Union officer struck ‘Boy General’ in the head with a saber during Rebel surrender at Nashville

[divider_flat]ON A WINTER DAY in 1876, former Confederate Brig. Gen. Thomas Benton Smith armed himself with a bow and arrows, mounted a horse, and rode near Nashville “attacking everyone he met.” Among the 37-year-old veteran’s victims was his cousin, struck in the leg with a steel-tipped arrow. “Imagining himself to be the Indian Emperor of America,” Smith fled into the hills around the city, where he finally was captured with “great difficulty” and jailed.

[divider_flat]“He deserves too much from his State to be sent as a common thief to jail,” a Nashville newspaper wrote about Smith’s arrest, “and it is a shame upon the laws that makes no distinction between a thief and a lunatic.”

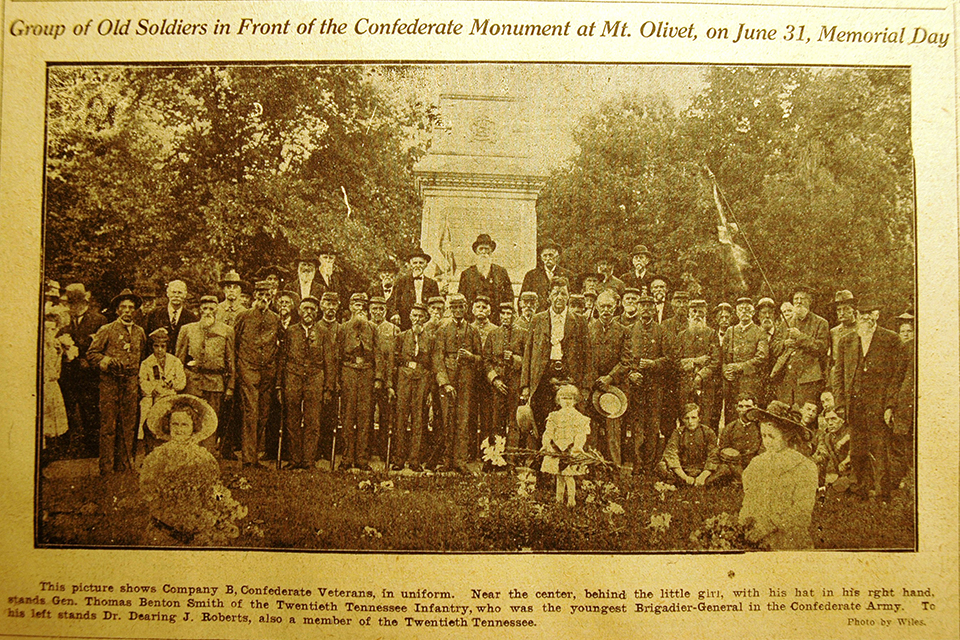

(Courtesy Tennessee State Library and Archives)

Obviously unwell, the Tennessee native was committed by his sister to the Central Hospital for the Insane in Nashville, a foreboding, castle-like building southeast of the city that was finally demolished in 1999. From 1876 to 1923, Smith was confined there, reportedly leaving only once or twice a year for Confederate veterans’ reunions. In the years after his confinement, Smith was described as a “pathetic figure,” “incurably ill,” and “demented.”

After Smith was committed, the reunions became the highlights of his life. At an early–20th century event, he became a commander again, running old soldiers through drills from the Hardee’s Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics manual. Although he suffered from depression, “General Smith was self-poised” that day, according to an account, “as full of the animation of the old days as could be imagined.” Despite his dementia, the lifelong bachelor showed off a “remarkable memory” at another reunion by calling all his old comrades by name. But at another gathering of Confederate veterans in 1901, Smith bemoaned his circumstances. “This is the only free day I have in the year,” the 63-year-old told an acquaintance. “All of you should be happy, for you are free every day. When this day is ended, I will have to go back to those terrible prison walls.”

