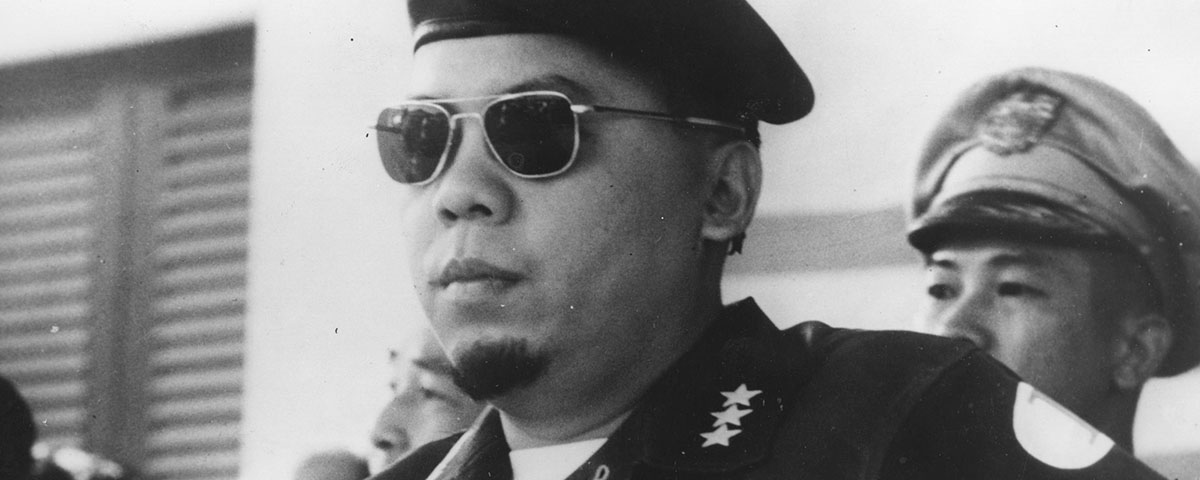

General Nguyen Khanh sheds light on Saigon’s swirling world of coup and counter coup

“This Khanh is the toughest one they got and ablest one they got,” President Lyndon B. Johnson told a reporter in 1964. LBJ’s Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara called General Nguyen Khanh “the George Washington of Vietnam.” Whether either glowing assessment was true or not, one thing is for sure, General Khanh was a central figure in the tumultuous and coup-riddled years leading up to America’s long and disastrous war in Vietnam. Little recalled today among the familiar and often notorious South Vietnamese leadership from Diem to Ky to Thieu, Khanh was in the thick of the intrigue, both plotting alongside Americans as well as ultimately becoming a coup victim himself.

As a young man, Khanh fought the French colonial army with the Viet Minh. However, he later graduated from the French military academy at Da Lat, Vietnam, and then studied at St. Cyr, the French equivalent of West Point. In 1957 he graduated from the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., and from there went back to his homeland and was soon enmeshed in the power struggles between the often corrupt elite.

Just three months after participating in a U.S.- backed coup that toppled President Ngo Dinh Diem on November 2, 1963, while commander of II Corps, Khanh and General Tran Thien Khiem seized control of the Military Revolutionary Council on January 30, 1964, prompting the praise from Johnson and McNamara. Initially, he kept General Duong Van Minh as figurehead chief of state, but in August 1964 he assumed Minh’s position. Generals Le Van Kim, Tran Van Don and others were arrested by troops loyal to Khanh.

Khanh’s place at the pinnacle of power was brief, due to Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge’s departure to pursue the U.S. presi dency as a Republican Party candidate. Lodge was replaced by Maxwell Taylor, who previously had clashed with Khanh. However, the U.S. Embassy, the CIA station chief and General William Westmoreland were greatly concerned about Khanh’s safety and did not want a replay of the Diem coup. Both Ambassador Taylor and Westmoreland knew that LBJ would hold them responsible if, like Ngo Dinh Diem and his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu, Khanh was assassinated. Therefore, after being deposed by the U.S.- supported coup, Khanh was made Ambassador At Large and allowed to depart Vietnam. After 12 years in exile in Europe, Khanh, with his wife and six children, went to the United States in 1977.

