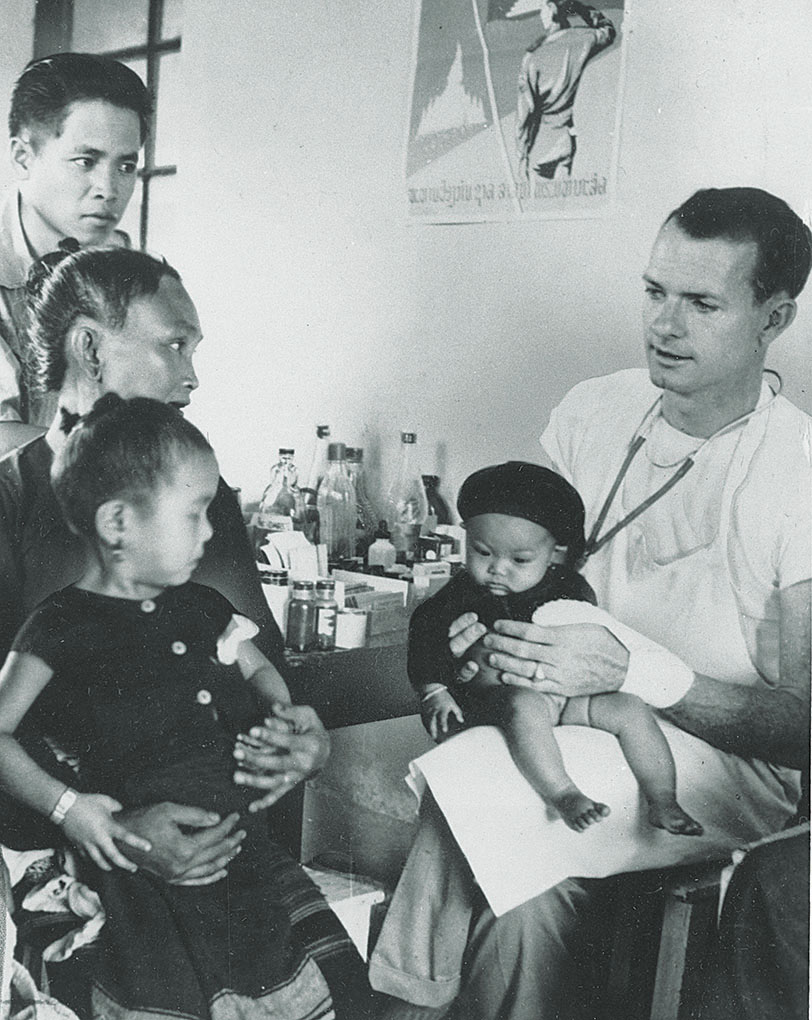

Throughout the mid-to-late 1950s, Dr. Thomas Anthony Dooley III was widely celebrated as embodying the great and unselfish good of American aid. His humanitarian medical assistance in rural areas of Laos and Vietnam during the early U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia was widely praised. President John F. Kennedy awarded Dooley, who died in 1961, a posthumous Congressional Gold Medal. There was a movement to have Dooley, a Roman Catholic, canonized as a saint.

Yet there was a hidden side to Dooley, U.S. government records revealed later. After World War II, when U.S. foreign policy focused on containing communism, Dooley was the consummate “cold warrior.” He assisted the CIA by gathering intelligence on North Vietnamese operations in Laos and South Vietnam, while creating and promoting U.S. “disinformation” as a CIA propaganda weapon in the struggle for Vietnamese “hearts and minds.”

Today all thought of sainthood has vanished, leaving in its place a legacy of contradictions and controversy.

Strict Roman Catholic

Dooley was born in St. Louis on Jan. 17, 1927. His parents were strict Roman Catholics, and after high school he studied at one of American’s most famous Catholic universities, Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana, but dropped out after five semesters. In 1944 as World War II raged, Dooley joined the Navy. He became a Navy corpsman and was stationed at a naval hospital in New York City. After the war, Dooley left the Navy and returned to Notre Dame in 1946, but dropped out again. Dooley never revealed why he entered and left twice, except to say he was “restless.”

Afterward Dooley entered St. Louis University School of Medicine to become a doctor. The university today states that it graduates doctors who “appreciate humanistic medicine, concern themselves with the sanctity of human life and commit to dignity and respect for all patients.” The humanitarian reputation that Dooley acquired seemed to indicate he abided by those principles.

