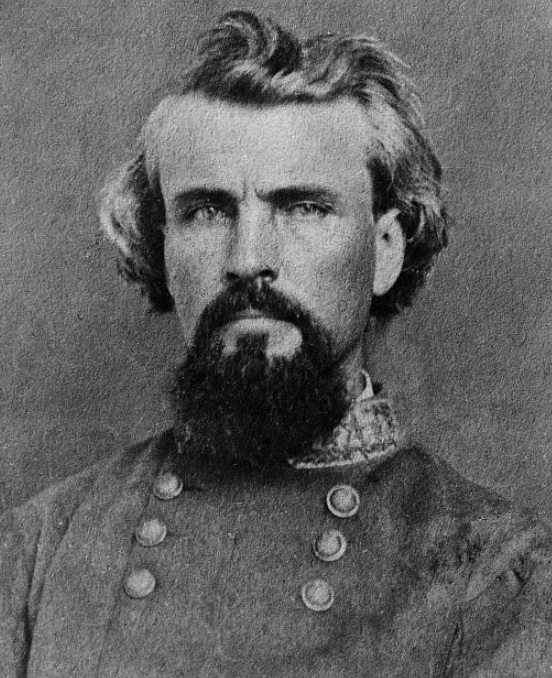

Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest could not have known the whirlwind he was set to unleash as his men closed in on a small isolated fortification on the banks of the Mississippi River north of Memphis on April 12, 1864. Forrest would capture Fort Pillow, with its garrison of Tennessee Unionists and African-American troops, but the victory would become the most controversial moment of his wartime career. The isolated post proved little match for the Confederates, but in the latter stage of the fight Forrest lost control of his men, some of whom killed members of the Union garrison who should have been spared.

By the spring of 1864, Forrest had already created a powerful reputation as “the Wizard of the Saddle” and demonstrated his prowess in raids, pursuits, traditional cavalry roles and departmental operations. He enjoyed a solid record of besting his opponents and making the most of limited resources to accomplish impressive ends. Despite little formal education, Forrest impressed associates with his mental acuity. His ferocity in combat matched his capabilities. By war’s end, he could claim 30 opponents killed in close-hand combat to offset the 29 mounts he lost in such fighting. “He was a host in himself, and a dangerous adversary at any reasonable odds,” observed a future commander, Richard Taylor.

As the Confederate raiders set out on March 22, Forrest looked to ground in western Tennessee and Kentucky that had already proven lucrative for his command. Earlier raids through the region had secured supplies and recruits and thrown his opponents into nervous turmoil. Determined to make his mark once more, Forrest dispatched various forces to obtain maximum results. Colonel William L. Duckworth approached Union City, Tenn., employing the common Forrest stratagem of bluff and intimidation to convince his opponent, Col. Isaac R. Hawkins, to surrender some 500 men and 300 horses. Captain Henry A. Tyler attempted a similar ruse at Columbus, Ky. With only 150 men at his disposal, Tyler’s command was too weak to assault the Union garrison directly. Using the name of his superior, “A[braham] Buford,” to give the impression of a larger force, the captain offered his counterpart terms that also took a racial tone. “Should you surrender, the negroes now in arms will be returned to their masters,” Tyler explained. “Should I, however, be compelled to take the place, no quarter will be shown to the negro troops whatever; the white troops will be treated as prisoners of war.” Tyler knew that such a hyperbolic demand was the only means by which he could hope to capture the post. So did the Union commander, who refused to surrender.

In the meantime, Forrest headed for Paducah, Ky. The river town promised greater spoils, but offered more significant challenges. In addition to the garrison, which included African-American troops and featured formidable Fort Anderson, the Union defenders enjoyed the benefit of support from two gunboats, the Paw Paw and the Peosta. A foolhardy and unauthorized assault by Col. Albert P. Thompson resulted in that officer’s death and additional casualties. A bloodcurdling surrender demand, laced with Forrest’s traditional threat of “no quarter,” failed. Yet the aggressive Confederate general remained undeterred.

He had inflicted considerable damage, setting the Union losses in his various operations at 79 killed, 102 wounded and 612 captured, while placing his own at 15 killed and 42 wounded. But as he turned back to Tennessee, he recognized that more remained to be achieved—and chose his next target: “There is a Federal force of 500 or 600 at Fort Pillow, which I shall attend to in a day or two, as they have horses and supplies which we need,” he reported on April 4.

