When escalating Civil War tensions reached Taos, New Mexico Territory, Confederate sympathizers tore down the Stars and Stripes from its staff on the town plaza and resisted all attempts to restore it. So Union supporters reportedly nailed the flag to a makeshift pole hewn from a young cottonwood tree, raised it over the plaza and guarded it round the clock. Among the zealous members of the color guard were renowned mountain man and scout Kit Carson and prominent fur trapper and Taos merchant Ceran St. Vrain. Such a purely symbolic act of no particular military significance marked something of a climax in the developing loyalties of Ceran St. Vrain, as he responded to the rapidly changing political landscape of the early 19th century and evolved from French expatriate to Mexican citizen to American patriot.

Ceran de Hault de Lassus de St. Vrain was born on May 5, 1802, in Spanish Lake, St. Louis County, in then French-controlled Louisiana Territory. He was descended from a family of French Flemish nobles who in the aftermath of the French Revolution found a more congenial environment in the New World. His father, former French naval officer Jacques Marcellin Ceran de Hault de Lassus de St. Vrain, immigrated to Louisiana in 1794 and soon moved north to St. Louis. In 1796 he married Marie Felicite Chauvet Dubreuil. Ceran, the fourth of their 10 children, grew up speaking primarily French. While the formal conclusion of the Louisiana Purchase in 1804 technically made the toddler Ceran and his siblings American citizens, given the influence of the surrounding community they likely grew up thinking of themselves as French.

After the family brewery burned down in 1813 and their 48-year-old father died insolvent five years later, the family fell on hard times, and Ceran went to live in the household of family friend and benefactor General Bernard Pratte, merchant, fur trader and War of 1812 veteran. Working as a clerk in Pratte’s St. Louis store, the teenager learned the fur trading business.

At the forefront of the North American fur trade of the early 19th century were such future legends as John Colter, Jedediah Smith, Jim Bridger and Kit Carson. Among the first Europeans to penetrate the American West, the mountain men were a tough and violent breed, better suited to a hard life on the untamed frontier than the comforts of civilized society. They made their living trapping fur-bearing animals, mostly beaver, and trading with frontier tribes, often taking Indian wives. Brought into trading centers like Santa Fe, the furs commanded high prices back East and in Europe.

Sited at the junction of the mighty Missouri and Mississippi, St. Louis was a natural hub for the Western fur trade, and its possibilities were not lost on the French community that grew up in the wake of the 17th-century explorations of Jacques Marquette, Louis Jolliet and Robert de La Salle. Merchants such as half-brothers Jean-Pierre and Auguste Chouteau, Jean-Pierre Cabanné, the Robidoux brothers and General Pratte were quick to see its advantages and developed thriving businesses. In the 1820s they turned their gaze southwest to the unexploited opportunities in New Mexico, newly liberated from Spanish rule in 1821.

In 1824, in partnership with Bernard Pratte and Co. and trader François Guérin, St. Vrain joined a caravan down the Santa Fe Trail to the Mexican-administered territory of New Mexico, stopping in the settlement of Taos near the namesake ancient tribal pueblo. For Ceran this initial trip to Taos was the beginning of a lifelong sojourn as a New Mexico merchant, as he pursued trapping and trading opportunities in the southern Rocky Mountains.

While still a young man St. Vrain earned his spurs as a mountain man in several trapping expeditions. In 1827 his mettle was sorely tested after joining a party of 36 trappers headed by General Pratte’s son Sylvestre, a close friend. When Sylvestre fell ill and died at the headwaters of the North Platte (present-day North Park in central Colorado), 25-year-old Ceran took the helm of the expedition, reportedly at the request of the party’s veteran trappers. On his watch an Indian shot trapper Tom Smith from ambush, striking him just below the knee. Smith’s lower leg required amputation, much of which the trapper himself performed with a butcher knife—till passing out from the pain. Defying the odds, he survived, thereafter calling himself “Peg-leg” Smith. After further hardships, Ceran successfully led the party back to Taos in May 1828.

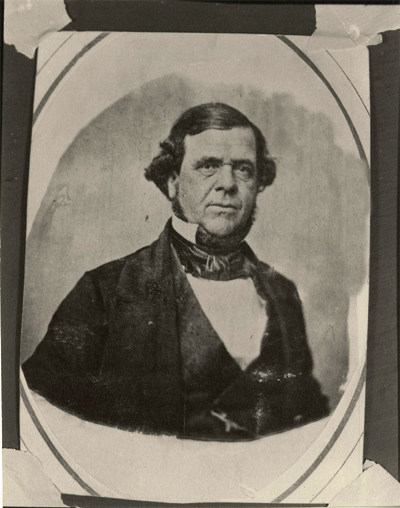

St. Vrain was a stout and powerfully built man with a round face, wide nose and dark bushy beard. The Indians called him “Black Beard.” He developed into a capable and successful trapper and merchant, branching out in a variety of allied enterprises, including supplies, land speculation and, later, flour mills and sawmills, liquor distillation, even newspaper publishing. He became active in civic affairs and was respected and well liked. In the ghostwritten words of longtime friend Kit Carson: “All the mountaineers considered him their best friend and treated him with the greatest respect. He now lives in New Mexico and commands the respect of all, American and Mexican alike.”

