Joseph Bailey built bulwarks to trap water, then let loose the rising flood and saved the Union fleet

[divider]It doesn’t take a mathematical genius to determine that boats with 7-foot drafts sitting in three feet of water aren’t going anywhere. Yet that was the dilemma Union Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter faced as he attempted to navigate his Mississippi Squadron down the Red River in late April 1864. The entire Red River Campaign, in fact, may well have ended abruptly at a low-water spot off Alexandria, La., were it not for the practical genius and engineering skill of a Union officer from the backwoods of Wisconsin.

[divider_flat]THE RED RIVER CAMPAIGN was an ill-conceived Federal Army–Navy offensive in the spring of 1864, which soon became known, according to one chronicler, as “one of the biggest military fiascos of the Civil War,” and by Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman himself as “one damn blunder from beginning to end.” The mission ostensibly was for the combined Union force to proceed up the unpredictable Red River through Louisiana, seize the strategically vital city of Shreveport—home of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department’s headquarters—and then establish a presence in eastern Texas while commandeering as much Southern cotton as possible.

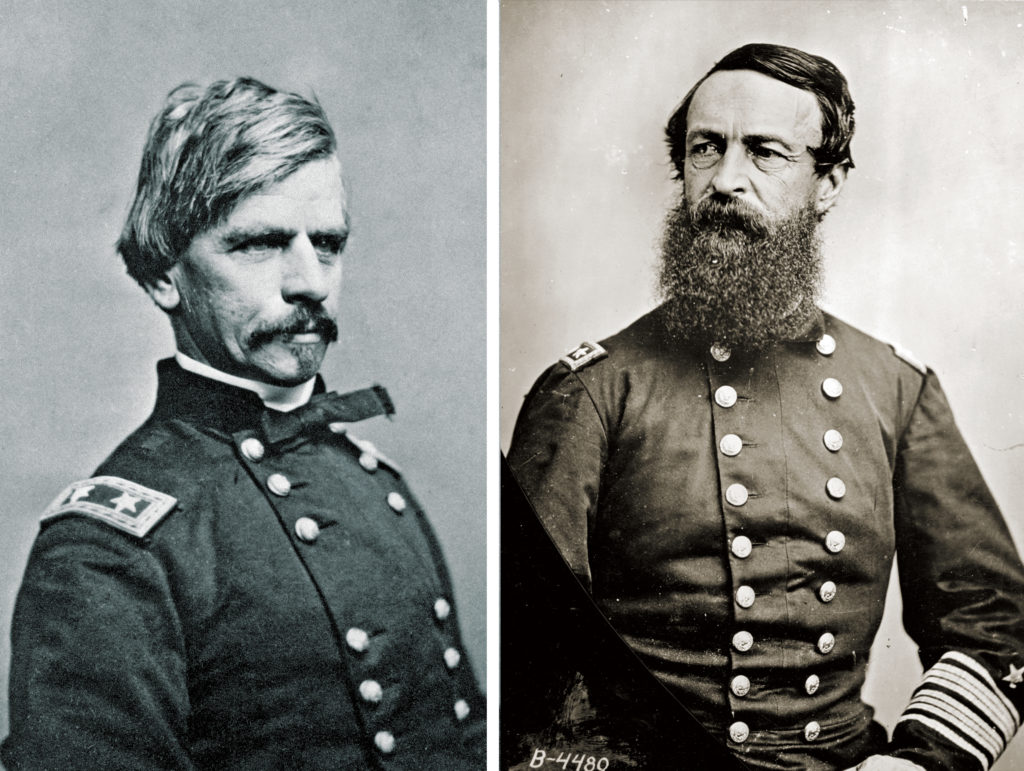

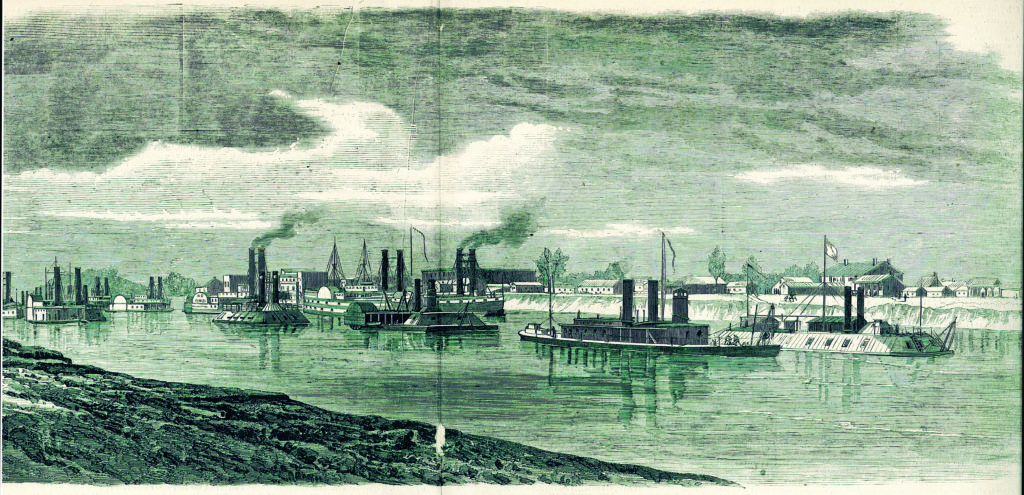

Under the joint command of Admiral Porter (who had earlier expressed grave doubt as to the campaign’s viability) and the inept, hard-luck political general Nathaniel P. Banks, the operation was the largest land-and-water expedition of the war. Banks’ force of more than 30,000 men was to act in concert with a 33-vessel flotilla consisting of troop transports, supply boats, ironclads, timberclads, tinclads, high-speed rams, river monitors, and support vessels—and boasted an impressive 210 heavy guns.

From the beginning, however, Banks’ men performed poorly. Because the roads they traversed did not necessarily follow the banks of the river, they advanced at a much slower rate of speed than Porter’s fleet and generally remained out of range of reliable support from the Federal naval guns. After fighting one losing engagement—the April 8 Battle of Mansfield, La.—to a numerically inferior enemy and narrowly surviving a second, the Battle of Pleasant Hill, the following day, Banks abandoned any thought of capturing Shreveport and ordered his dispirited men to retreat downriver.

