The crowd of 10,000 that had assembled at Bay Farm Island across the bay from San Francisco watched intently on July 14, 1927, as a Travel Air 5000 high-winged monoplane dubbed City of Oakland warmed up on the runway at Oakland Airport, preparing for a transpacific flight attempt. Most of these spectators were aware that the flight pilots and their sponsors had already faced major problems getting City of Oakland into the air. As a result, there was a mood of skepticism about the upcoming flight.

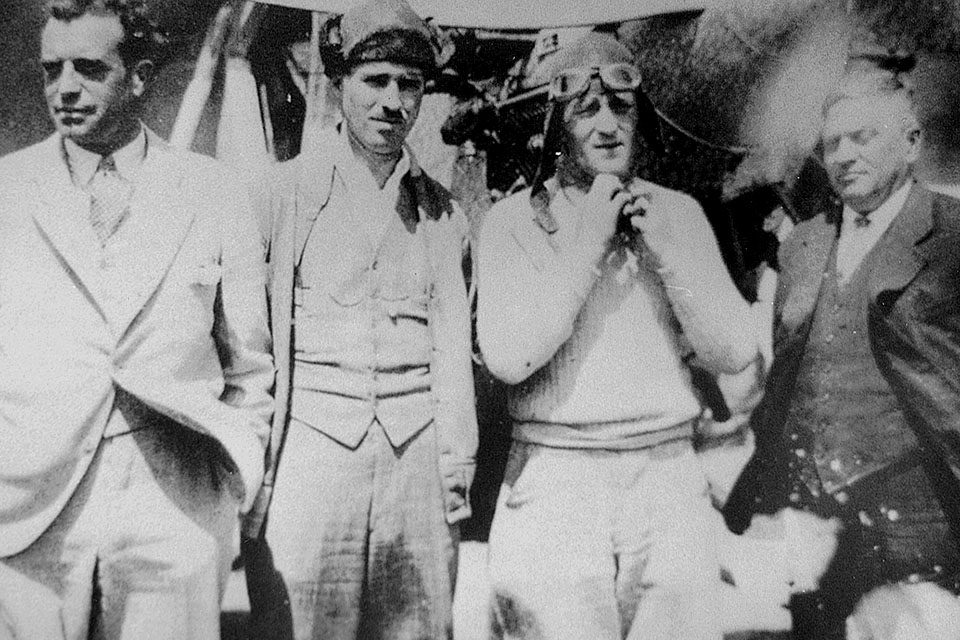

Built in Wichita, Kan., the Travel Air was about to take off on its second attempt to fly to Honolulu. Its experienced pilot was 34-year-old Ernest L. Smith. His navigator was 29-year-old Emory Bronte, a merchant marine captain.

Smith, born in Reno, Nev., had moved with his family to San Francisco in time to experience the great earthquake of 1906. Later the Smiths moved to Oakland, where ‘Ernie’ graduated from high school and spent two years at the University of California at Berkeley. He then went on to dental training, which was interrupted by the U.S. entry into World War I. After serving briefly in the medical corps, Smith transferred to the new U.S. Army Air Service and learned to fly at Rockwell Field in San Diego. He spent the rest of the war as an instructor at March Field in Riverside, then joined the Army’s aviation reserve while flying for the Forest Service in the Pacific Northwest. In 1926 he worked for Pacific Air Transport as a pilot.

Bronte, a native of New York, had gone to sea at age 15 before entering the Navy in World War I. After the war he joined Isthmian Steamship Company, working his way up from third mate to master. In 1923 he relocated to San Francisco to work for McCormick Steamship Company, after which he became the Pacific Coast representative of the Inland Waterways Corporation. Along the way he had authored a book on navigation, but government service had also whetted his interest in the law, a field he planned to study after the 1927 flight was over. He had taken flying lessons and had soloed in a Curtiss JN-4 ‘Jenny’ but had no actual pilot’s license.

As the departure date neared in July 1927, each man had private concerns about the 26-hour flight they were preparing to undertake. Smith was elated about the trip ahead, but he was also apprehensive about the ability of the plane to fly 2,100 miles nonstop, since this Travel Air model had never faced such a challenge. He was also concerned about the negative publicity City of Oakland‘s crew had already received. In the past two weeks, his sponsors had allowed their internal disagreements to be reported in the press, giving rise to speculation that the entire enterprise was disorganized and in danger of failing before he even got the plane into the air.

