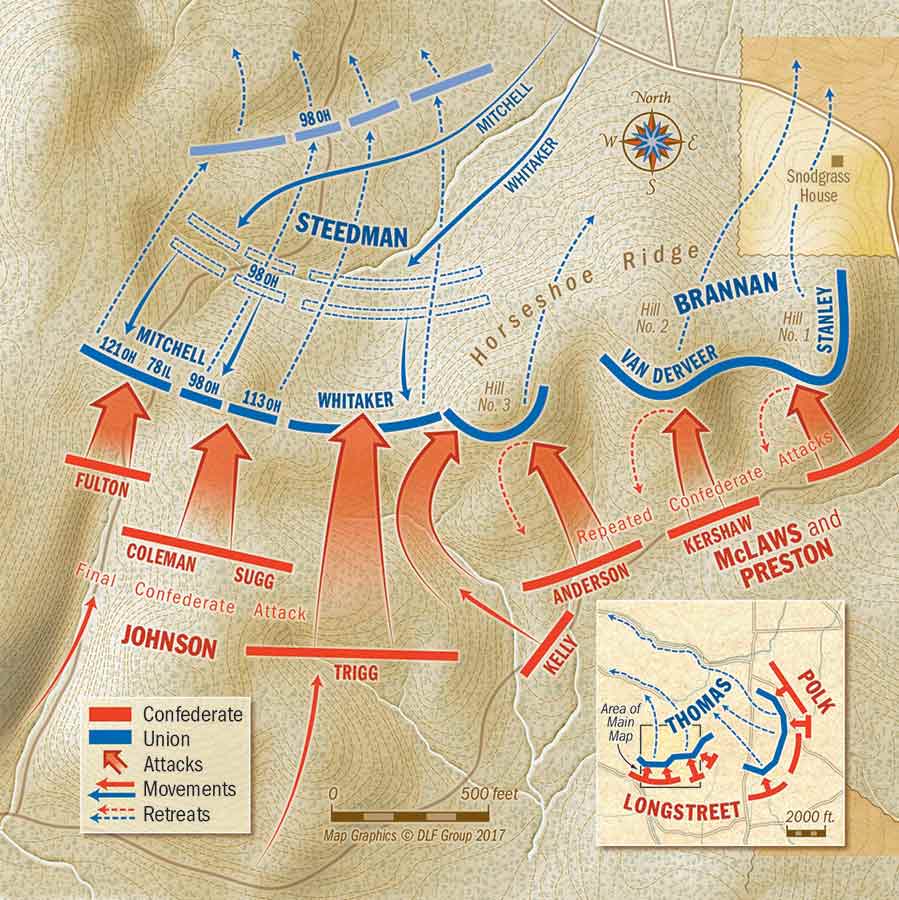

In mid-September the 98th got its wish, but paid dearly for it at the Battle of Chickamauga. Although Branum was confined to a hospital bed with a fever during the fighting, he “was compelled to listen to the roar of the battle and witness the sad scenes in the rear….[regimental surgeon] Dr. [Henry] West is up to his elbows in blood.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]‘He was my oldest school friend, and he was shot through the body’ – John Branum[/quote]

The young Patton, who had missed the Perryville fighting, was in the thick of the action. “Our little mess of four lost two of our number,” he wrote. His friend John Pollock had an arm amputated. “Went to the field hospital to see Pollock,” Patton wrote. “Found him in good spirits.” Pollock died a month later, however.

Patton’s other messmate, Johnson Hammond, survived his wounds, but was left “a cripple for life.” Another friend was shot in the head and died instantly.

At Chickamauga the 98th had only 196 men on the field, yet lost 50 killed and wounded, and 12 captured. One of those captured, Private Huston Winters, later died at the Confederates’ notorious Andersonville prison camp.

