THE STORY IS TOLD in various versions but they all go something like this:

Henry Ford is on a camping trip with his famous friends—Thomas Edison, the great inventor; Harvey Firestone, the rubber baron; and John Burroughs, the bestselling nature writer—and they encounter a Model T Ford driven by a backwoods hick. Ford tells the hick that he created the Model T, and he introduces his friends: “This is Thomas Edison. He invented the light bulb. This is Harvey Firestone. He made the tires on your car. And this”—and then the hick, looking skeptical, points at Burroughs, whose long white beard hung to his chest, and says, “I suppose you’re going to tell me this guy is Santa Claus.”

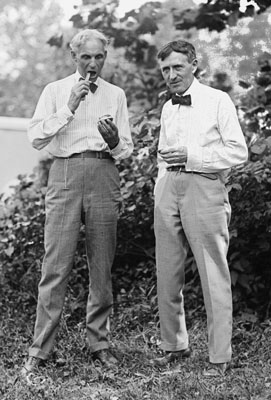

It’s a good story—probably too good to be entirely true—and the reporters and biographers who repeat it never quite agree on where or when it supposedly occurred. But it’s based on an intriguing fact: Nearly every year between 1914 and 1924, Ford and his famous friends did go camping together. They jokingly dubbed themselves “the Four Vagabonds,” and their journeys were a uniquely American combination of back-to-nature vacation, intellectual colloquium and shameless publicity stunt.

Over the years, the Vagabonds voyaged through the Everglades, the Appalachians and the Adirondacks—and each man took on a distinct duty. Edison was the navigator, riding in the lead car with a map on his lap, guiding the caravan and usually choosing the most rutted, bone-rattling dirt roads he could find. Firestone was the commissary officer, supplying the food and the chefs who cooked it. Burroughs led nature walks, identifying plants and birds. Ford was, appropriately, the mechanic, fixing the cars that broke down, which happened frequently. He also organized contests to determine the best tree-climber, the best wood-chopper, the best stream-jumper—and he usually won.

“Mr. Ford, when he is out of doors, is just like a boy,” Firestone wrote. “He wants to have running races, climb trees, or do anything which a boy might do.”

Ford also loved practical jokes. On one trip, he convinced the cooks to slice wooden tent stakes into thin strips and boil them in the soup, just so he could watch Firestone, who was proud of the gourmet food he provided, chomping into them.

Henry Ford, the dynamo behind the Four Vagabonds, was a prodigy of energy. By the time he began organizing the camping trips in 1914, Ford, then 51, had designed the most popular car in America—the Model T—created the modern assembly line and become a folk hero by paying his workers the generous sum of $5 for an eight-hour day. He was also an avid collector of everything from antique farm tools to famous friends.

His most famous friend was Edison, the genius behind the light bulb, the phonograph and the movie camera. As a young man, Ford worked for Edison’s company and Edison encouraged his experiments on a gasoline-powered automobile. When those experiments paid off, Ford rewarded his mentor by loaning him money to rescue his ailing businesses.

“Edison is easily the world’s greatest scientist,” Ford wrote. “I am not sure that he is not also the world’s worst businessman. He knows almost nothing of business.”

John Burroughs was also a mentor to Ford. Nicknamed “the Grand Old Man of Nature,” Burroughs was a famous conservationist who camped with Teddy Roosevelt, and a best-selling author who hobnobbed with Walt Whitman and Oscar Wilde. Ford, an avid bird watcher, was a fan of Burroughs’ writing. When Burroughs grumbled in print that the noisy, smelly automobile was ruining Americans’ appreciation of nature, Ford promptly sent a free Model T to the naturalist, with a note suggesting that it might help him reach scenic places easier. Burroughs enjoyed the car, and the two men became friends. In 1913, they traveled to Walden Pond, where Burroughs, then 76, taught Ford about birds and the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

“No man could help being the better for knowing John Burroughs,” Ford wrote. “He loved the woods and he made dusty-minded city people love them, too—he helped them see what he saw.”

Burroughs was equally laudatory about Ford: “He looks like a poet and conducts his life like a philosopher. No poet ever expressed himself through his work more completely than Mr. Ford has expressed himself through his car.”

In 1914, Ford invited Burroughs to join him on a trip to visit Edison at the inventor’s winter home in Florida. From there, the three men—accompanied by Edison’s wife and Ford’s wife and son—went camping in the Everglades. Burroughs loved the exotic flora and fauna—he said the Everglades reminded him of Hawaii and Jamaica—and the three men vowed to camp together again.

In October 1915, Edison was honored at San Francisco’s Pacific International Exposition. Ford attended, accompanied by Firestone, the Akron rubber manufacturer who supplied him with tires. After the festivities, the three men traveled around California, stopping to visit Luther Burbank, America’s most famous horticulturalist.

