Roy H. Elrod was born in 1919 and grew up on a farm near Muleshoe, Texas, that his widowed mother operated. He managed to save enough money, even during the Great Depression, to attend Texas A&M, but in 1940 he dropped out of college to enlist in the Marine Corps, where he rose through the ranks rapidly. By the time his 8th Marine Regiment was sent to Guadalcanal in November 1942 he was commanding a platoon of 37mm antitank gunners.

As he and his fellow marines moved through the jungles of Guadalcanal on January 15, 1943, Elrod engaged a particularly deadly Japanese machine gun emplacement and disabled it by crawling to the front of the nest and jerking the red-hot barrel out of the enemy’s hands. He then killed both gunners. For his combat leadership, he received a Silver Star and a battlefield promotion to lieutenant colonel.

Elrod’s last and final combat was at Saipan, where he was severely wounded by Japanese artillery fire. He was awarded the Purple Heart for his action there.

Elrod died in 2016 at age 97. The narrative that follows is adapted from Elrod’s posthumously published memoir, We Were Going to Win, or Die There—With the Marines at Guadalcanal, Tarawa, and Saipan (University of North Texas Press, 2017), which was edited by Fred H. Allison, a retired Marine Corps officer who since 2000 has been the Marine Corps’ oral historian.

Nighttime was a spooky time along the perimeter. It could be the blackest black, and the jungle made strange noises with the numerous critters that populated it—big spiders, crabs, and whatnot. There was always in the back of our minds the knowledge that the Japanese liked nothing better than to sneak into a foxhole and cut a marine’s throat. There would be shouting back and forth, mutual insults passed with the Japanese. Of course, their English was very poor. Some might have spoken good English, but all of them had problems with Ls and Rs. For passwords we would try to get a word that had letters that would be difficult for them to repeat. We always had a password and a countersign. I told my men not to fire unless they were certain it was a real threat. To do so gave away our position, and it caused the other marines to awaken and go on alert, thus depriving them of sleep.

I soon discovered that worse than the Japanese were the living conditions on Guadalcanal. We were really living like animals. If it rained, we got wet. If the sun came out, we got dry. If you were close to a river and you could keep from being exposed to sniper fire, we would take a bath in the river. Of course, we watched for alligators and crocodiles. If there was no river, we didn’t bathe. We would be desperate to be clean, though, so if it started raining, and we were clear of snipers, we’d strip, and soap up. If it stopped raining before you got rinsed off, then you just had a layer of soap on you until the next time it rained.

Living on the front line, we had no tents. There was nothing in front of us but the Japanese. We lived in holes, but we dug our holes so when it rained, the water would run to one side. We could [then use] our helmets [to] bail the water out. That kept us from having to actually sleep in the water. That didn’t keep the rain from falling on you. Sometimes we tried to rig a shelter half over the hole but there was no real way to stay dry.

Occasionally, when we would have one of the fold-up stretchers around, I would open one up and sleep on it, and this would keep my body an inch or so above the ground. We all wanted to have as light a load as possible, and so I had a half-blanket. I slept on that and we would usually cover ourselves with a poncho or something to ward off as much rain as possible. We quit trying to stay dry. If you had something that you wanted to keep dry, you’d keep it under your helmet on top of your head. Marines put letters or pictures, or the people who smoked would put their cigarettes there. I never smoked.

It didn’t take long for my marines to get sick. I developed a case of malaria after only about a week…along with dysentery and diarrhea. I remember one night I sat on this box over a slit trench streaming with diarrhea, shaking with malaria, and throwing up. At the same time, Japanese mortar rounds were landing behind me, and as I sat there in the pouring rain and with mosquitoes biting me, I said to myself, “I wonder why they can’t get one of those rounds in here where it will do some good?” That was the low point.

But everyone was sick, everybody had malaria, and diarrhea was very common. It just amazed me, though, the endurance that the marines showed. As time went by, and as marines were evacuated because of disease or combat wounds, the word went out that unless you had a fever over 104, you weren’t allowed to go to sick bay. The corpsman would have to do what he could to medicate you, but you were not leaving.

So the longer we stayed, the more the men suffered. It wasn’t just sickness. We were ridden with jungle rot and skin infections. We had to be very careful with any kind of skin abrasion or cut because with the sweat and body oils, the mud and the dirt, and the dripping humidity, you had an excellent chance of getting an infection. I got fungus in my ears. I found that 100 percent pure alcohol would reduce the fungus, so one of the old chief pharmacist’s mates gave me a little bottle that would fit right in one of the ammo pouches on my belt.

We received a new drug called atabrine, and it was supposed to help prevent malaria. It had a strange side reaction, though. It turned the skin yellow, and the whites of the eyes would turn canary yellow. The scuttlebutt began that this was going to destroy male virility. I told my marines, “Look, there isn’t a woman within 2,000 miles of here….Take the damned pill!”

