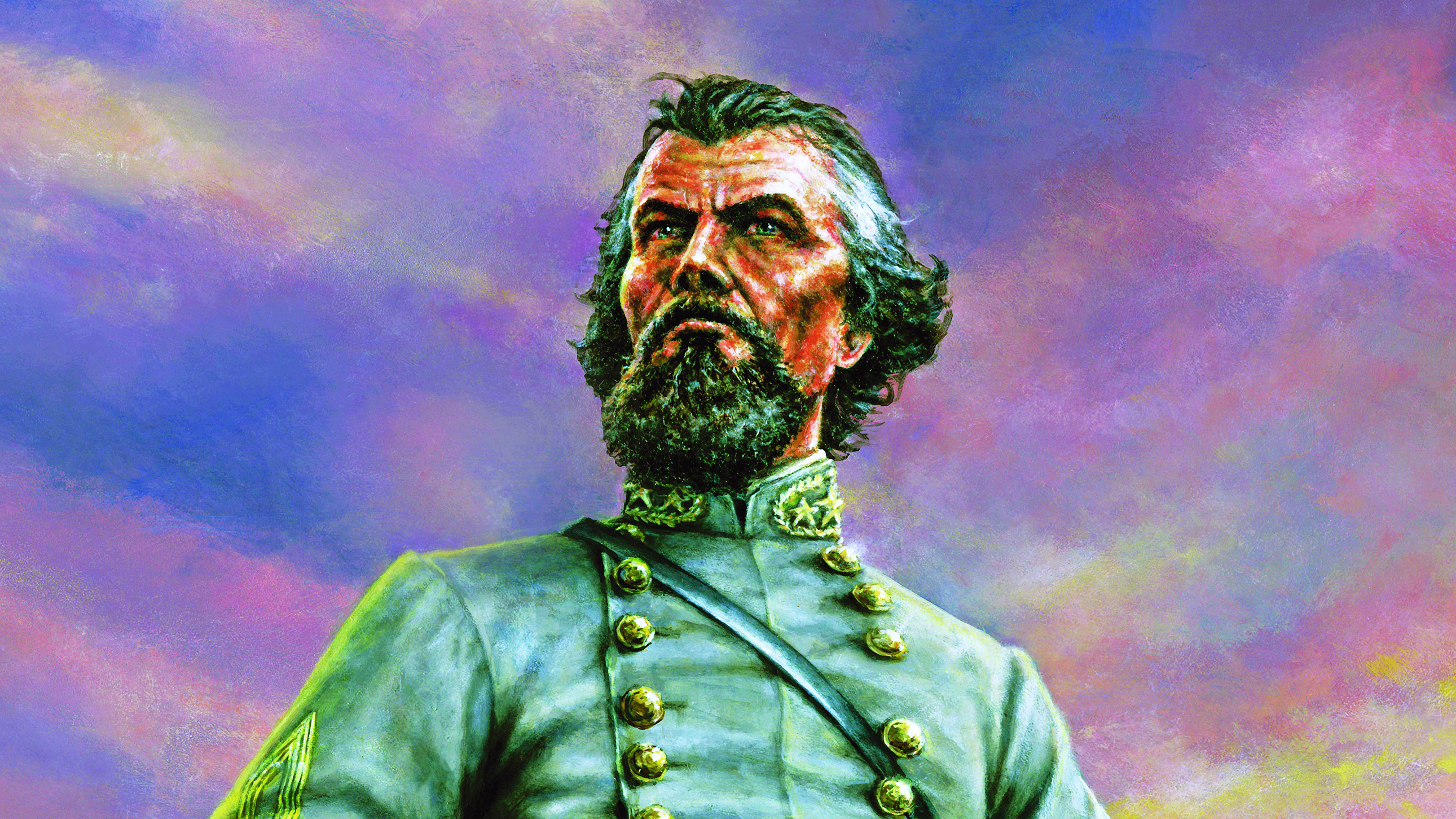

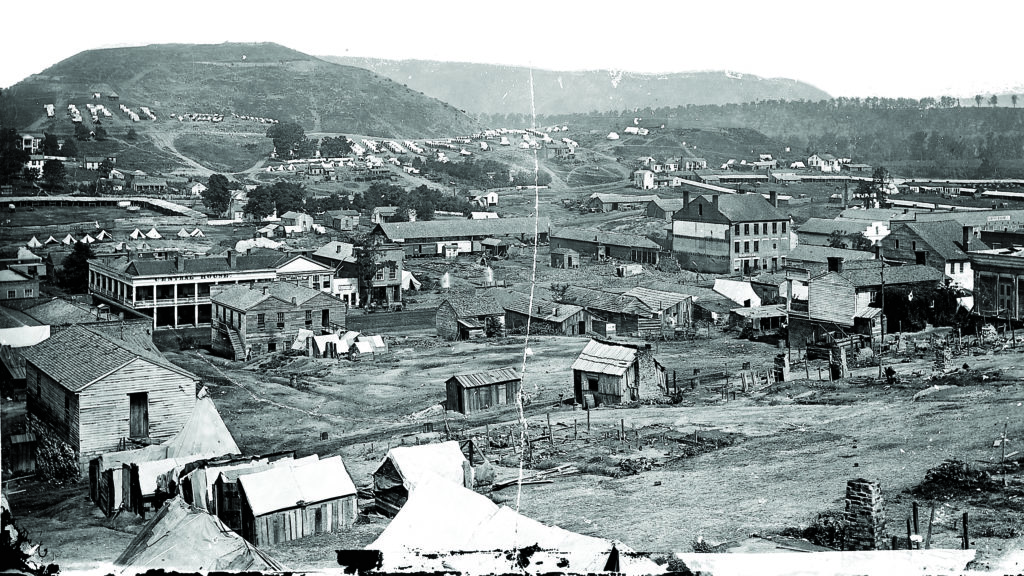

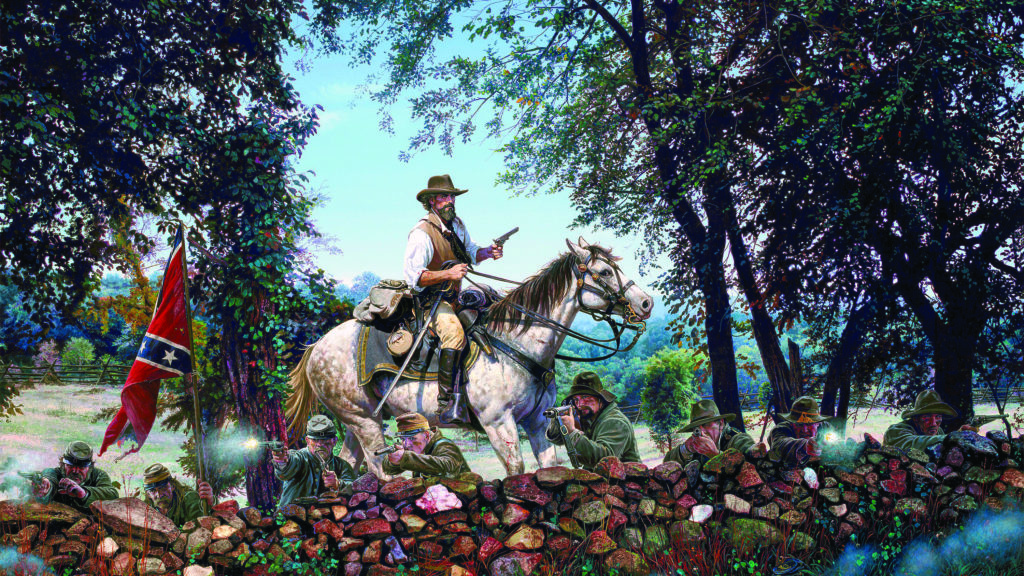

ON SEPTEMBER 30, 1863—as the story has gone for the past 120 or so years—Confederate Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest had a stunning confrontation with General Braxton Bragg in the Army of Tennessee commander’s tent on Missionary Ridge at Chattanooga. Ten days had passed since the Confederates’ remarkable victory over Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland at Chickamauga. Bragg and his army had the Federals encircled in Chattanooga and had initiated a siege promising to alter the entire war in the Western Theater. Still, there was grumbling in the Confederate ranks. Many of Bragg’s subordinates, including Forrest, were reportedly livid that he had let a golden opportunity slip away in the wake of the Chickamauga triumph by failing to pursue the discombobulated Federals with any urgency and allowing Rosecrans to regroup his forces in Chattanooga.

Forrest’s apparent discontent with Bragg was generally believed to extend back to April 1862 and their time together at Shiloh. The last straw, however, seemed to be a mix-up in orders following the September 19-20 fighting at Chickamauga. Ordered to prevent Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s Union army from coming to Rosecrans’ aid, Forrest fought for several days between Chattanooga and Knoxville. While doing so, he learned that his rival, Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, had been made head of the Army of Tennessee’s entire cavalry and—by mistake—was led to believe that Wheeler was now in command of all four of his brigades.