Dooley graduated from medical school in 1953 and again joined the Navy. He completed his residency at Camp Pendleton, California, and Yokosuka, Japan. He then became a Navy doctor on USS Montague, an attack cargo ship, which sailed for Vietnam in 1954.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Following the May 1954 defeat of French forces by Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh independence movement, the Geneva Accords later that year formalized France’s exit from its former colony and provided for the temporary division of Vietnam at the 17th Parallel. That line divided Ho’s communist regime in North Vietnam from the noncommunist South Vietnam under Emperor Bao Dai, who was replaced by President Ngo Dinh Diem in October 1955.

The Geneva agreement mandated a nationwide election to unify the country by 1956. The election never took place, largely because the U.S. government feared that Ho’s communists would win and extend their rule throughout Vietnam.

Trouble in Vietnam

Under the agreement, Vietnamese who were residing in the north but didn’t want to live under a communist regime could move to South Vietnam. Critics claimed many of the evacuees were lured south by petty promises of “food, land and cash.” The U.S. Navy participated in the migration through Operation Passage to Freedom, an August 1954-May 1955 evacuation of an estimated 600,000-800,000 Vietnamese civilians and former French soldiers and their families. Dooley’s USS Montague was one of the evacuation ships.

Early in the operation, the young doctor was recognized as an excellent speaker and a persuasive writer. The Navy effectively made him a liaison to various government departments involved in the evacuation and, more importantly, to the media covering it. Dooley was featured in newspapers, magazines, movie newsreels and, notably, TV broadcasts, which were becoming an increasingly important news source for Americans. By the mid-1950s, a majority of American homes had a television.

In many ways, Dooley became the public face of the entire humanitarian operation to “rescue” Vietnamese from communism. Powerful Catholic publications, in particular, became a main avenue for his reporting and writing. These weekly and monthly publications reached millions of Catholics. Many of Dooley’s compelling articles, in abridged version, appeared in the Sunday Catholic Bulletin in churches nationwide. Dooley suddenly had a massive Catholic audience.

Dooley’s letters home to his mother, Agnes, were passed on to various newspapers. Many were printed in his hometown paper, the St. Louis Globe Democrat. He also made contacts with Reader’s Digest magazine and New York publishers.

In the late 1950s, Dooley revealingly stated that humanitarians in the modern world had to run their organizations like a business with “Madison Avenue, press relations, TV, radio.” Dooley added, “Of course you get condemned for being a publicity seeker.”