Shortly after that trip, Ford embarked on another journey—a quixotic attempt to end World War I. The war had been raging since August 1914, although the United States was still neutral. Ford thought the carnage was foolish—which was undeniably true—and he decided to sail to Europe to negotiate a peace treaty. He chartered a steamship and invited prominent Americans, including Edison and Burroughs, to accompany him. Nearly all of them declined, including Edison and Burroughs. So Ford filled his “peace ship” with an eclectic collection of pacifists, suffragists, clerics and college students—or as one newspaper called them “every crackpot and nut in the country.” On December 4, 1915, as a band played “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier,” the ship set sail. Two weeks later, when it reached Norway, the pacifists were fighting over ideological differences and Ford was locked in his stateroom, claiming he had a cold. He spent a week in Europe but failed to end the war, so he sailed back home, where newspapers mocked him unmercifully.

Shortly after that trip, Ford embarked on another journey—a quixotic attempt to end World War I. The war had been raging since August 1914, although the United States was still neutral. Ford thought the carnage was foolish—which was undeniably true—and he decided to sail to Europe to negotiate a peace treaty. He chartered a steamship and invited prominent Americans, including Edison and Burroughs, to accompany him. Nearly all of them declined, including Edison and Burroughs. So Ford filled his “peace ship” with an eclectic collection of pacifists, suffragists, clerics and college students—or as one newspaper called them “every crackpot and nut in the country.” On December 4, 1915, as a band played “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier,” the ship set sail. Two weeks later, when it reached Norway, the pacifists were fighting over ideological differences and Ford was locked in his stateroom, claiming he had a cold. He spent a week in Europe but failed to end the war, so he sailed back home, where newspapers mocked him unmercifully.

When an underling informed Ford that his peace crusade had cost him $465,000, the auto baron tried to look on the bright side. “Well,” he said, “we got a million dollars worth of advertising out of it.”

Perhaps the peace ship fiasco temporarily cured Ford of his wanderlust: He did not accompany his fellow Vagabonds in the summer of 1916, when they went camping in the Adirondacks in New York and the Green Mountains of Vermont.

In Ford’s absence, Edison led the expedition and set the tone, which was exceedingly casual. The inventor, then 69, would study his map and select a route but change it repeatedly along the way, usually detouring onto ever rockier roads, claiming that he enjoyed the “shaking out” of being bounced around.

“We never know where we are going,” Firestone joked, “and I suspect that he doesn’t either.”

Edison loved escaping the bonds of what he called “fictitious civilization,” and he enjoyed sleeping on the ground in his clothes. “He is a good camper-out, and turns vagabond easily,” Burroughs wrote. “He can rough it week in and week out and be happy.”

Embracing his inner hobo, Edison announced that they should all stop shaving during the trip. Firestone, a more fastidious fellow, found Edison’s edict difficult to obey. After a few days, he snuck off to a hotel, seeking a bed, a bath and a shave.

“You’re a tenderfoot,” Edison grumbled when Firestone returned. “Soon you’ll be dressing up like a dude.”

In 1917, the year the United States entered World War I, the Vagabonds canceled their vacation. But they resumed the outings in 1918, meandering through the Appalachian Mountains in Virginia, West Virginia and North Carolina. They traveled with a cook and several assistants, including a photographer from Ford’s public relations department, who provided newspapers with carefully posed “candid” shots. The Vagabonds tooled down country roads, followed by three trucks stuffed with food, camping equipment and the batteries Edison used to power lights in each tent.

“It often seemed to me,” Burroughs joked, “that we were a luxuriously equipped expedition going forth to seek discomfort.”

After a day’s bone-rattling drive, Edison would pick a place to stop and then somebody—usually Ford—would ask a farmer for permission to camp on his land. They’d stay two or three nights

After a day’s bone-rattling drive, Edison would pick a place to stop and then somebody—usually Ford—would ask a farmer for permission to camp on his land. They’d stay two or three nights

at a spot. During the day, they’d hike through the woods, with Burroughs identifying flowers and birds, while Edison sliced into plants, searching for sap that might become an ingredient in synthetic rubber Firestone could use in his tires. When they came upon a stream, Ford and Edison liked to calculate how much hydroelectric power it could generate.

In the afternoon, the Vagabonds moseyed back to their campsite to eat an elaborate dinner prepared by Firestone’s cooks. Then they’d build a big fire and sit up late, talking about the war, politics, business and science.

“Around the campfire, we drew Edison out on chemical problems, and heard formula after formula come from his lips as if he were reading them from a book,” Burroughs wrote. “It was easy to draw out Mr. Ford on mechanical problems. There is always pleasure and profit in hearing a master discuss his own art.”

One night, the talk turned to books, and Edison announced that the world’s greatest works of literature were “Evangeline” and Les Misérables. When Firestone disagreed, touting Shakespeare, Edison suggested that the Bard’s plays would be better if somebody translated them into “common, everyday speech.”