Understandably, Forrest expressed his displeasure to Bragg. How and where exactly those objections played out has been the subject of controversy since. According to John Wyeth’s 1899 book Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest, Forrest burst into Bragg’s tent and blared, “I have stood your meanness as long as I intend to….You have played the part of a damned scoundrel, and are a coward, and if you were any part of a man I would slap your jaws and force you to resent it. You may as well not issue any more orders to me, for I will not obey them, and I will hold you personally responsible for any further indignities you endeavor to inflict upon me….If you ever again try to interfere with me or cross my path it will be at the peril of your life.”

An altercation of that nature with a superior would have ended the career of just about any soldier or officer. Granted, the Wizard of the Saddle was no ordinary soldier, but it is nevertheless puzzling, if the story is indeed true, that Bragg meekly accepted Forrest’s diatribe without comment and never bothered to discipline him. Bragg’s solution was to transfer three of Forrest’s brigades into Wheeler’s Corps, but not Forrest himself.

In the century-plus since Wyeth’s book, the Forrest-Bragg imbroglio of September 1863 has essentially been accepted as gospel. But did the clash happen as reported? A closer look at The Official Records of the War of the Rebellion and other postwar primary sources depicts a different picture of the two generals’ relationship—that they were not actually bitter enemies, but had legitimate respect for the other.

The source of the anecdote Wyeth revealed in Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest was James Cowan, a former surgeon in the Confederate Army and Forrest’s cousin. Cowan claimed to be the only eyewitness to the meeting between the generals that September day. [See full text of Cowan’s account, below]

Cowan’s “high standing,” Wyeth offered in his 1899 edition, “renders his statement absolutely reliable.” Only it wasn’t. Both Confederate generals had died years before Cowan shared the story with the biographer—Bragg in 1876, Forrest in 1877—but Wyeth, it seems, ignored conflicting evidence not only in the Official Records but also Forrest’s 1868 pseudo-autobiography, The Campaigns of Lieut.-Gen. N.B. Forrest, and of Forrest’s Cavalry. Wyeth even contradicted Cowan by writing: “The President of the Confederacy [Jefferson Davis] was on the scene when this quarrel occurred, and he took the part of Forrest.”

In 1902, James Mathes repeated Cowan’s tale in his book General Forrest, and expanded on the president’s role: “[C]oming upon the scene about the time of the disagreement [Davis] proved to be his stanch friend. He would not entertain the idea of a resignation, but wrote Forrest a gracious and encouraging letter, appointing a day for a meeting at Montgomery, Ala.”

