It took a century and a half and the tireless work on dissenting Friends to create the first White-dominated antislavery movement

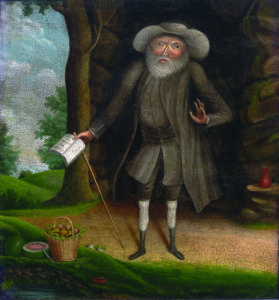

That Benjamin Lay, a hunch-backed dwarf with an oversized head and spindly legs, stood out in his opposition to enslavement would be an understatement. Lay, a Quaker, was among the most strident American abolitionists of the early 18th century. He pricked the consciences of coreligionists fearful of bucking Quaker doctrine with theatrics that traded on his startling appearance. Born in Colchester, England, and now a Pennsylvanian, Lay agitated against Quakers’ role in slavery as owners, traders, and participants in businesses reliant on bondage.

Lay’s protests, carefully planned and uproarious, left an indelible impression. One wintry Sunday morning in 1733-34, Lay—coatless, right foot and leg bare in the snow to remind onlookers of how cruelly slaveowners treated their human chattel—posed outside a Quaker meetinghouse in Philadelphia as a Meeting for Worship ended. Congregants admonished him not to make himself sick.

“Ah, you pretend compassion for me but you do not feel for the poor slaves in your fields, who go all winter half clad,” he replied.

On Friday, September 19, 1738, Lay attended a large Quaker assembly, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, in Burlington, New Jersey. Wearing a military greatcoat over a soldierly uniform, complete with sword, he carried a book. In a hollow between the covers, he had fitted an animal bladder brimful of pokeberry juice, which runs a rich red. When his turn to speak came he hefted the oversize volume, railing at Friends whose hands Lay decried as soiled by bondage. “Thus shall God shed the blood of those persons who enslave their fellow creatures!” the strange little man shouted, throwing off his coat, pulling his blade, and stabbing the book. Gouts of red splattered him and all nearby, shocking everyone at hand. Ejected from the hall, Lay went along without protest. Soon after, disowned—excommunicated—by his home Monthly Meeting in Abington, Pennsylvania, Lay dropped from sight and the Quaker community, living for 20 years as a hermit in a cave outside Abington.

Before Lay’s performative but compelling protests, other Quakers took their fellows to task for participating in the American colonies’ slave-driven economy. William Southeby, John Farmer, and Ralph Sandiford challenged mainstream Quaker values, decrying enslavement and laying the foundation for what became the abolitionist movement and a nation’s grudging redirection toward emancipation.

George Fox was born in Leicestershire, England, in 1624. At age 21, after years of spiritual searching, Fox reported hearing God say, “There is one, even Christ Jesus, what can speak to thy condition.” In 1652, after a vision in which Christ revealed to him “a great people” to be gathered, Fox founded the Religious Society of Friends—dubbed “Quakers” by skeptics for their tendency to “tremble at the Word of the Lord.” Fox was a charismatic leader; by 1660, he had 50,000 followers in England divided geographically into “meetings” each named for a city in that region.

Quakerism opposed the ritualistic Church of England. The Friends had no set ceremony, no minister. They believed “there is God in every man” and posited that an “inward Light” led to personal salvation without clerical intermediaries; in God’s sight, all were equal, they said. Citing the Golden Rule, Quakers refused to serve in the military or take judicial oaths. Despite the deliberate absence of a clergy, someone had to organize matters, leading to the creation of committees, or “overseers,” of particular functions, including the publishing of tracts by individual Friends.

Quakers’ radical stances brought condemnation. English authorities beat, whipped, and imprisoned as many as 15,000 Friends—Fox was jailed eight times—until the 1689 Toleration Act granted the sect freedom to practice. By that time many Quakers had fled England for relative safety in North American and Caribbean colonies, particularly the West Indies, where Quaker missionaries first arrived in 1655. By 1700, approximately 10,000 Friends had settled in Jamaica, and substantial numbers in Barbados.