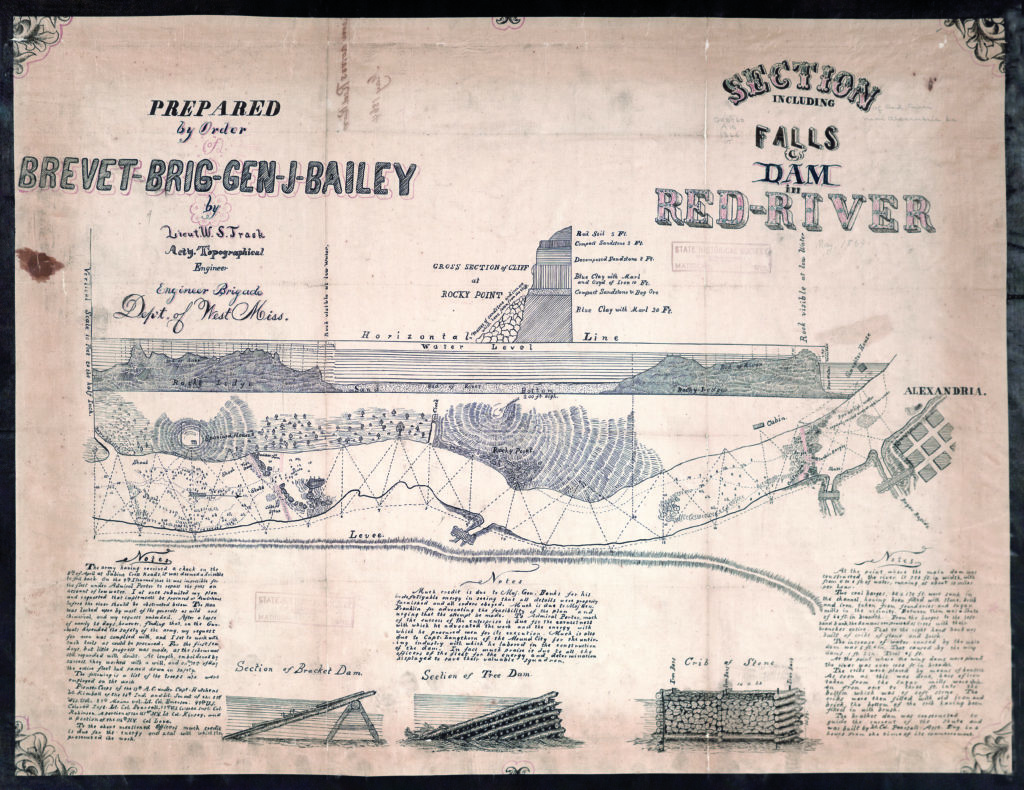

Porter’s gunboats and their support vessels reversed course as well and steamed back down the river, under incessant enemy fire. After five days, they came upon a mile-long, 758-foot-wide stretch of water at Alexandria, about midway between Shreveport and Baton Rouge, that featured two 6-foot-high waterfalls bookending three sets of rapids. The crews of Porter’s flotilla began to offload their heavy cargoes in preparation for running this daunting obstacle course. Unfortunately, within a short time, the water level dropped from nine feet to just more than three feet, virtually grounding the fleet’s 10 heaviest gunboats on the river bottom. Porter, with considerable distance between his vessels and the Mississippi River, was unable to move and faced the possibility of scuttling his entire fleet.

To make matters worse, Confederate artillery and snipers kept up constant fire on the vessels and their crews from the north side of the river near Pineville. Fortunately for the Federals, Banks had left a significantly sized force on the river’s south side at Alexandria during his retreat. Those troops were about all that stood in the way of total disaster.

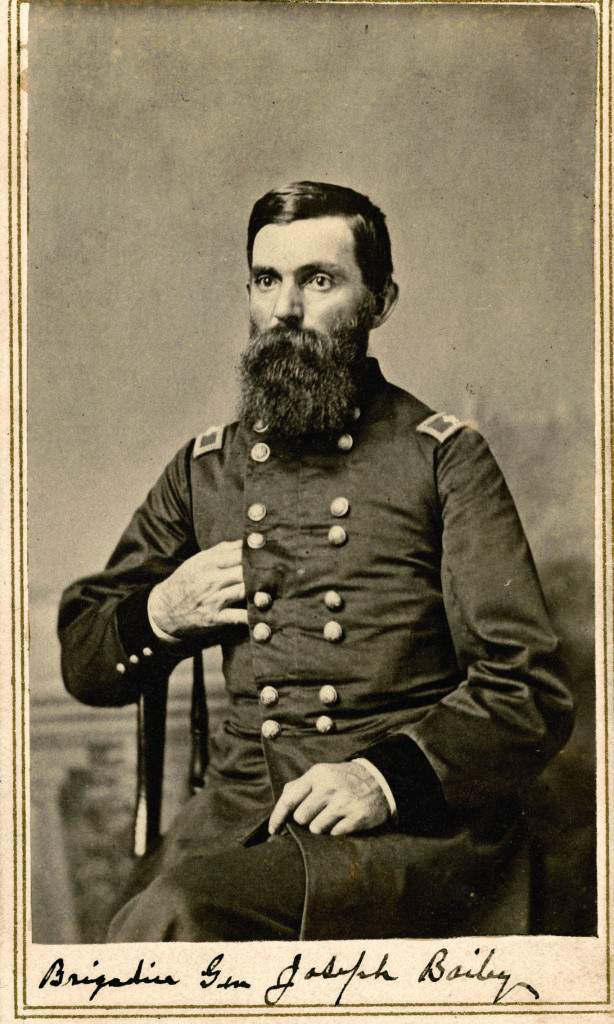

Porter and Banks faced potentially career-ending dilemmas. But just as things seemed utterly hopeless, an officer in the 19th Corps offered Porter a possible solution: Lt. Col. Joseph Bailey, a civil engineer in civilian life, suggested that they build dams to raise the water level. If anyone in the Union Army was familiar with the building of dams, it was Bailey. Before the war, he had been a Wisconsin lumberman, and had built his share of dams to facilitate the running of logs to the sawmills. And after the Union capture of Port Hudson, La., in July 1863, he had constructed a dam to float two abandoned Confederate vessels that were stuck in the mud.