By any measure, Nguyen Khanh, born a Buddhist in a small village in the Mekong Delta, has led an extraordinary life, both shaping and being buffeted by the fortunes and failures that have comprised the last 50 years of Vietnam’s history. He served as head of state and prime minister, commander of the army, chief of staff of the Joint General Staff, and at different times commander of I, II and IV Corps. Even today, Khanh remains very active in the political life of Vietnam’s exile community.

In an interview with veteran journalist Edward Rasen, Khanh reveals intimate insights into the leaders and the intrigues—and the U.S. role in those intrigues—that shook Vietnam in the early 1960s. Still reticent about many details, Khanh prefaced his comments to Rasen by saying: “It is very dangerous what I am doing now, talking to Americans without knowing exactly the meaning of the American war. But, I will try to do my best. I am a friend of America.”

Vietnam: Did President Diem have a plan to win the war?

Khanh: No. I wrote one for him. After being at Fort Leavenworth for the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, I returned to Vietnam. President Diem assigned me to the Presidential Palace where I created the Office for National Defense—the complete national defense, not just the military but the economy, security of the people in the countryside, foreign relations, everything.

Diem always worked long hours. One night at 2 in the morning he called me at home and asked me to visit him in order to discuss the plan to defend Vietnam. He was not married. I was married. I was sleeping with my wife. I did not want to go to work, but I had to go.

I explained to Diem how to win the war. I told him we must prepare the defense outside Vietnam. He understood that. I asked him to make preparations and he agreed. But, Diem was not a military man. I talked with Diem and especially his brother Nhu, chief of national security, about defense of our country. I thought we had to militarily defend Vietnam in Laos by occupying the Plateau of Bolovens, the Saravane-Attopeu front and also along the north national road Number 9 from Quang Tri to Tchepone, Laos.

Did Diem’s brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, have a military mind?

No. Ngo Dinh Nhu had a political mind. Different, devious. He mixed politics with other things to his advantage.

Did Nhu want to be prime minister?

Maybe. But, certainly, 100 percent, Madame Nhu wanted to be first lady. In order for her to be first lady, Nhu must be president. The Republic of Vietnam constitution was written so that Diem and subsequent presidents only could serve three terms. So they were preparing Nhu. She had big ambitions.

How were you involved in the coup d’etat against President Diem during 1963?

The coup that Generals Minh and Don made with the CIA. I had a friend, Lou Conein [CIA officer, Saigon station], who was close because his wife was half-Vietnamese, half- French. We were close because he spoke French and Vietnamese. He visited me maybe two weeks before the coup. He did not come talking about the coup even though he knew. He said a French sentence, “Ne pas dormer sur les deux oreilles”—“Be careful not to sleep on both ears.”

The day before the coup at 10 o’clock in the morning, General Duong Van Duc, my friend and former classmate, flew from Saigon to visit me in Pleiku. He said he represented some generals in Saigon who don’t like things going on because it could go like General Charles de Gaulle is talking. [Charles de Gaulle advocated Vietnam unification, and the election of one leader as called for in the Geneva Accord of 1954.]

They were worried because some Vietnamese generals were still involved with the French. Even Tran Thien Khiem was in the Service Historique, which is the Historical Record Service of the Army Forces, similar to the CIA. Also, General Tran Van Don. General Duong Van Minh, the other coup leader, had a brother who was a Viet Minh officer, a major, from Hanoi, living in his house for six months. All that was true. And Mai Huu Xuan, chief of police during the French time, was involved as the command chief. He had been in charge of controlling the nightclubs and prostitutes for the French. And Prime Minister Nguyen Ngo Tho previously was a French civil servant.

I was not the coup author, even though many people say I was. I accepted the generals’ invitation. General Duong Van Duc went back to Saigon at 11 o’clock. I wanted to learn what the Americans were thinking. The coup could not succeed without direct intervention of the Americans. I sent Colonel Jasper Wilson to Saigon to check with the U.S. Embassy and General Paul Harkins at MACV. He was a friend.

