At the Café Copoule in Paris in the spring of 1916, three American soldiers of the French Foreign Legion were commiserating with a fourth who was convalescing from a shrapnel wound. Jeff Dickson, a white Mississippian, asked Eugene Bullard, his injured black comrade in arms from Georgia, “Gene, suppose they find you’re too lame for the infantry?” Bullard’s answer raised eyebrows around the table: “I’ll go into the Air Service.”

“Air Force?” Dickson exclaimed.“You know damn well, Gene, there aren’t any Negroes in aviation.” “Sure do,” Bullard said.“That’s why I want to get into it. There must be a first to everything, and I’m going to be the first Negro military pilot.” That friendly argument swiftly evolved into a $2,000 wager. Bullard, who would emerge as history’s first certified black American aviator, won the bet.

While a black pilot was unprecedented in 1916, accepting challenges and overcoming obstacles was nothing new for Eugene Jacques Bullard. Born on October 9, 1894, he was the youngest son among 10 children, three of whom died in childbirth. His father, Octave Bullard, was the son of a black slave. His Creek Indian mother, Joyakee, died when he was 6. Living in Columbus, Ga., young Gene grew up dealing with Southern bigotry, but he was inspired by tales his father told him of a faraway land where a man’s social prospects were not limited by his skin color: France.

In 1904, determined to reach France and begin a new life, 10-year-old Gene began a rambling odyssey that led to his stowing away aboard a merchant freighter—only to be caught and put ashore in Aberdeen, Scotland. After taking a variety of jobs, he became a bantamweight boxer in Liverpool at age 16 and by age 17 had become a lightweight champion.

With 42 professional bouts behind him, Bullard finally achieved his childhood dream on November 28, 1913, when he arrived in Paris. On August 3, 1914, Germany declared war on France, and the next day its armies invaded France and neutral Belgium. Bullard, though still an American citizen, decided that he wanted to defend the country in which he had sought equality. He joined the Foreign Legion on October 19.

As a soldier in the Legion’s 3rd Régiment de Marche and later the 170th Régiment de Ligne, Bullard fought in the Champagne and Verdun campaigns with such distinction that he was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Star as well as the Médaille Militaire. He was wounded three times, the last—on March 5, 1916—leaving him too disabled for further infantry service. It was then that Bullard thought of rejoining the fight as an aviator, his ambition stoked by that friendly wager at the Café Copoule.

With the help of some influential friends, Bullard was accepted into the French Aéronautique Militaire as a machine-gunner. He started training at Cazaux on October 6, but while there he met a fellow Legionnaire, Edmond Charles Clinton Genet, who had already qualified as a pilot and was on hand for gunnery training.

Genet told Bullard about the Lafayette Flying Corps, an organization for farming American volunteers out to French squadrons, and explained that Helen Vanderbilt had established a fund from which its pilots could draw 50 francs (then about $30) a month (at that point Bullard’s Legion pay was a miserly 30 cents per month). With Genet’s backing, Bullard joined the LFC on November 15, requested pilot training and 15 days later reported to the aviation school at Tours.

Bullard called the elderly aircraft he flew at Tours cages á poules (chicken coops). His training began with mastering the ground handling characteristics of a Blériot XI with clipped wings, officially called a rouleur but more popularly known as a pingouin. After three days of that, Bullard flew a progressive series of hops and flights in a Blériot and a Caudron G.3. Following a serpentine maneuver and a spiral from 2,000 feet with the engine shut off—the trick being to land at a predetermined spot—Bullard received his pilot’s certificate or brevet, No. 6259, on July 20, 1917.

Granted six weeks’ leave, Bullard met his three friends in Paris, wearing his blue aviator’s tunic with wings on the collar. Jeff Dickson remarked, “Bullard, I am sorry I lost that kind of money to you or anyone else, but I am glad that the first military Negro pilot aviator came from Dixie.”

Bullard resumed advanced training at Châteauroux, in Caudron G.3s and G.4s. By his own admission, he was never a great pilot and had some difficulty mastering the twin-engine G.4.