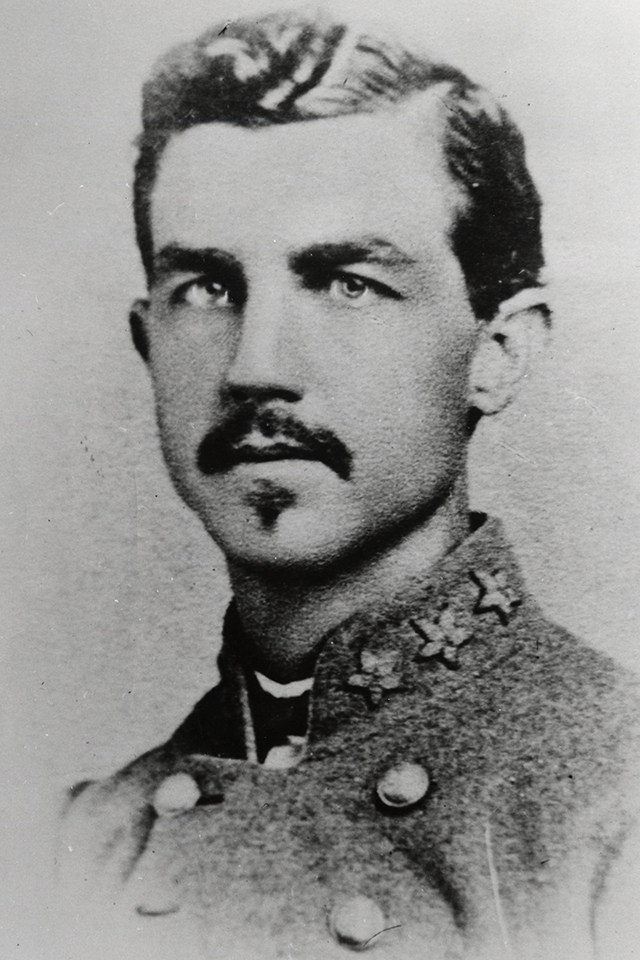

How did the once-promising life of Thomas Benton Smith—who rose from captain in the 20th Tennessee Infantry to colonel and in July 1864, at age 26, to “boy general” in the Army of Tennessee—take such a terrible turn? For the answer to that question, go back to another gloomy day—December 16, 1864, atop a hill near Granny White Pike during the Battle of Nashville.

Outgunned, outmanned perhaps 3-to-1, and nearly surrounded on the rainy, cold afternoon, the Confederates atop Compton’s Hill (Shy’s Hill) were desperate. In command of a brigade in Maj. Gen. William B. Bate’s Division, Smith had somehow held out, leaving the steep hillside strewn with Federal dead and wounded. But it was obvious he had no chance of victory, and about 3:30 p.m., a portion of the line occupied by his soldiers gave way. Smith removed a handkerchief from his pocket, waved it above his head, and ordered what remained of his command to cease fire. The surrender was inevitable.

“The enemy,” Union Army of the Cumberland commander Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas wrote, “was hopelessly broken.”

Explained Army of Tennessee commander Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood in his after-action report: “The position gained by the enemy being such as to enfilade our line caused in a few moments our entire line to give way, and our troops to retreat rapidly down the pike in the direction of Franklin, most of them, I regret to say, in great confusion, all efforts to reform them being fruitless.”

Besides losing 54 cannons Hood lost more than 1,500 soldiers as POWs, including Smith. As the general was marched to the rear, perhaps

down Granny White Pike north toward Nashville, a Federal officer approached him. Drunk or simply incensed by his own losses in the battle—no one knows for sure—Colonel William L. McMillen struck Smith violently on the head with a saber.

McMillen was a former Union army surgeon and commander of the 95th Ohio Infantry, but he was serving in brigade command at Nashville. He would attack Smith, standing a little over 6 feet tall, at least twice more.

“I am a disarmed prisoner!” Smith cried out to no avail during the beating. Private Monroe Mitchell, one of at least two 20th Tennessee soldiers who witnessed the sad event, recalled in 1891:

“Gen. Smith had just gotten through a gap in a rock fence, when I saw a Federal Major [sic], his rank being indicated by his uniform, approach him. This officer was a man probably of 150 pounds in weight and perhaps 5 foot 11 inches or thereabouts. He was very angry and said to Gen. Smith, ‘Come here, you d—-d rebel s– of a b—-. Here you are living, and (he called some Federal Colonel’s name which I did not catch) is dead or dying!’”

Mitchell noted that the first blow by McMillen knocked off Smith’s hat. The blows were so hard, in fact, the weapon quickly became bent. “Yes, God damn you, I mean what I say,” McMillen yelled. According to Mitchell, embellishing perhaps, Smith fell to his knees but remained “perfectly erect and calm while receiving the blows.”

Rushed to a Federal field hospital, Smith was examined by a surgeon, who gave him no hope of surviving. “Well, you are near the end of your battles,” he said, “for I can see the brain oozing through the gap in your skull.”

