MANY YOUNG GIS in Italy from 1943 to 1945 were making their first trips overseas, and the vivid traces of ancient culture they encountered fascinated them. Troops landing at Salerno in September 1943 gazed at the awesome Greek temples at Paestum. A month later Naples fell to the Allies. That battered gem quickly became a magnet for tourists in olive drab, along with the Roman city of Pompeii. That city was destroyed in 79 AD by Vesuvius—mainland Europe’s only active volcano—and subsequently excavated.

The volcano itself, just east of Naples, proved an irresistible draw. The Red Cross organized jaunts up the smoking slope via funicular railroad. At the base, British and American troops gaped at “droolings of lava issuing from fissures,” as one American recalled. GIs drank “volcano-made coffee”; an urn of java lowered into the lava crust emerged piping hot. Volcanically toasted bread was popular. Souvenir hawkers did a brisk trade in ashtrays made from coins pressed into blobs of molten lava. GIs suspected—correctly—that not long ago the same vendors had been selling versions bearing Nazi insignia.

Vesuvius had erupted periodically for centuries and intermittently emitted reminders of its power. Small disturbances had been occurring more recently, but locals swore that when Vesuvio, as they called it, was noisy, all was well; the time to worry was when the mountain got quiet. Until March 1944 the volcano had hardly figured in the war, except as a geographic obstacle between Salerno and Naples. Once the Allies moved beyond Naples, the region around Vesuvius became a quiet rear area where pilots occasionally reported bumpy air caused by thermals rising from the crater. At night a dull red creep of lava mocked Allied blackout procedures by marking the route to Naples harbor—10 miles due west—for German aviators.

Many Allied units set up housekeeping in the vicinity. Just east of the restive mountain, the 340th Bombardment Group was based at Pompeii airfield, a new strip and a big improvement over the outfit’s previous field at muddy and overcrowded Foggia. Headquarters staff took over a villa three miles from the flight line; lower ranks made do with requisitioned houses or tents. Group headquarters and each of the four attached squadrons’ intelligence sections captured the experience in detailed histories and war diaries. “We found ourselves based on a fine field cleared among orchards and vineyards,” one such diary recorded. “Vesuvius reared up into a soft blue sky a few miles away, smoking and steaming quietly. ‘Used to erupt’—someone had said. We all knew that was away back in dead history somewhere.”

KNOWN AS “THE AVENGERS,” the 340th—part of the Twelfth Air Force—flew the North American B-25 Mitchell medium bomber. The unit began its war in early spring of 1943 based at Medenine, in southeast Tunisia, bombing Afrika Korps chief Erwin Rommel’s supply lines. By year’s end the crews were at Foggia, assisting the Allied slog up the Italian boot. With a Distinguished Unit Citation in hand the 340th’s fliers thought they were hot stuff—though even the hottest hands had to admit the unit’s bombing accuracy and formation discipline had slackened lately. Spells of bad weather, inactivity, and boredom had dulled the group’s edge. Change was in order.

New Year’s 1944 brought relocation to Pompeii field and a new broom. On January 8 Lieutenant Colonel Charles D. Jones assumed command, immediately laying on rigorous practice missions and scrutinizing the results. Another skipper making the same demands might have raised hackles, but Jones’s affable professionalism and high standards quickly won converts. Soon Jones was “whipping the group into its old-time condition of morale and efficiency,” a war diarist noted. By mid-January, the group was striking enemy transport choke points in support of the Anzio landings. By all measures, performance dramatically improved.

On March 10, 1944, over the Littorio marshalling yards north of Rome, flak took down the bomber in which Jones was flying. Observers saw five of seven crew members parachute safely before the blazing B-25 augered in. German radio soon announced that the “popular and esteemed” Jones was a POW.

A week later the unquiet Vesuvius became even more so. Daily, the crater sent an enormous pillar of steam and smoke miles into the heavens; by night, huge lava spouts arced skyward. A new lava flow a mile long, a quarter mile wide, and eight feet deep began slithering toward Naples.

Even so, Pompeii field seemed safe. “From our side we could see only the usual bubbling red cone and silhouette, no lava flowing,” one war diarist wrote. The 340th’s new commanding officer, Colonel Willis F. Chapman, decided to stay put. He wanted to keep attacking the enemy, and avoid tempting Luftwaffe night raiders by crowding nearby fields. He also had faith in locals’ assurances. Flights of B-25s kept hitting targets through March 20, as Vesuvius, in the words of a nervous airman, continued to “grunt like a giant pig.”