Barbados functioned as a strategic hub for England and its North American colonies, exporting sugar, rum, tobacco, cotton, indigo—and enslaved Africans. Slaving drove the Barbadian economy. Wealthy Quakers—plantation owners, merchants, ship owners—were among the many entrepreneurs active in the business.

At home and abroad, English society assumed less commercially minded Friends to be anti-government. Quaker missionaries Mary Fisher and Anne Foster sailed from Barbados to Boston in 1656, encountering the wrath of the city’s Puritan leadership. After five weeks behind bars, the two were shipped back to Barbados. They got off light; during 1659-61, the gibbet at Boston Common saw four Friends hanged for merely entering the colony. Around this time, Quaker preachers also were reaching the southern American colonies.

From a small cadre of zealous missionaries, the 17th-century Quaker presence in North America grew rapidly as Friends flocked to new colonies and many other settlers converted. Quakerism persisted in Massachusetts and flourished in Rhode Island and the Chesapeake colonies. In the 1670s-80s Quakers founded the colonies of West Jersey and Pennsylvania. Beginning with communities in New England in 1661, the Quakers had by 1700 established six regional Yearly Meetings in the colonies, mirroring arrangements in England. In the colonies, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting was first among equals.

Not a few Quakers embraced the slavery already entrenched in the colonies, even though owning another person violated Quaker philosophy. Many Friends settling in North America were wealthy Barbadians, bringing along their slaves and indentured servants.

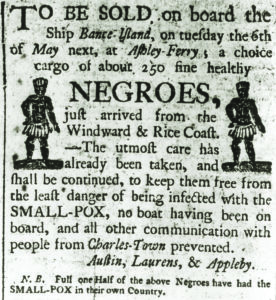

By the 1680s more than half the ships in Boston harbor were involved in the West Indian trade in sugar, rum, cotton—and slaves. Via Barbados, the ports of Newport, Bristol, and Providence, Rhode Island were leading centers of the slave trade. William Penn’s “Holy Experiment” of Pennsylvania was not immune. In 1690, less than ten years after founding the colony, Penn reported that ten slave ships had arrived from the West Indies in a year.

For all their palaver about the Golden Rule and equality, many Quakers, like others of their time, saw importing and owning Africans as acceptable. Those enriched by bondage scorned talk of equality, even by the sect’s founder. Fox himself spoke up on behalf of the enslaved, albeit blandly, in a 1657 epistle, To Friends Beyond Sea, that have Blacks and Indian Slaves. Friends, Fox said, should “have the mind of Christ, and to be merciful, as your heavenly Father is merciful” and preach the Gospel to “every creature.”

In 1671, accompanied by a dozen English and Irish colleagues, Fox spent five months in Barbados and Jamaica. He shuddered to see the condition of slaves, even those owned by Friends, on Barbados. Fox mildly admonished followers there to teach their slaves the Gospel and treat them kindly but stopped short of advocating emancipation.

Continuing to the North American colonies in early 1672—they landed at Patuxent on Chesapeake Bay—Fox and company, intent on organizing monthly and general meetings like those back home in England, crisscrossed the colonies north and south from Maryland for 13 months. No doubt Fox, while among slave-holding believers, communicated his concern for the well-being of their human property.

In 1676, Fox published Gospel Family-Order, Being a Short Discourse Concerning the Ordering of Families, Both of Whites, Blacks and Indians. This slightly more incisive pamphlet incorporated his 1671 sermons on Barbados. Friends were not to slight “the Ethiopian, the black man, neither man or woman upon the face of the earth, in that Christ died for all” and “to let them go free, after a considerable term of years,” he wrote.

In 1679, Fox again addressed slavery, but—as in all his writings—without flatly condemning the practice. In To Friends in America Concerning Their Negroes, and Indians, the founder admonished Quakers in America to convert persons they held in bondage, beginning his epistle, “All Friends, everywhere, that have Indians or blacks, you are to preach the gospel to them, and other servants, if you be true Christians.”