Bronte, too, was excited at the opportunity to serve as navigator on a pioneering transoceanic flight, but he was also a bit uneasy about why hispredecessor, merchant mariner Charles R. Carter, had bowed out after the initial flight attempt on June 28. On that date the plane had been forced to turn back only a few minutes into the air. Carter’s decision not to go along on a second flight had given Bronte his chance for fame, but it had also created doubts about his and Smith’s chances of making it to the islands.

On June 28, 1927, City of Oakland had taken off along with the Fokker Trimotor Bird of Paradise, flown by U.S. Army Air Corps pilots. The two planes had been engaged in an informal head-to-head race to Honolulu. Unlike some other high-profile flights of 1927, this one offered no prize money. The winner would simply have the honor of being the first to have flown to Hawaii from the West Coast. A subtle distinction had to be made about the goal in the record books, since a 1925 effort by the U.S. Navy to fly to Honolulu had ended with the plane, a Naval Aircraft Factory PN-9 flying boat, running out of gas before it reached Hawaii’s shores. The crew had sailed and drifted the last 450 miles to the island of Kauai over a nine-day period.

The civilian fliers in the June 1927 flight had been the sentimental favorites with the general public in the weeks leading up to the contest, but the Army crewmen had experienced far less trouble with their flight preparations than had Smith and Carter. Local political and aviation officials had campaigned actively to prevent City of Oakland from making the flight. In contrast to many of the specially built planes then being used in transoceanic attempts — such as Charles A. Lindbergh’s Ryan NYP Spirit of St. Louis — the Travel Air had been in commercial service for two months for Pacific Air Transport, flying between Los Angeles and San Francisco. One pundit declared that flying the Pacific in such a used plane would be suicidal. From the standpoint of safety, however, the distinction was immaterial; the first plane ever to cross the Atlantic nonstop, a Vickers Vimy bomber, had entered service at the end of World War I before it went on to make history in 1919.

City of Oakland had been purchased from the airline by a group of sponsors headed by Anthony Parente, a rags-to-riches businessman from the North Beach district of San Francisco. Contracts were drawn up between these backers and the fliers — who also owned a share of the plane — providing for the distribution of any money earned with the plane, an indication that they anticipated a successful future for the aircraft. The project team had sometimes been indiscreet, however, allowing reporters to get wind of their arrangements and disagreements about various features of the contracts.The Travel Air had been re-engined and extensively rebuilt in San Francisco. During that time, the commandant of Crissy Field, the Army’s air base at San Francisco’s Presidio, had denied the use of the field to the civilian plane, insisting that only military aircraft could utilize the facility. In spite of this setback, the Army personnel had remained generally cooperative and helpful toward all those associated with City of Oakland.

Other difficulties surfaced as the takeoff date approached. Several critics claimed it was unsportsmanlike of the group sponsoring the Travel Air to attempt a flight to Hawaii prior to August 12, 1927, which had been announced as the beginning of the eligibility period for the Dole race to Honolulu, an upcoming competition sponsored by well-known pineapple magnate James D. Dole. The Army fliers were spared this type of criticism because the Dole race was limited to civilian aircraft only.

With Lindbergh’s successful 1927 flight across the Atlantic only six weeks past and the Dole race only six weeks away, the crews of the two planes had finally been given the OK to take off on their race. Although the contest was a major story for San Francisco newspapers, the fliers had to share billing with another aviation event: the Atlantic crossing of Commander Richard E. Byrd, a national hero.

City of Oakland lost credence with the media when it was forced to turn back less than an hour into the June flight because of a faulty altimeter. After quick repairs, with Army mechanics pitching in to help, a second takeoff had to be aborted when Carter complained that his navigator’s windshield was distorted, which would make celestial observations inaccurate. While that problem was being fixed, Carter announced that he would not go along because there was now no hope of beating the Army fliers.

Lieutenants Lester J. Maitland and Albert F. Hegenberger had indeed succeeded in reaching Hawaii safely, landing in Honolulu on June 29. Smith and his sponsors were frustrated at the news — especially since the Travel Air, known to be somewhat faster than the Fokker, had been forced to turn back by an equipment problem beyond their control. Their only consolation was that no civilians had as yet made the crossing, and that the 26 1/2-hour time of the Army fliers still might be beaten in the Travel Air.

The backers quickly announced plans for a second attempt, but one of them, Edmund J. Moffett, withdrew his support and threatened to get a court injunction to keep the plane on the ground. Ignoring Moffett’s threat, the rest of the sponsors went ahead with preparations for a new flight, naming a new manager, Bill Royle, and a replacement navigator. It took time to find the right men, and the choice of Emory Bronte was announced only two days before the flight was scheduled to begin.

