U.S. Marine tanks and ARVN troops unload on a North Vietnamese battalion.

One of the most devastating defeats inflicted upon the North Vietnamese Army by U. S. Marines and their South Vietnamese allies occurred on Aug. 15, 1968, in the coastal sand dunes northeast of Gio Linh and on the south bank of the Ben Hai River separating North and South Vietnam.

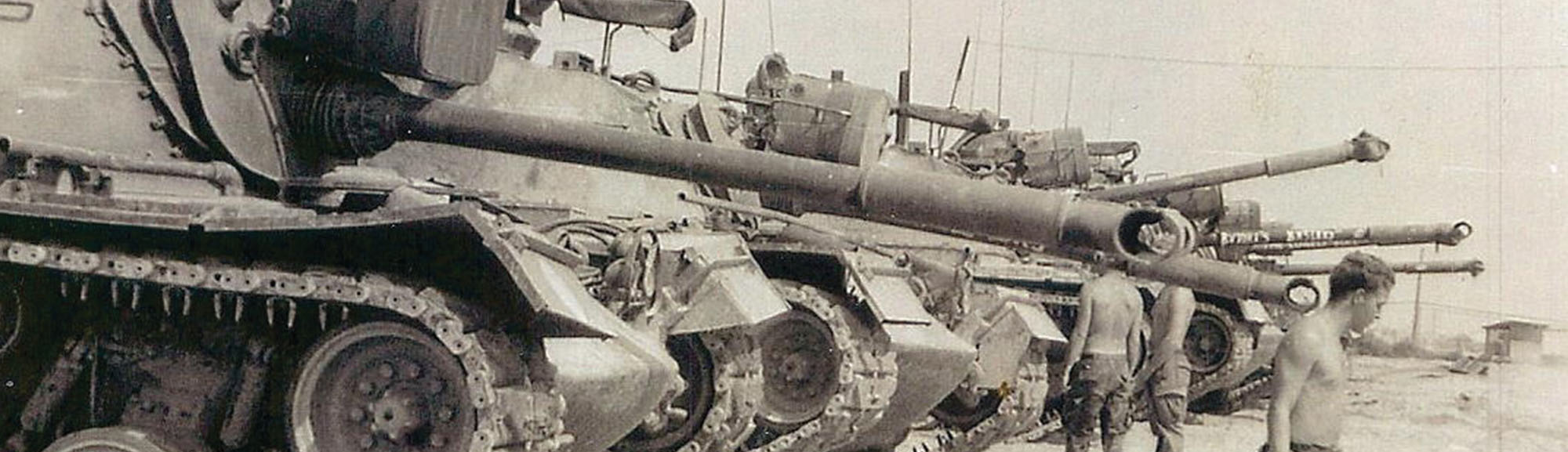

Ten Marine M-48A3 Patton tanks from 3rd Tank Battalion, 3rd Marine Division, surprised a North Vietnamese battalion at dawn. The tankers, with elements of the 2nd Regiment, Army of the Republic of Vietnam, opened fire and attacked, overrunning the NVA and destroying a frogman training facility at the Ben Hai River.

The Marines, who described the day’s action as a “turkey shoot,” also destroyed several trucks and sank two enemy boats in the river. There were no Marine casualties. But that remarkably successful joint Marine Corps–ARVN operation, called Lam Son 250 by the ARVN, was largely ignored by American press, for reasons that aren’t clear. Perhaps it was because the battle was primarily an ARVN operation.

In July 1954, the Big Four (United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union and France), along with representatives of the People’s Republic of China, met in Geneva to finally resolve the Korean War stalemate, but the focus shifted to Indochina after the French army’s disaster at Dien Bien Phu in May brought an end to France’s colonial rule. The Geneva Accords, issued on July 21, called for temporarily dividing Vietnam at the 17th parallel (referred to as a “provisional military demarcation line”), with a Demilitarized Zone as a buffer. American and South Vietnamese troops would fight the North Vietnamese in the strategically important region throughout the war.

