Joann Puffer had a year of teaching and a year as an American Red Cross Donut Dolly in Korea under her belt when she volunteered to go to Vietnam in 1966. Looking for excitement, she found it visiting troops across the war zone, from the Central Highlands to the Mekong Delta, from the South China Sea to the Cambodian border. While Puffer, like the other Donut Dollies, was often tasked with setting up recreation centers and programs at secure bases, she was also among the first civilian women officially sent into combat zones.

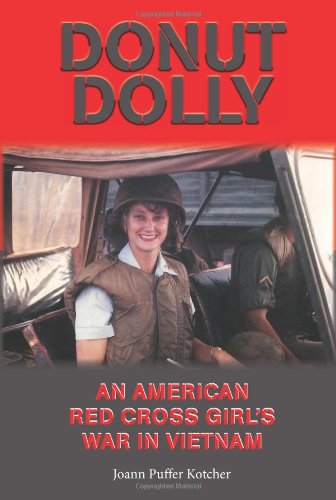

Joann Puffer Kotcher’s memoir, Donut Dolly: An American Red Cross Girl’s War in Vietnam, excerpted here, offers a unique perspective from one of some 600 young women who served, often in harm’s way, to bring a touch of home to the Americans in Vietnam.

The American authorities in Vietnam confined most women to relatively safe, rear areas. However, commanders allowed the Red Cross girls to go visit the men everywhere, even the foxholes. Commanders sometimes asked us to take risks because they thought our visits meant so much to their men—as was the case for me on Thanksgiving Day, 1966.

Dee Walton and I planned to visit the 1st Infantry Division’s 2nd Battalion, 2nd Infantry Regiment in their field position at Phu Loi. As soon as we arrived, however, our escort, Captain Jerald D. Fuhriman, told us that we would have to wait. “B and C companies are in a firefight, and everyone else is in an awards ceremony,” he told us. “We can’t see units in the field or in base camp until after the ceremony.”

We knew that we could not present a recreation program on this visit, but we hoped to serve Thanksgiving dinner at as many places as possible. It would give the men a chance to talk to an American girl, perhaps for the only time during their combat tour.

A smattering of personnel moved among headquarters buildings, and Dee and I joined half a dozen men gathered around a field radio on a jeep. They were listening to the conversations going on among the elements engaged in the fighting that was making us wait. The men brought us up to date: “A unit of our infantry has engaged a group of Viet Cong at one end of the valley. The VC broke off and fled down the valley. Our scout helicopters spotted them, and told the commander their strength, position and movement.”

Another soldier continued: “The commander directed another infantry unit to intercept the Viet Cong. He ordered the first unit to withdraw, but to watch out for the VC doubling back and ambushing their withdrawal.”

Over the radio, Dee and I could hear the commander give the order: “Pull out bag and baggage and all your wounded. Make sure there’s somebody covering your ass!” He called for artillery and for a dustoff for the wounded. The soldiers listening to the radio cheered and rooted for each unit, as if they were listening to a ball game. Their friends were out there. One shouted, “Yes, get the artillery in there, level that house, get that sniper!”

“Why aren’t they using the tanks?” someone wondered. “They’ve got four tanks out there.”

“Here comes the dustoff. I see it, over there,” said one of the soldiers, pointing off in the distance. We spotted the medevac in the sky above the treetops, a big red cross on its side. I watched it creep as it searched for the colored smoke that revealed where to pick up the wounded. The enemy, no doubt, had plenty of time to take aim at the helicopter. It dove into the trees. “Those people will go anywhere,” someone said.“They’re going to draw a lot of fire on that one.” Everyone nodded, their eyes wide. Finally, on the radio, we heard the chopper confirm liftoff with the last wounded soldier on board. Dee and I were relieved—a Hollywood happy ending.

At the awards ceremony everyone made way for us so we could move to the front. Rows and rows of men covered the field.

“This is big, ” Dee said.

“How many men do you think are out there?” I asked.

A lieutenant who stood nearby replied nonchalantly, “There are about 2,000 men on the field in review today.” All during the ceremony, artillery continued to boom and whistle over our heads, in support of the fight we had been listening to over the radio.

