In 1937 Edward R. Murrow sailed with his wife, Janet, to London where he was to take up the post of chief CBS radio correspondent in Europe. At the time, Murrow had never written a news story in his life, and he had never made a scheduled radio broadcast. He was 29 years old.

During the next three years, Murrow would oversee the birth of foreign news broadcasting, and he would make his own clipped baritone voice one of the most recognized by his countrymen. More important, Murrow, utilizing the new medium, would report from beleaguered London during the Blitz of 1940, dramatizing Britain’s stand-alone defense against Adolf Hitler to an America that slowly rallied to England’s cause. In so doing, he virtually invented modern broadcast journalism.

Murrow was a somewhat unlikely champion for the British. He had traveled to England before, but had been thoroughly unimpressed and later told one English audience: ‘I thought your streets narrow and mean, your tailors over-advertised, your climate unbearable, your class-consciousness offensive. You couldn’t cook. Your young men seemed without vigor or purpose. I admired your history, doubted your future.

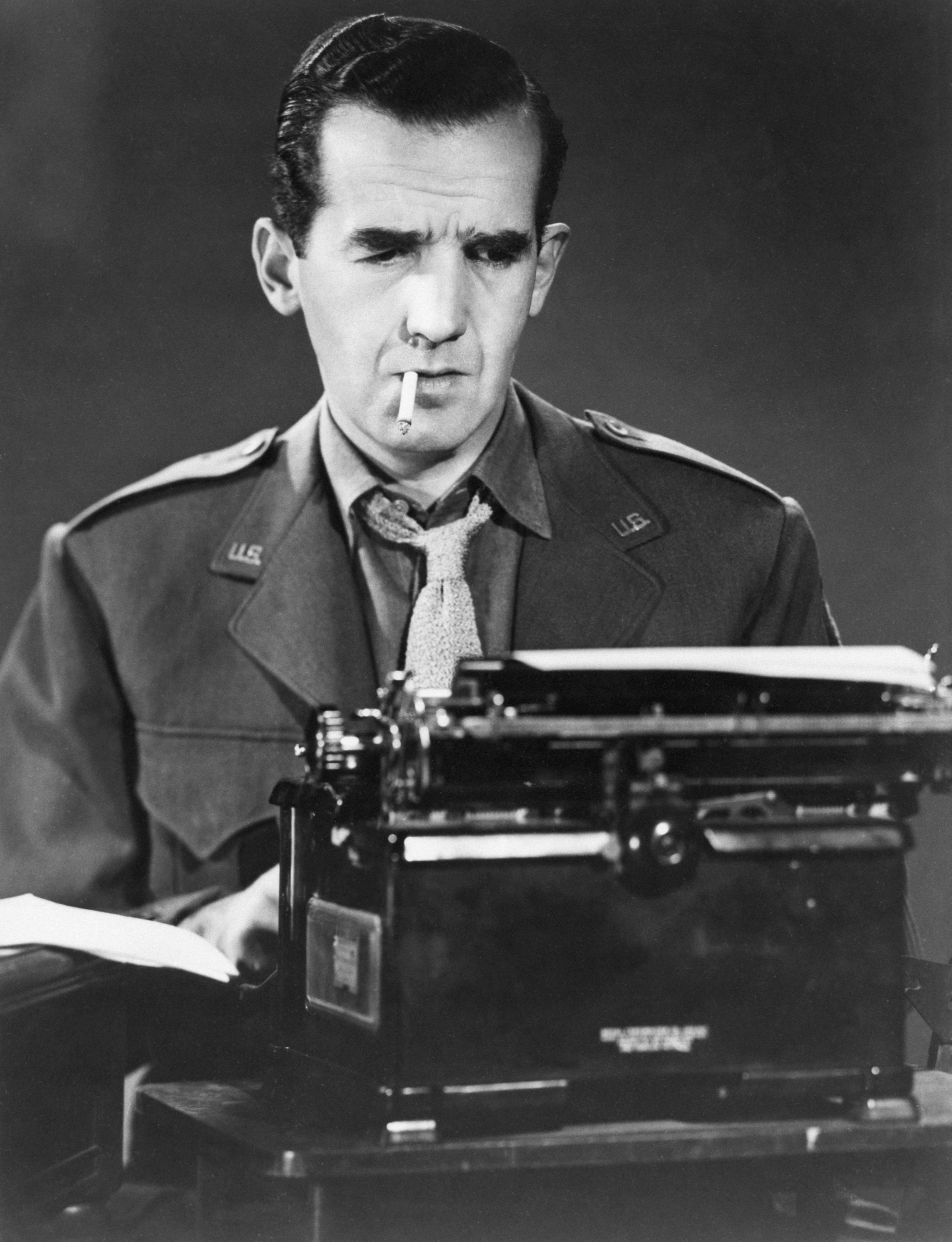

NATIONAL ARCHIVES |

| From behind a CBS studio microphone and eventually from on the scene, Edwar R. Murrow presented live word pictures of Londoners’ life in underground subway station shelters while German bombers ignited the city above. |

Edward R. Murrow was that peculiarly American thing, a self-made man. In Britain during the war, London hostesses came to regard him as a prized dinner guest — handsome and intelligent, an elegant dresser who displayed an understated wit that appealed to local tastes. But there was little in his background to suggest such style and panache. Murrow was born Egbert Roscoe Murrow on April 24, 1908, in Polecat Creek, N.C., a place no more sophisticated than its name might suggest. When he was young, his family moved to Blanchard, Wash., a small logging town near the Pacific. In high school the self-making began with a self-naming. He dropped the Egbert and eventually re-christened himself Edward R. He worked at timbering during summers while in high school and for a year after graduation to secure the funds to attend a Washington state college.

When Murrow entered college, the field of foreign radio correspondence did not exist. Still, his undergraduate interests did much to prepare him for his future work. His best subjects were speech, debate and ROTC. He was a natural leader; on graduation he became president of the National Student Federation, through which he met his future wife, Janet Brewster. He took an interest in European politics, uncommon