Nearly five decades after the war, Southern officer remembers the confrontation that led to Federal retreat

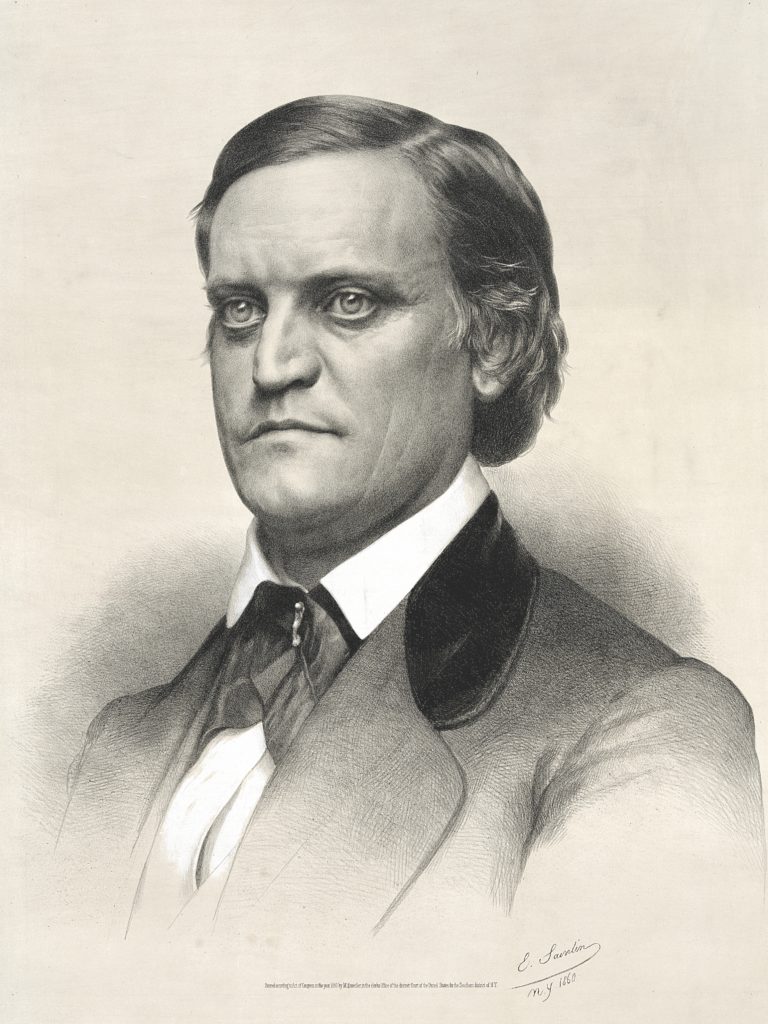

Benjamin S. Williams, adjutant of the 47th Georgia Infantry, penned this memoir for the October 29, 1911, issue of the Charleston, S.C., Sunday News. Williams moved to South Carolina after the war and died at 87.

At the close of day, September 19, 1863, [Maj. Gen. John C.] Breckinridge’s Division, of [Lt. Gen.] D.H. Hill’s Corps, weary, worn, and hungry, was on the edge of the battlefield of Chickamauga. Many of our wounded passed us in ambulances. [Lt. Gen. James] Longstreet’s Corps had been sent from Virginia to reinforce [Gen. Braxton] Bragg; many of the wounded were newly arrived soldiers of the Virginia army.

Bragg ordered Breckinridge to move to the right and farther front. We passed many dead Confederates and a few Federals. We rested under orders to sleep on our arms. We were up early Sunday. We were very hungry.