Wyeth eventually decided that Cowan had either fabricated or exaggerated his account. In 1908, he published a revision of his book, adding a 12-page postscript containing “incidents” in Forrest’s life “not known to me” when he had penned the first version. In addition, Wyeth rewrote pages 264 through 267, omitting mention of Cowan’s account as well as the presence of Davis. Rather than admit a mistake or simply denounce the doctor, it appears Wyeth wanted the story forgotten.

Cowan, however, stood by his account until his death in 1909, and Forrest enthusiasts were quick to weigh in. Citing Wyeth, John Morton repeated Cowan’s account in his 1909 book The Artillery of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Cavalry, adding “Maj. M.H. Clift has told Captain Morton that he had heard of the incident at the time it took place” and queried Forrest about it after the war. “The General,” Morton wrote, “told him the facts were about as he had heard.”

When “the incident” was said to have occurred, Captain Moses Clift was serving on the staff of Colonel George Dibrell, one of Forrest’s brigade commanders. Morton seemed willing to stretch the truth about President Davis, who he wrote “was at headquarters when the quarrel occurred, and, without taking official action in the matter, wrote General Forrest a personal letter in his own hand, appointing a meeting at Montgomery.” Davis, though, was in Richmond when the meeting was said to have occurred.His visit to Bragg did not take place until October 9-14.

Wyeth’s 1908 revision went out of print in 1924, two years after his death. Harper & Brothers waited until 1959 to bring out a third edition titled That Devil Forrest: Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest. The publishers acknowledged making minor changes to the “original text of the book”; however, they mingled pages 264 through 267 from the two earlier editions and resurrected Cowan’s story as the true version of the generals’ confrontation. The third edition, which was republished in 1989, remains in print. This, of course, has perpetuated Wyeth’s connection with Cowan’s story, though the corrections he inserted in the 1908 version still tend to get overlooked by historians.

Except for Wyeth’s 1908 edition, Cowan’s story has appeared as fact in just about every biography of Forrest since 1899. But Judith Hallock questioned the doctor’s veracity in her 1991 book Braxton Bragg and Confederate Defeat, Volume II, concluding, “Whatever the sequence of events and however dramatic the meeting between Forrest and Bragg…Bragg proceeded to have Forrest transferred.”

Hallock, though, wondered if the altercation had occurred at all and confided as much to historian James Ogden, who agreed with her. Ogden shared their suspicions with David Powell, who published an investigation of the matter in Appendix 4 of his 2010 book Failure in the Saddle. “Unless additional credible contemporary accounts surface,” he maintained, “it is impossible to know with certainty whether this incident really took place.”

Reexamining the evidence in Braxton Bragg: The Most Hated Man of the Confederacy (2016), Earl Hess opined that Cowan’s account was unlikely but stopped short of declaring it a complete fabrication.

For more than a century, the controversy has led historians to perhaps misread the Confederate high command in the Western Theater. A closer look is warranted.

In early June 1862, General P.G.T. Beauregard desperately needed a senior colonel to organize a brigade of cavalry at Chattanooga and promised Forrest a promotion if he would undertake the task. For the good of the cause, Colonel Forrest chose to move on from his regiment. A week later, when Bragg replaced Beauregard as commander of Department No. 2, he made no attempt to block Forrest’s promotion and in fact welcomed the new brigadier as commander of his cavalry.

Rather than join the army when first ordered in August, Forrest opted to continue raiding behind enemy lines while also trying to gather intelligence about enemy movements. Bragg had divided his army into two wings before Forrest reported in person in early September; when Forrest arrived, Bragg reinforced his brigade and assigned it to the Right Wing. But on the night of September 20—exactly one year prior to the Confederates’ Chickamauga success—Forrest’s horse fell and rolled over onto him, dislocating the general’s right shoulder. Despite the pain, Forrest remained with his command, riding in a buggy.