Lewis Garrard, young adventurer, traveling companion and sometime guest of St. Vrain had this to say about his host: “Mr. St. Vrain was a gentleman in the true sense of the term, his French descent imparting an exquisite, indefinable degree of politeness and, combined with the frankness of an ingenuous mountain man, made him an amiable fellow traveler. His kindness and respect toward me I shall always gratefully remember.”

St. Vrain may have been settling down in Taos, but he was nonetheless a prominent member of a foreign community viewed with increasing suspicion by Mexican authorities, native New Mexicans and Pueblo Indians

St. Vrain became a naturalized Mexican citizen on Feb. 15, 1831. It was in part a calculated decision, as citizenship made it easier to obtain a trapping license and facilitated such government largess as extensive land grants. By then he had put down roots in the Taos community, learning Spanish, adopting the Hispanicized name of Seràn Sambrano and taking a Mexican national as a wife. Over his lifetime St. Vrain had three wives—all local women—by whom he had a number of children. Admittedly, some or all of these unions may have been without the blessing of church or state, and their tenures may even have overlapped.

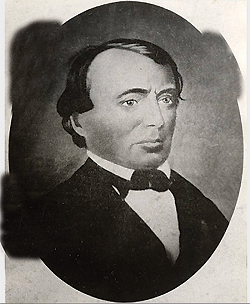

By early 1831 St. Vrain had partnered with friend and veteran fur trader Charles Bent to form Bent, St. Vrain and Co., which grew into a vast Southwestern trading empire with stores in Taos and Santa Fe. Family members, notably younger brothers William Bent and Marcellin St. Vrain, were also involved in the enterprise. Within a few years they built an adobe structure on the Arkansas River known as Bent’s Fort. Serving multiple functions—fort, trading post, residence, way station, supply depot and neutral site for negotiations with local Indian tribes—Bent’s Fort became a Santa Fe Trail landmark and cornerstone of the fur trade.

St. Vrain may have been settling down in Taos, but he was nonetheless a prominent member of a foreign community viewed with increasing suspicion by Mexican authorities, native New Mexicans and Pueblo Indians. Taos had become a center for mostly American expatriates, boasting a larger foreign population than even Santa Fe, and authorities suspected the Yanquis of harboring traitorous sympathies both during the Texas Revolution and amid rising tensions along the international border.

Indeed, when the United States declared war on Mexico in 1846, St. Vrain, like many fellow expatriates, came down on the side of the Americans. He and partner Charles Bent threw open the resources of Bent’s Fort to Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny and his 1,700 green troops, who took Santa Fe on August 15 without firing a shot. Three days later Kearny declared himself military governor of New Mexico and promptly appointed Bent its civilian governor.

Believing all was well in the territory, Kearny marched on to California, leaving a small force in Santa Fe under Colonel Sterling Price. But a rebellion was already brewing. Amid reports of discontent and resistance in Taos, Governor Bent returned home in January 1847 to soothe tensions and protect his family. Confident he would be well received, Bent refused a military escort. It was a fatal miscalculation. On January 19 discontented Mexican partisans, with help from Taos Pueblo Indians, launched an armed revolt, specifically targeting U.S. authorities. The Indians broke into Bent’s home, scalped the governor alive, murdered him and further mutilated his body, though his family was allowed to flee. The next day the rebels attacked a mill at nearby Arroyo Hondo and killed more Anglos, including several mountain men.

When news of the revolt reached Santa Fe, St. Vrain, at Colonel Price’s request, organized a volunteer company of 65 irregulars, many understandably vengeful mountain men among them. Despite the fur trader’s lack of military experience, Price then put him in charge of the company, with a field commission of captain. Numbering 353 men in all, the combined force of Price’s regulars and St. Vrain’s volunteers left for Taos on January 23, along the way defeating some 1,500 insurgents at La Cañada (Santa Cruz) and again at El Embudo (Velarde). While the rebels boasted a much larger force, they were poorly organized and lacked artillery. Price entered Taos unopposed on February 3.

The panicked rebels had taken refuge in Taos Pueblo, a solid wood and adobe stockade with a mission church to one corner. After an hours-long artillery bombardment, Price’s forces stormed the church, hacking at its walls with axes and setting fire to its roof before engaging in hand-to-hand combat with fleeing rebels. St. Vrain played a key role in the melee, by one account shooting and killing ringleader Pablo Chávez, by another narrowly averting impalement on a steel-pointed arrow in the hand of an Indian adversary. Casualties were extremely high among the defenders, who sued for peace the following day.