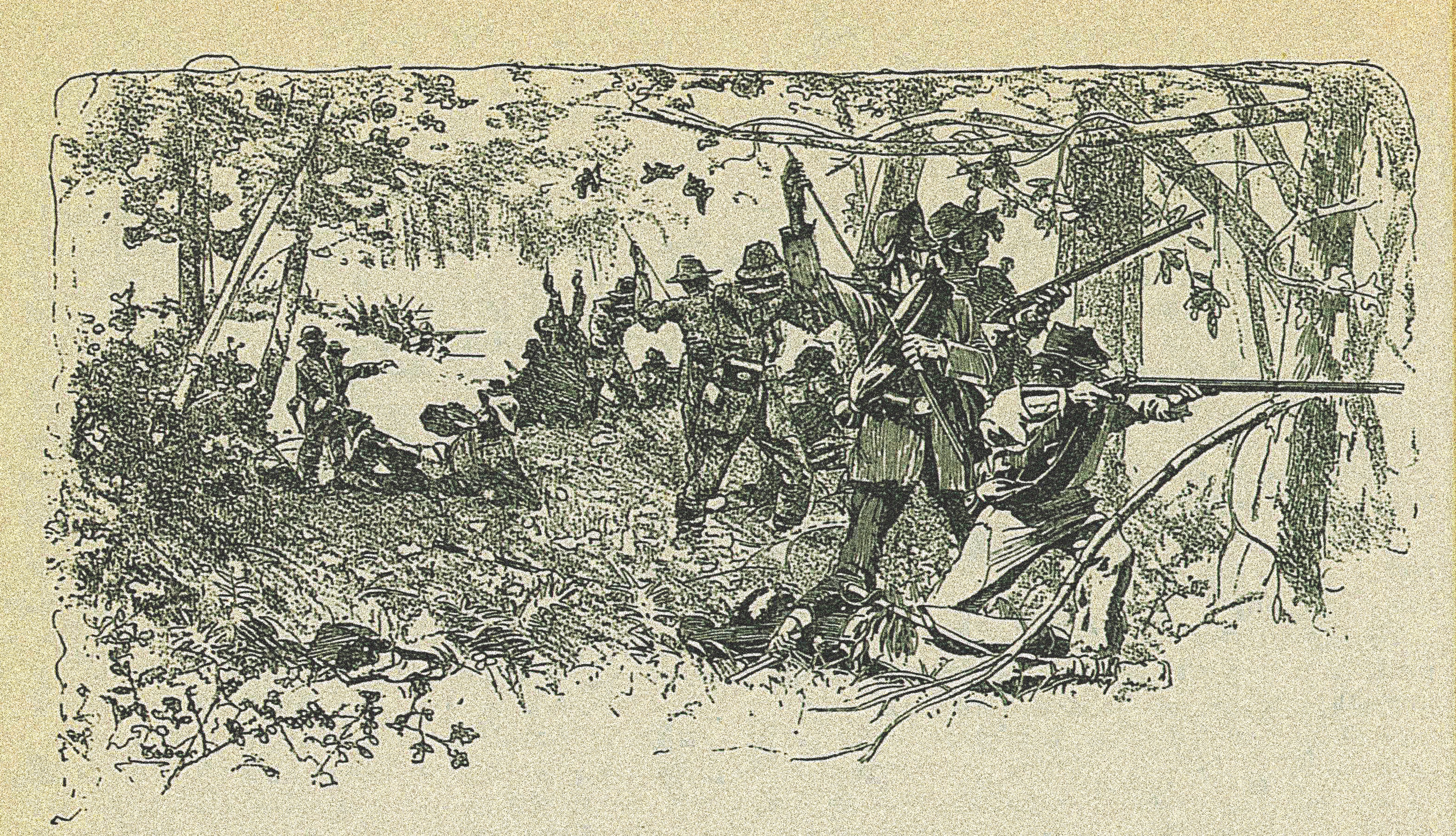

We were ordered to advance in line of battle 300-400 yards. We emerged from this wooded tract into open meadow-like ground where we encountered fire from a line of skirmishers in the wood beyond. They retired hastily before our advance and the Federal batteries in their rear opened fire with solid shot and shell, firing high, their shot crashing through the treetops above us. We were now in the wood through which the blue skirmishers retreated. Here we were halted while some of Longstreet’s brigades moved to our left that we might take position on the right and attack the Federal left wing. “Attention” rang out down our line and we knew that our time has come that like the 600 at Balaklava, we were to move into the jaws of death. Some of us would soon have fought our last battle and ’ere the morrow sleep our last sleep. We moved to the right and then forward into a cornfield. Here we must have surprised a line of Federal skirmishers as without firing they rose up, apparently panic-stricken. Some fled precipitately to their rear, while others threw down their guns and ran up to us with arms thrown up, begging for mercy. Beyond the field through which we were passing, directly in front of the 47th, was a heavily timbered wood; on reaching this, we were ordered to advance cautiously as the Federal battle lines were thought to be on an elevation just beyond this wood. Company E (Captain DeWitt Bruyn) was deployed as skirmishers at intervals to cover the front of the regiment. The right of the regiment rested near a public road. A Federal officer, mounted on a fine cream-colored horse, was seen riding along the road approaching our skirmish line, apparently carefully reconnoitering; instantly a shot rang out from the right of our line; the Federal officer, throwing up his arms wildly, fell from his horse. “Oh what a fall!” said the brave but tender-hearted Captain Bruyn. “Yes,” said the skirmisher. “I hated it, captain, but we’ve got to do that way to keep from being done that way.”

Breckinridge’s division formed the right wing of our army. [Brig. Gen. Daniel] Adams’ Louisiana brigade was on the extreme right of our division, the 47th Georgia next to the left of Adams’ brigade. At the farther edge of the wood, our skirmishers met with a galling fire from the enemy’s skirmishers and their batteries opened fire on us in the wood. Moving into the open field, we were in full view of the parked batteries and massed columns of [Union Maj. Gen. William] Rosecrans’ left wing. The order was given to charge after our first volley and with fixed bayonets we swept into the field. Under the terrible fire of grape, a regiment on the immediate left