The Vought F7U Cutlass originated with a 1945 Navy fighter competition for a carrier-based fighter able to fly at 600 mph and 40,000 feet. Vought Aircraft was known for unusual designs, and the futuristic-looking V-346A proposal was certainly that. It would be the Navy’s first swept-wing fighter and America’s first tailless fighter to go into production. The proposal resulted in a contract for three XF7U-1 prototypes.

The prototypes of the bat-like fighter first flew in 1948 and the initial test flights were encouraging. Powered by two Westinghouse J-34 turbojets, the airplane promised speed and exceptional maneuverability. But a litany of woes soon dogged the program.

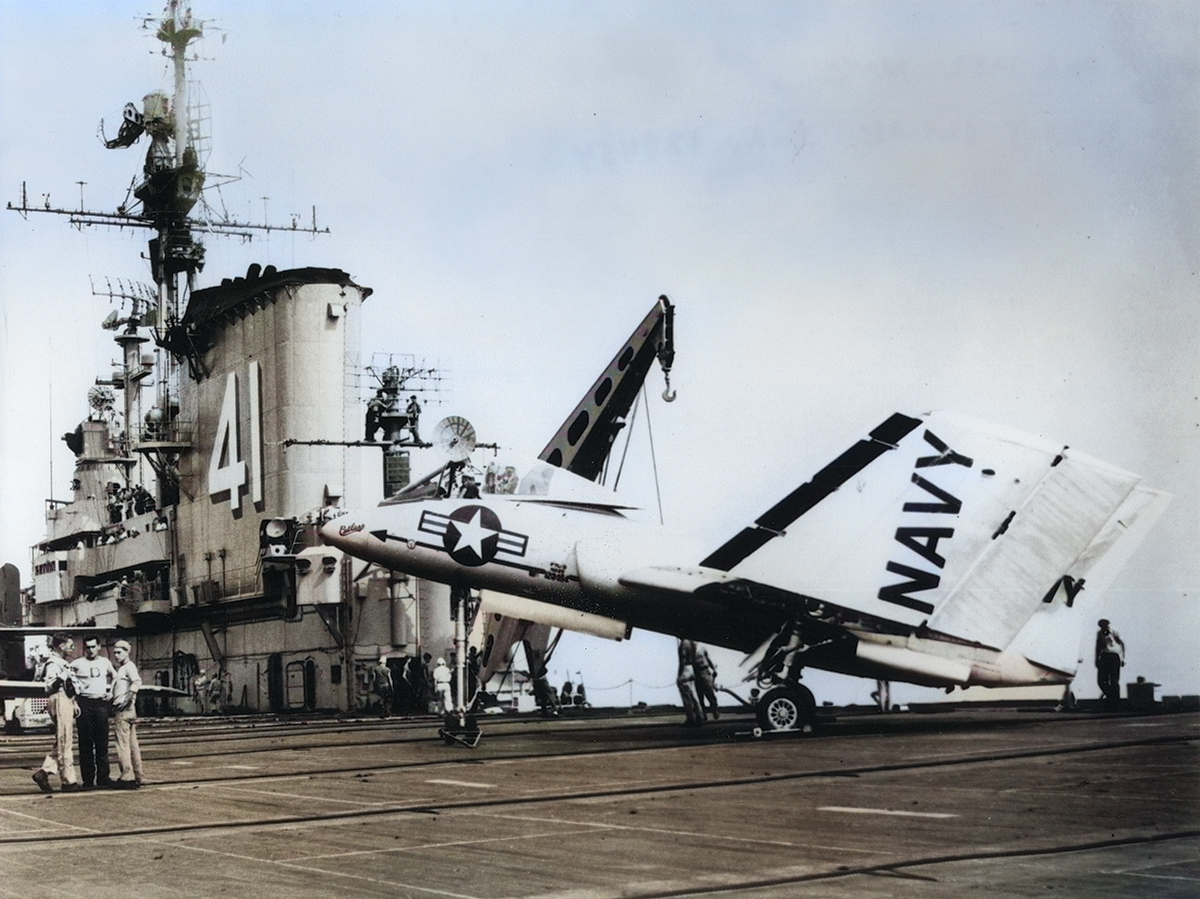

After nearly a decade of development, in 1954 the Navy began equipping 13 squadrons with the F7U-3 version of the carrier-based jet. But the “Gutless Cutlass” proved to be accident-prone and plagued by gremlins. Even with more powerful Westinghouse J-46 engines the big twinjet proved woefully underpowered, especially during demanding carrier approaches. It acquired a bad reputation and the Navy had withdrawn it from frontline service by late 1957.