William Edmundson, an Irish-born minister who had traveled with Fox on the founder’s first trip to North America, took the step that Fox would not. On his return to the colonies in 1675-76, Edmundson attacked slave ownership outright: “And many of you count it unlawful to make slaves of the Indians,” Edmundson asked. “And if so, why the Negroes?” These and other goads began to turn Quakers away from benign neglect and toward activism.

On February 18, 1688, Friends living in Germantown, Pennsylvania, outside Philadelphia, staged the first formal anti-enslavement protest in the colonies. Two months later, also from Germantown, came a broadside against enslavement likely drafted by attorney Francis Daniel Pastorius, the Bavarian émigré who had founded Germantown. Signed by Pastorius and three others, including the clerk of their Meeting, the document began, “These are the reasons why we are against the traffick of men-body as followeth,” that enslavement violated the Golden Rule, that tolerating the practice would give Pennsylvania a bad name, and that keeping slaves meant a risk of a slave revolt. “Now consider well this thing, if it is good or bad?” the paper asked.

The Monthly Meeting at Dublin, Pennsylvania, ignored the Germantown declaration, finding enslavement “so weighty that we think it not expedient for us to meddle with it here.” The petition wound its way to the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, whose members forwarded the message to the London Yearly Meeting.

Both bodies declined to pursue the matter. Individual Quakers and local Meetings embraced the abolitionist cause, the first Christian denomination to do so. The Germantown protest exerted little direct impact, but its accompanying text inspired Quaker abolitionists into the 19th century.

In 1693, the Keithians, a splinter group founded by Quaker George Keith, published An Exhortation and Caution to Friends Concerning Buying or Keeping of Negroes. Largely ignored by mainstream Quakers, the Exhortation called enslaved persons captives of “war, violence, cruelty, and oppression; and theft and robbery of the highest order.” The Golden Rule applied to all regardless of “what generation, descent or Colour they are.” Enslaving Africans is a sin, the Keithians said. In 1696, prodded by multiple Friends, including prominent minister William Southeby, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting began to grapple with slavery’s moral implications.

Termed the “first native-born American to write against slavery,” Southeby, a Marylander who converted from Catholicism, was the leading anti-slavery Friend of his day.

Southeby’s essay, To Friends and All It May Concerne, interwove arguments by Fox and Edmundson, the Germantown Friends, and the Keithians. Southeby’s exhortation and salvoes by Robert Pyle and Welshman Cadwalader Morgan persuaded the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting to formulate the advice that “Friends be Careful not to Encourage the bringing in of any more Negroes.”

Southeby found that language mealy-mouthed and likely to be ignored. So vigorously did he issue jeremiads that Philadelphia Quaker leaders twice censured him, though they apparently did not disown him, perhaps because, to preserve unity, he seems to have cooled his ardor. He was a Friend in good standing when he died in 1722.

The Philadelphia Meeting was not at all alone in shillyshallying on slavery. Meetings throughout the colonies discouraged anti-slavery expression by members. However, John Hepburn’s local Meeting in New Jersey did not blink in 1715 when the former indentured servant published his incendiary American Defence of the Christian Golden Rule, Or An Essay to prove the Unlawfulness of making Slaves of Men, the longest and most logically written attack on slavery yet to be circulated in the American colonies. Summarizing the anti-enslavement debate, Hepburn articulated the theology behind his condemnation—mankind’s free will comes from God, and enslavement denies Africans their free will. Hepburn emerged from notoriety unscathed.

Visiting English minister John Farmer wasn’t as fortunate. Farmer brought an epistle, Relating [sic] Negroes, to the 1717 New England Yearly Meeting at Newport. His message incensed the Yearly Meeting’s leaders, wealthy slave-owning and -trading Quakers. They “advised” he not publish. Farmer published and was disowned. Unapologetic, he traveled to Philadelphia and read his epistle at every opportunity, incurring the enmity of the city’s obdurate Quaker elite. The Philadelphia Monthly Meeting upheld Farmer’s disownment, as did the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1720, one of Quaker history’s rare double disownments. After the Southeby and Farmer episodes, no Friend from any Philadelphia Meeting spoke out for almost a decade. Antislavery sentiment was slowly spreading among rural Friends, but when English emigrants Ralph Sandiford and Benjamin Lay arrived in Pennsylvania—Lay, disowned by his congregation in England for disrupting meetings, came from England by way of Barbados—the pro-slavery perspective remained in comfortable control of Quakerdom’s Philadelphia establishment.