Bailey actually had proposed the dam option in early April, while accompanying the army’s main body north, concerned that the falls at this point of the Red River would be a significant problem for the fleet’s heavier boats if the water level were too low. A few of those hefty boats, in fact, had been pulled across the falls heading upriver when that had occurred.

Porter, however, was not impressed, later recalling that his top engineers mocked the plan. “The proposition,” he would write, “looked like madness.”

Now, given the increasingly dire situation and aware the river was threatening to drop even more, Porter reluctantly gave his approval. In a message to Bailey’s commander, Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin, he wrote, “Tell General Franklin that if [Bailey] will build a dam or anything else, and get me out of this scrape, I’ll be eternally grateful to him.”

Porter immediately diverted sailors, flatboats, and barges to the project. He further enlisted Banks’ aid in reassigning some 3,000 troops, as well as scores of mules, oxen, and wagons.

Below the falls, Bailey constructed both a crib dam (filled with bricks, stones, and railroad iron) and a tree dam. Bailey then had four 24- by 170-foot coal barges, filled with anything that would sink, submerged at intervals in the middle of the resulting 150-foot-wide gap. This portion of the dam was designed to completely block the water’s flow. Farther upstream, he built two wing dams on both sides of the river to help funnel the water to the main dam area. It was his plan, once the water level rose to a sufficient height, to blast or break through the barriers, thereby allowing the Union vessels to ride the rushing torrent over and past the falls and rapids.

Trees were plentiful on the north bank near Pineville, and Bailey ordered the cutting and trimming of oaks, elms, and pines. The operation was blessed with soldiers from Wisconsin, Maine, and New York who were already familiar with the use of axes and the felling of timber. It also helped greatly that the 97th and 99th U.S. Colored Troops, two engineer regiments, were on hand to perform the majority of the main dam’s construction.