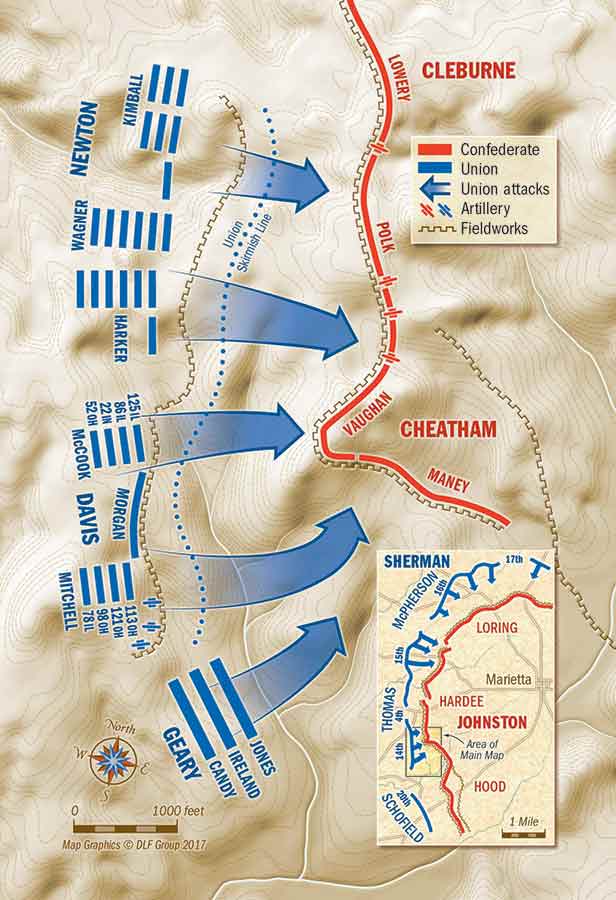

By the end of November the regiment had joined Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s armies at Chattanooga and had played supporting roles at Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain, losing only half a dozen men despite several brutal encounters. During the Atlanta Campaign—fought May to September 1864—the 98th saw action at Buzzard Roost Gap, Resaca, Rome, Dallas, Vining’s Station, Kennesaw Mountain, Peach Tree Creek, and Jonesboro. “This was a continuously fighting, skirmishing and marching affair,” Patton recalled. “I think there were only three out of the more than 100 days but that the balls were passing over us and in no case did we dare to lie down at night without having barricade or rifle pits to which we might fall into.”

Sherman continued trying to outflank his opponent, General Joseph E. Johnston, as he pushed toward Atlanta, but on June 27 mistakenly estimated that the Confederate army was stretched too thin and therefore vulnerable. At Kennesaw Mountain, he erred in launching a full-frontal assault. The 98th lost its latest commander, Lt. Col. James M. Shane, during that attack.

“Our beloved Col. Shane is no more, and 25 or 30 of our boys are killed or wounded,” Branum wrote. “As the charge started ascending a wooded hill, a torrent of bullets [began] streaming through our ranks….[O]ur men fell as fast as one could count.” Eventually, the assault stalled and the 98th dug in, just 50 yards from the enemy. After dark, Branum crawled forward to check the wounded. “The first one I came to was Harvey [sic] McKirahan,” he lamented. “He was my oldest Hopedale school friend, and he was shot through the body.”

Branum managed to get his friend to the rear, where he died, and then attended to Shane’s body. “His last words were, ‘My poor wife,’” Branum wrote. “I cannot express the grief that we all feel. What his poor wife will feel I fear to contemplate. Never were two more closely united in feeling and affection.” Lieutenant Colonel John S. Pearce assumed command.

Kennesaw Mountain was a Confederate victory, but Johnston abandoned the position five days later—a decision that helped prompt Confederate President Jefferson Davis to sack him and name the more assertive (though reckless) John Bell Hood as commander. Living up to the billing, Hood would lead more aggressively, but also suffered several devastating losses at Peach Tree Creek [see Reviews, page 60], and in two sharp encounters near Atlanta.

By the Numbers: 98th Ohio Volunteer Infantry

Original Strength (August 1862) 1,018

Original Recruits Mustered Out (June 1, 1865) 318

Killed/Mortally Wounded 120

Died While incarcerated 10

Died By Sickness/Disease 123

Died by accident 4

Discharged by WoundS/Disability 230

Oct. 8, 1862 Perryville (Ky.)

36 killed

194 w/M/C*

Sept. 19-20, 1863 Chickamauga (Ga.)

9 killed

54 W/M/C

Nov. 26, 1863 Graysville (Ga.)

5 killed

1 W/M/C

May 8, 1864 Buzzard Roost Gap (Ga.)

0 killed

1 W/M/C

May 13-16, 1864 Gesaca (Ga.)