in young Americans at the time. At age 25, he worked for a tiny organization that attempted to relocate persecuted scholars from Germany to the United States. In 1933 fear of Hitler in the United States was not great, so funds were limited and visas difficult to obtain. Still, the 335 refugees brought to the States included novelist Thomas Mann, theologian Martin Buber and philosopher Herbert Marcuse. All this was in Murrow’s background when he went to Europe in 1937.

If war was to be Murrow’s coming-of-age, it was also the coming-of-age of radio. Murrow’s lack of reporting credentials meant little when he went to London in 1937. He was sent to the British capital to be director of talks, and his task was to schedule interviews with notables from government, business and the arts. At the time, CBS did not report the news from London; CBS, and radio generally, barely reported the news from New York. News coverage was largely limited to radio commentators, like H.V. Kaltenborn, and to announcers who read the headlines on the hour. It was the Depression, and the public turned to radio not for news, which was mostly bad, but for escape — the humor of Jack Benny and Burns and Allen and the singing of Bing Crosby and Kate Smith.

Murrow was among the first to see serious journalistic possibilities in the airwaves. In August 1937, Murrow decided to hire an itinerant American journalist as CBS’ man on the Continent. The reporter, William L. Shirer, having fled Prohibition-era Iowa for a place where a man could drink a glass of wine or a stein of beer without breaking the law, had been knocking about Europe for a decade. By chance, on the same day that Shirer was laid off from his post as a correspondent for Universal Service in Berlin, Murrow offered him a job. Shirer accepted, but a hurdle remained. With CBS brass listening in from New York, Shirer made a voice audition. His speaking voice was Midwestern, nasal and flat, and CBS executives thought he was terrible. Murrow put his foot down: He was not hiring announcers, he said, but people who could think and write. That was Murrow’s personal standard, and Shirer was the first to meet it.

(The issue would resurface in 1939, when Murrow wanted to hire a young American newspaperman who had gone to Paris in 1937 to be near the war that he, though few others, expected. Not wanting to be a famous war correspondent named Arnold, the young journalist dropped his first name and presented himself to the world as Eric Sevareid. His voice audition was worse than Shirer’s. Shirer had been monotone; Sevareid was a mumbler. So he was, and — hired at Murrow’s insistence — so he remained through an illustrious four-decade-long broadcast career.)