Events of March 21 called Chapman’s judgment into question. “Vesuvius going stronger than ever,” a squadron member dutifully recorded. “At suppertime blasts were getting to be one continual rumble and just after supper it began to seem that the whole top of the mountain was going to come off…the lava started to come down our side, dropping in big hot flows like metal in a foundry. The towns of San Sebastiano and Massa di Somma were being overrun by the lava today, a stream 50 feet high, slowly engulfing everything in its path. Trees, a hundred feet away, suddenly swell and burst from the expanding sap and are immediately consumed with fire.” GIs hauled terrified civilians to safety, the impromptu convoys blocked by camera-toting soldiers heading to the lava flow the locals were trying to escape.

Near midnight the mountain seemed to calm itself, but at 2 a.m. the crater began spewing pea-size pellets. By dawn on the 22nd, a “black snow storm” of ash was falling “and the missiles had grown to walnut size with occasional baseballs,” wrote Captain Everett Thomas of the 488th Bombardment Squadron. Lightning, a frequent accompaniment to volcanic eruptions, added to the spectacle. Bolts at the summit seemed to summon larger spouts of lava. Still, group headquarters, in that sumptuous villa some three miles from the flight line, did not grasp the situation. Command staff instructed ground crews to “keep the wings shoveled off and the planes protected as well as possible,” Thomas wrote.

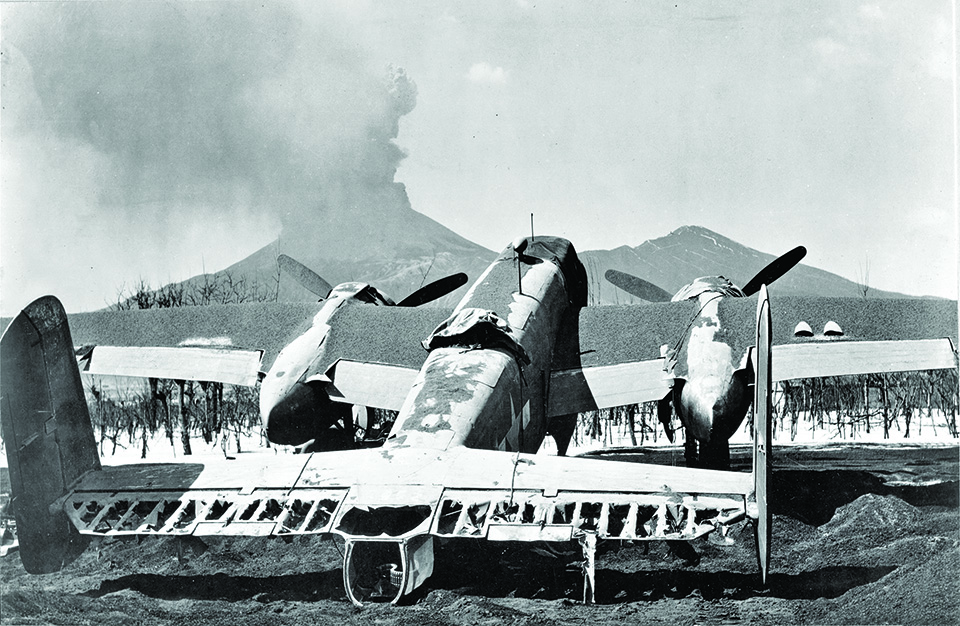

Now the volcano was throwing superheated pyroclasts the size of footballs that shattered on impact to reveal glowing white-hot cores. “The phenomenon had passed a bit beyond the purely interesting stage,” a droll ground crewman reported. Chunks of hot rock smashed plane turrets and cockpits, ripping through fabric control surfaces. Despite frantic sweeping, heavy ash accumulated on wings and fuselages. Finally, after several hours of confusing orders and counter-orders, the group’s personnel evacuated the shattered base, leaving behind not only ruined aircraft but most of their equipment and personal possessions. In trucks and jeeps, the bedraggled convoy crept along roads covered by a foot of drifting volcanic ash.

By nightfall the worst was over. Civil and military authorities tallied 28 dead, mostly locals. The personnel of the 340th got off very lightly; the only injuries were a broken nose and a broken arm. GI medics treated evacuated civilians. The sight of San Sebastiano horrified one British soldier. “Where it had stood was nothing but a big slag heap of lava, and a memory,” he wrote in a letter to his parents. “Bombs make a terrific row and leave ruins. Lava makes no sound and leaves—nothing.” The men of the 340th returned on March 25 to Pompeii field, hoping to find only scorched paint and fabric and destroyed Plexiglas. But heaped tons of volcanic ash had twisted wings and tail surfaces, reducing many bombers to scrap.