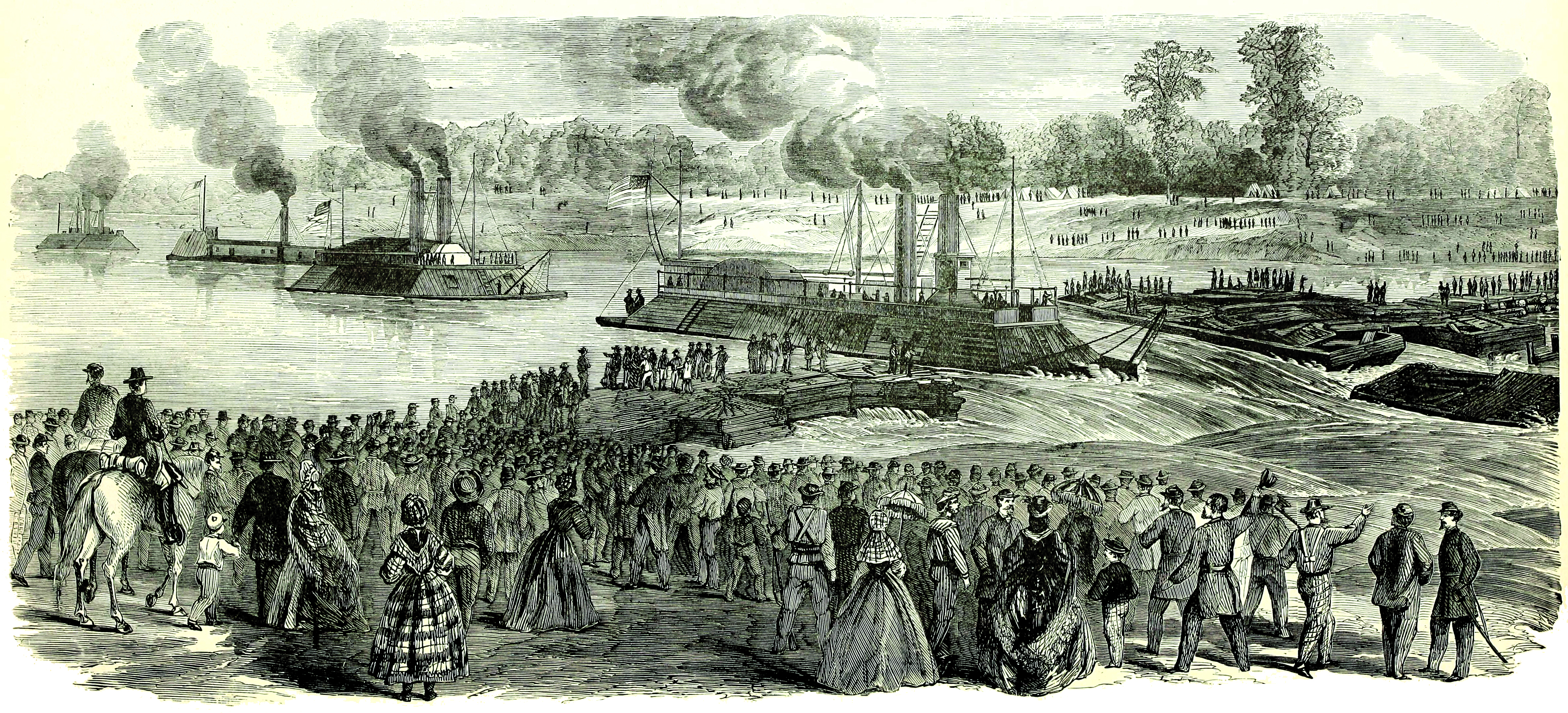

Thousands of spectators—Union officers, soldiers, and sailors as well as citizens of Alexandria and Pineville—observed the work from both banks, most of them convinced the plan was pure folly. Bemused Rebels watched from their positions, punctuating their sniping with mocking shouts of “How’s your big dam progressing?” Porter himself later wrote of the men working on the dams, “[N]ot one in fifty believed in the success of the undertaking.”

Gradually the water began to rise. By May 8, it had gone up more than five feet. Then, early on the morning of the 9th, a thunderous roar was heard, as the tremendous built-up water pressure upon the structures broke two barges free of the dam. Bailey had always envisioned them breaking through at some point, but this was both an unforeseen accident and—if quickly capitalized upon—a great opportunity.

Porter immediately seized the moment and ordered the timberclad gunboat Lexington to run the gap between the two dams. As one Union observer wrote in his diary, “The Lexington succeeded in getting over the falls and then steered directly for the opening in the dam, through which the water was dashing so furiously that it seemed as if certain destruction would be her fate. Ten thousand spectators breathlessly awaited the result. She entered the gap with a full head of steam; passed down the roaring, rushing torrent; made several spasmodic rolls; hung for a moment, with a harsh, grating sound, on the rocks below; was then swept into deep water and rounded to by the bank of the river. Such a cheer arose from that vast multitude of sailors and soldiers, when the noble vessel was seen in safety below the falls, as we had never heard before, and certainly have not heard since.”