Smith, who would miraculously survive the brutal at-

tack, was sent first to a Federal prison in Nashville. Later, he was held at Johnson’s Island in Ohio and then at Fort Warren in Boston. In a plea for his release, Smith wrote to President Andrew Johnson in June 1865: “I…have been severely wounded several times, lost killed the only brother I had, and am the only son of an aged widowed Mother, who is in moderate circumstances.”

Released on July 24, 1865, Smith returned home, but the effects of the brutal, unwarranted and cowardly attack in Nashville haunted him the rest of his life.

After the war, Smith ran for Congress in 1870 (he lost) and worked in various roles for the railroad, including as a conductor. But he eventually was crippled by bouts of depression, perhaps caused by the severe brain injury suffered in the 1864 attack, and could not take care of himself. He lived with his mother, Martha, until she died.

Sometimes, Smith was blunt with others about his mental health. While wandering the grounds of the asylum one day, he encountered a hunter. After Smith asked to examine his weapon, the young man handed it to the old soldier, who checked the ammunition. “You have done a foolish thing. You have put a loaded gun in my hands. I live over there,” the veteran told the hunter, pointing to the asylum, “and I’m crazy—at times. I might shoot you. Don’t ever give your gun to a stranger.” Then he returned the weapon to the man.

Most of the time Smith was “perfectly rational,” according to a newspaper account, “although occasionally he has an attack of homicidal mania.” In 1903, Smith aided rescuers during a fire at his asylum—“One of the heroes of that night,” the local newspaper called him. Four years later, the Nashville Tennessean published a lengthy feature about Smith under a seven-column headline “A Gallant Confederate Soldier Who Suffered Worse Than Death.” The story noted:

“Although for nearly thirty years Gen. Smith has been in retirement, he is still in the most affectionate remembrance by those of his comrades who are still living. This fact alone seems a guaranty of his noble courteous nature, as well as his invincible spirit. Whenever the name of this brave Confederate soldier is mentioned the men who spent four terrible years fighting by his side seem eager to add to his meed of praise. They all love ‘Tom Smith’ and seem to think it particularly hard that he should have been singled out as the victim of fate’s cruel trick.”

In 1917, at the height of World War I, a former Confederate from Tennessee lamented the beating Smith took at the hands of McMillen, whom he likened to a then-hated “German soldier.” In a letter to the editor of the Tennessean, the veteran wrote that the U.S. government should “atone in some way for…this great wrong on an honorable and defenseless soldier, fighting for his country in a cause he believed to be just and right. It is none too late to do the right thing.”

Although there is no known record of the government doing the “right thing,” the Grand Army of the Republic post in New Orleans reportedly revoked McMillen’s membership when it got wind of his barbarous treatment of Smith during the war. Perhaps that brought the general a small measure of satisfaction. McMillen, who had moved to Louisiana in 1866 to make his postwar fortune as a cotton planter and “carpetbagger” politician (both unsuccessfully), died in Ohio in 1902.

“Is it possible that this cowardly wretch could have been anything other than a Yankee bounty jumper,” an early 20th Tennessee regimental historian wrote about McMillen, “or perhaps a Southern deserter? One is as good as the other.” (McMillen, in fact, was accused of cowardly conduct for actions during a battle near Richmond, Ky., in 1862. He was court-martialed but acquitted.)

Smith outlived his Civil War tormentor by 21 years, dying at 85 of heart failure on May 21, 1923, at the insane asylum that was his home more than half his life. He was among the last Confederate generals to die. “A military genius, General Smith ended his days in a madhouse,” the Tennessean reported, “after 47 years of confinement more lonely than ever was Napoleon at St. Helena.”

In Nashville, the general’s passing was a major event, meriting Page 1 coverage in the newspaper. A service with military honors was held for Smith at the state capitol. Facing each other, two solemn guardsmen stood at parade rest near his casket there, “the gleam of their sky-pointed bayonets creating a shaft of light through the darkness.” The bier was draped with two flags—the Stars and Stripes and Stars and Bars. Confederate veterans served as honorary pallbearers.

“I was often at reunions with him,” a gray-bearded 20th Tennessee veteran who sat near Smith’s coffin at the service told a reporter. “I loved him; we all loved him.”

A prisoner no more, Smith was buried in Nashville’s Mount Olivet Cemetery.

John Banks, a frequent contributor to America’s Civil War and the author of two Civil War books, writes from Nashville, Tenn. He is also author of a Civil War blog (john-banks.blogspot.com).