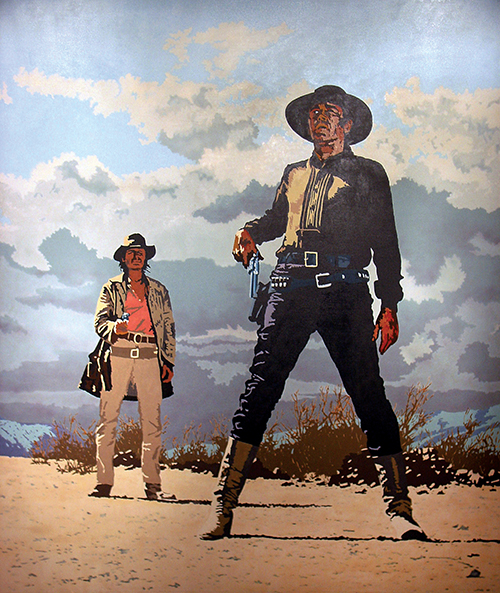

Artist Billy Schenck remembers getting the phone call on Sept. 21, 1991, and being told that gallery owner Elaine Sweet Horwitch had died of a heart attack at age 58. “The first words out of my mouth were, ‘Wow, that is the end of an era’—and it really was,” says Schenck, who was one of the leading painters on the contemporary Western art scene that exploded in the 1970s.

With galleries in Scottsdale and Sedona, Ariz.; Santa Fe, N.M.; and Palm Springs, Calif., Horwitch played a key role in bringing the Southwest pop movement to the American consciousness. “She was easily the most significant dealer that ever lived outside of New York or L.A.,” Schenck says. It’s no wonder, then, that the artists she represented feature large in “Southwest Rising: Contemporary Art and the Legacy of Elaine Horwitch,” a tribute running through June 21 at the Tucson Museum of Art.

“Some of the art we’re showing is rather tame,” chief curator Julie Sasse admits, “but at the time it was radical, it was different, and art collectors were rejecting it as way too out there—and some still do.” It would be hard to find someone better suited to curate the show, as Sasse worked for Horwitch for more than a decade, ultimately becoming the gallery owner’s managing director. “Because I stayed in the business and stayed in touch with many of these artists, I kind of knew where everybody was, and everybody kept in touch with me.”

The project started out as a book, Sasse explains, after artists prompted her to relate the story of Horwitch and that dynamic art movement. “It was such a good story,” the curator says. “It was sort of like Paris in the ’20s in Santa Fe, a little renaissance happening in New Mexico and even in Scottsdale.” The companion book shares the same title as the exhibit and was co-published by Cattle Track Arts & Preservation and the Tucson Museum of Art. “Well, I thought it was going to be maybe a 250-page book and it ended up being 550,” Sasse says with a laugh. “I thought I could bang it out in a summer, and it took four and a half years and two residencies.”

As a gallery owner, Sasse says, Horwitch “liked irreverence. She presented art on her own terms, and she didn’t follow anyone’s strong terms of what should be shown alongside each other. Not all the artists liked that. They didn’t want their art shown alongside a howling coyote, but she was like, ‘Nope we’re going to show all of this.’” For “Southwest Rising” Sasse tried to include as much as she could. “You don’t have to follow stereotypes. You can see the desert or the Southwest or the mountains or cowboy art or anything through a new perspective and still retain some of the essence that makes the region worthy of focus.”

The exhibit features more than 100 artists, including Schenck and other standouts from Southwest pop’s 1970s heyday through the early 1990s, including Anne Coe, John Fincher, James Havard, Louise Nevelson, Tom Palmore, Robert Rauschenberg, Larry Rivers, Fritz Scholder, Lynn Taber and Bob Wade. Even the legendary Georgia O’Keeffe was part of the movement. Auxiliary galleries present the works of regional artists known for their contemporary Southwestern art, including Philip C. Curtis, Harmony Hammond, Richard Hogan, Paul Pletka, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and Emmi Whitehorse.

The Booth Museum in Cartersville, Ga.; the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe; and the James Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida, also plan to pay tribute to Horwitch, showing works from their own collections and borrowing from other sources. Tucson has the honor of taking the lead.

“They all have some of the same artists in this exhibition,” Sasse says. “In a way it’s gotten longer legs, because instead of seeing the exact same pieces, people are getting to mine from their collections.”

“I just don’t want these people to be forgotten,” Sasse says. WW