Vought manufactured 307 F7Us, with production ending in 1955. Fewer than 10 of those airframes remain today and one, serial number 129565, is currently nearing the end of a restoration at San Diego’s USS Midway Museum. The Navy accepted this particular jet in 1953 and it last served with attack squadron VA-212 aboard the carrier USS Bon Homme Richard before being retired in April 1957 with only 273 hours on the airframe. The Cutlass ended up as a gate guard at Naval Air Station Olathe, Kansas, for several years. The Midway Museum retrieved it from a Vought retiree group in Texas that had been doing restoration work.

Like many baby boomer kids, I fueled my fascination with aviation with model airplanes and one my favorites was the F7U with its bulbous canopy and spindly nose gear. So, I made plans to look in on the Cutlass restoration project.

Entering Midway’s restoration hangar in the spring of 2021, I was immediately impressed by the project’s scale. Cutlass parts were scattered throughout the hangar. The airplane’s large, broad wings with tall vertical fins were detached and they and the 40-foot-long fuselage crowded one side of the hangar. The nine-foot nose gear strut—one of the Cutlass’s problematic design features—landing gear doors, dive brakes and miscellaneous bits and pieces occupied the other side. The sounds of rivet guns and grinders echoed through the hangar as restoration volunteers worked on the jet.

Midway Air Wing Project Manager Royce Moke knew he had a big job ahead of him getting the Cutlass restored for display aboard the aircraft carrier museum. When asked about the biggest challenge, Moke didn’t hesitate. “Getting the wings fitted back onto the fuselage,” he said. To complicate matters, Midway’s restoration team didn’t take the airplane apart. It arrived in pieces from the previous restoration effort. Working without drawings or a maintenance manual, Moke had to figure out how to hoist the heavy wings and maneuver them into a position to fit the fuselage’s wing-mounting lugs. He was later able to enlist the help of four sailors from VRM-50, a Navy Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey tiltrotor squadron. They volunteered their free time and used a forklift to help the restoration team get the wings on in less than half a day.

Then there were unusual elements with which the restoration crew had to deal. For example, the team refurbished the wooden skids that the Cutlass had on the fin stubs beneath the wings, which sometimes hit the carrier’s deck during landings. The replaceable hardwood skids prevented damage to the aluminum. Needing to minimize airframe weight, Vought had patented a special fabrication process for light but rigid airframe skins called Metalite. A sandwich of balsa wood with lightweight aluminum skins glued on each side, Metalite was used around the cockpit and on the wings. Many of the balsa cores had deteriorated over the years of outdoor storage. Because the airplane would not return to flight, the team kept the Metalite panels around the cockpit area (with their compound curves) in place. For the wing panels, they replaced the Metalite with aluminum skins of roughly the same thickness and used metal spacers to make up for any differences.

Luckily for the restoration effort, San Diego is a Navy town with many motivated and skilled aircraft technicians. Among them is Phil Lavullis, an aircraft sheet metal worker with 30 years’ experience repairing damaged aircraft around the world. “I always liked working on things with my hands and restoring something that’s rare and among the last of its kind is motivating,” he told me. But Lavullis found the Cutlass to be especially challenging: “There’s nothing to go on, no blueprints or another Cutlass nearby that we can take measurements from.”

Despite the airplane’s bad reputation, former naval aviator and long-time Midway Museum member Dick Cavicke remains a staunch defender of the jet. As a young Navy ensign in late 1954, he was assigned straight out of naval flight training to fly F7Us with VF-124. “The Cutlass was more exotic looking than anything I had ever seen, and I was anxious to fly it,” he recalls. He acquired nearly 400 hours in F7U-3s with two squadrons based at California’s NAS Miramar, making him one of the airplane’s most experienced pilots.

As of this writing, the Cutlass has been reassembled and needs only its livery. “Our Cutlass will be displayed in the silver metal scheme of the plane used in the August 1952 carrier qualification tests aboard the USS Midway,” said museum curator David Hanson. And he added, “We want a Cutlass because it’s an interesting aircraft and not many are on public display in this part of the U.S.”

The projected completion date for this rare carrier fighter is late 2022. “Painted on one side of the cockpit will be the name of former Cutlass pilot, and the airplane’s sponsor, Bill Montague,” said Hanson. “And on the other side, Wally Schirra’s name, the friend and mentor who taught Montague to fly the jet.” Schirra went on to become one of the original Mercury 7 astronauts and he also flew Gemini and Apollo missions, but I think it’s a safe bet that he never forgot what it was like to fly the Cutlass.