For more than a century, the fighting that occurred in and around John Kuhn’s brickyard was most often a mere footnote in the history of the July 1863 Battle of Gettysburg. Two highly regarded 20th-century histories offer telling examples. General Edward J. Stackpole made no mention of the so-called Brickyard Fight in his popular 1956 book They Met at Gettysburg, and Edwin B. Coddington devoted only two sentences to it in his classic 1968 account, The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command. And so it went, year after year, in book after book about the most chronicled battle in American history.

Why exactly has the Brickyard Fight—which resulted in more than 770 Union and Confederate casualties—been neglected for so long in histories of the battle? The answer is twofold.

First, the action took place on the afternoon of July 1. Historians and popular memory have traditionally devoted more attention to the battle’s second and third days at the expense of the first. The July 1 battle has frequently been depicted as a prelude to more important events, an engagement that involved only portions of the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia, whereas both armies were present in full on the next two days. The first day was also a clear Confederate victory, which contrasted with the Union successes on the second and third days. In addition, the July 1 fighting occurred on grounds remote from the rest of the battlefield, with landmarks that received less attention than the famous sites of the second and third days. Likewise, the most memorable images captured by the photographers who visited Gettysburg in the aftermath of the battle—most notably depictions of the dead—were taken on the southern portion of the battlefield.

As the first day was seen as subordinate to the other two days, so too was the fighting in Kuhn’s brickyard considered by many an inconsequential rearguard action at the end of a long day of more significant combat. It involved only a single Union brigade and two Confederate brigades, unlike the many brigades and divisions of several corps that fought elsewhere on July 1. And perhaps most significant, no after-action reports by the Union brigade and regimental commanders were included in the massive Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, leaving their story untold and denying historians significant resources needed to tell it.

A key debate surrounds the engagement, however: Could the Confederates, after driving the Union troops from the brickyard and elsewhere through the town of Gettysburg to Cemetery Hill, have pressed their advantage and taken the hill the evening of July 1, thereby depriving the Union army of the high ground it successfully defended the next two days? No doubt, by slowing the attack of two of the last fresh Confederate brigades in the Brickyard Fight, a single Union brigade bought time for other Federal units to make good their escape to the shelter of Cemetery Hill, consequently making a late-afternoon Confederate assault on the hill more unlikely.

The True Price of War

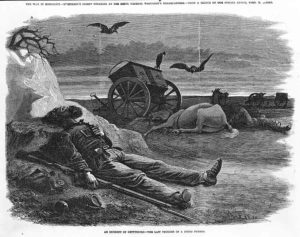

A particular Brickyard Fight combatant would become not only one of the battle’s most recognized casualties but also of the entire Civil War. After the respective armies left Gettysburg, the corpse of a Union soldier was found on Judge Samuel R. Russell’s property, not far from the brickyard. There was nothing on the dead man’s body to identify him, but clutched in his hand was an ambrotype of three children. John Francis Bourns, a Philadelphia physician in Gettysburg to help tend the wounded, realized the photograph was a single sad clue to the identity of the devoted father and his family. Back in Philadelphia, Bourns used the ambrotype to initiate a publicity campaign to discover just who the unknown soldier was. A month after the story first appeared in a newspaper, the corpse was identified as Sergeant Amos Humiston of the 154th New York, whose wife, Philinda, and three children—Frank, Alice, and Fred—lived in Portville, N.Y.

The touching incident soon inspired a flood of prose, poetry, and song commemorating Sergeant Humiston and his “Children of the Battle Field.” After the war ended, Bourns led a drive to establish a soldiers’ orphans’ home in Gettysburg, which was opened on Cemetery Hill in 1866 with Humiston’s widow and orphans among the first residents. –M.H.D.