Situated on a high bluff on the eastern bank of the Mississippi, Fort Pillow was originally part of the Confederate defense network for Memphis, but was occupied by Federal forces in June 1862 when Rebel troops evacuated it after the fall of New Madrid and Island No. 10. For two years, it was an important Union outpost and river landing. Long lines of outer entrenchments required far more men to occupy than the garrison of 557–580 black and white Union troops allowed. The innermost of the works consisted of a ditch of 8 feet and a parapet 6–8 feet tall and 4–6 feet across with embrasures for artillery pieces to cover the approaches. Approximately 125 yards long, this interior line faced east to protect the land side, with an open rear to the river and a small creek below. Ravines cut into the loess soil on either side, the result of water runoff from the higher surrounding ground. In addition, the defenders had the benefit of a Union gunboat, New Era, to assist as needed.

Brigadier General James Chalmers led the first Confederate troops to appear before Fort Pillow. His men drove the Union pickets from the outer lines and secured the higher ground of the middle line of trenches from which sharpshooters could fire into the interior works. The defenders “suffered pretty severely in the loss of commissioned officers by the unerring aim of the rebel sharpshooters,” noted Union Lt. Mack J. Leaming. The most devastating of these losses came at 9 a.m. when the garrison commander, Maj. Lionel F. Booth, suffered a fatal wound while standing near one of the fort’s embrasures. Authority passed to Tennessee Unionist, Maj. William F. Bradford.

Forrest arrived at 10 a.m., and immediately acquainted himself with the opposing array and the terrain features. But he left himself exposed to Union fire and suffered a bruising fall. Rejecting advice that he remain on foot—because he was “just as apt to be hit one way as another, and…could see better where he was”—the general lost two more horses in the course of the day’s fighting.

Forrest identified several features that offered his attacking forces important advantages. Rows of barracks just outside the interior works could provide cover for advances in that quarter. The Federals sought to eradicate these structures, but only managed to burn the row closest to the fort before Confederate fire drove them back. “From these barracks the enemy kept up a murderous fire on our men despite all our efforts to dislodge him,” Leaming reported.

Forrest also quickly realized he could move troops through the ravines toward the landing below the fort, cutting the garrison off from potential relief or escape. He ordered Capt. Charles W. Anderson and Col. Clark S. Barteau to secure those access points, instructing Anderson to “hold my position on the bluff, prevent any escape of the garrison by water, to pour rife-balls into the open [gun]ports of the New Era when she went into action, and to fight everything blue betwixt wind and water until yonder fag comes down.”

Throughout the morning and into mid-afternoon, the Confederates invested the fort. By 3:30 p.m., Forrest deemed that he could storm the position, but opted for a less bloody conclusion if it could be achieved. “The conduct of the officers and men garrisoning Fort Pillow has been such as to entitle them to being treated as prisoners of war,” he noted in a message to the fort’s commander. “I demand the unconditional surrender of this garrison, promising you that you shall be treated as prisoners of war.” Forrest softened the normally dire consequences attendant to refusal, but added plainly, “Should my demand be refused, I cannot be responsible for the fate of your command.”

Bradford sought to buy time to consider his options. Replying under Booth’s name, he requested an hour to confer with his officers. Forrest worried the delay might complicate matters for the Confederates if more Union vessels arrived on the river, and reduced the time to 20 minutes. Indeed, the steamer Olive Branch appeared during the truce, with troops and artillery bound for the North from New Orleans. Ultimately, each side would complain that the other had taken steps during the negotiations that constituted a breach of the truce.

Finally, Forrest tired of waiting for the Union commander to reach a decision. “In plain and unmistakable English. Will he fight or surrender?” he demanded. Bradford responded brusquely: “We will not surrender.” Forrest would have to fight to secure the fort and its coveted resources.

Forrest’s men needed little prodding to advance against a fort that contained Tennessee Unionists and African-American troops. The antagonists had long harbored intense hostility toward each other, and taunts by the Federals from the supposed security of the earthworks further exacerbated matters. “During the truce,” one Confederate officer remembered, “they openly defied us from the breastworks to come and take the fort.” Forrest appealed to the soldiers’ home pride when he dispatched staff to tell the brigades that “I should watch with interest the conduct of the troops; that Missourians, Mississippians, and Tennesseans surrounded the works, and [I] desired to see who would first scale the fort.”

At the signal, the Confederates raced across the space separating them from the ditch and earthworks. Some helped others scramble onto the parapet. The speed with which they reached the works left little opportunity for Union fire. Some of the defenders began to break for the rear while others tried to resist the Confederate tide now washing over them. “During the last attack, when the rebels entered the works, I heard Major Bradford give the command, ‘Boys, save your lives’ ” one witness recalled. A nearby officer urged further resistance, “but when the major, turning around and seeing the rebels coming in from all sides, said, ‘It is of no use any more,’…the men left their [artillery] pieces and tried to escape in different directions and manners.”

