Before World War II, Adolf Hitler and his advisers built a tactical air force—dive bombers, ground-attack mud movers, medium bombers for short-range missions, air-superiority fighters and bomber destroyers. For a long time there were no strategic four-engine, long-range bombers in the Luftwaffe arsenal other than the Focke-Wulf Fw-200C Condor, which was basically an airliner quickly converted for maritime patrol but not particularly suited to it. At least initially, Germany figured it would romp through Europe, invade England and win the war without ever having to deal with the United States.

In 1940, however, Hitler realized he needed a heavy bomber that could reach New York, now that a U.S. presence in the war seemed increasingly likely. Willi Messerschmitt, for his part, had already been tinkering with such a design well before America entered the war in December 1941, despite the fact he’d been ordered to ignore everything but fighter design and production. So at a time when B-17s were already in service and the final wiring was being strung through Boeing’s first B-29 prototype, the so-called “Amerika Bomber” was still only a proposal on paper.

The original proposal stipulated a bomber that could reach New York from Portugal’s Azores, which cut about 800 miles from the round trip, making it a 6,400-mile mission. Portugal was ostensibly neutral, but early in the war Portuguese dictator Antonio Salazar had been friendly with the Germans. That changed in 1943 when Portugal leased a base in the Azores to the Allies.

Focke-Wulf, Heinkel, Horten, Junkers and Messerschmitt were asked to respond to the request for proposals. Junkers, Messerschmitt and Focke-Wulf came up with conventional bomber designs that might well have worked, while Horten suggested a six-jet flying wing and Heinkel wanted to build a piggyback rig on an He-177 that would carry a crewed Dornier Do-217 to the mid-Atlantic, where it would be launched on a one-way mission. Aero engineer Eugen Sänger came out of left field to propose a suborbital quasi-liftingbody rocket ship that would skip along the top of the troposphere at 13,725 mph and drop a single 8,000-pound bomb, perhaps even atomic, on Manhattan.

Heinkel’s piggyback proposal became a nonstarter when the Kriegsmarine announced that it wasn’t about to risk a U-boat to pick up the Do-217’s crew just off the U.S. East Coast, which had been a crucial part of the plan. Certainly the Germans had no stomach for a pure suicide mission, and they realized that the psychological warfare value of such obvious folly was minimal.