The Brickyard Fight is also worth remembering for the human cost. It was not a peripheral skirmish with few casualties on the fringe of the battle, but a hard-fought action that cost the Union troops dearly in soldiers killed, wounded, and captured—with one regiment, the 154th New York, suffering one of the highest casualty rates (77 percent) endured during the war. And a particular casualty of the fighting there, Sergeant Amos Humiston of the 154th New York (see sidebar, below) became the subject of one of the most unforgettable human-interest stories to emerge from the battle and the Civil War as a whole. John Kuhn’s brickyard was situated on North Stratton Street in the northeastern outskirts of Gettysburg. Kuhn’s two-story brick house (today 221 North Stratton Street) faced the street. Beside it was a carriage gateway that provided access to a five-acre pentagonal lot, which was enclosed by sturdy rail fences. Small portions of the yard near the house were fenced off for livestock and a garden. Behind stood the brickworks—a wooden barn, dome-shaped brick kilns, and a pug mill. A small stream, Stevens Run, traversed the southeastern portion of the yard, providing a plentiful and convenient source of water.

Kuhn, his wife, five children, and two teenaged boys—perhaps apprentice brick makers—occupied the house, built in the spring of 1860. The neighborhood continued to expand that year, spurred at least in part by the availability of Kuhn’s bricks, but the cluster of houses still occupied a largely rural landscape apart from the main town. On the slope to the north of the brickyard, and in the flats to the east and south, wheat fields ripened in the summer heat.

Could the Confederates have pressed their advantage and taken Cemetery Hill on July 1, thereby depriving the Union Army of the high ground?

It was upon this bucolic and peaceful tapestry that the sun rose on July 1, 1863. By nightfall, the neighborhood had been transformed by the ravages of war. The soldiers of Union Colonel Charles R. Coster’s 1st Brigade awoke early that morning at their camps near the old convent at Emmitsburg, Md., about 11 miles south of Gettysburg. For the previous three weeks, since leaving their camps in Stafford County, Va., the men had alternated grueling, hot, dusty marches with welcome periods of rest. On entering Maryland, they were delighted to receive a warm welcome from Union sympathizers along their path, who plied them with food. When they arrived at the Emmitsburg convent—which had been founded decades before by Elizabeth Ann Seton, now a Roman Catholic saint—the nuns served them soft bread and sweet milk.

Coster’s brigade belonged to Brig. Gen. Adolph von Steinwehr’s 2nd Division in Maj. Gen. O.O. Howard’s 11th Corps. The unit consisted of four volunteer infantry regiments: The 27th Pennsylvania, composed almost exclusively of Germans from Philadelphia and commanded by Lt. Col. Lorenz Cantador; the 73rd Pennsylvania, another largely German outfit from Philadelphia, commanded by Captain Daniel F. Kelly; the 134th New York, raised mainly in Schoharie and Schenectady counties and commanded by Lt. Col. Allan H. Jackson; and the 154th New York, recruited in Cattaraugus and Chautauqua counties and commanded by Lt. Col. Daniel B. Allen.

From Cemetery Hill they could see billowing clouds of gun smoke to the north. a battle was raging, and they were soon to be thrust into it.