Events pressed the new medium into a new role. On March 12, 1938, Shirer traveled to Vienna — coincidentally, the same day the Germans were marching in, adding Hitler’s native country to his Nazi state. The day’s top story had landed in Shirer’s lap, but he could not report it. German officials refused to let him broadcast and escorted him out of the radio station.

At Murrow’s suggestion, Shirer flew to London to report his story on air from there. Murrow then headed for Vienna to cover subsequent events. From New York, CBS news director Paul White called Shirer to say he wanted reports from London, Vienna, Paris, Berlin and Rome, using American newspaper correspondents: A half-hour show, and I’ll telephone you the exact time for each capital in about an hour. Can you and Murrow do it? I said yes, Shirer recorded in his diary, and we hung up. The truth is I didn’t have the faintest idea.

In eight hours, and on a Sunday, Murrow and Shirer lined up newsmen to make reports, found the needed shortwave facilities and went on the air — live. The broadcast, a great success, soon became a standard feature. Shortly thereafter, Shirer recorded in his diary: The [Austrian] crisis has done one thing for us. Birth of the ‘radio foreign correspondent’ so to speak.

The basic forms were set early. Correspondents would write their stories, clear them through censorship, then go to a government-operated shortwave facility to transmit them live back to CBS in New York. The programs sounded more organized than they were. In New York, announcer Robert Trout might say, We take you now to William Shirer in Berlin. In Berlin, Shirer could not hear Trout’s voice; rather, he simply started speaking live into a microphone at an assigned time.

The seizure of Austria was bad news; worse news followed. The Western democracies deserted Czechoslovakia at Munich. Murrow had a world scoop on the settlement, but took little consolation in it. He was not so much a newsman as a citizen of the world. The rise of Hitler was, to him, less a story to be covered than an unraveling catastrophe he could do little to stem. Post-Munich, Murrow met up with Shirer in Paris, where the pair tried without success to drink themselves into a better frame of mind.

America seemed largely indifferent. To Murrow, it was as though the greatest drama in history was playing to an empty and deserted theater. In July 1939, Shirer was briefly back in New York. His wife, Tess, told him he was making [him]self most unpopular by taking such a pessimistic view [of Europe]. They know there will be no war. And Americans clearly wanted none. At year’s end, more than 95 percent of Americans polled were against war with Germany. By then Poland had fallen. In April 1940, Denmark and Norway followed. In May, German tanks rolled into the Netherlands, Belgium and France, with resistance quickly subdued. On June 22, the French surrendered at Compiègne, an event for which Shirer again gained a world scoop. With the French surrender, England stood alone.

England’s future was never more in doubt than in the summer and fall of 1940 when Hitler, master of the Continent, unleashed his Luftwaffe on Great Britain, his sole opponent still standing. For Murrow, nothing less than the future of civilization was at stake in that battle. For millions in America, news of that conflict came each evening in a report that began with Murrow’s signature phrase, This…is London.

England’s south coast awaited invasion. In Berlin two Nazi officials placed bets with Shirer: The first wagered that the German swastika would be flying over Trafalgar Square by August 15; the second said by September 7. Along the French and Belgian coasts, the Germans concentrated the small craft — 1,700 by mid-August — with which they planned to transport the initial invasion wave of 90,000 soldiers and 650 tanks. In London a newspaper vendor posted a placard that typified English resolve: We’re in the final. And it’s on the home pitch.

The German attack had two phases. In the first — lasting from mid-August to early September 1940 — the Luftwaffe sought to destroy the Royal Air Force. If the RAF was defeated, it could not provide air cover for the British navy, which would then be forced to withdraw from the English Channel. A German crossing would follow. In Germany, invasion planning proceeded. On September 2, Shirer noted that German press officers had removed a gigantic illuminated map of France that had been used to help reporters track the invasion of that country. That map has been taken down, Shirer reported, and an equally large one substituted. It was a map of England.

From opposite sides of the Channel, Murrow in London — assisted by his colleague, Larry LeSueur, another of Murrow’s young hires — and Shirer in Berlin tracked the first battle in history to be fought solely in the air. Or at least they tried. All acknowledged that with aircraft so small flying so high, it was all but impossible to tell what was happening. Though many current military historians believe the Luftwaffe was gaining an edge, Hitler was impatient; he wanted the invasion to be accomplished by late September, before the October fogs cut visibility in the Channel. He decided that bombing civilian London would quickly cow the British.