Military authorities imprisoned rebel leaders Tomás Romero and Pablo Montoya. Convicted of treason by a drumhead court-martial, Montoya was hanged on February 7. A disaffected soldier shot and killed Romero before he could be brought to trial. Fourteen other rebels faced charges of murder and treason before hastily organized civilian courts whose judges and juries were drawn largely from American sympathizers with tenuous claims to impartiality. St. Vrain served as interpreter. Unsurprisingly, all the accused were condemned to death and publicly hanged.

St. Vrain’s motives in rushing to the aid of the nascent U.S. government of New Mexico were likely twofold. Mountain man and trapper “Uncle Dick” Wootton, who helped put down the Taos Revolt, noted the primary reason:

The friendships of the mountain men were warm friendships. We had never seen the time when we were not ready to attempt the rescue of a friend whose life was in danger, and it was seldom indeed that the killing or wounding of one of our number had gone unavenged.

Among those who had been so brutally murdered at Taos and Arroyo Hondo were men who had been my warmest and best friends ever since I came to the country, and I felt that I should, if possible, do something toward securing punishment of their murderers and protecting the property which they had left for use of those who were entitled to it.

St. Vrain, who had led trapping expeditions and was an erstwhile mountain man himself, was almost certainly motivated by a similar fierce concern for family, friends and property, not to mention horror at the excesses of the insurrection. But there was probably a pragmatic reason as well. The Mexican government had been chronically unstable, largely ineffective in protecting and governing its northern territories, and stifling with regard to economic activity. American sovereignty promised better protection from hostile Indian tribes, a stronger political and legal structure, and far greater economic freedom. Such considerations were likely not lost on a shrewd and far-sighted entrepreneur. He went all in with the Americans.

St. Vrain’s military service did not end with the Mexican War. In 1855 he again assumed command of a volunteer company in cooperation with regular troops and Indian scouts—no longer enemies—from Taos Pueblo in a largely successful punitive operation against raiding Jicarilla Apaches and Muache Utes. He served as lieutenant colonel under Colonel Thomas Fauntleroy, with Kit Carson as chief of scouts.

During the Civil War years St. Vrain remained a staunch Unionist. At the outbreak of the war Colonel Edward R.S. Canby, newly appointed commander of the military Department of New Mexico, placed him at the head of the 1st New Mexico Volunteer Infantry, with Carson as his lieutenant colonel. Citing declining health, however, St. Vrain soon surrendered his command and focused instead on supplying the Union Army. With Carson at the fore, the 1st New Mexico Volunteers saw action at the Battle of Valverde in February 1862.

St. Vrain’s support for the war effort is not surprising. With exceptions, New Mexicans tended to favor the Union

St. Vrain’s support for the war effort is not surprising. With exceptions, New Mexicans tended to favor the Union. Northern residents had especially strong ties via trade with Missouri. They were accustomed to exchanging Yankee dollars in commercial transactions and distrusted the newly minted Confederate currency. Texas bore blame for some of the ill will farther south. During its years as an independent republic, it had laid claim to New Mexican territory, which it sought to annex with ill-fated military expeditions. Residual resentment over those incursions extended to the Confederacy, of which Texas was a part. Having lived in New Mexico for nearly four decades, St. Vrain likely shared such sentiments. Moreover the savvy businessman probably anticipated lucrative Civil War contracts from the well-equipped Union Army.

But as the Taos Plaza flag incident attests, more than self-interest motivated St. Vrain. The United States was in the throes of a major revolution in outlook that paralleled the turmoil on the Civil War battlefields. From a federation of quarreling states, it was becoming a nation in thought and deed as well as name. It would be strange indeed if a man with the soul and vision of St. Vrain were unaffected by this transformation. He lived long enough to witness its rebirth.

Ceran St. Vrain died at age 68 on Oct. 28, 1870, and was buried in a small family cemetery near his home in Mora, New Mexico Territory. Some 2,000 mourners attended his funeral. Even today the Stars and Strips flies round the clock in Taos Plaza in commemoration of the flag-raising at the outbreak of the Civil War.

The economic, political and military upheavals in North America in the first half of the 19th century imposed complex and often contradictory pressure to personal notions of country, citizenship and loyalty. In the life of Ceran St. Vrain we see how a capable and respected individual navigated these waters from expatriate Frenchman and de facto American through Mexican citizen, American sympathizer and, finally, Union partisan and American patriot. WW

Daniel R. Seligman, who writes from Needham, Mass. is a retired engineer with a lifelong interest in the American West. Recommended for further reading: Bent’s Fort, by David Lavender; The Taos Trappers: The Fur Trade in the Far Southwest, 1540–1846, by David J. Weber; Ceran St. Vrain: American Frontier Entrepreneur, by Ronald K. Wetherington; and Blood and Thunder: An Epic of the American West, by Hampton Sides.