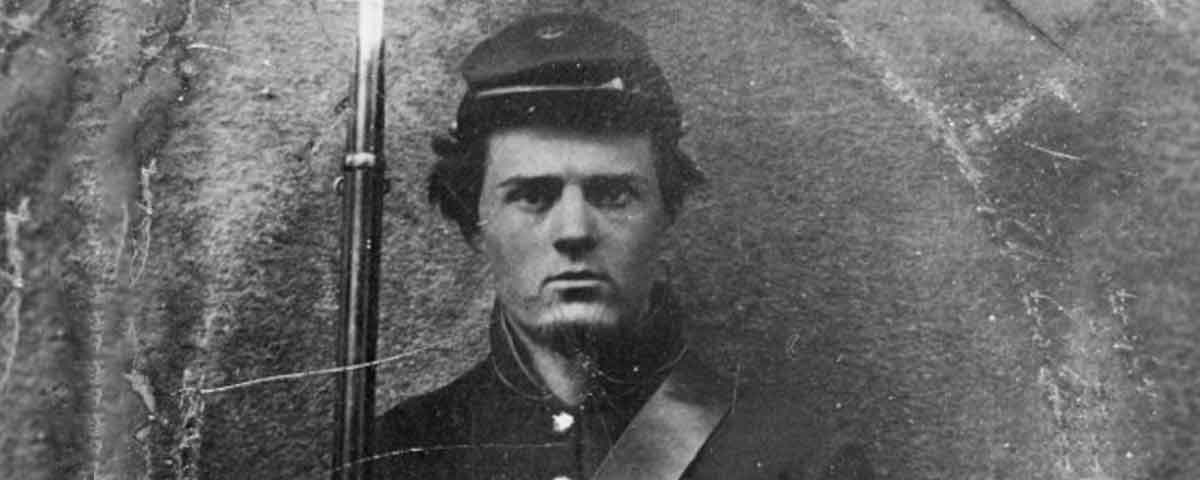

The 23-year-old Coster had joined the brigade less than two months before, in mid-May, when his regiment, the 134th New York, was transferred from the 2nd Brigade to the 1st. He assumed command of the brigade by seniority on June 1 when its long-time commander, Colonel Adolphus Buschbeck, departed on a leave of absence. A native of New York City, Coster had served briefly as a private in the 7th New York State Militia before becoming a first lieutenant in the 12th U.S. Infantry. He was wounded at the Battle of Gaines Mill during the Peninsula Campaign, after which he was commended for bravery and promoted to captain. When he was commissioned colonel of the 134th New York in October 1862, the regiment’s rank and file initially dismissed him as a “Fifth Avenue big bug,” but he soon earned their admiration and respect. As a brigade commander, however, Coster was not well known to his three other regiments—and he was untried.

Morale and esprit de corps were weak in the 1st Brigade. Under Buschbeck, it had made a gallant but brief and futile stand in opposing Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s epic flank attack at Chancellorsville back in May. The resulting high casualty count and Union defeat in that battle had depressed spirits among the men. The rest of the army and the Northern public at large had heaped derision and calumny on the 11th Corps for the rout at Jackson’s hands. Ethnic animosity worsened the situation. The large numbers of German-Americans in the corps were the targets of prejudice from within the army and without, and ethnic tensions simmered between the 1st Brigade’s largely native-born American New York regiments and the “damned Dutchmen” from Pennsylvania.

On the morning of July 1, Coster’s brigade was weakened when 50 men from each of the four regiments were ordered to make a reconnaissance to Sabillasville, Md., about six miles west of Emmitsburg. Under the command of Major Lewis D. Warner of the 154th New York, the 200 men left at 5 a.m., unaware of their fortune in drawing the assignment. Coster now had 1,259 men at his disposal.

The 1st Brigade left Emmitsburg about 8 a.m. under scattered showers that gradually gave way on a gentle southerly breeze to a humid, sunlit day. Leaving their knapsacks and baggage behind but retaining their haversacks, the men marched north on the Emmitsburg Road, crossed into Pennsylvania, and eventually followed the Taneytown Road north to Gettysburg. The infantry kept to the fields to allow the artillery and ammunition trains to hurry forward on the muddy and stony roads.

When the brigade crossed Marsh Creek about five miles south of Gettysburg, it came within earshot of the rattle and roar of musketry and cannon fire. When orders came to hurry the 11th Corps to Gettysburg, the men rushed forward on the double-quick. The 1st Brigade arrived about 3 p.m. Coster placed his two New York regiments along the Baltimore Pike on the northeast end of Cemetery Hill, in and around Evergreen Cemetery, in support of Captain Michael Wiedrich’s Battery I, 1st New York Light Artillery. The 73rd Pennsylvania was deployed as skirmishers at the base of the hill, while the 27th Pennsylvania was pushed farther into the town to occupy buildings along High Street.