I had the section sergeants, the corpsman, platoon sergeant—and I did it myself—follow along to make sure each man took his atabrine. I am not sure how well it worked. Even though we had lots of losses to malaria, it probably would have been much worse without the atabrine. All I can say is at least enough of us survived to finish the campaign.

Foot problems were rampant. With the leather field shoes we had and the amount of humidity and mud and rain, our feet were rarely dry. I had my men take their shoes off and massage their feet, turn their socks wrong side out and put them on the other foot.

Food was always in short supply. We were truly on starvation rations. Everyone was losing weight. I dropped down to about 165 pounds from over 190. Many times we had nothing but a little captured Japanese rice, but it kept us alive. We had plenty of ammunition, though. We never lacked for 37mm rounds. Although it seemed we were always short of hand grenades. We had to conserve them. Also mortar ammunition was in short supply.

I saw it as one of my main jobs as a lieutenant to know my marines. One of them, I noticed, never shaved. He did not need to; he had no beard. This raised my suspicion. One day I asked him, “How old are you?”

“Oh, I’m 17, lieutenant.”

I said, “Dammit, I’m not going to do anything to you. Tell me the truth—how old are you?”

“I will be 15 my next birthday.”

I did not bother him about it. He was probably the best Browning automatic rifleman that I ever saw. He could play a tune with it. I said, “How did you get into the Marine Corps?”

He said, “I stole my brother’s birth certificate.”

So here he was, a 15-year-old boy, but really a good marine. He was not the only one—there were numerous underage marines—and I often wondered if those who came in under false names ever got their records straight.

While the sickness took many marines, we also had many killed and wounded. I didn’t think any of my marines ever suffered casualties from the Japanese naval shelling or their air attacks. Most of our casualties were from Japanese mortar rounds or rifle bullets—mostly rifle bullets, because I think they were having supply problems probably even worse than ours. One of my marines got hit by a sniper round; it hit right near the crotch, in his groin. The round had ripped a gaping hole in him. The flesh was torn back and bubbly yellow fat was evident. A main artery was severed, and every time his heart beat, blood spurted three or four feet in the air. He was mostly worried about his “plumbing” though. I told him, “It’s in good condition. You’ve just got a hell of a hole in your thigh.” I had the corpsman ride back with him to the aid station for fear that the tourniquet would slip off. We were using a rubber tube tourniquet, and when it got blood soaked it would slip. After that, I acquired a strap bandage tourniquet and carried that in my belt for the rest of the war.

Along the perimeter we maintained an aggressive defense, and that meant lots of patrolling. We would try to find out where the Japanese might be massing for another attack. They used the trails in the interior of the island to move from one area to the next. By checking these trails we could see signs of Japanese troop movement; there would be tracks or abandoned gear and equipment. These indicated troop movement and direction.

Although we were a 37mm gun crew, we were regarded as infantry, and we went on patrols. Of course, we left our 37mms in their positions and carried infantry weapons on these patrols. As a lieutenant I was expected to lead patrols.

Our patrols were various types, and you had an assigned mission for each patrol. I was never sent out to engage the enemy. You were sent out either to look at a specific area or to find a particular thing. Sometimes we would go out for just a few hours, other times longer.

The technique we used when we were going out was to find a spot where the Japanese had little, if anyone, present. We [would sneak] out in that area and go deep enough behind them to be able to move inland behind their lines. We never came back in through the route that we went out. I always made sure to get in touch with the commander of the unit where I would be reentering the lines. I didn’t want my patrol to get shot up by our own marines.

If we were going to be out overnight, we would pick a good defensive position and dig in, and as soon as it was real dark, we would move to our real position and set up there. I never spent the night at the place we were when the sun went down.

You had to be very quiet—no talking, no noise—and move very stealthily. On several patrols I actually saw Japanese. Sometimes we heard them, and sometimes we smelled them, or [both]. I was expected to observe the enemy but not be seen. There were occasions where patrols were ambushed. That never happened to me. I think maybe that was luck. Who knows?

It was just a matter of continual movement, continual hunger. People were ragged. I don’t think there was ever a time when the marines on Guadalcanal were adequately supplied. When the First Division landed, the navy pulled out with a lot of the supplies. It never got any better. [But] morale was pretty good. Oh, people bitched about food. When you became really hungry, food became ever-present in your mind. This was one of the few times when you would hear marines talking about food rather than women.

We had an attitude about the Japanese that began when we were briefed by the First Marine Division liaison officer, who had visited when we were on Samoa. We became convinced that the Japanese were a merciless foe, and we went there with the idea of killing them all. We maintained that attitude for the entire war. MHQ

[hr]

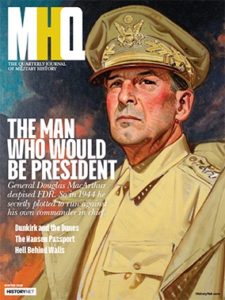

This article appears in the Winter 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: A Marine at Guadalcanal

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!