Unfortunately for the Union defenders, New Era was in no position to help. In addition to supporting the fort with its guns, the vessel was supposed to provide covering fire should the garrison be forced to retreat. As Confederates overran the fort, “Major Bradford signalled to me that we were whipped,” the gunboat commander, Capt. James Marshall, later testified. “We had agreed on a signal that, if they had to leave the fort, they would drop down under the bank, and I was to give the rebels canister.” But the gunboat had already expended much of its ordnance and the commander wished to avoid the risk of further exposure from the riflemen on the banks.

What happened next led to charges against Forrest and his troops that have smoldered for 150 years.

In the chaos and panic of broken and pursuing troops, any sense of order evaporated below the bluff. Many tried to surrender, while others plunged into the water to escape. Still others continued to resist. “The victory was complete,” Forrest subsequently reported, “and the loss of the enemy will never be known from the fact that large numbers ran into the river and were shot or drowned. The river was dyed with the blood of the slaughtered for 200 yards.” Although he overestimated the Union garrison at 700, Forrest thought some 500 of these perished. “It is hoped that these facts will demonstrate to the Northern people that negro soldiers cannot cope with Southerners,” he wrote in his report.

The Federals paid a heavy price for resistance. Historians John Cimprich and Robert C. Mainfort Jr. set the deaths or mortal wounds among the garrison at between 277 and 297, or 47–49 percent of a total ranging from 585 to 605 men. Among white units, 31–34 percent were killed. But 64 percent of the black units died. The toll for the attacking Confederates rested at only 14 killed and 86 wounded.

The stunning toll among black troops—and allegations by survivors of a killing spree by Rebel soldiers—prompted the United States government to take a special interest in the events at Fort Pillow. A congressional investigation led to the conclusion that the Confederates had “treacherously gained” advantages over the defenders during the truce and then engaged in “an indiscriminate slaughter” after the fort had fallen, “sparing neither age nor sex, white or black, soldier or civilian.” The result was a “massacre” that had featured terrifying atrocities, including the burning and burying of live victims, according to witnesses. “No cruelty which the most fiendish malignity could devise was omitted by these murderers,” the investigators reported. Nor could the excesses be excused by the nature of battle, since “the atrocities committed at Fort Pillow were not the result of passions excited by the heat of conflict, but were the results of a policy deliberately decided upon and unhesitatingly announced.”

The remaining question was whether Forrest himself had allowed—or even ordered—the slaughter, or if not, whether he had done anything to stop it. Much of the evidence placing Forrest at the heart of the misconduct was circumstantial, from those who heard his name mentioned or who purported through questionable testimony to witness his involvement. Jacob Thompson insisted he saw Forrest at the scene of the killings and described the more than 6-foot-tall general inconveniently as “a little bit of a man.”

While the killing at Fort Pillow outraged the North, it brought Southern recriminations, too. Achilles V. Clark, a Confederate sergeant and participant, revealed the most damning evidence against his chief in a dramatic letter to his sisters on April 19, in which he urged them “to judge whether or not we acted well or ill.”

The Confederate troops “were so exasperated by the Yankee threats of no quarter that they gave but little,” he wrote. “The slaughter was awful— words cannot describe the scene. The poor deluded negroes would run up to our men, fall upon their knees and with uplifted hands scream for mercy but they were ordered to their feet and then shot down.” According to Clark, few survived the killing. He wrote that he took steps to “stop the butchery and at one time had partially succeeded. But Gen. Forrest ordered them shot down like dogs and the carnage continued. Finally our men became sick of blood and the firing ceased.” It was clear that he saw men killed in cold blood, but less clear that Forrest participated, or that the men acted as they thought their commander expected.

Forrest’s defenders also often depended on hearsay rather than fact. Two exceptions came from a Confederate participant, Samuel H. Caldwell, and a Union surgeon, Charles Fitch. Caldwell wrote home shortly after the battle that he had experienced “the most horrible sight that I have ever witnessed.” When Union troops “refused to surrender” the decision “incensed our men & if General Forrest had not run between our men & the Yanks with his pistol and sabre drawn not a man would have been spared.”

Fitch recalled seeking protection from the Confederate commander while death swirled around him. The doctor noted that Forrest was engaged “sighting the Parrott Gun [in the fort] on the Gun boat,” when he approached him. Fitch informed Forrest that he was “the Surgeon of the Post,” to which the Confederate responded that he must be with “a Damn N—— regiment” or “a Damn Tenn. Yankee then.” Fitch confounded Forrest by explaining that he was from Iowa. “Forrest said what in hell are you down here for? I have a great mind to have you killed for being down here. He then said if the North west had staid home the war would have been over long ago,” before ordering a guard for the surgeon’s protection.