“The Disability is Permanent”

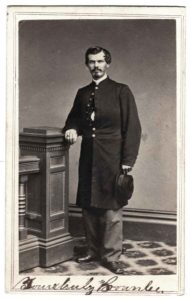

Despite receiving seven wounds in a matter of minutes during the brickyard fighting, including getting struck by an 18-inch piece of railroad iron fired from a Confederate cannon, Private James Brownlee of the 134th New York survived the Civil War and lived another 41 years. Serious wounds, however, to his bladder, sternum, and right lung incapacitated him for life. He spent extended recovery periods at Gettysburg’s Camp Letterman and then hospitals in New York City and Albany. In 1867, one of his doctors reported: “The right lung is almost totally useless. I can detect no respiratory murmur, and he has a cough and feeble pulse. In my opinion, the disability is permanent.” Brownlee was 62 when he died from a stroke in 1904.

From Cemetery Hill they could see billowing clouds of gun smoke to the north, beyond the town’s spires and rooftops, marking the lines of contending troops. A battle was raging, and they were soon to be thrust into it. Their opponents would be part of Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s Division of Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s Second Corps, which had marched 12 miles south that day from Heidlersburg to reach the battlefield about 3 p.m.

Early’s Division consisted of a brigade of three Virginia regiments commanded by Brig. Gen. William Smith; a brigade of six Georgia regiments commanded by Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon; and the two brigades that would engage in the Brickyard Fight: the Louisiana Tigers of Brig. Gen. Harry Thompson Hays and Brig. Gen. Robert F. Hoke’s North Carolina Brigade, under the command of Colonel Isaac Erwin Avery while Hoke recovered from wounds suffered at Chancellorsville. Confident, cocky, battle-hardened veterans filled both Hays’ and Avery’s brigades.

The previous month, Early’s Division had left its camps near Fredericksburg, Va., and proceeded via Culpeper, Winchester, and Martinsburg to Shepherdstown. After crossing the Potomac River and traversing Maryland to the west of South Mountain, the Confederate contingent entered Pennsylvania, headed for York, whose mayor surrendered the city on June 28. Early was preparing for a strike on Harrisburg, but on June 29 he received an order from Ewell to reverse course. During a midday lull in the fighting July 1, the Union 11th Corps reached Gettysburg, and Howard took command by seniority of the combined Union forces on the field. Major General Carl Schurz in turn assumed control of the corps and moved its 1st and 3rd Divisions through the town to the plains to its north, where they formed to the right of the 1st Corps. The 2nd Division, consisting of Coster’s 1st Brigade and Colonel Orland Smith’s 2nd Brigade, was held in reserve on Cemetery Hill.

The thin line of the 11th Corps stretched all the way from the vicinity of the Mummasburg Road northwest of Gettysburg, where it failed to connect securely to the 1st Corps’ line and veered from it at a right angle, across the Carlisle Road to Blocher’s Knoll and the Harrisburg Road—its right flank exposed and unprotected. In the coming fight, the two 11th Corps divisions would be roughly equal in numbers with their Confederate foes, but they were hampered by two distinct disadvantages. First, they were poorly positioned on generally flat terrain that offered no defensive protection. Second, the elevation of Generals Howard and Schurz had caused a ripple effect among underlings, giving new assignments to officers as a grave crisis loomed. As historian Harry Pfanz noted in analyzing the situation the 11th Corps faced that day: “In retrospect, the result seems preordained.”

Wounded Union soldiers lined the sidewalks, some crawling on their hands and knees, others seeking shelter between buildings and in alleys.

Ewell’s Corps had two brigades of Georgians: Gordon’s of Early’s Division and Brig. Gen. George Doles’ Brigade of Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes’ Division. Doles’ Brigade struck the 11th Corps line in the vicinity of the Carlisle Road and sent two brigades of Yankees reeling in retreat toward the town. Meanwhile, Gordon’s Brigade rushed to attack the exposed Union right flank on Blocher’s Knoll and after some bitter fighting drove the other two 11th Corps brigades toward Gettysburg as well. At about the same time, Hill’s forces were driving the 1st Corps from its positions west of Gettysburg back into the town.