This sufficed while his troopers remained near Bardstown, Ky., but when they resumed marching it became evident that Forrest would not be able to keep up with his men. Bragg, however, never forced Forrest to admit his limited capacity or insist he take medical leave. Instead, thinking Forrest might recover more quickly and be of more benefit by leading a recruiting effort in the region, Bragg placed him in charge of operations in Middle Tennessee—assigning him four companies. Forrest graciously accepted the assignment and, in fact, quickly raised another brigade.

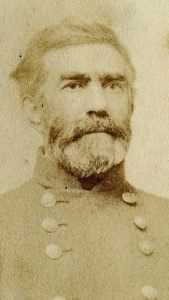

Later that fall, Bragg reorganized his army. Even though Forrest was senior brigadier, ahead of John Hunt Morgan, Bragg was convinced both were better at raiding than gathering intelligence or guarding the army. Conversely, Brig. Gen. Joseph Wheeler had recently demonstrated proficiency handling cavalry attached to the army. Bragg therefore secured an appointment to major general for Wheeler, but he left Forrest and Morgan as independent brigade commanders instead of having them serve directly under Wheeler. All the same, while Wheeler didn’t command their brigades, as chief of cavalry he, not Bragg, was responsible for supplying their arms and munitions.

After a raid through West Tennessee in December 1862 followed by a sabbatical, Forrest met with Bragg in Shelbyville, Tenn., on January 26, 1863. He learned that Wheeler had borrowed 800 of his troopers for a raid along the Cumberland River. Forrest hurried to join his troops, arriving in time to object to Wheeler’s February 3 attack on Dover, Tenn. Wheeler attacked anyway, and, after losing more than 200 men in that failed attack, Forrest swore that his days serving under Wheeler were over. He reportedly insisted the general inform Bragg “that I will be in my coffin before I will fight again under your command.”

Although Wheeler made no mention of the confrontation in his report of the expedition, Bragg must have become aware of it. After all, rather than sack Forrest for what was incontrovertibly insubordination, he instead showed considerable respect for his subordinate by having him and his brigade transferred to Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn’s command in West Tennessee. Even though Van Dorn and Forrest nearly drew swords on each other in April, they did work well together. When a cuckolded husband shot the notoriously licentious Van Dorn to death in Spring Hill, Tenn., on May 7, 1863, Bragg offered Forrest a promotion and command of Van Dorn’s Corps. Forrest declined, but Bragg nevertheless assigned him the command and lobbied for his promotion to major general.

When Bragg was instructed to send one of Van Dorn’s old divisions to the fighting outside Vicksburg, Miss., he elected to keep Forrest and his men with him in Tennessee. After Rosecrans’ Federals turned the Confederate army’s right flank near Tullahoma, Bragg was forced to abandon Middle Tennessee on July 3, 1863. He feared that Rosecrans was headed for Chattanooga and would cross the Tennessee River above the city. His decision to shift Forrest’s position to guard the army’s right flank—independent of Wheeler, who was guarding the left—is a telling sign of Bragg’s appreciation and respect for Forrest.

Logistical problems stalled Rosecrans’ advance, and briefly it appeared the Union threat to Chattanooga had been minimized. On August 9, Forrest wrote Adj. Gen. Samuel Cooper in Richmond to request an independent command of about 500 men, to be charged with disrupting traffic on the Mississippi River north of Vicksburg. Forrest believed he could also use such an opportunity to attract recruits from behind enemy lines.

In endorsing the request on August 14, Bragg noted: “I know no officer to whom I would sooner assign the duty proposed, than which none is more important, but it would deprive this army of one of its greatest elements of strength to remove General Forrest.”