Fitch subsequently added that “Forrest was up there [on the bluff], sighting a piece of artillery on the little gunboat up the river. I do not think Forrest knew what was going on under the bluff.” Concerning Chalmers, Fitch concluded, “I have always thought that neither you nor Forrest knew anything that was going on at the time under the bluffs. What was done was done very quickly.”

Union Capt. John Woodruff reported that Chalmers had conceded to him “that the men of General Forrest’s command had such hatred toward the armed negro that they could not be restrained from killing the negroes after they had captured them. He said they were not killed by General Forrest’s or [Chalmers’] orders, but that both Forrest and he stopped the massacre as soon as they were able to do so.” Nevertheless, Chalmers concluded as Forrest had, “it was nothing better than we could expect so long as we persisted in arming the negro.”

Forrest himself wrote to Union Gen. Cadwallader C. Washburn in the summer of 1864 that “I regard captured negroes as I do other captured property, and not as captured soldiers.….You ask me to state whether ‘I contemplate either their slaughter or their return to slavery.’ I answer that I slaughter no man except in open warfare, and that my prisoners, both white and black, are turned over to my Government to be dealt with as it may direct.” Forrest’s interpretation of Confederate policy toward captured African-American troops was self-serving, but his aide, David C. Kelley, noted that the general “was opposed to the killing of negro troops; that it was his policy to capture all he could and return them to their owners.” In fact, Forrest had ordered such a disposition for some of his black prisoners from the fort.

Racial animus was clearly a factor in the Fort Pillow killings, given that black troops comprised the largest proportion of the fort’s defenders who died in the engagement or its aftermath. Sectional antipathy, panic and chaos, ineffective leadership and faulty decision-making by the Union commander, wartime political and election year imperatives, recrimination and ultimately reconciliation also factored into the actions and assessments that comprised the Fort Pillow “massacre.” As such, Fort Pillow fit into patterns of behavior in warfare that occurred before and after 1864 and elsewhere in that bloody year of the conflict. Yet, the Forrest who would never be known for employing half measures did not supervise the killing personally to ensure that his men wiped out the defenders completely, had that outcome been his intent. Even so, accusations that “that devil Forrest,” as William T. Sherman once called him, deliberately attempted to annihilate the garrison at Fort Pillow continued to dog him.

Reports of excesses associated with Forrest did not end at Fort Pillow. After the fall of Selma, Ala., to Union Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson’s powerful advance, Forrest and members of his personal escort approached an isolated Union outpost manned by members of the 4th U.S. Cavalry. The Confederates held members of this unit responsible for misdeeds attributed to them, and a wounded and exhausted Forrest allowed the men to proceed in their attack without his direct leadership. After an “animated fight” the Confederates counted 35 killed or wounded and five prisoners among the Federals, while suffering the loss of only one man wounded, although the officer who led the assault in Forrest’s stead maintained that “not a single man was killed after he surrendered.”

But a Union account of the matter concluded that Forrest and his men “came across a party of Federals asleep in a neighboring field, and charged on them, and, refusing to listen to their cries for surrender, killed or wounded the entire party, numbering 25 men.” Sergeant James Larson of the 4th labeled the incident a “repitition [sic] of Ft. Pillow.” In memoirs that appeared years later, Wilson observed that the Confederates had “killed the last one of them,” and concluded, “Such incidents as this were far too frequent with Forrest.” Wilson maintained that his opponent’s “ruthless temper…impelled him upon every occasion where he had a clear advantage to push his success to a bloody end, and yet he always seemed not only to resent but to have a plausible excuse for the cruel excesses that were charged against him.”

Following the surrender of his command in May 1865 at Gainesville, Ala., Forrest attempted to restore his reputation. While to some he became a model of reconciliation, to others he remained the “Butcher of Fort Pillow.” Seeking a pardon from President Andrew Johnson, Forrest acknowledged that he continued to be “regarded in large communities, at the North, with abhorrence, as a detestable monster, ruthless and swift to take life.” But he offered “to waive all immunity from investigation into my conduct at Fort Pillow.” His association with the Ku Klux Klan, including serving as its first “Grand Wizard,” also worked against him in many circles and followed him until his death on October 29, 1877.

Brian Steel Wills, director of the Center for the Study of the Civil War Era and professor of history at Kennesaw State University in Kennesaw, Ga., is the author of a number of Civil War histories, including The River was Dyed with Blood (University of Oklahoma Press, 2014).

Originally published in the March 2014 issue of America’s Civil War.