Three more gunboats successfully tailed Lexington. The other larger vessels, however, were slow to follow, their engines not yet running and steamed up. According to the State of Louisiana historical website:

“Had the rest of the fleet been prepared, all of the boats might have escaped at that time. However, the navy’s lack of confidence in the dam had given way to apathy, and as the released water rushed through the break, valuable time was wasted as the fleet gathered steam to attempt the run. Eventually, the water behind the dam fell and six gunboats still remained trapped.”

By now, it seemed, everyone had faith in Bailey’s plan, and work immediately began to repair the dam. Bailey used the same methods involving cribs and felled trees, but this time he built a series of smaller dams near the upper set of rapids. This achieved the dual purpose of easing the pressure on the original dam while creating a channel for the remaining vessels. To the strains of a military band playing “Battle Hymn of the Republic” and the “Star Spangled Banner,” and with the banks again reverberating with the cheers of thousands, the remaining six gunboats made their way safely over the falls and past the last set of rapids.

With little delay, Porter continued steaming his tattered fleet down-river toward the welcome waters of the Mississippi. Meanwhile, Confederate Maj. Gen. Richard Taylor, whose smaller force had already defeated Banks at Mansfield, continued to pursue and harass the Yankees, burning bridges, blocking roads, and shooting at Porter’s vessels as they attempted to resupply Banks’ beleaguered men.