Cooper, in Richmond, passed the letter on to Secretary of War James Seddon on August 26, but Cooper learned that Seddon had already received a copy from Jefferson Davis, who wanted Bragg’s opinion. How? Because Forrest had written the president directly on August 19 and enclosed a copy of his request, stating he believed it was “likely” Bragg would not forward it. Seddon submitted the original to Davis on August 28. “The indorsement [sic] of General Bragg,” he wrote, “indicated the propriety of a postponement. Subsequent events have served to render the proposition more objectionable. Whenever a change of circumstances will permit, the measure may be adopted.”

By that time, Rosecrans had reached the outskirts of Chattanooga, and on August 21 had begun shelling the city from across the river. The following day, Bragg learned that Burnside was advancing on Knoxville with the Army of the Ohio. Convinced still that Rosecrans would cross the Tennessee River upstream, Bragg knew he needed Forrest more than ever. On September 3, he even assigned the cavalryman a second division, which returned him to corps command.

To Bragg’s dismay, Rosecrans outmaneuvered Wheeler—on the Confederate left—and crossed the river downstream. That forced Bragg to abandon Chattanooga and move south into Georgia, where a month later he rectified the situation by roundly defeating Rosecrans at Chickamauga. But again, with Rosecrans now besieged in Chattanooga, Bragg could not afford to ignore the threat from Burnside in Knoxville. On September 25, he sent Forrest with four brigades to engage Burnside’s vanguard near Cleveland, Tenn., just north of Chattanooga.

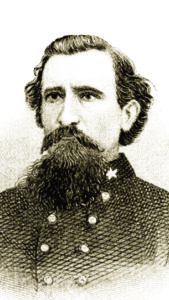

Before midnight that day, however, Bragg sent an order to Forrest “to turn over his command, except two Brigades, to Maj Gen Wheeler.” When that order reached Forrest is unknown, but Bragg’s adjutant, Colonel George L. Brent, noted on September 26: “A strong protest was recd this morning from Genl Forrest against the order turning over his command to Wheeler. It was full of Just complaints.”

By the time Bragg learned from Brent of those objections, Forrest’s troopers had already cleared the south bank of the Hiwassee River of Federals, and were in hot pursuit of Colonel Robert K. Byrd’s fleeing mounted infantry. Reinforced by Colonel Frank Wolford’s cavalry, the Yankees rallied near Athens to stem Forrest’s juggernaut for at least a few hours before scurrying on to Philadelphia, Tenn. Forrest resumed his pursuit on September 27, driving the Federals back closer to Knoxville.

Concerned primarily with cutting off supplies to Rosecrans, Bragg would have been content had Forrest simply halted any Federal advance at Cleveland. When Bragg learned the Federals had barely crossed the Hiwassee and Forrest was nearly in Knoxville, he became angry, suspecting the “Wizard” had gone off on an unnecessary raid. Bragg wanted Forrest’s troopers to team with Wheeler in disrupting Rosecrans’ supply line, and was confident he now had time to swap in infantry for Forrest’s cavalry to block Burnside.

As Bragg fumed, “The man…does not know anything of cooperation. He is nothing more than a good raider.”

When Forrest encountered Union infantry near Loudon on September 28, he realized the odds had shifted against him and turned back. Later that day, Brent wrote Forrest that Bragg desired he “without delay turn over the troops of your command previously ordered to…Wheeler.”

Where Forrest was when that order reached him is unclear, but he did notify Wheeler that he was en route and then suggested, “Would it not be well to have the fortifications at Charleston [Tenn.] repaired and artillery placed in position there in order to defend the crossing if necessary?” Forrest believed his troopers would be of better use opera-ting along the Hiwassee. Wheeler responded with a request for any spare ammunition for small arms and artillery, to which Forrest replied that he had none to spare. “Have ordered General [Henry B.] Davidson and General [Frank C.] Armstrong to you, and…[have] retained Dibrell’s and [John] Pegram’s brigades,” Forrest wrote. “They are all without rations…[and I] am satisfied that neither men nor horses are in condition for the expedition.”