Perhaps he was joking. Edison had a wicked wit that cracked up his pals. “His humor is delicious,” Burroughs wrote. Ford liked to tell jokes, too, but he quickly realized that his delivery wasn’t nearly as good as Edison’s. Later, back in his office, Ford instructed his secretary to type up his favorite jokes, so he could give them to Edison to deliver on future trips.

The Vagabonds returned to the Adirondacks in 1919, this time in a caravan of 50 cars and trucks, which included the usual retinue of cooks and helpers, plus a posse of reporters, photographers and newsreel cameramen. The Vagabond vacations had become media sensations, which Firestone and Ford were eager to exploit. Firestone decorated his trucks with signs reading “Buy Firestone Tires!” and Ford dealerships along their route announced special sales. One night, the Vagabonds invited a New York Times reporter to hang around the campfire and record their palaver.

“I see where there’s a big rumpus over the cost of living,” Ford said, perusing a two-day-old newspaper.

“It’s a great problem,” said Burroughs. “We used to buy things in bulk. They were cheap then. Nowadays, everything comes wrapped up in fancy packages.”

Firestone suggested the problem was too many middlemen between the producer and the consumer. Ford said that food cost too much because farmers were still using horses instead of tractors.

“Eliminate the horse, the cow and the pig,” Ford demanded.

“What are you going to do for meat?” asked Edison.

“You don’t need it,” said Ford. “The world would be better off without meat. It’s 70 per cent ashes anyway. Milk can be manufactured chemically.”

“You can’t eliminate horses and cows and pigs,” Burroughs protested.

Ford said he could, and promised that he would, replacing them all with machines within a few years. “I will cut down the work on a farm to 20 days a year,” he boasted. “Twenty days a year is all a farmer needs to work.”

But the Times reporter wasn’t around when Ford, a notorious anti-Semite, started ranting about Jews. “Mr. Ford attributes all evil to the Jews,” Burroughs wrote in his diary. “The Jews caused the war, the Jews caused the outbreak of thieving and robbery all over the country, the Jews caused the inefficiency of the Navy of which Edison talked last night.”

When Ford cited Jay Gould, the shady financier, as an example of evil Jews who controlled Wall Street, Burroughs said he’d been a childhood friend of Gould, who happened to be a Presbyterian.

Touché! Though his mind was sharp, at 82, Burroughs was growing frail. The following summer, he was too feeble to travel, so the other Vagabonds and their wives visited his Catskills farm, and stayed in hotels instead of camping. Burroughs died in March 1921, and that summer his friends went vagabonding without him.

They camped in the hills of Western Maryland, where they were joined by a new Vagabond—President Warren G. Harding, who arrived at their campsite trailed by a gaggle of White House aides, Secret Servicemen and photographers. Harding chewed tobacco, chopped firewood, rode a horse and hiked along Licking Creek, reminiscing about the swimming holes of his boyhood. When he noticed Edison napping beneath a tree, the president placed a newspaper over the great man’s head. “We can’t let the gnats eat him up now, can we?”

That night, Harding sat around the campfire until 2 a.m. and slept in a tent. The next morning, he attended an outdoor memorial service for Burroughs, and then returned to Washington. The other Vagabonds kept traveling, camping out for two weeks.

“I like to get out in the woods and live close to nature,” Edison told reporters. “Every man does. It’s in his blood. It is his feeble protest against civilization.”

The trip in 1921 was the last Vagabond jaunt that involved living close to nature. In subsequent years, luxury replaced camping. In 1923, the friends sailed the Great Lakes in Ford’s yacht. In 1924, they checked into the Wayside Inn, an 18th-century hotel in Sudbury, Mass., that Ford had recently purchased. From there, they drove to Plymouth, Vt., to visit Calvin Coolidge, who had become president when Harding died. Coolidge, known as “Silent Cal,” was running for reelection.

“Will Coolidge be elected?” the inevitable mob of reporters hollered to Edison.

“Sure,” Edison replied, “if he doesn’t talk too much.”

Coolidge cracked up.

That was the Vagabonds’ last trip. The old friends were getting older and their camping trips had lost pizzazz. Some historians suggest that the trips helped create a new American lifestyle—strapping the kids into the family car for a camping vacation. Others enjoy pointing out a delicious irony: Ford and Edison used the trips to flee from the pressures of a modern civilization that their inventions had helped to create.

For the rest of his life, Ford enjoyed telling a story about the camping trips: Driving his Ford through the countryside, he encountered a farmer trying to fix his broken-down car, which wasn’t a Ford. Without identifying himself, Ford pulled out tools and spare parts and repaired the farmer’s vehicle.

“What’s the charge?” the farmer asked.

“Nothing,” Ford replied.

The farmer insisted on paying, and offered $1.50.

Ford refused. “I have all the money I want,” he said.

The farmer looked him over skeptically. “Hell,” he said, “you can’t have that much if you drive a Ford.”

It’s a good story. It might even be true.

Peter Carlson is the author of Junius and Albert’s Adventures in the Confederacy: A Civil War Odyssey.

This article originally appeared in the August 2013 issue of American History magazine.