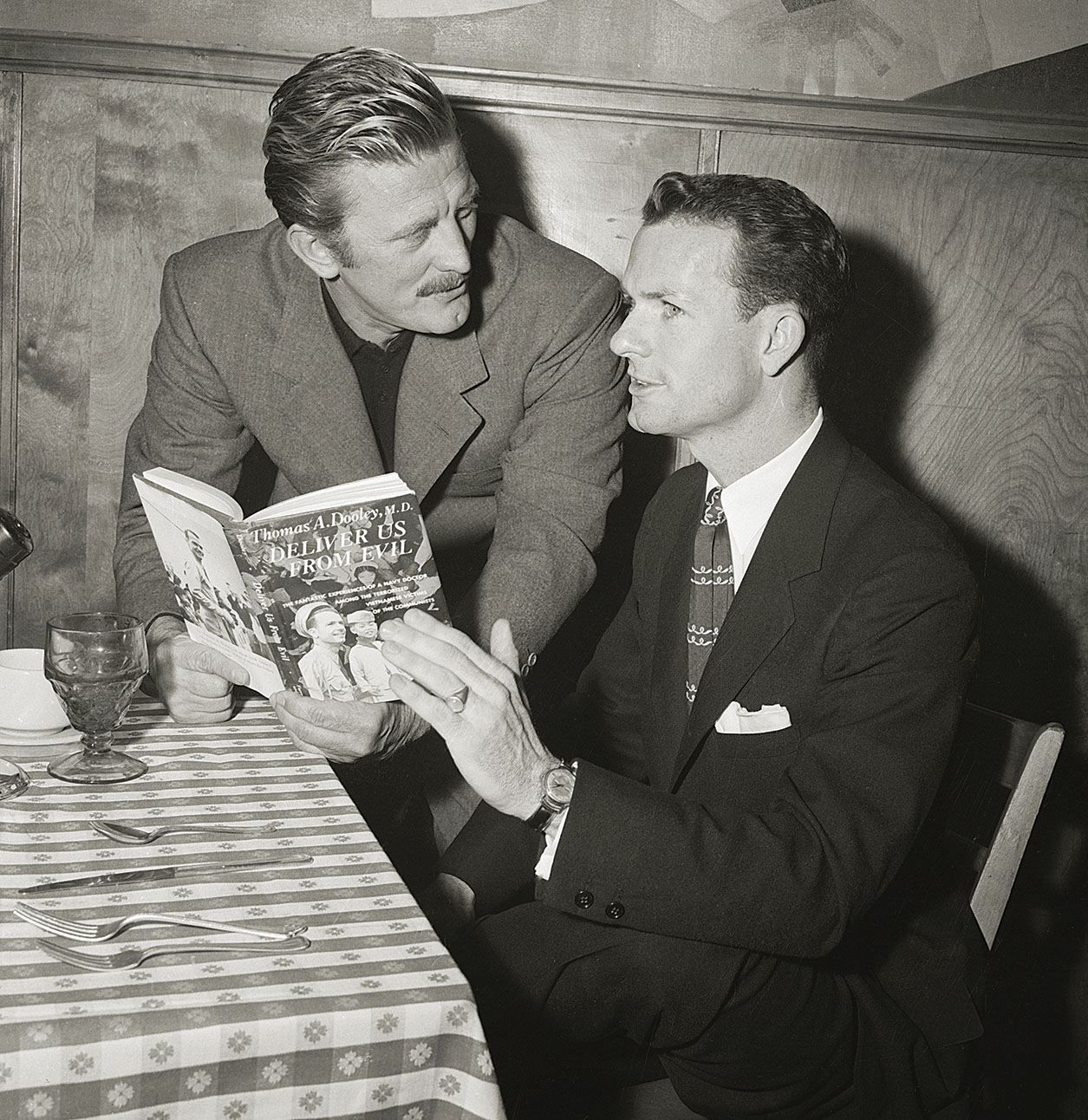

Becoming an Author

Dooley turned his experiences and views into a book, Deliver Us From Evil, published in January 1956. He was assisted by William Lederer, who with Eugene Burdick would become co-author of the best-selling 1958 novel The Ugly American. More significantly, Lederer served on the staff of the commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet 1951-57. He met Dooley during Operation Passage to Freedom, was impressed with the doctor and his anti-communist views and encouraged him to write the book. The Navy gave Dooley a leave of absence to work on it.

Deliver Us From Evil focused on Operation Passage to Freedom and Dooley’s central role in establishing hospitals and clinics. It also contained a dramatic catalogue of Viet Minh horrors that Dooley claimed to have witnessed or heard of. These graphic stories included one about a Catholic priest who had allegedly been hung up by his legs and another who supposedly had nails driven into his head in a Viet Minh version of the “Crown of Thorns.” Other passages claim that communist Vietnamese—Dooley called them “puppets” of Moscow—had disemboweled more than a thousand native women and pierced the ears of children with chopsticks to prevent them from hearing the word of Jesus.

Dooley’s book, which also included human-interest stories, glorified the author’s achievements. Fortunately for the Vietnamese, “our love and help were available,” Dooley wrote. He said the most important center in the refugee camp was its church, where the refugees thanked God “for having given them their freedom.”

Later, a multitude of witnesses debunked Dooley’s stories, asserting they had never seen any of the events he described. At least six U.S. Information Agency officials who had been in Vietnam at the same time as Dooley, as well as a Navy corpsman who worked with him, stated that his claims were false. In a 1991 interview with Los Angeles Times journalist Diana Shaw, Lederer stated:

“Those things [that Dooley reported] never happened. …I traveled all over the country and never saw anything like them.” Lederer also told Shaw he had not seen Dooley’s descriptions of the atrocities prior to the book’s publication.

Passages Removed

Recent research indicates some original passages were actually toned down or cut. One of Dooley’s drafts referencing the horrific acts that allegedly occurred against Catholics included an assertion that “there can be no concessions, no compromise” in the fight against communism, which isn’t in the book. On June 1, 1956, in a speech to the American Friends of Vietnam, an organization promoting U.S. aid to South Vietnam, Dooley described communism as “an evil, driving, malicious ogre.”