The brigades assigned to Wheeler reached Athens that night and joined him the following evening. Wheeler was shocked by their appearance and reported after the raid that Forrest’s brigades “were mere skeletons, scarcely averaging 500 effective men each.” All “were badly armed [and] had but a small supply of ammunition.” Moreover, “their horses were in horrible condition…[and] the men were worn out, and without rations.”

Two mounted Federal brigades began pursuing Forrest from Loudon on the 28th but eventually called off the chase. Forrest then established his headquarters at Cleveland, prepared to defend the Hiwassee’s vulnerable fords.

Bragg, it must be noted, was angry with himself, too. Hurt by faulty intelligence, he had miscalculated the situation in issuing Forrest his original orders on September 25, and Forrest had compounded Bragg’s mistake by successfully driving back the enemy as he had. Now, the longer Forrest took to comply with Bragg’s orders, the greater the delay was to Rosecrans’ benefit.

Another significant glitch was the order Bragg mistakenly issued on the 29th assigning Wheeler “command of all the cavalry in the Army of Tennessee.” Wheeler, thinking he now had the authority to do so, issued a direct order to Dibrell, which quickly drew a protest from Forrest. It was a good sign for Forrest, however, when Bragg notified Wheeler on September 30 “that the brigade of Colonel Dibrell shall remain at Cleveland.” When Forrest met with Bragg in early October, according to a report, he received assurances that his entire corps would be returned following Wheeler’s raid on the Federal supply lines.

Forrest didn’t meet with Davis when the president visited the army October 9-14, but Davis and Bragg did discuss the cavalryman. On the 13th, Bragg sent Davis a letter approving Forrest’s transfer to West Tennessee, and Davis left an invitation for Forrest to meet with him in Montgomery, Ala. But matters intensified again on October 20, when, as Brent noted, “Genl Bragg has asked the President to relieve Maj Genl [Samuel Bolivar] Buckner and Brig Genl [William] Preston. Forrest is here and is much dissatisfied. Troubles are brewing in the command.”

The “troubles” concerned other generals, but Forrest had cause to be upset. Wheeler’s raid had ended 12 days earlier, yet the brigades sent to Wheeler from Forrest’s command had not returned. Then on the 17th, Forrest’s other two brigades were ordered “to press vigorously toward Knoxville as soon as possible.” (Forrest was not personally notified of this, likely because he had gone on leave.)

Receipt of Davis’ invitation and the OK for another leave seemed to have satisfied Forrest. While in Dalton, Ga., on October 22, he wrote his report on Chickamauga as well as his subsequent venture beyond the Hiwassee River.

On October 27, he met with Davis in Montgomery, and traveled with him to Atlanta the following day. On the 29th, the president gave Forrest his approved transfer to West Tennessee (along with a letter from Bragg requesting that Davis do so). The next day, Forrest met with Bragg to determine the troops that would accompany him on his new assignment. Despite reported claims to the contrary, Bragg informed Davis on October 31, “General Forrest’s requests are all granted, and he has started for his new field apparently well satisfied.”

With 271 effectives, Forrest headed to Okolona, Miss. Though no longer reporting to Bragg, on December 8 he wrote his former commander a collegial letter, which can be found in the Official Records. He concluded:

I am confident that I shall have in a short time 8,000 effective men in the field, besides some thousand belonging to infantry command, all of whom will be sent back at the earliest possible moment. I am not only willing, but desirous, general, of rendering the country all the service possible in the occupancy and defense of West Tennessee; also to get out from here all the supplies I can for the subsistence of your army. If you can aid me in the services of a general officer or the procurement of arms I shall be thankful, and in turn use every exertion to send to you the absentees from your ranks and supplies, &c., for your troops.

I am, general, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

N.B. Forrest,

Brigadier-General, Commanding.

At the time, Forrest hadn’t learned of his promotion to major general, dated December 4, or that on the 6th Bragg had relinquished command of the Army of Tennessee.