The DMZ generally followed the broad, winding Ben Hai River west from its mouth at the South China Sea for 30 miles until the river’s source in the mountains and then straight to the Laotian border. Where the Ben Hai empties into the sea is a barren expanse of sand dunes and occasional swamps. Inland a dozen miles from the coast, the lowland terrain becomes increasingly verdant and alive with rice fields, orchards and occasional hamlets bordering the river.

The DMZ eventually evolved into anything but “demilitarized” as the North Vietnamese moved their forces in, using both sides of the Ben Hai River as staging areas for attacks and infiltration routes into South Vietnam. The South Vietnamese and their American allies observed the rules of the Geneva agreement for many years and kept their ground forces out of the DMZ, but in May 1966, after the NVA 324B Division attacked two ARVN outposts just below the zone at Con Thien and Gio Linh, that policy changed. Four Marine battalions and a sizable South Vietnamese infantry unit invaded the southern part of the DMZ for the first time when the Marines’ Operation Hastings was coordinated with the ARVN’s Operation Lam Son 289.

In May 1967, after a massive NVA attack that nearly overran the Marine firebase at Con Thien, the Marines launched Operation Hickory to clear the North Vietnamese out of the southern DMZ. The operation was definitely a setback for the NVA, but only temporarily.

In early July 1968, the entire 9th Marine Regiment, accompanied by three platoons from 3rd Tank Battalion, invaded the DMZ on Operation Thor. Once again, a highly successful operation supposedly cleared the North Vietnamese out of the southern half of the DMZ “permanently”…but again, it was not for long.

In August 1968, after a week of bloody clashes with the 1st Battalion, 138th NVA Regiment, around the firebase at Gio Linh, the commander of the 2nd ARVN Regiment, Lt. Col. Vu Van Giai, asked permission to launch another attack into the southern half of the DMZ. Final approval was granted by Marine Maj. Gen. Ray Davis when intelligence reports indicated that the NVA was building up its forces in the zone for an autumn offensive.

After several B-52 bombing runs that blasted known and suspected enemy locations in the DMZ, a diversionary attack was launched before dawn on August 15 by elements of the Marines’ Amphibian Tractor Battalion—15 tracked landing vehicles (Amtracs) and two tanks. Rolling noisily out of Marine outpost C-4, the Amtracs and tanks halted about a half-mile south of the DMZ’s southern boundary, then reversed course back to C-4. This diversion set the stage for the joint Marine-ARVN attack into the DMZ later that morning.

Five tanks from 1st Platoon of Alpha Company, 3rd Tank Battalion, were led by 2nd Lt. Frank Blakemore, who had been with the platoon for only a month. Captain R.J. Patterson, the new commanding officer of Alpha Company, was the overall detachment leader and rode aboard tank A-15. That tank (with its name, “Stink-Finger,” painted on the main gun barrel) was normally commanded by Corporal Virgil Melton Jr., a lanky,combat-wise Marine from Canton, Texas.

The lieutenant told Melton, “The captain will have to ride on your tank, so you’ll have to move over into the loader’s spot.” Melton remembers that the move gave him few anxious moments. “I’d never seen the new CO, so I could only hope that this captain had his act together,” he said.

The other five Marine tanks participating in the operation, based at Camp Carroll, were the 3rd Platoon of Bravo Company (also in the 3rd Tank Battalion), led by Gunnery Sgt. Kent Baldwin.

That detachment of 10 “iron monsters” was a force to be reckoned with. All of its M48A3s were the latest model in the Patton medium tank series, boasting several improvements over the Army’s M48A2—probably the first time in modern military history that the Marine Corps had better equipment than the Army. The major improvement in the A3 series was replacing the gasoline engine with a Continental V-12 supercharged 750 horsepower diesel engine, which greatly reduced the risk of fire. Other enhancements were a 360-degree vision ring on the tank commander’s cupola and a Xenon searchlight with infrared capability for night operations.

The M48A3’s armament included a 90mm (3.54-inch) main gun, a .30-caliber co-axially mounted machine gun and a .50-caliber machine gun in the commander’s cupola. A fully loaded tank weighed 52 tons and had a top speed of 30 mph.