From Châteauroux he was ordered to Avord, where he was placed in charge of the sleeping quarters of other American volunteer airmen. Weeks passed, and Bullard could not understand why pilots who arrived after him were going to the front while he was still stuck on ground duty.

Meanwhile the United States had joined the Allied cause on April 6, 1917. Ten days later Bullard’s friend Edmond Genet, flying in the all-American volunteer Escadrille N.124 “Lafayette,” was shot down by anti-aircraft fire—the first American to die since his country officially entered the war.

Hoping to obtain an officer’s commission in the budding U.S. Army Air Service, Bullard went to Paris for his medical examination. The doctors claimed that although he had flat feet and large tonsils, he was otherwise fit to fly, but he didn’t hear anything more about a transfer for some time.

Bullard fretted until August 20, when he received orders to report to Plessis Belleville, the last stop before a unit assignment. Returning from a practice flight on his first day there, he found new orders awaiting him, to report to Escadrille N.93 at Bar-le-Duc, 40 miles behind the lines near Verdun, where he had fought as a Legionnaire. Upon receiving the news, Bullard remarked, “I’m heading for heaven, hell or glory.”

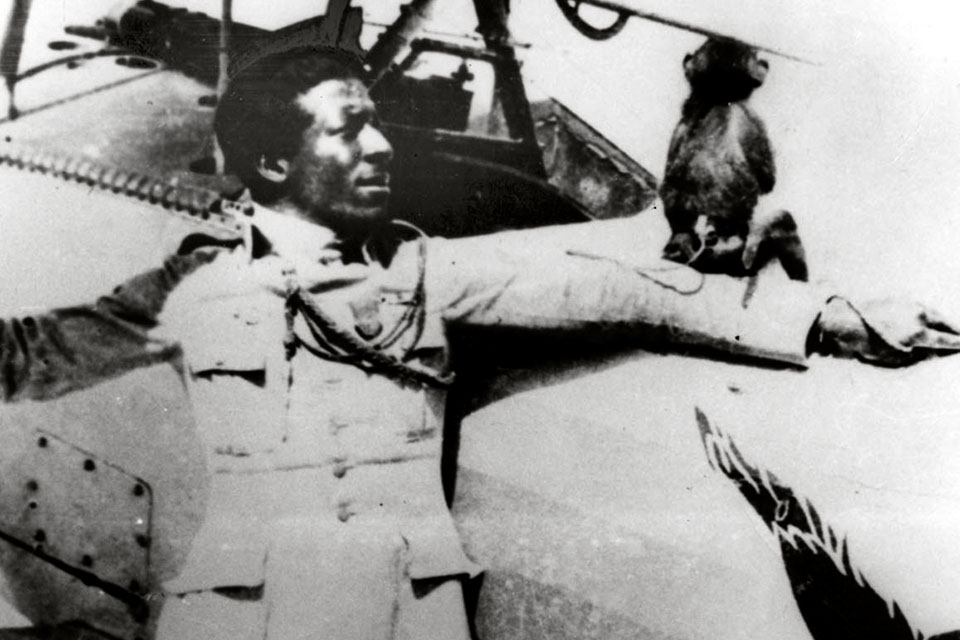

During his leave, Bullard had bought a rhesus monkey. When he arrived at N.93 on August 27, he and his simian companion, Jimmy, quickly became the subject of much friendly banter with their French squadron mates. After a week of familiarization flying Bullard was asked by Commandant Jean Menard, leader of Groupe de Combat 15 (GC.15), of which N.93 was part, if he was ready to fight. The American flier was so enthusiastic that Menard felt it necessary to remind him of the cardinal rules for a neophyte pilot: Do not be too hasty, do not leave formation and above all do not attack—and always be prepared to defend yourself in a split second.

As a general rule, the French scheduled flying time for two hours in the air and four hours on the ground unless there was an emergency. On September 8, Bullard was scheduled for two mixed group patrols, both led by Captain Armand Pinsard of N.78. In the course of addressing his pilots in person, Menard asked them to wish Bullard well on his first mission over enemy territory, remarking that he had more medals than any of them but fewer flying hours than all of them. Amid a roar of laughter, he added that it was their duty to try to prevent Jimmy from becoming an orphan.