When Banks’ army reached the Atchafalaya River, it found itself trapped on the wide river’s bank, necessitating Bailey’s services and ingenuity to be called upon again. He designed and built a bridge across the water, consisting of some two dozen transport vessels. As Orton S. Clark of the 116th New York Infantry later wrote: “They were all river steamers, and getting alongside each other, with their stems up stream, they formed a bridge which answered the purpose nicely. All our large wagon train and artillery had to be run over by hand. Hour after hour we worked until at last every army wagon, gun, caisson, forge, mule, horse and man were across the stream, and in a very short time the bridge had dissolved into distinct bodies, which ascending the Atchafalaya, were soon at the mouth of the Red River.”

The entire Red River enterprise had been, as Sherman stated, a series of disasters from start to finish, with not one objective fully attained. Some historians have suggested that campaign blunders actually prolonged the war by several months. Ultimately, the campaign cost the lives of more than 5,500 soldiers and sailors, as well as the destruction of a number of vessels, including an ironclad, two tinclads, and four transports. And though Porter would make a considerable amount of money from the sale of the cotton he had confiscated as a prize of war, Banks’ military career was virtually over.

There would be one bright note: The officers and men of the joint operation emerged from the dismal experience with a bona fide hero. After the campaign ended, Bailey and his dam were the subjects of Union-wide newspaper articles, in which he was touted as the “Hero of the Red River.”

Meanwhile, President Abraham Lincoln confirmed Bailey’s promotion to brevet brigadier general, and Congress voted him a gold medal and the official thanks of Congress. On behalf of the Navy, Porter gave him what was described at the time as “an elegant and costly sword, with a rich scabbard and belt, from the celebrated firm of Tiffany & Co., New York.” The dedication on the scabbard is engraved:

Presented to Brevet Brigadier General Joseph Bailey, U.S. Volunteers, by Rear Admiral David D. Porter, commanding Mississippi Squadron, as a mark of respect for his indomitable perseverance, energy and skill, in constructing a dam across Red River, enabling the gunboats under his command to float out in safety.

A group of naval officers presented Bailey with a punch bowl, also from Tiffany. A scene is etched on one side of the bowl, depicting several Union gunboats above Bailey’s Dam. According to tradition, in order to afford such a lavish gift, each of Bailey’s fellow officers requested a part of his pay in silver coins, which were then sent to Tiffany to be melted down for the making of the bowl.

Joseph Bailey left the service in 1865, having served in the Union Army for the full four years of the war. Not only had he enlisted immediately following Lincoln’s first call for volunteers in 1861, he recruited 100 local men as well, whom he formed—as their elected captain—into a company called the Columbia County Rifles. Bailey and his company were mustered into the U.S. Army as Company D of the 4th Wisconsin Infantry and subsequently saw considerable action while serving in the Trans-Mississippi.

Tragically, after serving throughout the entire war without personal mishap, Bailey outlived the end of hostilities by less than two years. A year after returning to his home in Kilbourn City (now Wisconsin Dells), he moved with his wife and four children to Vernon County in western Missouri, where he was elected county sheriff. In late March of the following year, he set out to arrest two brothers (both of whom had reputedly served with Quantrill’s guerrillas during the war) on a charge of hog-stealing. For reasons that have never been satisfactorily explained, Bailey did not disarm his prisoners, and as he escorted them to the jail in Nevada, Mo., the brothers shot and killed him, and made their escape.

Despite the posting of rewards in excess of $3,000—a huge sum at the time, equal to more than $50,000 today—the two were never captured. Joseph Bailey deserved better; it was a tragic end for the man who had led the gallant effort to save the Union Navy’s premier brown-water squadron from capture or destruction.

In 1895, the Wisconsin legislature voted to purchase the dress sword and presentation punch bowl and place them in the collection of the Wisconsin Historical Society. Seventeen years later, artist Hugo Ballin painted a mural on the wall of the new Wisconsin State Capitol’s Executive Chambers. It depicts a uniformed Joseph Bailey, being crowned with the laurel wreath of victory.

Ron Soodalter writes from Cold Spring, N.Y. America’s Civil War thanks Richard H. Holloway, interpretive ranger at Forts Randolph and Buhlow State Historic Site in Louisiana, for his contributions to this story.