On September 7, wave after wave of German bombers struck London in a 12-hour attack. Murrow was southeast of the city, trying to get a bead on the action. He interviewed Englishmen in a variety of places, including spending part of the day near an RAF air base. After writing his script, the following day he broadcast live from the studio: On the airdrome ground crews swarmed over those British fighters, fitting ammunition belts and pouring in gasoline. As soon as one fighter was ready, it took to the air, and there was no waiting for flight leaders or formation. The Germans were already coming back, down the river, heading for France. He spoke of the hollow grunt of the bombs, [the] huge pear-shaped bursts of flame. He talked to a pub owner who told us these raids were bad for the chickens, the dogs and the horses. And for a time, he simply took cover, hunkering down with Vincent Sheean, an American writer whom Murrow pressed into service from time to time, and Ben Robertson of the short-lived New York newspaper PM. As Murrow described it: Vincent Sheean lay on one side of me and cursed in five languages….Ben Robertson…lay on the other side and kept saying in that slow South Carolina drawl, ‘London is burning, London is burning.’ London, indeed, was burning. Four hundred were dead, triple that many injured, and fires blazed throughout the city.

London’s stand against the bombing became the focus of world attention; eventually, 120 reporters — a huge number at the time — came to the British capital to report it. Murrow stood out as unmatched. This was so, first, because of the manner in which he portrayed the English — not as heroes but as human: unflappable, dogged, quirky. He reported how life among the many citizens continued after the bombing of residential London began: Walking down the street a few minutes ago, shrapnel stuttered and stammered on the rooftops and from underground came the sound of singing, and the song was ‘My Blue Heaven.’

He reported on Londoners’ solidarity in the shelters, but noted that even there, the rich fared better than the working classes. He spoke of a cluster of old dowagers and retired colonels who took refuge at the Mayfair Hotel. There, he remarked, the protection was not great, but you would at least be bombed with the right sort of people. He reported on casual courage. He described an official adding a name to a list of firefighters killed battling fires the bombing had caused. The list, Murrow noted, contained 100 names.

Added to Murrow’s empathy for the British people was his mastery of language. He was, his colleague Sevareid said, the first great literary artist of a new medium. Murrow, through reflection and intuition, had a keen appreciation of broadcasting’s power and nature. Radio, he said, was essentially intimate. It was not an announcer speaking to an audience, but Murrow as an individual speaking to fellow individuals who had gathered by their Philcos in living rooms in Kansas or New Hampshire. He believed that radio was visual, and he had a gift for the evocative phrase. When Winston Churchill was made prime minister, Murrow introduced him as Britain’s tired old man of the sea. Knowing that moonlight made London more visible to attacking aircraft, he referred to one night sky as being brightened by a bomber’s moon.And Murrow believed that radio’s task was not to bring the story to the listener, but to bring the listener to the story.

On August 24, two weeks before the On the airdrome program, he had made a remarkable nighttime broadcast from London’s Trafalgar Square, standing just outside the entrance to a bomb shelter. Live and unscripted, his words painted the scene: the searchlights splashing white on the bottom of clouds; a red double-decker bus — most of its lights extinguished in the blackout — passing like a ship at night; a driver calmly stopping for a red light on a totally deserted street. Murrow said he could see almost nothing in the blackout. But he could hear something. Bringing his listeners to the scene, he lowered the microphone to street level so that people in America could hear the footsteps of Londoners taking shelter from bombs.

Through it all, Murrow was battling on a second front. That August 24 coverage of the bombing had raised questions about the propriety of such live, on-the-scene reporting of the attacks. As bombing continued, Murrow pressed British officials hard for permission to do regular, unscripted, live, on-the-street broadcasts of the events. Initially, British officialdom was dismissive — Murrow was not even a citizen, and live broadcasts could give valuable information to an enemy that would presumably be listening in. Murrow pressed the matter, explaining that his broadcasts would be transmitted from his microphone through the BBC headquarters, where they would still be subject to censorship. More important, he gained an ally, Prime Minister Churchill. Forty years earlier Churchill had been a correspondent in the Boer War, and he had a newsman’s residual compassion for getting the story out. More to the point, he believed that anything done to dramatize London’s struggle would build American sympathy for England’s cause.