As they prepared to face the Pacific, Smith and Bronte made all the safety precautions for the flight that their limited resources would allow. Although no ships had been stationed along their route, word had gone out to merchant vessels to be on the lookout for them. Radio operators ashore and aboard ships at sea were given the frequency of the plane’s receiver and asked to transmit any messages no faster than 10 words a minute to the inexpert operators aboard the plane.

City of Oakland carried an inflatable life raft and supplies for 10 days. It was equipped with a two-way radio to provide both navigational assistance and a safety link. The crew also had carrier pigeons on board, as a precaution and in hopes the birds would intrigue newsmen looking for a new angle to the story. Maitland and Hegenberger, meanwhile, had returned to San Francisco and were receiving a tumultuous hero’s welcome as well as enormous press coverage as City of Oakland‘s flight finally got underway.

The plane was loaded with 367 gallons of fuel, in theory enough for 33 hours of flight at a cruising speed of 100 miles per hour. Although a heavy layer of fog overhung the Golden Gate, the weather was cooperating reasonably well when Smith signaled his readiness to take off that July 14 morning. Maitland and Hegenberger had come to the field and wished their former rivals luck. At 10:03 Smith taxied into position and began his takeoff. After a few hundred yards, however, the plane lurched off the side of the runway, coming to a bumpy stop as one wheel dropped into a foot-deep rut at the edge of the airstrip. Some reports indicate that the plane actually ground-looped.

No one was hurt, and after a half-hour delay, during which the Travel Air was found to be undamaged, City of Oakland went back to the starting point. The plane became airborne at 10:39 a.m. Smith circled the bay to gain altitude before heading west, but the Travel Air was still in the fog when it went over the Golden Gate.

As the flight progressed, City of Oakland seemed to be performing satisfactorily. The radio initially worked well, and even though they could not see the ocean below them the two men felt in close touch with the world. After about two hours, however, the receiver went out. Although they could still transmit, they could no longer receive radio signals as aids to navigation. They also could not speak with rescuers in the event of an emergency.

Shortly after their radio receiver failed, Smith and Bronte released one of the pigeons at the prearranged distance of 200 miles into the flight. About two hours later, 400 miles out, the second bird was released. Two other birds remained on board for emergency communications.

City of Oakland droned westward, flying at an altitude between 3,000 and 4,000 feet most of the time and always with a floor of fog. It performed flawlessly into the evening, and Smith and Bronte sent out a series of optimistic radio messages.

As they were flying only three weeks after the summer solstice, the long evening and twilight effectively minimized the hours of darkness. By the time it was fully dark, the flight was almost half completed. Now the fliers had to battle the drowsiness that came with sitting in a cramped position for long hours, listening to the loud whirring of the engine. They ate some of their food, drank some coffee and scanned the gauges and dials regularly.

Toward morning, the engine began to run more roughly, and the fuel pump gauge showed that fuel had dropped to a dangerously low level. With at least another six hours of flying time ahead of them, Smith and Bronte for the first time became concerned that they might not make it to Hawaii. They sent out radio messages announcing their predicament. Finally, when it appeared that the plane was running out of gas and that they would have to ditch, they sent out an SOS, reporting their position and asking for help from any ships in the vicinity. Then the radio went silent.

Responding to the distress signal, several ships in the area changed course and raced toward the last position transmitted by the fliers. Radio operators in Hawaii and California announced to newspapers that the plane had gone down but that in all likelihood a rescue was imminent.

Smith took City of Oakland down close to the water, intending to ditch while he still had enough gas to permit a powered landing. But as he leveled out just above the water, the engine roared back to life. Hoping that the fuel gauge had simply been malfunctioning, Smith began to climb again to a safer altitude. The plane responded well to his touch, since the fuel aboard now weighed considerably less than on takeoff. While the plane had been close to the sea, however, its radio antenna had dragged in the water and had been carried away. Now the plane could neither transmit nor receive radio messages.

With the coming of dawn the two airmen saw the Pacific Ocean beneath them for the first time. Not long after, they got their first sight of land, the 14,000-foot peaks of Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawaii, off to their southwest. Only then could they feel reassured that Bronte’s navigation had been accurate. Everything now depended on how much gas remained in the tanks.

By that time, SS Wilhemina of the Matson Line had almost reached the spot where they had nearly crashed. As of that moment, no one in the world was aware of City of Oakland‘s location.