Sandiford, a merchant from Liverpool who bristled at sympathetic fellow Quakers for not speaking what they clearly felt, began attacking enslavement soon after he landed. In 1729, after a warning not to proceed from the Overseers of the Press, Sandiford published A Brief Examination of the Practice of the Times, questioning the injustice “to rob a Man of His Liberty, which is more valuable than Life?”

The Philadelphia Monthly Meeting ostracized Sandiford. With slavery weighing on his mind such that “the sense of it [had burdened his] life night and day” a year later he issued The Mystery of Iniquity; in a Brief Examination of the Practice of the Times, by the foregoing and the present Dispensation. The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting disowned him. Sandiford retired to a farm outside Philadelphia. In his later years he and Benjamin Lay became friends. Sandiford died brokenhearted in 1733.

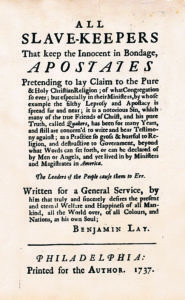

Lay regarded Sandiford as a martyr, and after his friend’s death intensified his outspokenness, penning All Slave Keepers, That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates. In it, Lay called keeping enslaved persons “a Practice so gross and hurtful to Religion, and destructive to Government, beyond what words can set forth.” Benjamin Franklin printed the book in 1738. Three weeks later Lay pulled off his pokeberry juice exploit and was disowned—the last Friend to be cast out for fighting slavery.

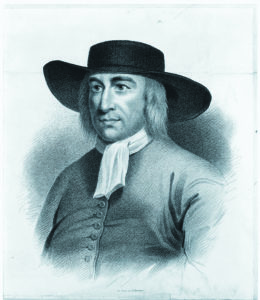

By staking out extreme positions, Lay, Farmer, and Sandiford had laid a firm line of resistance. Mainstream Quakers needed a figure less strident to get them into action. John Woolman, a merchant and tailor from Mount Holly, New Jersey, and a minister of the Burlington Monthly Meeting, became that leader—according to historian Thomas Drake, “the greatest Quaker of the eighteenth century and perhaps the most Christlike individual that Quakerism has ever produced.”

Woolman spent his youth unconcerned about enslavement. However, in 1742, when he was 22, his employer had Woolman draw up a bill of sale for an enslaved woman. The transaction deeply unsettled the young man. In 1746, he joined other missionaries preaching in the southern colonies, traveling as far south as North Carolina, seeing slavery up close for the first time. Slave-owning Friends reacted coolly when he counseled emancipation, but he persevered, visiting and revisiting, a gentle persuader who gradually changed a Society’s thinking.

Returning home to New Jersey, Woolman wrote Some Considerations on the Keeping of Negroes: Recommended to the Professors of Christianity of Every Denomination. “All men by nature,” Woolman argued, “are equally entitled to the equity of the Golden Rule, and under indispensable obligations to it.” However, he waited until 1753 and a change in makeup of the Philadelphia Overseers of the Press to present his tract for review. Approval and the pamphlet’s publication in 1754 marked a major shift in the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting’s attitude. That shift intensified in 1758 when the Yearly Meeting approved “without spoken dissent” a recommendation that Friends free those they held in bondage. Lay learned of the advice shortly before he died in 1759.

By 1760, 50,000 to 60,000 Quakers lived in seacoast colonies, about half in areas around Philadelphia and in Maryland. Other Christian sects now outnumbered Quakers in North America. The Friends downplayed proselytizing, instead turning inward and institutionalizing their doctrine with such strictures as prohibiting marriage outside the Meeting and threatening disownment for “errant” Friends, stances that cost them members.