of the 47th gave way and fell back into the woods; this caused some confusion in our brigade and for a short time the 47th was halted in the open field under a fusillade of shot and shell from the batteries and rapid fire from the infantry. The brigade of Louisianans, unaware of this break on their left, swept on and up to the guns in their front. Seeing that the regiment on our left did not rally and that Adams’ brigade was being cut to pieces on our right, our regimental commander ordered the 47th to charge. Into the crash and smoke the 47th dashed, but too late; troops could not live in such a fire. The large bay horse of Gen. Adams dashed back through the lines, riderless. Adams was down and his gallant men strewed the ground. The gallant Louisiana brigade was almost annihilated.

The remnant of that splendid command and the 47th Georgia were hurled back, broken and bleeding, and Breckinridge’s whole division, defeated and crushed, fell back in disorder. In this first charge on Sunday morning, the 47th lost in killed and wounded two officers and 74 non-commissioned officers and privates. The whole division sustained heavy losses.

During some time of our unsuccessful assault I was for a few minutes “hors de combat,” and utterly unconscious of all surroundings. When the color-bearer Jack Newberne fell clutching to his brave, broad bosom the flag, I caught it up. The Federal batteries were firing at very short-range grape, shrapnel, and shell, the shells exploding above and around us. One of these exploded so close in my front that I was thrown down and shocked into insensibility by the force of the concussion. A fragment of the shell shattered the flagstaff just above my handhold. When I recovered consciousness, I was face downward on the field.

I could hear cannon in front of me and cannon in the rear of me. I quickly concluded that those nearest must be the Federal batteries so I began to crawl in an opposite direction.

Reaching the woods, I saw our troops forming into battle line. Shot and shell were hurtling around and above, and our batteries to the left were replying hotly. Officers were rallying their shattered commands in an excited manner. Rejoining my command, I found my regiment apparently more demoralized than I had ever seen it. This gave me great concern and mortification and I determined to remain with them as long as I could stand, though I was by this time suffering severely with racking pains in my head.

Rallying and reforming, we were ordered to rest in line while other troops came up. We were held idle for fully two hours. It is a severe strain on troops to keep them on the edge of a battlefield, within hearing of the fray and range of fire.