The four-man crew consisted of a tank commander, a gunner, a loader and a driver. The gunner had a ballistic computer that could automatically set the main gun tube’s elevation to hit a target by direct fire up to 3,000 meters distant. Hitting anything farther away would necessitate employing “Kentucky windage”—aiming without using the barrel sights and instead estimating the elevation and wind with educated guessing, as shooters did with the Kentucky long rifle of American pioneers in the 1700s.

At 4 a.m. on August 15, the Marine-ARVN detachment moved north from its overnight location east of Gio Linh. In addition to the 10 Marine tanks was a tank retriever (C-43) commanded by Captain Dan McQueary, commanding officer of the 3rd Tank Battalion, Headquarters and Supply Company. Five ARVN infantrymen rode atop each tank. The rest of the force was carried in accompanying armored personnel carriers, or APCs, from the ARVN 11th Armored Cavalry.

Moving single file to minimize exposure to mine damage, the allied attacking force, its path illuminated by predawn moonlight and periodic artillery flares, continued slowly north. At first light, the vehicles turned northwest, coming to a halt atop an extended sand dune ridge running east to west. To the troops’ complete astonishment, directly downslope in front of them were an estimated 600 to 700 unsuspecting NVA cooking breakfast among the dunes. Corporal Melton recalled, “We were so close to them we could smell their food.”

The ARVN soldiers dismounted from the 10 Marine tanks, which then pulled up abreast. In response to the “Open Fire!” command from Captain Patterson, the detachment leader aboard A-15, they blasted away with their 90mm cannons and machine guns. Some NVA stalwarts fired back wildly with the weapons they had at hand, but tank armor was impervious to bullets.

Despite the deafening blasts of adjacent tank cannons, Patterson was able to contact the ARVN commander on the radio and instruct him to flank the enemy on the west. Once that flanking movement was completed, the ARVN soldiers dismounted their APCs and attacked east toward the coast. The boxed-in, panicked enemy soldiers began a hasty, disorganized retreat north on foot toward the Ben Hai River.

The tanks soon outdistanced the ARVN foot soldiers, and from then on it was indeed a turkey shoot. The shock-and-awe factor of 10 Marine tanks bearing down on the NVA troops overwhelmed them. “It was a wild melee,” said Corporal Claude “Chris” Vargo, the gunner on B-34. “The NVA broke ranks and scattered. Many ran off, leaving their weapons behind. As we were all roaring down on them, firing point-blank with our canister and beehive rounds [steel darts], I lost count of how many dead NVA we passed.”

Sergeant Sal Soto, B-34’s tank commander, saw the effects of the beehive ammunition. “They practically vaporized the NVA caught in the open,” he said. “When we fired that round and it detonated, hundreds of inch-long steel darts exploded out in all directions. Sometimes, all that remained of an enemy soldier were a few body parts enveloped in a pink mist cloud.”

From his perspective aboard the tank retriever, Captain McQueary witnessed several Alpha Company tanks, led by gung-ho platoon Staff Sgt. (first name unavailable) Waggle, roar into the NVA’s battalion command center with their machine guns chattering. “Our tanks crushed every bunker they rolled over, then shot down the fleeing bunker occupants,” McQueary said. “Several bunkers had secondary explosions when the tanks fired HE [high explosive] into them.”

At one point, despite all the smoke and dust swirling around him, Corporal Melton spotted a two-man rocket-propelled-grenade team rise up from behind a nearby bush, attempting to fire at Waggle’s tank. Melton pulled out an M14 rifle stowed inside his turret and squeezed off several well-placed rounds, taking out both enemy soldiers.

Corporal Eddie Miers, the soft-spoken but hard-charging tank commander of A-14, with “The Believer” lettered on his main gun barrel, spotted an NVA soldier hiding in some bushes atop a sand dune. He directed his driver, Pfc. Harold Schossow, to steer their tank in the enemy’s direction. As Schossow pulled the bow of his tank up into the bushes, he saw the terrified look on the man’s face.

“He knew he had two choices: surrender or die,” Schossow said. “Fortunately for him, he jumped out and ran toward our tank with his hands up.” Miers dismounted, tied up and blindfolded his compliant prisoner, and then loaded him aboard the tank. The enemy soldier was turned over to South Vietnamese authorities at Gio Linh later that evening; it turned out he had valuable information for his South Vietnamese captors.