I departed Pleiku for Saigon on the last flight at 6 o’clock in the evening and arrived at approximately 8 o’clock. I met with some generals: Tran Thien Khiem, airborne and others. Colonel Wilson brought us to what the Americans called the “White House” and we called the “Maison Blanche.” It was for colonels and above.

The morning of the coup I went by the General Staff headquarters. I saw the guards but nothing happening. So, I went to the airborne units, my old units. I had built the paratrooper branch. I was the first commander, so I went back to them.

Did you know about the plan to assassinate Diem and his brother?

Minh and Don lied to me. I did not want to kill Diem and Nhu. That is the condition I demanded for supporting the coup. But they lied to me. The day after the coup they had a big reception, and I did not attend. I was the only invited general that did not attend. They knew I was against the assassination of a civilian leader by the armed forces. It is the same as gangsters with guns. I did not agree and still cannot agree. After the coup, they were supposed to make me commander of III Corps, but then Minh broke his promise.

What was your relationship with the United States after you took control of Vietnam on January 30, 1964?

The first ambassador I worked with was Henry Cabot Lodge. We worked hand in hand. I remember one day he came to see me during the first week I was in power. I said, “Mister Ambassador, the French want to kill me, assassinate me in Tay Ninh, while I attend a ceremony with the Cao Dai.” The Cao Dai still had some connection with the French. His answer was, “If so, let’s go together.” And he did go with me. We were like brothers, closer than combat soldiers.

When Lodge returned to the United States to become a presidential candidate during 1964, he was replaced by General Maxwell Taylor. I had asked Washington to send me another Henry Cabot Lodge, someone who knew the politics and problems we faced. But Washington sent me an “uncertain trumpet.” Taylor was a prominent military leader who had been rescued by President Kennedy after a fatal career under President Eisenhower. But, he did not know very much about the situation in Vietnam or the Vietnamese people and their culture. Also, I can frankly tell you that he did not know anything about revolutionary war. How was I supposed to work with him?

You ultimately had some advice to give to Ambassador Lodge?

After I departed Vietnam near the end of February 1965, two months later Taylor was removed as ambassador. When Lodge was asked by President Johnson to return as ambassador for the second time, he invited me to visit him at his house in Massachusetts. I stayed as a guest for five days, and we talked very much about Vietnam. He asked what I thought he should do. I said he had to respect the Vietnamese people. “You cannot go there like a boss, like Maxwell Taylor.”

When you attempted to negotiate with the Buddhists, advisers to President Johnson accused you of being in favor of peace, and the Dai Viet political party accused you of being pro-Communist.

I will tell you about the situation in Saigon. When you did not appease certain groups, they called you a Communist. Who was it in the United States that practiced that tactic? Joe McCarthy? We had the same people in Vietnam. Anyone you disagree with, just call him a Communist. It was very demoralizing and counterproductive. The accusations were unfair and destructive, especially when you are trying to build a representative government.

Why was Ambassador Maxwell Taylor angry with you during December 1964, after you dissolved the High National Council?

I knew Taylor was angry about the dissolution of the Council. But the military leaders created the Council and gave the civilians certain powers. When General Duong Van Minh issued an order for military officers of a certain age to be retired like in the U.S. Army, the Council said “no.” So I enforced the order. The Council overruled me. They decided Minh and I made the rule because we wanted to eliminate enemies. I said they were wrong in doing such. They were not elected by the people. They did not ask me or other military leaders why we made the rule.

Taylor was angry because he and other people, including some Vietnamese politicians, thought all orders should originate from the U.S. ambassador. I did not think so. We were fighting with the Americans and the Americans were helping us. We were thankful about that. We worked together. But, the Americans cannot be both allies and rulers. So, the conflict between Taylor and me was about that. He had some habits from serving in occupied Japan and Korea. Then he came to Vietnam and acted the same way, like a military ruler.