By mid-September, Murrow gained permission. With the live broadcasts, he became the star of his own drama, standing exposed on rooftops. The sounds of bombs exploding near him were clearly audible. In narrow terms, the work was quite remarkably dangerous. In broader terms, his accounts of a city under siege made compelling listening. Murrow’s reports from London helped make radio America’s dominant news media. In one 1940 survey, 65 percent of respondents said radio was their best source of news. His own audience grew to 22 million, reportedly including President Franklin Roosevelt and members of his cabinet. Many were swayed by what they heard. During September 1940, the bombing’s first month, the share of Americans telling Gallup pollsters that their nation should aid Britain increased from 16 to 52 percent. That month, President Roosevelt went to Congress to repeal the Neutrality Act that barred military support to the British.

Hitler had good reason to believe that the bombing of civilian London would soon break Britain’s will to resist. Prewar, most military experts held that aerial bombardment would quickly devastate any city. In 1932 British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin had famously stated, The bomber will always get through — a remark that did little to bolster British self-assurance. As events in London and elsewhere were to prove, such bombing more generally strengthened than broke resolve. The London Blitz was, however, the first sustained bombing of a major city. And when, contrary to expectations, that city did not fall, respect for its stand grew. Murrow shared the sentiment, and he broadcast that admiration. From one bombed location, he reported: The girls in light, cheap dresses were strolling along the streets. There was no bravado, no loud voices, only a quiet acceptance of the situation. To me those people were incredibly brave and calm.

London sent its children to the countryside, ate powdered eggs rather than fresh ones and endured the nightly attacks, sleeping in bomb shelters. At year’s end, Londoners were underfed, under-rested and under bombardment. Murrow’s December 29 broadcast caught the grimness of the hour: No one expects the New Year to be happy. We shall live hard before it is ended. The immediate problems are many and varied: Something must be done about the night bombers and the submarines; improved facilities for life underground must be provided. He added: Probably the best summary — written by Wordsworth [when England was at war with Napoleon] in 1806: ‘Another year, another blow, another mighty empire, overthrown, and we are left, and shall be left, alone, the last that dared to struggle with the foe.’

The bombing affected people strangely, noted Sevareid, who joined Murrow in London after the fall of France. Those who were walking when the first bombs dropped would halt. Those who were standing would begin to walk. Murrow once awakened CBS correspondent LeSueur, who was bunking at the Murrow’s, with the news that the building was on fire. LeSueur picked up his clothes and walked into a closet to get dressed.

Murrow refused to go into shelters, saying that once you did you lost your nerve. With considerable nonchalance, Murrow, LeSueur and a young New York Times reporter, James Reston, played golf on a nine-hole course on London’s Hampstead Heath. If a ball rolled near an unexploded bomb, it was declared an unplayable lie.

The hazards were all too real. Out walking one evening, Murrow suddenly stepped into a doorway. Two colleagues instantly followed suit. Seconds later, a shell casing landed where they had been standing. CBS was repeatedly bombed out of its tiny London office — always without serious casualty. Another evening, Ed and Janet Murrow were walking home and he suggested stopping in the Devonshire Arms, a pub frequented by journalists. Janet said she was tired, so they continued home. Ten minutes later the pub received a direct hit — and everyone inside was killed.

Sevareid did not share that bravado. He lived a few blocks from the BBC, and wrote: To get to the underground broadcasting facility meant a walk of a couple blocks for me. I would shuffle cautiously through the inky blackness to each curbing where the guns would make the crossing street a tunnel of sudden, blinding light. [Then,] I would plaster myself against the nearest wall, and, however sternly I lectured myself, I not infrequently found myself doing the last 50 yards at a dead run.

If Murrow was not frightened, he was nonetheless exhausted. Sleeping little, eating less and smoking four packs of cigarettes a day, he was driven by his sense of the importance of the event. Among other problems, Murrow had to reconcile his own views with CBS’ strict policy of nonpartisanship. In part he did this simply by presenting the British as the underdog, relying on his countrymen’s natural sympathies to take England’s side. Further, however, he was inclined to attribute his own point of view to others, then report it as news. He spoke of the attitudes of unnamed Englishmen who, he said, had given up on the notion that victory could be achieved without American aid. Now, Murrow reported, such Englishman had come to admit: British victory, if not British survival, will be made possible only by American action. There are too many Germans, and they have too many factories. It seems strange to hear English, who were saying, ‘we’ll win this one without America,’ admitting now that this world — or what’s left of it — will be largely run either from Berlin or from Washington.