Patterson made radio contact with a Marine Corps UH-1D helicopter in the area and brought it into the fray. The awesome firepower of a heavily armed Huey was something to behold. It was equipped with 14 2.75-inch folding-fin air-to-ground rockets, and four 7.62mm M60 machine guns were mounted for forward firing. Two door gunners, one on each side of the copter, manned M60 machine guns. The Huey swooped down and unloaded its deadly ordnance upon the fleeing NVA soldiers.

As the morning wore on, an increasing number of mortars, rockets and other artillery was fired at the tankers from enemy positions north of the Ben Hai. Soto experienced a near miss by a 122mm rocket that rocked his tank. None of the tanks was disabled. “A few of our tanks suffered damage to their searchlights, vision blocks and antennas from flying shrapnel, but we didn’t lose anybody,” Melton said.

Under the Sav-a-Plane policy that top U.S. military commanders put in place the previous year, the Marines could not call for artillery fire to neutralize the enemy’s guns north of the Ben Hai as long as friendly aircraft were in the attack area. This rule was imposed after two incidents at Con Thien when Marine Corps helicopters were shot down by “friendly fire.” The first incident occurred on Sept. 25, 1966. A UH-34D helicopter from Medium Helicopter Squadron HMM-161, Marine Air Group16, which had just picked up a casualty, was climbing for altitude when an American artillery shell blasted it out of the sky, killing all five men aboard.

A second incident occurred on May 12, 1967, as a UH-34D from squadron HMM-363, the “Red Lions,” was lifting off from the landing zone at Con Thien. It was about 100 feet in the air when a mortar shell fired from Con Thien struck the pilot’s side of the craft, instantly killing him and his crew chief. The helicopter crashed about 900 yards south of the Con Thien perimeter. Miraculously, the co-pilot and door gunner survived.

Once the Huey called in by Patterson had expended its ammo and left the DMZ attack area, the artillery firebases immediately below the eastern DMZ were free to train their guns on the known and suspected enemy positions north of the Ben Hai. “The results were almost instantaneous,” recalled Gunnery Sgt. Baldwin, the Bravo Company 3rd Platoon leader. “That friendly artillery fire support drastically reduced the amount of enemy incoming we were taking.”

An aerial observer spotted a camouflaged enemy encampment on the north bank of the Ben Hai River. Three Bravo Company tanks led by Baldwin ranged in with their cannons and destroyed the camp, subsequently determined to be a training site for frogman commando teams. The Bravo tankers also fired at several large boats circling in the river, sinking two.

Later that afternoon, Patterson ordered the Marine and ARVN units, which had expended nearly all of their 90mm and machine gun ammunition, to leave the DMZ and return to the assembly area south of Gio Linh. As the units departed, they ran into a few NVA diehards attempting to ambush them from the west. Fortunately, Corporal Melton in the lead tank still had three 90mm high-explosive rounds in the turret. He ordered his gunner, Lance Cpl. Ronald Floyd, to open fire, and that helped clear the way for the others.

McQueary’s tank retriever crew spotted an abandoned U.S. Army tank retriever. An American armored unit had been operating in northernmost Quang Tri province and the eastern DMZ earlier that spring, but it had suffered heavy losses trying to go it alone, without sufficient infantry, air and artillery support. The Army pulled out, leaving the DMZ for the Marines to handle.

The tank retriever had suffered serious mine damage—several road wheels were blown off and one track was broken loose. The Army crewmen had abandoned their vehicle with all of its weapons, communications equipment and everything else still intact. That was a shocking revelation to the Marines, who would never abandon one of their armored vehicles on the battlefield in that condition.

After conferring with his executive officer, 1st Lt. Jim Spalsbury, McQueary determined that the retriever was not salvageable. “We did some selective interchange [McQueary’s preferred term for scavenging parts] and then blew the Army retriever in place.”