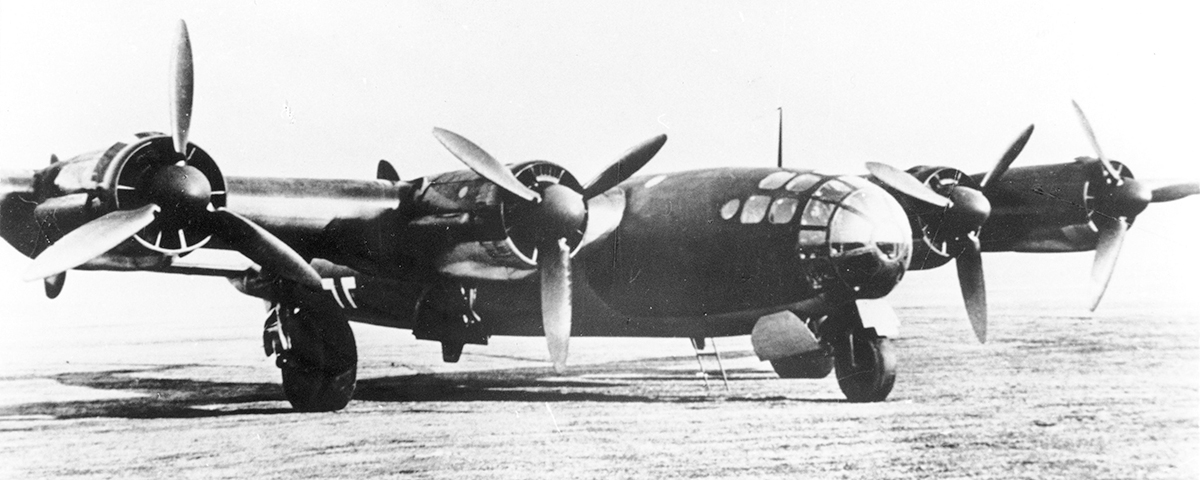

Junkers’ Ju-390 and Focke-Wulf’s Ta-400 proposal were uprated versions of existing designs, and Messerschmitt’s Me-264, thanks to Willi’s head start, was a clean-sheet-of-paper offering that looked as though he’d been given a copy of the B-29’s blueprints. The Me-264 was a mailing-tube-fuselage, four-engine, tricycle-gear heavyweight with a hemispherical, multi-paned glass nose much like the Superfort’s.

The Amerika Bomber proposal was initially somewhat casual, with a number of implicit assumptions—the Azores as a base for one, and a high enough combat ceiling to put the bomber above the reach of U.S. interception for another, so no defensive armament or armor would be needed; drop the bombs from way up in the blue and motor on home. By 1942, it was clear this Hund wouldn’t hunt, so the Reich Air Ministry upgraded the range, gross weight and guns-on-board criteria to the point where it became obvious that six engines rather than four would be needed. Messerschmitt in fact planned to build a six-engine Me-264B but never did, so the Ju-390 remains the largest conventional landplane ever built in Germany. (The Messerschmitt Me-323 Gigant was far lighter, though it had a greater wingspan and length, but that six-engine, fabric-covered, motorized glider was hardly “conventional.”)

The Germans never intended to bomb New York City into oblivion—a mission far beyond the capability of even an armada of slow bombers at the limit of their range, on their own without fighter escort. The Amerika Bomber was intended as a PR weapon, exactly as Jimmy Doolittle’s Tokyo Raider B-25s had been. And even if bombs did little damage, the threat of long-range bombers would force the U.S. to expend effort on anti-aircraft defense with guns and interceptors that otherwise would have gone to war zones. The picture would have changed drastically, of course, if Germany’s attempt to develop an atomic bomb had succeeded.

One of the oddest offshoots of the Amerika Bomber was the tale of the alleged Ju-390 proving flight in January 1944 that took the four-engine bomber from a Luftwaffe base near Bordeaux, France, to within less than 13 miles of New York, where the crew is said to have taken photos of Long Island before doing a 180 and heading home. The photos have never been found. Though there is doubtful “documentation” of the flight in the form of postwar interrogations of a few boastful ex-Luftwaffe personnel, it’s hard to believe that anybody would actually have been dumb enough to send a defenseless prototype bomber to within a few miles of Republic’s P-47 factory at Farmingdale and Grumman’s Bethpage base, both on Long Island, and ChanceVought’s F4U swarm at Stratford, Conn., just across Long Island Sound. The Internet continues to perpetuate this urban legend on a variety of WWII fanboy websites, despite the fact that the Ju-390 test pilot’s captured logbook shows the six-engine Junkers was in Czechoslovakia undergoing tests at the time of the imaginary mission, and that the airplane would have had to take off at nearly twice its proven gross weight to carry the necessary fuel.

There are other unsubstantiated, and most likely untrue, accounts of extreme-range Amerika Bomber flights. The second Ju-390 prototype (only two of the type were ever built) supposedly flew from Germany to Cape Town, South Africa, in 1944, but no hard evidence has yet turned up to confirm Junkers test pilot HansJoachim Pancherz’s postwar claim that he made the flight. The sole Me-264 was said to have made a number of nonstop flights carrying VIPs between Berlin and Tokyo, a 5,700-mile trip, but that claim most likely grew out of the rumor that the plane was standing by to carry Hitler to Japan if he’d been unable to quash the “Revolt of the Generals” and had to flee the Claus von Stauffenberg–led plot to kill him.

One last, fascinating mission awaited the Me-264. It was supposed to be turned into a test-bed for a 6,000-hp steam turbine that was fueled with a mixture of pulverized coal and gasoline to spin a single enormous 17½-foot-diameter, slow-turning propeller. Unfortunately for steam junkies everywhere, the airplane was destroyed in an air raid before that could happen.

Originally published in the January 2011 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.