Why did you meet on February 8, 1965, at Camp Holloway with Ambassador Taylor, National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy and General Westmoreland?

Camp Holloway had been attacked by Communist guerrillas, and at the time it was a big loss for the United States. More than 100 Americans were killed or wounded. At the time I never slept in Saigon as I was more confident with the armed forces because of the political climate in Saigon, where you can find mistrust and betrayal. I slept at different corps headquarters, with my personal headquarters in the air.

The morning of the attack against the camp, I flew from Qui Nhon to Pleiku. I had been commander of II Corps, which was headquartered in Pleiku, so I knew the area and the problems. After landing, I met with our local military officers. Then McGeorge Bundy, Ambassador Taylor and General Westmoreland arrived from Saigon for the same purpose. Bundy was visiting Vietnam for a few days and was scheduled to depart that day. We had a meeting and exchanged ideas. It was in Westmoreland’s C-123 twin-engine cargo aircraft. It had a small area with maps and chairs. We decided to retaliate for the camp attack by bombing North Vietnam. Bundy promoted the idea. Ambassador Taylor agreed and so did I.

But, I asked for participation by the Vietnamese Air Force. I said the United States cannot alone bomb North Vietnam. We have to go with the United States, even if only with a couple of fighters, but we must be present. They agreed. That is how South Vietnam flew on the first bombing missions with the Americans. And Nguyen Cao Ky was there. I gave him orders to go—but I told him to be careful. I did not want to lose my Air Force commander in the first attack!

When did you become aware that Taylor and Westmoreland were promoting a coup d’etat to eliminate you?

I call the coup d’etat against me the double coup. The first was the failed coup led by Colonel Pham Ngoc Thao. The second was by Vice Air Marshal Nguyen Cao Ky and General Nguyen Van Thieu, the leaders of the so-called “Young Turks,” backed by Ambassador Taylor and General Westmoreland. The trouble did not start in Vietnam, despite what the Americans said.

Before the incident at Camp Holloway, I had a meeting at Bien Hoa air base with Vietnamese general officers. I know what happened there. I regret to say to you that it is true. It was the start of the second coup against me with the participation of Ambassador Taylor and General Westmoreland. MACV even sent jet airplanes to move Vietnamese commanders from Hue and Da Nang to Bien Hoa while I was in Pleiku. They had to move very quickly while I was in the field. The Americans arranged a vote of no confidence, even though a vote of no confidence was not an official act in the constitution. Then, they encouraged Ky and Thieu to replace me. I know what happened. It is a very long story about the coup against me.

I took off from Tan Son Nhut airport while tanks began occupying the other end of the runway. I flew to Cap Saint Jacques [Vung Tao], which was my second headquarters with a complete communications system. I sent a message to the nation while in the air via Radio Soc Trang, presenting the real situation of the coup executed by the Young Turks, with the help of Taylor and Westmoreland. Then I traveled from Cap Saint Jacques to Nha Trang because I wanted to meet with the commander of the 23rd Division. Also, I was friendly with the commander of the Vietnamese Special Forces, which had headquarters in Nha Trang.

When I landed in Nha Trang, I knew an attempted coup was brewing. Colonel Wilson of the U.S. Army was with me. He was my permanent American aide. He was the only American with me. He tried to get my airplane refueled, as did I. The Vietnamese Air Force [commanded by coup co-leader and Vice Air Marshal Nguyen Cao Ky] refused me. The Americans told Colonel Wilson that it was too dark and we had to wait until morning. The situation was suspicious. I did not comprehend who was the enemy. We snuck away.

After we departed Nha Trang, I saw two fighter aircraft circling. They had orders to destroy my aircraft. It is true. Phung Ngoc An, who was combat operations commander in II Corps for the Vietnamese Air Force says he was ordered by Nguyen Cao Ky to shoot down my aircraft. I told Captain Doan, my pilot, to be careful. He had flown many times over North Vietnam, dropping Vietnamese Special Forces for CIA missions. So he flew very low to Da Lat. But, we could not see the Bao Dai airfield near the former Bao Dai palace. We flew to the Lien Khoung airfield about 15 or 20 miles from Da Lat, where Air Vietnam and military aircraft landed. But we could not see it. Then we flew to Ban Me Thuot, but we did not see anything.