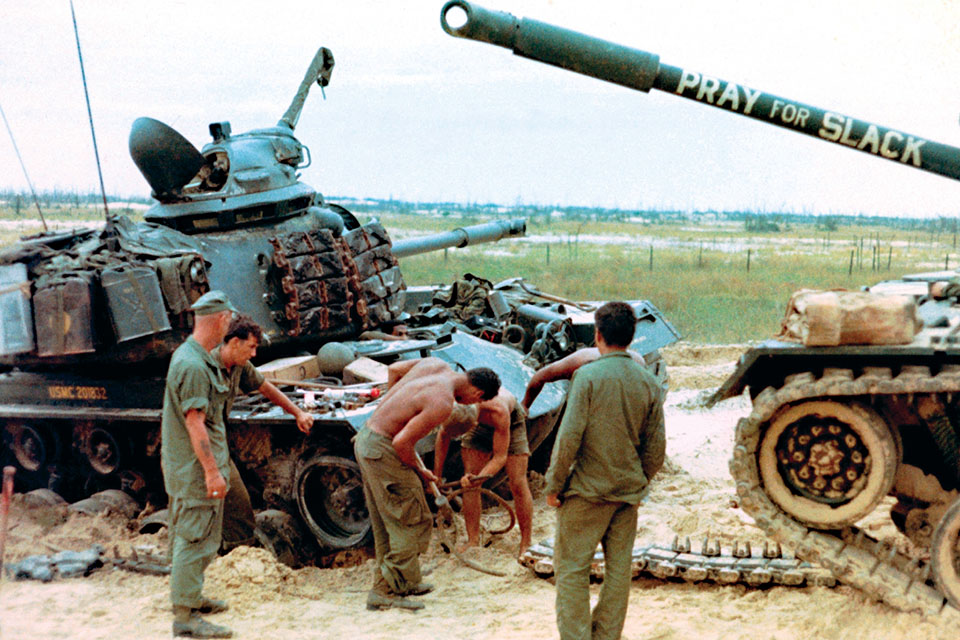

As they continued on, the Marine and ARVN tracked vehicles traveled through an area where Marine and Navy jet fighters had unloaded excess ordnance before returning to their aircraft carriers, but all of them made it through that hazardous area unscathed. Farther south, however, they made a wrong turn and entered an unmarked minefield outside of Gio Linh. The Marines there frantically signaled the tanks to stop, but it was too late. Waggle’s tank ran over and detonated an anti-tank mine.

“When Waggle’s tank hit that first mine, I saw a set of road wheels go flying up in the air,” recalled Soto. “I knew we were in for it after that.” The damage was sufficiently repaired with the aid of the tank retriever crew, and the “short-tracked” tank could be driven under its own power.

Shortly after that incident, Blakemore’s tank and McQueary’s tank retriever also detonated anti-tank mines. Despite having to duck sporadic enemy mortar and artillery fire, the crewmen on those armored vehicles were able to make the temporary repairs necessary to move out of that minefield and head for the assembly area south of Gio Linh.

After the Marine attack, there was no longer any threat of an autumn offensive by the NVA’s 1st Battalion, 138th Regiment. The regiment’s shell-shocked survivors were pulled back north across the Ben Hai River to regroup and refit. U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Richard G. Stilwell, the XXIV Corps commander, reported to General Creighton Abrams, the top U.S. combat commander in Vietnam: “The 1st Battalion, 138th NVA Regiment, was to have attacked south across the DMZ last night; it will do no attacking for some time to come!”

Operation Lam Son 250 was a tanker’s dream. Participants at Vietnam veteran reunions still refer to it as the “DMZ turkey shoot.” U.S. Marine tanks were credited with 189 enemy killed and 70 “probables” out of a total of 421 reported. All tank and retriever crewmen and attached personnel were authorized to wear the Meritorious Unit Commendation ribbon. The remarkably successful Marine-ARVN operation on Aug. 15, 1968, may not have received coverage in the American press, but the actions of those who fought there won’t ever be forgotten by the participants.

James P. Coan was the platoon leader of 1st Platoon, Alpha Company, 3rd Tank Battalion, for nine months during 1967-68. He had just become the executive officer of Alpha Company when Lam Son 250 occurred. Coan is the author of Con Thien: The Hill of Angels, University of Alabama Press, 2004.

First published in Vietnam Magazine’s December 2016 issue.