After passing well to the north of Maui, Smith maintained course for Oahu, but off Molokai it became clear that they really were running out of gas this time. Crossing the rough northeast shoreline of that island, Smith steered the sputtering plane toward the beaches along the island’s south side. As a gesture of finality, the two men released the last two pigeons, which were supposed to go to their roost on the Big Island (but, like the pigeons released earlier, they never made it home). During the final moments of the flight, Oahu became dimly visible to the west, but it was painfully obvious that they could not reach Honolulu.

With the engine dying, Smith decided against a dead-stick landing on the beach; the sudden stopping of the wheels in the soft sand might result in a ground loop that could pin the men in the plane as it flipped. The alternative was landing in an extensive thicket of kiawe trees, and Smith aimed for them.

The plane was virtually destroyed as it banged into tree after tree before coming to a stop. But since there was no gasoline in the tanks and fuel lines, there was no fire. Miraculously, neither Smith nor Bronte was hurt.

They had brought the plane down near the village of Kaunakakai at 12:16 p.m. Pacific time, 25 hours and 37 minutes after taking off from Oakland. They were about 60 miles short of their goal, Wheeler Field in Honolulu. Maitland and Hegenberger had reached that destination in 25 hours and 43 minutes, and there was clearly no way that Smith and Bronte could have equaled their time by covering that last 60 miles in six minutes. With the plane a complete wreck, the flight was now over except for the formalities.

The people of Kaunakakai alerted authorities on Oahu that the two fliers were alive and well on Molokai. Several Army planes were sent to escort them back to Honolulu, and later that afternoon Smith and Bronte landed at Wheeler Field, where a crowd had gathered to greet them.

The announcement of Smith and Bronte’s safe arrival in the islands was headline news in the San Francisco papers, but their fame was not to last long. Newsmen quickly shifted their attention to the upcoming Dole race. Some officials at first criticized Smith and Bronte for not canceling their distress message, but when it was explained that they had lost their radio antenna, all criticism was withdrawn.

Although the flight is not often cited for its contributions to the development of aviation, there were several features of City of Oakland‘s feat that are worthy of note. First, the flight was well-planned, certainly better than that of the PN-9 in 1925 and better than that of most of the entrants in the Dole race, many of whom took risky shortcuts with basic safety precautions, resulting in the loss of three planes. Second, the Travel Air proved to be a good choice for single-engine transoceanic flying. At the end of August, the winner of the Dole race would fly the same type of plane and have a remarkably trouble-free flight.

The Smith-Bronte flight seemed to point out ongoing problems in estimating gasoline consumption for transoceanic flying that needed to be addressed. Two of the first three planes to reach Hawaii from the U.S. mainland — the PN-9 in 1925 and City of Oakland — had run out of gas. It is also possible that some of the planes lost in the Dole race experienced the same problem, even though most of them carried more gasoline than Smith and Bronte. Were the planners ignoring certain features of this type of flight, such as heavy fuel consumption during liftoff when fully loaded, in their computations? Or did aircraft tend to deviate more from a trackline than ships, thus using additional fuel in corrective course adjustments? It is difficult to understand how Smith and Bronte, with 367 gallons of gas, could have run out in 26 1/2 hours instead of the projected 33 hours.

After the ill-fated Dole race, no one would even try to fly the Pacific to Hawaii for almost a decade. In January 1936, when the flight was again attempted successfully, it was made by Amelia Earhart flying solo from west to east. Flying east, of course, is somewhat easier because the landing site to be located is on a continent, not on a cluster of islands.

While several other great transoceanic flights had ended in crashes near their destinations with no loss of life — including the first nonstop transatlantic flight in 1919, when John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown crash-landed their Vimy in an Irish bog — narrow escapes such as Smith and Bronte’s tended to be regarded by the public and the aviation community as only limited successes. Their luster was dimmed because they involved the loss of a plane and also because the fliers failed to reach their final destinations. Perhaps that is why the accomplishments of Smith and Bronte are frequently overlooked today, even in the San Francisco Bay area.

Smith went on to serve as a pilot during the filming of Howard Hughes’ great aviation motion picture Hell’s Angels before working as a pilot for TWA, eventually becoming a vice president of the airline. Bronte had a long career in business with Tidewater Associated Oil in San Francisco and the Brewer interests in Honolulu. He also saw service as a U.S. Navy pilot in World War II.

Although they had been civilians at the time of their Hawaiian flight, both men received the Distinguished Flying Cross. That recognition notwithstanding, Ernie Smith and Emory Bronte remain largely forgotten today.

This article was written by David H. Grover and originally published in the September 2005 issue of Aviation History. Additional reading: Three-eight Charlie, by Jerrie Mock.