At about 4 p.m. came the order, “Fall in and be ready to move quickly to the left.” We stood in line awaiting the passage of some batteries to the left, where the battle was terrific and into which I knew we were going.

The artillery out of the way, we began as one to move at quick time to the left. We swept around almost at a right angle nearing the Chickamauga River, halted, fronted, and double-quicked forward through a wood bordering the stream. There, we formed our batteries, guns unlimbered, loaded, pointed, and gunners standing with lanyard in hand, ready to fire. Close behind was a line of infantry standing with fixed bayonets. Our front line was being pressed slowly backward by overwhelming numbers, but they were stubbornly fighting over every inch of ground, giving way only as they were pressed. They were [Maj. Gen. Patrick] Cleburne’s regiments, no better than which ever marshaled on any field on earth. We could hear the cheering of the men engaged and knew by experience how the battle went. Now the fierce yell of the Confederates told of their onslaught as aggressors; then the hoarse hurrahs of the Federals told of their forward movement. We were to hold our fire until our engaged line had fallen back and was safe in the rear, then at the first cannon broadside, we were to deliver our fire and charge everything in our front with the bayonet.

Never through my four years of service did I experience such suspense, subdued excitement, intense anxiety, fearful anticipations, and prayerful hope as in those 15 minutes of waiting. I knew that victory was trembling in the balance and upon us devolved the great responsibility of turning the mighty tide of battle. For two whole days the battle had lasted, fought with skill, valor, desperation, and ferocity and now the critical moment had come which was to decide for the one victory, for the other defeat. Generals rode back and forth waving high their swords and exhorting their men for God’s sake to stand firmly and at the word of command to charge and let nothing between heaven and earth stay them. A general officer rode at full speed up and down his line with plumed hat held high on the point of his sword inciting his command to the greatest enthusiasm. The troops caught the spirit of their leaders and panted in suspense for the movement of action; in fact, it was difficult to restrain and prevent them from singing out in their Rebel yell and dashing pell-mell into the smoke-enshrouded fray in front.

I had scarcely regained my place when our front line came back and fell in at our rear. They came in perfect order and more defiantly than I ever saw troops fall back, for they would face about, fire, yell, and load again. Seeing our line, they wanted to rally and charge again, but the men were exhausted. Many of them fell, pitching forward like wounded or dead. Others would fall to a sitting posture and then collapse backwards to the earth. Then could be heard the loud hurrah from thousands of throats and came the lines of blue. Officers on rearing steeds waved their swords gallantly and cheered their columns on. On our side was a deathly stillness—silent as the soundless crags.

I

nto the open, suddenly, the Federals were confronted by our lines; their cheering died in their throats and for an instant, they halted in startled surprise. In that instant, there rang out the command “Fire!” And as if a thousand thunderbolts from heaven, our cannon crashed and our rifles rang, and then from 10,000 throats rang out the Rebel yell and our double line of gray dashed forward with the bayonet. The blue columns wavered, delivered a straggling fire, then broke and fell back in confusion and disorder, a few surrendering, but the greater number fleeing to their rear, many of them throwing down their arms and stripping off their accoutrements. Some of their officers acted magnificently and displayed great gallantry in their efforts to rally their shattered columns. Our line swept forward not waiting to load and the rout became general. Rosecrans’ splendid army, all save [Maj. Gen. George H.]Thomas’ corps, was beaten, routed, and in full retreat at sundown of that fatal Sabbath day. We were in full possession of the field and of the thousands of dead and wounded of both sides. Such a sight as I witnessed in the flight of those broken columns of the finest soldiers of the Federal army—grand, glorious, and magnificent to me then—is seldom seen in life. I pray God that it may never again be seen in this nation.

Daniel Masters studies the Civil War by journeying through the libraries, historical societies, museums, cemeteries, back roads, and forgotten spaces of Amer-ica. His blog (dan-masters-civil-war.blogspot.com) captures the results of those journeys in the form of battle narratives written predominantly by Ohioans. This story appeared in the March 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.