German radio propagandist Axis Sally ballyhooed the disaster, claiming Germany had nature on its side. “We got the colonel,” she crowed, referring to the captive Jones. “Vesuvius got the rest.” German radio claimed the group had been wiped out to the last man and ship. “She was nearer right than she knew on ships at least,” one squadron historian lamented.

ASH AND SOOT SIFTED from the sky for weeks, but the Avengers recovered swiftly. Only four days after the evacuation the group was flying again from a field near Paestum with six borrowed B-25s per squadron. Replacements returned the unit to full strength, using the latest model B-25, by mid-April. All 88 Mitchells at Pompeii—$25 million worth—seemed to be shot to hell, but maintenance crews cannibalized hulks until, by the end of April, they had 14 planes in working order. From Paestum the unit followed the Allied advance, relocating in late April 1944 to Alesan airfield on the east coast of Corsica, so checkered with American bases that crews nicknamed the island “USS Corsica.”

As the 340th resumed its attacks on German infrastructure, the press of combat pushed thoughts of Vesuvius to the side. Jones’s admonition to watch for enemy sorties became sidelined as well. Even unit war diaries noted that complacency was again setting in. Aside from the occasional nuisance raider or photo-recon snooper, the Luftwaffe had never brought a serious attack to bear on the 340th at any of its bases. Protection by Allied night fighters patrolling out of other Corsican fields added to the sense of invulnerability.

On May 12, 1944, the airmen gathered for movie night. The popular 1943 comedy Holy Matrimony, starring Gracie Fields and Monty Woolley, had men rolling in the aisles—even after they saw tracer fire to the north, which they assumed was from nuisance raiders. “Like children,” a squadron diarist recorded, everyone enjoyed the sight of streams of incendiary rounds.

What 340th personnel were seeing was a heavy Luftwaffe attack on Poretta airfield, 15 miles north and home to the fighters that guarded Corsica’s Allied bomber bases. The Germans, knowing an enemy offensive was in the works, had coordinated efforts to disrupt Allied air cover for that attack and take pressure off fellow defenders. The Junkers Ju 88 bombers that hit Poretta returned to Ghedi in northern Italy to rearm and refuel, and set out again—this time for Alesan.

At 3:30 a.m. on May 13, a German pathfinder laid flares among the base’s dispersed B-25s, many of them brimful of fuel and loaded with ordnance for the morning sortie. “The flares make the field appear as though there is a night baseball game being played back home,” a 489th Bombardment Squadron member wrote. “I can hear planes overhead but cannot see them.” Enemy fragmentation and light demolition bombs shredded the parked planes. “Planes continue to burn,” the writer continued. “It is a holocaust but an awe-inspiring one.”

The Luftwaffe killed nearly two dozen men and injured more than 75. Ground crews—some in slit trenches, others caught in the open—took especially heavy casualties. Several of the dead were new arrivals, their gear barely unpacked. Tightlipped airmen trudged to the medical tent to donate blood for the wounded. Of the 65 B-25s the Germans hit, 30 were total losses. Some Americans noted that Vesuvius had done worse damage, but most agreed with a squadron diarist’s sentiment: “Vesuvius was bad but man wreaks much greater destruction than nature.” The string of funerals hit the 340th hard. Men lamented their carelessness in days past, when wearing helmets and digging slit trenches “was considered almost cowardly,” a diarist wrote. “Have we learned a bitter lesson?” All four squadrons resolved that if the Luftwaffe returned, the Germans would find everyone at last dug in.

The 340th rebounded, mounting a mission the next day. Colonel Chapman stayed in command, and welcomed the newly freed Jones at war’s end. In September 1944 the group received another Distinguished Unit Citation—and in time became unexpectedly immortal. Eight days after the Alesan raid, a replacement bombardier arrived. Lieutenant Joseph Heller, 21, soaked up chatter about the attack, flew 60 combat missions, and throughout took heed of personalities and events on Corsica. In 1953 Heller began transmuting his war into fiction; in 1961, Simon & Schuster published his novel Catch-22, which became a bestseller and remains in print.

But that is another story.

Originally published in the September/October 2015 issue of World War II magazine. Photos: National Archives