Friends’ pacifism came to the fore during the French and Indian War, at the cost of political power. In 1756 Quaker legislators stormed out of the Pennsylvania Assembly to protest war taxes, relinquishing control of the government, abandoning provincial politics, and focusing on social issues. The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting’s endorsement of emancipation came at a propitious moment.

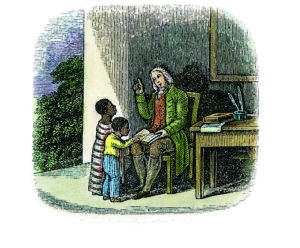

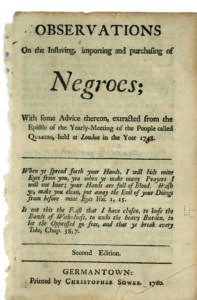

Woolman had an influential ally in Anthony Benezet. Though not nearly as dramatic as Lay, Benezet, an émigré from France via London, worked tirelessly within the Quaker system. A prolific writer, he penned many pamphlets and petitions, beginning with 1759’s Observations on the Enslaving, Importing, and Purchasing of Negroes. Benezet said if Friends believed God was in every man, bondage must be a sin. Teaching black children in his home at night, he promoted the novel idea that all people are capable of learning and thus are equal and deserving of freedom. Benezet and allies among the Friends made their arguments to government as well as to fellow believers.

The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting’s advice became a movement. Yearly Meetings from New England to North Carolina took steps toward banning enslavement within their Meetings, to find that many Friends preferred to keep their slaves and be disowned.

Even Quakers willing to free their slaves could not necessarily do so. Virginia and the Carolinas sharply restricted the freeing of slaves except with government approval and only for meritorious service. Slave-owning Friends wishing to manumit had to choose: be disowned or leave the state. Hundreds of Quakers relocated west in Ohio and Indiana, taking their human chattel and liberating them upon arrival in the “free” territory. Some Northern Virginia Friends immediately freed slaves, but most waited until 1782 when that state’s anti-manumission law was changed after heavy lobbying led by abolitionist planter Robert Pleasants. A friend of Benezet and Woolman, he also presided over the short-lived Virginia Abolitionist Society in 1790. Pleasants, a planter and abolitionist, persuaded Virginia legislators to legalize manumission by last wills and testaments or other writings validated in a county court by two witnesses. Upon the legislative revision, he freed his slaves and hired them as paid workers.

During the American Revolution, Quakers throughout the colonies struggled to remain neutral; many had property and goods forfeited and some were exiled, but Benezet, now an “old white-haired busybody of good works scurrying around with a petition in one hand and an article against slavery in the other,” never quit.

Neither did Warner Mifflin.

Mifflin, a charismatic abolitionist in the Benjamin Lay mold, was the physical opposite of his antecedent, standing just under seven feet tall. After Benezet died in 1784, Mifflin became the most widely known Quaker in America, serving as the bridge between the early abolitionists and the wave of activists arising in the 1830s.

A Delmarva Peninsula planter’s son, Mifflin owned slaves until a serious illness in his late 20s, during which he was “fully persuaded in my conscience that it is a sin of a deep dye to make slaves of my fellow creatures.”

The younger Mifflin freed his enslaved persons in 1774 and paid them reparations, one of the first slave owners to do so. He persuaded his father to do the same. After the Revolution, Mifflin became a prominent lobbyist, promoting abolition, a cause that began to attract non-Quakers. Southerners called him a “meddling fanatic,” while fellow abolitionists praised his efforts.

The North Carolina Yearly Meeting took an extraordinary step in 1808 to end-run that state’s pro-slavery laws—the Meeting itself became the agent of its members’ enslaved persons. Friends “gifted” their slaves to the Yearly Meeting, which treated them as “free.” Slave owners challenged the program in court, but Judge William Gaston ruled that under a 1706 state law the Quaker trustee system was constitutional. By 1814 the yearly meeting “owned” 350 slaves; by 1826, 729. The trusteeship was dissolved on January 1, 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation freed slaves in Union-occupied territory.