I asked Doan, “What do we do now?” He said, “Very little fuel, so soon we must glide.” I told him to proceed to Phan Rang, 50 miles south of Nha Trang and three miles in from the coast. On the way from Ban Me Thuot to Phan Rang, we had to fly past Da Lat. We saw a hole in the clouds. We descended and saw the Da Lat airfield. We stopped just two meters from the end of the airfield. We could not move because we were out of fuel. Then we went to my house.

Did Taylor or General Westmoreland ever call you?

No, those are false rumors. And I did not call Ky or Thieu. After a few days, Ky and Thieu sent General Linh Quang Vien to negotiate with me. He was a friend and still works with me. I said, “No negotiations, I will leave the country.” I knew the United States was behind the coup.

The United States sent a U.S. Army plane to fly me from Da Lat to Cap Saint Jacques. My mother lived in Cap Saint Jacques and I wanted to say goodbye. After visiting her, Colonel Wilson asked, “Now where do we go?” I said, “Saigon.” Wilson said, “You know better than me that this plane cannot land there.” I knew that Tan Son Nhut airport must be occupied by rebel South Vietnamese troops.

So I decided to fly from Cap Saint Jacques to my house in the headquarters of the Vietnamese Navy on the Saigon River. I had a house, the prime minister’s house, near the headquarters of the Navy, with a large area where you could land a small aircraft. Then the U.S. protectors arrived. U.S. helicopters arrived at Cap Saint Jacques.

Colonel Wilson told my plans to a U.S. Army one-star general who became upset and said, “No, no, colonel we don’t want to be involved.” I did not say anything. Wilson took a paper from his pocket and showed it to the general. He read it… and said, “Yes, sir.” The orders must have come from MACV, not from Wilson.

Did you know that General Huynh Van Cao was spying on you for the CIA?

I did not know for sure until my end as leader of Vietnam. Sometimes you never know for sure if someone is on the CIA payroll. Sometimes it is the wife that is on the payroll. The CIA is very devious. I had a feeling about that then. I had our intelligence service investigating secrets being leaked. I did not have proof but I had indications. Guys like Cao, I do not understand at all.

What do you think about Nguyen Cao Ky?

He was my baby. I pushed his military career. I will not give my candid opinion here. It will look like I attack somebody who is not in front of me. But, he is not a very good guy either in fighting the war in Vietnam or now, regarding the new U.S. policy for Vietnam.

What did you think of General William Westmoreland?

Westmoreland, when he came to Vietnam, was a three-star general. Previously, I had been chief of staff of the Joint General Staff [equivalent to the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff]. Westmoreland tried to do his best but, he did not understand the problems. The containment strategy was not applicable in Vietnam. He should have asked Washington to change it, rather than constantly asking for more troops.

Do you believe the problem was greater than General Westmoreland?

The American policy was no good. They did not know anything about a peasant-based guerrilla war. Also, many Vietnamese in Saigon were not working for their country—they were working for their pockets. So, we lost South Vietnam. I am not surprised that it was lost. But, I regret it very much.

Many mistakes were made beyond General Westmoreland. You say you were just bombing the Ho Chi Minh Trail. But, in fact you put bombs everywhere, all over Laos and Cambodia. The United States used more bombs in the Vietnam War than it did during World War II and Korea. You wasted bombs so back home you could spend money to make new bombs. I think it was immoral. You cannot take the lives of people just to solve a political problem. You create more problems. Isn’t it immoral to kill people because you really want to resolve domestic problems, political or economic?

—Edward Rasen Jr. was a combat infantryman and long-range patrol team leader in Vietnam, and producer for ABC News in Vietnam and Cambodia. Vietnam War Secrets, a 10-hour series produced by Rasen, is now available on DVD and has an extensive interview with Nguyen Khanh.