Although it is a reach to say they were friends, the two certainly respected each other for putting the good of the Confederacy first. On October 30, 1863, Brent wrote: “Gen Forrest has been relieved & will go to North Miss & West Tenn. This change is I think injudicious. Coupled with the Existing discontent in the Cavalry it will tend materially to still further impair its usefulness. Forrest with many objections, is…the best Cavalry Commander in the Army.”

Why did Bragg keep Wheeler instead of Forrest? For one, he realized his cavalry needed to be united under one commander. Wheeler outranked Forrest and was considered a better administrator and at least his equal at collecting intelligence. Bragg also recognized that Wheeler had subordinates capable of replacing him if needed. Though Forrest never doubted he was a superior leader and raider than Wheeler, he also believed he could render more effective service elsewhere. Davis and Bragg would concur.

Debunking the account of the Forrest–Bragg confrontation raises a new question, however: Why did Cowan, Mathes, Morton, and so many others since make Bragg the scapegoat? It is a question to which we may never have an answer.

Lawrence Lee Hewitt is co-editor of the Confederate Generals in the Western Theater and Confederate Generals in the Trans-Mississippi collections, and is author of Port Hudson: Confederate Bastion on the Mississippi.

Cowan the Eyewitness?

The following passage, quoting Confederate surgeon James Cowan, appeared on pages 265-266 of John Wyeth’s 1899 first edition of Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest.

I observed as we rode along that the general was silent, which was unusual with him when we were alone. Knowing him so well, I was convinced that something that displeased him greatly had transpired. He wore an expression which I had seen before on some occasions when a storm was brewing. I had known nothing of the letter he had written General Bragg, and was in utter ignorance not only of what was passing in Forrest’s mind at this time, but of the object of his visit to the general-in-chief. As we passed the guard in front of General Bragg’s tent, I observed that General Forest did not acknowledge the salute of the sentry, which was so contrary to his custom that I could not help but notice it.

When we entered the tent where General Bragg was alone, this officer rose from his seat, spoke to Forrest, and, advancing, offered him his hand. Refusing to take the proffered hand, and standing stiff and erect before Bragg, Forrest said:

“I am not here to pass civilities or compliments with you, but on other business. You commenced your cowardly and contemptible persecution of me soon after the battle of Shiloh and you have kept it up ever since. You did it because I reported to Richmond facts, while you reported damned lies. You robbed me of my command in Kentucky, and gave it to one of your favorites—men that I armed and equipped from the enemies of our country. In a spirit of revenge and spite, because I would not fawn upon you as others did, you drove me into west Tennessee in the winter of 1862, with a second brigade I had organized, with improper arms and without sufficient ammunition, although I had made repeated applications for the same. You did it to ruin me and my career.

“When in spite of all this I returned with my command, well equipped by captures, you began again your work of spite and persecution, and have kept it up; and now this second brigade, organized and equipped without thanks to you or the government, a brigade which has won a reputation for successful fighting second to none in the army, taking advantage of your position as the commanding general in order to further humiliate me, you have taken these brave men from me.

“I have stood your meanness as long as I intend to. You have played the part of a damned scoundrel, and are a coward, and if you were any part of a man I would slap your jaws [sic] and force you to resent it. You may as well not issue any more orders to me, for I will not obey them, and I will hold you personally responsible for any further indignities you endeavor to inflict upon me. You have threatened to arrest me for not obeying your orders promptly. I dare you to do it, and I say to you that if you ever again try to interfere with me or cross my path it will be at the peril of your life.”

…The scene did not last longer than a few minutes, and when Forrest had finished he turned his back sharply upon Bragg and stalked out of the tent towards the horses. As they rode away Dr. Cowan remarked, “Well, you are in for it now!” Forrest replied instantly, “He’ll never say a word about it; he’ll be the last man to mention it; and, mark my word, he’ll take no action in the matter. I will ask to be relieved and transferred to a different field, and he will not oppose it.”