1 killed

2 W/M/C

May 15, 1864 Rome (Ga.)

1 killed

0 W/M/C

May 27 — June 4, 1864

Dallas (Ga.) 3 killed

0 W/M/C

June 27, 1864

Kennesaw Mountain (Ga.)

8 killed

39 W/M/C

July 2-5, 1864 Vining’s Station (Ga.)

1 killed

2 W/M/C

July 19-20, 1864 Peach Tree Creek (Ga.)

1 killed

2 W/M/C

July 28 — Sept. 2, 1864 Siege of Atlanta (Ga.)

3 killed

3 W/M/C

Aug. 31 —Sept. 1, 1864 Jonesboro (Ga.)

12 killed

29 W/M/C

Nov. 15 — Dec. 21, 1864 March to the Sea (Ga.)

1 killed

0 W/M/C

March 19-21, 1865 Bentonville (N.C.)

10 killed

22 W/M/C

The end came on September 1 at the railroad depot of Jonesboro, just south of Atlanta. There the 98th Ohio joined another charge against a fortified position. “It was a terrible place to charge, being up hill,” Branum wrote. “[But] the troops rushed impetuously forward with cheers and flags waving…and we took the rebel works. They threw down their guns and surrendered at once.”

Although more than a thousand Confederate prisoners were taken, it was a bitter victory for the 98th, with 41 killed and wounded. The next day Hood abandoned Atlanta.

On October 8—two years to the date of the Battle of Perryville—rumors were circulating that Sherman was planning a “great raid.” Conceding that more fighting lay ahead, Branum wrote: “I dare not think of home. Of our quiet rooms, pictures, and books; the dinner table; of mother.”

Sherman’s epic March to the Sea, beginning November 15, would be a challenging but momentous experience for the Ohioans. By early December the 98th found itself near Savannah. The march had given Branum an opportunity to see the face of slavery up-close: “So many ragged and half-starved Negroes,” he wrote. “Each plantation has its little village of huts, which were bare of the necessities of life. Indeed, it seemed as though they raised the Negroes just like animals.”

Hundreds of former slaves began trailing the army. “Many families of Negro women and children followed us, from grandmothers down to babies…and had nothing to eat but what was thrown away or given them by the troops,” Branum wrote. “The poor slaves were willing to endure anything in preference to slavery.”

On December 9, though, Sherman’s rear guard forces, under Maj. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis’ command, set up pickets and stopped the black refugees from crossing swollen Ebenezer Creek, 20 miles from Savannah, casting them astray. Branum called it “a pitiful sight” but did allow that “it could not be helped, cruel as it seemed.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The poor slaves were willing to endure anything in preference to slavery[/quote]

Just before Christmas, Savannah surrendered without a fight. On New Year’s Eve, fireworks lit up the city. Wrote Branum: “Our country has passed through many dangers and struggles and is fast nearing the happy period of peace.”

In early February 1865, the 98th crossed into South Carolina. “About 50 Negroes came to our brigade today, and we met hundreds going to Savannah,” Branum wrote, now so accustomed to seeing “desperate, fleeing Negroes” pleading for sanctuary. “They will suffer great hardships, but are anxious for their freedom.”

As the 98th marched on, the men came across fine homes in ashes, blackened chimneys, and torched fences and crops. Farm animals not confiscated lay dead in the fields. “Lord, how wicked are we,” Branum wrote, noting also the familiar sight of white women and “their pretty little children” left helpless. “Will we ever have to atone?”

By late February the Ohioans knew the war was all but over. “We have conquered South Carolina [and] we can burn and destroy everything we please,” Branum wrote. “But where is our humanity? The motto of our Corps, on the acorn badge we wear, is ‘bravery and humanity.’ I would like to see more humanity exhibited.”

On a Sunday he wrote his family, “The country here is hilly, and much like [Ohio]. I can imagine you all at home today. I would like to hear the old church bell…once more.” By mid-March Sherman’s men were nearing Goldsboro, N.C., a railroad junction where they hoped to refit and rest. A soldier could now allow his imagination to run wild. Perhaps the war would end before the army left to meet up with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s forces.