The commanders presented the last medals, and the ceremony ended. Anxious to visit with the men, we hurried back to the officers club, where the cooks had prepared to serve us ahead of everyone else. Dee and I ate our Thanksgiving meal as fast as we could, before a 15-minute church service in an outdoor chapel, conducted by the chaplain, Captain Tom Carter.

Chaplain Carter’s sermon was titled “Abundant Life,” from John 10: 7–21: “I came that they may have life.” Carter asked for the troops to share what they were thankful for, even in the midst of war. “God gives not just enough life to keep going, not just enough courage, but overflowing and abundant,” he said. “On this day of Thanksgiving, my prayer is that you will seek the abundant life offered by God and share your thanks with those around you.” After the service, we helped the cooks serve dinner for base camp. We had just finished when Captain Fuhriman came to us with word that the fight had ended, and the area was now secure. We could now go visit the troops, the ones we had listened to over the radio. We left in two jeeps escorted by the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Jack L. Conn, Sgt. Maj. Harry Sanders and Captain Fuhriman.

When we arrived, the Company A commander, Captain Francis J. Thompson, gave us unit patches and made us honorary members of 2-2 Infantry. The Company A cooks had just started to serve dinner and we stepped in to help. These men had not taken part in the action, and they were clean and pressed for the occasion, right down to creases in their fatigue trousers and on their sleeves. We greeted each man with a smile: “Hello. Happy Thanksgiving. Would you like some fruit salad?”

“Same to you. Yes, thank you, Ma’am,” the men would reply.

Sometimes we could make a joke. “There’s no room on your plate,” I’d say to a soldier. “Shall I squeeze it in next to the cranberry sauce?”

“Yes, Ma’am. That will be fine,” he’d reply, eyes wide at the heap of food he carried. Soon we’d hear a burst of laughter from the end of the line where Dee served the pumpkin pie. Each soldier was served as much as he could eat. I remember a pancake supper we served at Dong Ba Thin, at which 75 soldiers ate enough pancakes for 150 men, after they had eaten their supper. When we finished serving, we walked around and talked to the soldiers as they sat in groups and enjoyed the food, picnic style.

Next, we served the dinner at B Company. These men had just returned from the fight with the Viet Cong and looked as if they had been crawling around in mud. Most of them wore no name tags, patches or rank.

It struck me that everywhere we went that day, the cooks had just begun to serve dinner. I was sure the cooks had orders to hold the meal until we arrived. Dee and I helped serve again, and afterward I joined a group of soldiers relaxing on a circle of logs under some trees. A sergeant arrived to escort me on a tour of the camp. Instead of a rifle, he carried a machete. It had to be a trophy. It must have belonged to someone in his unit, maybe even to him. I knew he expected me to notice it. “That’s quite a machete you have there,” I said.

“Yes,” he said, his chest swelling. “It’s from the fighting this morning. Let me show you our defenses.” We walked almost all the way to the perimeter. Suddenly, as I was admiring the bunkers and other fortifications, we heard a burst of small-arms fire, then another and another. “Get down!”the sergeant yelled. He shoved me into a bunker and ran, calling back over his shoulder, “I have to get back to my unit.” I skinned my elbow when I landed.

The Viet Cong were attacking Company A. I could see and hear men as they dashed about, snatching up their weapons and steel helmets. “Ammo over here!” they yelled. “Ammo! Ammo!”

I heard one holler,“Two miles away!” They jumped into trucks and roared out of sight. Then, all the men were gone, the perimeter was empty—and I was alone. I crouched down as far as I could in the small bunker and froze like a cornered rabbit in the stifling heat. I remembered how the division operations officer at An Khe had told us how scorpions had stung two men when they dove into bunkers. At any moment, I expected a VC in black pajamas and a cone-shaped hat to thrust a Soviet AK-47 in my face and say, “You come with me.” I remembered what Gerald Burns, of Military Intelligence, said when I asked him if the VC took prisoners. “Sometimes they take prisoners,” he answered, “but usually they do not. They have no facilities for holding prisoners.”