As Bullard settled into the cockpit, Jimmy snuggled into the lower half of his flying suit. Taking off and climbing to 6,000 feet, the patrol formed a V formation with Pinsard at the apex. Bullard, his head filled with all the “dos” and “don’ts” of aerial combat, worked hard to maintain formation while watching his leader’s every signal and scanning in all directions, but the morning patrol turned out to be uneventful.

The afternoon patrol turned out quite differently. The French were forming up at 6,000 feet when they spotted four German bombers being escorted by 16 fighters. Air battles rarely lasted more than one or two minutes at that point in the war. They were often over before inexperienced fliers even got their bearings. Bullard later confessed to firing at anything that appeared in front of him in a fight that transpired so quickly he had no time to feel frightened.

The French claimed four bombers and two of their escorts. Only upon returning to base did Bullard realize that two of his comrades were missing. He had fired 75 rounds from his machine gun, and his mechanic found seven bullets in the plane’s tail.

Over the next two weeks Bullard gained experience and got over his jitters. On September 13, he was transferred to Spa.85, a neighboring squadron. There, he decorated his Spad VII with a bleeding red heart with a dagger through it on the fuselage side, along with the slogan “Tout sang que coule est rouge” (“All blood runs red”).

Combat was almost a daily occurrence over Verdun at that juncture. During a dogfight on November 7, Bullard finally drove an opponent down, only to be attacked in turn and crash-land in French lines with 96 bullet holes in his plane. Strict French confirmation standards required additional witnesses on the ground or from a balloon, which meant that Bullard’s victim, which fell deep inside German territory, was counted only as a probable.

A few days later Bullard became separated from his formation and then spotted seven Pfalz D.IIIs 3,000 feet below him. Banking into a cloud, he came up behind the formation, squinted into the sun one last time to check for an ambush and then dived. As his machine gun blazed, the rearmost plane in the flight staggered, stalled and fell away in a straight dive. Once again, however, a lack of witnesses prevented Bullard’s second claim from being confirmed.

While returning from a brief leave in Paris, Bullard got into an altercation with a French officer. The American flier managed to avoid a court-martial only because of his superb combat record.

On November 11, however, he was dismissed from the Aéronautique Militaire, returned to his old regiment, the 170th, and then was further humiliated by being assigned to its service battalion until his honorable discharge on October 23, 1919. Jimmy stayed behind as N.93’s mascot, but he did not survive the war—he became a victim of the influenza epidemic of 1918. Although Bullard’s flying career had come to a premature conclusion, his devotion to the Legion and his beloved France never waned.

In the 1920s and 1930s Bullard worked as a jazz drummer and also ran an athletic club and some nightclubs in Europe. During World War II he enlisted in a machine gun company of the 51st Infantry Regiment, and was wounded while fighting at Orléans on June 18, 1940.

Escaping from German-occupied France, he arrived in New York on July 15, where he was later joined by his two daughters. Back in the United States for the first time in 34 years, Bullard settled in Harlem and spent the rest of the war working as a stevedore at the Staten Island shipyard.

Eugene Bullard was employed as an elevator operator at Rockefeller Center in 1954 when French President Charles de Gaulle invited him back to Paris, where he helped to relight the flame on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier under the Arc de Triomphe. On October 9, 1959, the American pilot was again contacted by the French consulate, this time to notify him that he was about to be made a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur for his service in two world wars.

On October 12, 1961, three days after his 67th birthday, Bullard died of stomach cancer. The world’s first black aviator was laid to rest in the Federation of French War Veterans cemetery in Flushing, N.Y. Per his request, he was wearing the uniform of a French Foreign Legionnaire, and his casket was draped in the French tricolor.

Thirty-three years later, President Bill Clinton promoted Bullard to the rank of second lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force.

Originally published in the March 2007 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.