Of Murrow’s influence, Sevareid later wrote: The generality of British people will probably never know what Murrow did for them in those days….Murrow was not trying to’sell’ the British cause to America; he was trying to explain the universal human cause of men who were showing a noble face to the world. In so doing he made the British and their behavior human and thus compelling to his countrymen at home.

The German air assaults varied in intensity. The strength of the attacks depended in part on the demands made by German operations elsewhere and, apparently, by Germany’s periodic shortage of lubricating fluids for its aircraft. After a lull, the Luftwaffe returned in April 1941. Murrow reported: They came over shortly after blackout time, and a veritable show of flares and incendiaries. One of those nights where you wear your best clothes, because you’re never sure that when you come home you’ll have anything other than the clothes you were wearing. Given the size of the city, Murrow added, it was difficult to judge the severity of an attack from one’s own vantage. If the bombs fall close to you, he added: You are inclined to think the bombing is very severe. Tonight, having been thrown against the wall by blasts — which feels like nothing so much as being hit with a feather-covered board — and having lost our third office, which looks like some crazy giant had been operating an eggbeater in its interior, I naturally conclude that the bombing has been heavy. Actually, it was the heaviest single attack of the war. The following month, CBS lost its fourth office.

Toward the end of 1941, Murrow returned to New York to receive what one observer called the greatest welcome given a journalist since Henry Morton Stanley returned, having found David Livingstone. One thousand gathered for a testimonial dinner at New York’s Waldorf Astoria. There, poet and Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish praised Murrow’s work: But it was not in London really that you spoke. It was in the back kitchens and the front living rooms and the moving automobiles and the hotdog stands…that your voice was truly speaking. What Murrow had done, MacLeish added, was to destroy the belief that what happened 3,000 miles away was not really happening. You burned the city of London in our houses and we felt the flames that burned it. You laid the dead of London at our doors and we knew the dead were our dead — were all men’s dead….Without rhetoric, without dramatics, without more emotion than needed be, you destroyed the superstition of distance and of time.

Murrow’s own remarks were those of a man making a case. He told the audience: If you were in London now, you would be surprised at the number of people who would say to you, ‘Tell your fellow countrymen not to make the same mistakes we made. We didn’t want anything of this world except to be let alone — until it was almost too late.’ And, again making reference to thoughtful Englishmen, Murrow used the podium to issue a challenge: The question most often asked by thoughtful Englishmen is this: ‘If America comes in, will she stay in? Does she have any appetite for the greatness that is being thrust upon her?’

On the night that dinner was held — December 2, 1941 — America’s role in the conflict was still unsettled. Five days later, in an act that astonished Murrow, Pearl Harbor was bombed, and America was at war.

With the United States at war, Americans leaned more strongly into the day’s events. CBS expanded its European news team. In time, those reporting with Murrow included many who would make great careers in broadcasting: along with Shirer, LeSueur and Sevareid were Charles Collingwood, Howard K. Smith, Richard C. Hottelet, Cecil Brown, William Downs and Winston Burdett. When Murrow hired them, they were little more than kids — bright boys in their mid-20s — as inexperienced at radio news reporting as Murrow had been. They did, however, meet Murrow’s personal standard: They could think and they could write. And most modeled their approach to gathering the news on Murrow’s approach. Customarily, their reports would be part fact, part essay, part color and part editorial, all wrapped up in a crisply written two- or three-minute account that became the standard format for CBS journalism. Many others in the field regarded their work as the best ever done in broadcasting.

Murrow, who defined their task and directed their efforts, never made any great claims for himself — not for his efforts during the Blitz, or for what followed. Writing to Charles Collingwood in the immediate postwar period, Edward R. Murrow said, For a few brief years a few men attempted to do an honest job of reporting under difficult and sometimes hazardous conditions and they did not altogether fail.

This article was written by Mark Bernstein and originally published in the June 2005 issue of American History Magazine. For more great articles, subscribe to American History magazine today!