I didn’t dare look out of the bunker, because I knew if I could see the VC, they could see me. It felt like a long time as the fight grew louder and closer. I wasn’t panicked; I wasn’t even really scared. I had dived into bunkers so many times that it was part of the routine, but I felt lonely. I noticed when I first arrived in Vietnam how those around me would give me courage. Even one other person in the bunker with me would have made a difference. Finally, I heard a voice calling softly, “Joann, Joann, where are you?” Relief flooded over me.

I called back, “Over here.” I hadn’t heard the soldier approach. He moved without a sound, like a ghost.

“Follow me, run!” he said. “Keep down, over this way!” His uniform was rumpled and stained with dirt and sweat. He wore a sergeant’s rank on his sleeve, three chevrons—one corner hung loose. He carried an M-16 in his right hand, and his self-assured manner inspired confidence. He led me at a run, away from the sound of the guns. Even when he ran, he moved like a ghost. We burst into the field position and he pushed me into another, much bigger bunker and ordered, “Keep down!”

Dee was there, too, sitting on the dry, clean, scorpion-free dirt floor. “I was on the other perimeter when the fighting broke out,” she told me, looking relieved. “Everyone was frantic when your escort came back without you.”

I looked out through the doorway of the bunker. A handful of men lounged there as though they didn’t have a job. A dozen others surrounded us behind sandbag walls. I heard a scrape and click. Several soldiers inserted clips into their rifles, unhurried and long practiced. With weapons loaded and ready, they watched and listened to the rustle of trees and the fight nearby.

Two men gave us their helmets. “Put these on if mortar rounds start coming in,” they said.

A few minutes later, the jobless men burst into action. They snatched up helmets and ran, yelling, “Fire mission!” Within minutes, mortars started going out from right next to us. The VC must have been headed our way and were less than a mile out. The frantic mortar crews fired nonstop for five or 10 minutes. Dee and I couldn’t see anything and we couldn’t hear anything over the sound of the guns: boom, swish, boom, swish. All we could do was get down and stay down.

Two men gave us their helmets. “Put these on if mortar rounds start coming in,” they said.

When the booming of the mortars finally stopped, a sergeant came to the doorway. Through my ringing ears, I heard him say, “You can come out now.”

Dee and I had planned to visit Charlie Company next. Captain Fuhriman broke the news: “This is the company that has seen the most action during the day, as well as during the past week. The fighting that just took place was about a quarter of a mile off the road between here and C Company. It won’t be safe for us to go through there. Even if we could, we wouldn’t be able to get out and back along the roads before dark.”

Disappointed, Dee and I loaded up in separate jeeps, spaced far apart for safety, and headed toward 1st Infantry Division Headquarters at Di An. Along the way, we met Colonel Conn, who was returning from the battle. He stopped our jeeps and spoke to our escort several yards away. I watched the colonel, who was seated next to his driver, talking with Captain Fuhriman. His helmet moved from side to side and jerked up and down. He said something to his radioman in the back seat of the jeep, who then made a call. The colonel spoke again to our escort, gestured and pointed down the dirt road, back in the direction he had come.

Captain Fuhriman pulled his jeep over next to Dee’s and then to mine. He looked worried. “The colonel still wants you to visit C Company,” he said. “He has ordered his four escort jeeps armed with machine guns to turn around. They will join our three, and together we will take you to C Company.” The colonel set a fast pace, our best defense as we passed through woods. Tense, I watched everywhere for shadows.

At Company C, Dee and I joined the cooks in the mess line. This time I served the pie, and she gave out the fruit salad. Adrenalin and dirt still clung to the infantrymen. Morale seemed to soar as we greeted and joked with each one. The noise level in the mess line climbed, and nonstop laughter pierced the quiet jungle. With the battle won and everyone safe, the plates heaped up with hot Thanksgiving food shouted, “Celebration!” The reminder of home that Dee and I represented added a spark, like fireworks. I saw Colonel Conn, for a moment, way in the back. He looked over the scene, nodded slightly to himself and disappeared.