An abbreviated 27-page version of Dooley’s book appeared in Reader’s Digest, the largest-circulation American magazine of that time with 20 million readers. Deliver Us From Evil shot up on the best-selling list. The doctor became a global celebrity.

Forced to Conceal Sexuality

Dooley resigned from the Navy in March 1956. His official explanation was that he could be of more service as a civilian than he could be as a Navy doctor. Yet that was not the real reason.

An internal investigation by the Navy into Dooley’s private life had discovered homosexual activities, which were grounds for dishonorable discharge from all military services during that time. As Dooley’s fame grew, his sexuality became harder to conceal.

Dooley wrote two more widely read books, The Edge of Tomorrow, published in 1958, and The Night They Burned the Mountain in 1960. In each one, Dooley is shown with an Asian child on the front and back covers. All three of his books were printed in paperback editions to make them affordable to the widest possible audience of readers.

Americans eagerly embraced this man and his inspiring stories about confronting communism in Asia. He embodied the way Americans saw themselves during the Cold War, presented to them as an existential struggle of Communism vs. Freedom. The publicity campaign for Dooley’s book was designed not just to make the doctor a celebrity, but also to shape public opinion’s about Indochina and its position in the political battle against communism.

A strong influence in Dooley’s anti-communist proselytizing was the Roman Catholic Church, especially New York City’s Cardinal Francis Spellman. The cardinal was one of the most powerful Catholic leaders in the world, perhaps second only to Pope Pius XII. Spellman had met South Vietnam’s Diem, a devout Catholic, in 1950 and pushed for him to lead the South. With its heritage as a colony of Catholic-dominated France, Vietnam had an extremely large Catholic population, second only to Buddhism in the country.

Words from Dooley’s Deliver Us From Evil were incorporated into Sunday sermons at the Children’s Mass in Catholic churches. The book was required reading at some Catholic schools. Copies were sold after Mass. At times special collections were marked for Dooley’s Medical International Cooperation Organization, or MEDICO, founded to build and staff hospitals in Laos.

According to a 1959 Gallup poll, Dooley was the seventh “most admired person in the world.” Images of the doctor and his moving stories of Southeast Asia’s struggles against communism appeared in Life, Look and Time magazines. There was even a 10-page spread in Canada’s Maclean’s weekly magazine. When Americans turned on their televisions in 1959, Dooley seemed to be everywhere.

Rising As a Celebrity

On Nov. 18, 1959, while in Los Angeles, Dooley was a guest on “This Is Your Life,” hosted by Ralph Edwards. Edwards would surprise celebrities who were in town and take them into his studio, where they would hear offstage voices from their past. After a reaction from the guest, the people offstage would come out front—in Dooley’s appearance, this included people from his time in Vietnam and Laos.

“The What’s My Line” show of Nov. 22, 1959, hosted by John Daly, featured the regular panel of Dorothy Kilgallen, Arlene Francis and Bennett Cerf, joined for this episode by acclaimed author James A. Michener. With the panel securely blindfolded to prevent visual recognition, Dooley silently “signed in” on a chalkboard to loud audience applause. Each panel member was allowed to ask questions to elicit “yes” or “no” answers from the guest, who often responded with a disguised voice to prevent recognition.

Francis eventually guessed correctly, and the other panel members, removing their masks, were excited. Daly called Dooley’s work in Laos and Vietnam “a story the American people have come progressively to know more about” and made a reference to Viet Minh aggression. He then presented Dooley with a $5,000 check from the Damon Runyon cancer fund to support MEDICO.

Dooley continued to flood the airwaves. He appeared on Today with Dave Garroway and received a check for $10,000 to assist his organization. He was also Jack Parr’s guest on The Tonight Show. Arthur Godfrey featured Dooley on his popular TV and radio shows.

Dooley raised funds in Hollywood and attended numerous banquets across the country, several with Spellman. There was talk of a movie about him starring Kirk Douglas. Dooley had his own weekly radio show and wrote weekly newspaper columns. During the few years before his death, Dooley traveled more than 400,000 miles.