In Virginia, Grant had Petersburg and Richmond under siege, with the Confederates ready to crack after nine months of trench warfare. Their only remaining chance was for Robert E. Lee to slip away, head west, and rendezvous with Johnston. Lee pressed Johnston to hit Sherman hard and stall his armies. On March 19, Johnston dealt his last card, assaulting Sherman’s left flank at Bentonville, N.C.

“We heard the sound of cannon ahead,” Branum wrote that morning. “We well knew that an hour of trial was at hand.”

That would be the last entry in his diary. Captain John W. Carson sent a letter to Branum’s father shortly after the three-day Battle of Bentonville, a Union victory. “The lieutenant was killed at the beginning of the battle,” Carson wrote. “He was about three paces from me when he was struck, and though deadly as the shot was, he did not fall instantly. He turned to me and said, ‘I’m killed, Captain,’ then made one step towards me and fell into my arms, saying ‘Take care of my things and send them to Mother.’ I laid him down slowly to the ground.”

Carson and Branum had both been at Hopedale, and had volunteered together. “Being old schoolmates and friends,” he added, “I loved him like a brother.”

It was the 98th’s final battle. Within weeks, both Lee and Johnston had surrendered. Though lacking Branum and so many of its original recruits, the regiment got a final day in the sun marching in the Grand Review in Washington, D.C., on May 24. Eight days later, the men mustered out, and headed home.

A regular contributor to America’s Civil War, Thomas M. Grace, Ph.D., teaches history at Erie Community College in Buffalo, N.Y.

Ohio native Allen F. Richardson, an award-winning journalist and author with a longtime passion for the Civil War, has covered living history in America, Europe, and the Middle East for the past 30 years.

Glory Days

As the years passed and the men of the 98th Ohio approached their 60s, they did what veterans across the country were doing—they started holding reunions. In 1897, the 35th anniversary of Perryville, they made one final, grand gesture and dedicated a monument to their first leader, Colonel George Penny Webster.

“The Gallant Survivors of the 98th Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry…Assemble in this City Again,” a headline proclaimed in the Steubenville Daily Herald. “There are only a few score present. The others have crossed the river of death, where all is peace forever more. The remains of many lie in unknown graves on Southern battlefields, others have been cut down by infirmities of age and sleep peacefully in neighboring cemeteries.”

Colonel John S. Pearce served as master of ceremonies, and Duncan C. Milner, now a Presbyterian bishop, as chaplain—delivering “an eloquent and touching invocation.” Honorary guests included surviving members of the Branum, Shane, and Webster families.

At Willow Mound, the Webster family plot, a 12-foot granite monument—patterned on the regiment’s marker at Chickamauga, and paid for by veterans of the 98th—was unveiled. “It is sweet and glorious to die for one’s country” was carved on the base.

“He was a man of splendid appearance: large, erect, dignified and soldierly, attracting attention wherever he went,” the head of the local bar association offered in a dedication speech. “At the same time, he was gentle and kind-hearted…and courteous to everyone. His manners were of the most polished character…”

Fortunately Webster’s story does not end there. Like many early American heroes, he came from an illustrious pioneer family, married a Mayflower descendant, and spawned several distinguished descendants.

One of them is his great-grandson, William H. Webster, 93, the former federal judge and director of both the FBI and CIA, who has chaired the Homeland Security Advisory Committee for the past 10 years. Webster also served as a naval officer in World War II and Korea.

“We think of him as an important member of our family,” Webster told us recently. “I have an original photograph of him in uniform that hangs in my house. It was his sense of duty and honor that impressed me the most…his example was in my mind when I made important decisions about my own career. He was always an inspiration. He set the path for me.”

In 2012, Webster paid tribute to his ancestor at Perryville itself, on the battle’s 150th anniversary. One ceremonial reenactment that day depicted the Confederate assault on Captain Samuel J. Harris’ battery, the 19th Indiana Light Artillery, and Colonel Webster’s 34th Brigade.

Among William H. Webster’s prize possessions are his great-grandfather’s gold watch—which he likely had carried during the battle—his commission papers, and letters written home to his wife. The colonel left behind five children, and a thriving law practice.

“His wife would plead with him to resign and come home, and he would tell her how much he yearned to do so,” Webster added. In one letter, apparently written just before Perryville, the colonel lamented that the war “has gone longer than any of us expected, but I can not leave my men. It is a matter of duty, and responsibility to them. I must stay.” –T.M.G. & A.F.R.