The dinner served, Dee and I split up and walked around, joking and laughing with everyone. We came upon some 20 officers clumped together at one end of the compound sharing a bottle of champagne in paper cups. They divided the last of it between Dee and me as another officer arrived. Several people poured a little of their champagne into a cup for him. The officers, for their safety, wore no name tags, few wore rank and no one saluted. They communicated mostly with glances, not speech. I greeted Chaplain Carter, who had arrived ahead of us at each stop all day and had preached his sermon to each company, 265 men in all. “We have a lot of admiration for him,” a captain remarked. “He makes a big effort to reach the men in the field.” The officers raised their cups in salute.

A fresh-faced lieutenant complimented us, “Your being here has raised morale 90 percent.” A chorus muttered agreement and nodded. I laughed at the exaggeration.

“If Charlie tries to attack tonight he’s in for real trouble,” someone said.

The group glanced agreement at each other. “Yes, he’s in for trouble,” several repeated.

Just then a helicopter appeared in the sky, carrying the 1st Infantry Division commander, Maj. Gen. William E. DePuy. His chopper landed outside the camp’s earthwork berm, a few yards from where we stood. Then the assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. James J. Hollingsworth’s chopper settled down beside General DePuy’s. A third chopper landed as well.

Suddenly anxious, some of the officers were glancing at a clump of palm trees about 200 yards away across the gray rice paddies. A round-faced lieutenant asked the officer standing beside him, “How long can all those choppers sit there, a nice juicy target, before the VC open up again?”

Someone barked an answer: “Get down! Get down!” Everyone dropped. Champagne and cups flew.

I hugged the ground. “What is it?” I asked.

“A sniper,”the lieutenant answered. “Probably from that clump of palm trees.” I felt bare. I looked around.

We all strained to listen for more shots. Silence. Men ran, keeping low, and shouted. An officer a few feet away explained, “They’ll form up a squad to go after the sniper.” He stood up and ran, bent over. The sniper had probably already hidden his weapon in the brush. Perhaps it was a moonlighting local farmer, who by now was trotting back across the rice paddies to his village for supper. Tomorrow he might be selling souvenirs to the soldiers he just shot at. But to be on the safe side, everyone would assume the worst until the danger was past. It looked like chaos, but it really wasn’t. Every runner knew his destination and his assignment. The helicopters, which had not shut down their engines, took off like startled dragonflies when the shooting started. The generals, all of us, were stranded. If this was an attack, we had cast our futures with those soldiers.

Our frantic escort officer yelled to me: “Get in a hole! Run! Keep down!” I raced after him. He threaded me through the crowd, ordering,“Get in here and stay down!” Then he vanished.

I couldn’t see which shelter he indicated. I asked, “Where?”

I heard Dee say, “In here.” She’d beaten me to safety, again. I crouched there and concentrated on staying down. A sergeant appeared, drew his .45 and knelt in the doorway. A sniper attack, the enemy so close, brought a rush, but it didn’t last long. Reality crowded it out. Getting shot at could get you seriously dead.

After a few minutes an officer stuck his head into the bunker. “You can come out,” he said. “No more rounds have come in. It was just a sniper.” The sergeant in the doorway holstered his .45 and disappeared. The helicopters returned.

I found Captain Fuhriman. “Thank you for taking us to see so many men, and especially for getting us to Charlie Company,” I told him.

His shoulders drooped. “Yes, but I’ll feel a lot better when you get on that chopper and get out of here,”he said. One of the helicopters was waiting for us, and Dee and I ran to climb aboard. As we rose into the sky, I looked out over the company’s position to the clump of palm trees. Beyond it and all around were miles of dry rice paddies. I strained my eyes in the dusk. Could I see, at the far end, a farmer trotting toward the village?

I didn’t learn until years later that Captain Francis Thompson, the Company A commander who gave us unit patches at the beginning of the day, was killed in action two months later, on January 24, 1967, in a firefight near Tay Ninh.

Sergeant Robert Fulps, the rifle squad leader, 3rd Platoon, Company C, 2-2, who was talking with General Depuy the moment the sniper fire erupted and then ushered Dee and me into the bunker, later told me: “It is entirely possible that your light-colored uniform would have made a very distinguishable target. If that was the case, God surely had his hand on you that day.”

Indeed, that was one Thanksgiving I clearly had much to be thankful for.

Donut Dolly: An American Red Cross Girl’s War in Vietnam

by Joann Puffer Kotcher

If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.