The doctor was such a well-known celebrity that he agreed to televise his own surgery for melanoma cancer for a CBS documentary, “Biography of a Cancer,” broadcast on April 21, 1960. The program included a long interview conducted by journalist Howard K. Smith. Dooley died from the cancer at Sloan Kettering Hospital in New York on Jan. 18, 1961—one day after his 34th birthday.

The Undoing of His Image

Tributes poured in from outgoing President Dwight D. Eisenhower and even the pope. Thousands turned out for Dooley’s funeral in St. Louis. In a White House ceremony on June 7, 1962, Kennedy presented Agnes Dooley with her son’s Gold Medal authorized by Congress. A year after Dooley’s death, a documentary was made with footage of the doctor’s work and his clinics. That film, “The Other War in Southeast Asia,” narrated by actor Gene Kelly, was shown at fundraisers such as church functions and civic events.

Over time, Dooley’s carefully crafted image began to fall apart. In 1975, the Rev. Maynard Kegler, one of Dooley’s religious contacts in the 1958-61 period, began doing research to promote the doctor’s canonization to sainthood. Kegler came across 500 pages of unclassified documents in CIA files indicating that Dooley had helped the agency.

For example, Dooley provided the CIA with information about enemy troop movements and local attitudes toward both the communists and the Americans. Kegler defended Dooley’s ties to CIA officials, nonetheless.

“He gave them information out of patriotism, love of country and all that the United States stood for in 1958,” Kegler said in a 1979 interview with People magazine.

Some evidence indicates that Dooley allowed U.S. troops out of uniform in Laos to stay at his clinics disguised as medical staff.

An investigative piece on Dooley by Shaw of the Los Angeles Times appeared Dec.15, 1991, with this long headline: “The Temptation of Tom Dooley: He was the heroic jungle doctor of Indochina in the 1950s. But he had a secret, and to protect it, he helped launch the first disinformation campaign of the Vietnam War.”

Shaw noted that 50 civil servants sent a letter to the publisher of Deliver Us From Evil to protest Dooley’s account of his work in Southeast Asia.

The letter, according to Shaw’s article, stated that Dooley “exaggerated his role in the refugee camps at the expense of the people who were working with him, many of whom did just as much, if not more, than he did.” Shaw wrote that the editor of Dooley’s book “had an idea that the book wasn’t, strictly speaking, true.” But the editor, in his defense, told her that “it had the essence of truth,” and during the Cold War “that was just as good.”

Sainthood Movement Evaporates

Dooley undisputedly had a flowery way with words that made his writing persuasive, as Shaw illustrates with this anecdote from the doctor’s Navy days: “While the ‘situation reports’ commonly filed by medical commanders were blunt and straightforward accounts of the day’s work, Dooley’s were eloquent. The brass recognized that his chronicles, enlivening the dry details with dramatic descriptions and impassioned patriotic commentary, could boost morale. They sent them throughout the fleet so that everyone, from corpsmen to vice admirals, could read them.”

The movement to make Dooley a Catholic saint has evaporated. The reason may have had more to do with the Catholic Church’s position on homosexuality than with Dooley’s CIA ties.

Following his cancer diagnosis, Dooley lamented in a conversation with Dr. Vincent J. Fontana, director of the New York Foundling Hospital, that “nobody loves me,” according to Shaw’s article.

Fontana pointed out to Dooley that the doctor received letters from across the globe, showing that many people loved him. But Dooley replied to Fontana, as Shaw relays the conversation, that “if they knew him, they would find him loathsome.” Fontana told Shaw that Dooley “gave in to the stigma” surrounding his homosexuality.

In Dr. America: The Lives of Thomas A. Dooley, published in 1997, author James T. Fisher explored the complex and seemingly contradictory characteristics of Dooley’s life.

Reviewing the book for The Washington Post, psychiatrist Robert Coles summed up Fisher’s take on Dooley this way: “a vain, arrogant, self-promoting, ambitious, manipulative storyteller who knew how to exaggerate, tell small fibs and big lies; but also a sensitive, generous, idealistic and compassionate doctor who put himself on the line, under difficult circumstances for the most needy of people.” V

Jim Trautman, a former Marine, wrote The Pan American Clippers—The Golden Age of Flying Boats, a book first published in 2007 and updated in 2019. He lives in Kitchener, Ontario.

This article appeared in the October 2020 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook:

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.