When Schurz deployed the 11th Corps, he asked Howard for reinforcements to bolster his lines. Howard refused, until given no choice but to relent when Gordon’s Georgians threatened the corps’ right flank at Blocher’s Knoll. Coster’s brigade was now being sent to Schurz’s aid.

Coster’s men headed down Baltimore Street into Gettysburg at a quickstep, with the 134th New York in the lead, followed by the 154th New York. They were soon joined by the two Pennsylvania regiments. It certainly didn’t help that the sidewalks were lined with wounded Union soldiers, some crawling on their hands and knees, others seeking shelter between buildings and in alleys, others carried by comrades to the rear. Cavalrymen clung to wounded horses.

At some point during the march, however, a decision was made to place the 73rd Pennsylvania in reserve near the town’s railroad station, leaving Coster with about 977 men. His three remaining regiments crossed the railroad tracks and then Stevens Run on a stone bridge to reach the brickyard. As they arrived, a cannonball struck the corner of Kuhn’s house and sent a shower of bricks flying, striking a member of the 154th. The 134th formed the brigade’s right flank, and the 154th the center, aligned along the fence marking the brickyard’s northern boundary, in front of the brick kilns. Coster was with the 27th Pennsylvania, which formed on the left, where he could look down the slope and see his two New York regiments. Noticing a gap between the 134th and 154th, Lt. Col. Cantador ordered a battalion of the 27th to plug it, but in the noise and chaos, only 50 men under 1st Lt. Adolphus D. Vogelbach complied.

The brigade’s position was perilously poor. Both flanks were unsupported and in danger of envelopment. The terrain was disadvantageous. To the north of the brickyard the ground rose abruptly, which hindered sight in the direction from which the enemy would be coming. It didn’t help that the hillock was covered in wheat ready for harvesting. By the time they were seen by the 154th, the Rebels were only 220 yards away.

Vindication of a Valiant Struggle

In 1864 the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association was formed. It would be responsible for the postwar purchase and preservation of battlefield acreage, a network of roads linking various sites, and placement of markers specifying the positions of the troops. Among the sites purchased was one less than three-quarters of an acre running from North Stratton Street along the northern edge of Kuhn’s Brickyard, following the lines of the 27th Pennsylvania and 154th New York. It was named Coster Avenue.

Meanwhile, state commissions funded monuments to the various regiments that fought at Gettysburg. After New York State erected the 21-foot-tall monument to the 154th New York on Coster Avenue, a party of regimental veterans and their families and friends dedicated it on July 1, 1890—the Brickyard Fight’s 27th anniversary. For years thereafter, veterans of the regiment made pilgrimages to the monument.

Because Coster Avenue did not include all the ground held by Colonel Charles R. Coster’s brigade during the battle, New York State erected a monument to the 134th on East Cemetery Hill (dedicated in 1888), while a bronze marker at Coster Avenue describes the regiment’s position during the Brickyard Fight. Another bronze marker at Coster Avenue describes the brigade’s action as a whole. In 1884, 27th Pennsylvania veterans erected a small white marble monument on East Cemetery Hill, and when the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania placed a larger memorial there in 1889, the marble monument was moved to Coster Avenue.

Since 1895, Gettysburg National Military Park has maintained Coster Avenue. The former brickyard and adjoining fields soon gave way to the streets, homes, and businesses that surround the site today. By the centennial, residents tended to ignore the markers and monuments and used it as a playground, football field, and dog park.

In June 1963, just before the Brickyard Fight’s 100th anniversary, NBC TV’s “David Brinkley’s Journal” used imagery of Coster Avenue to illustrate the encroachment of private structures on the battlefield. Isolated from major portions of the battlefield, tucked away in town off a side street, Coster Avenue was well off the beaten track for most of the hundreds of thousands of annual visitors to Gettysburg. Fortunately, that isn’t true today. –M.H.D.

In the wake of Confederate successes on Blocher’s Knoll, Early had ordered Hays’ and Avery’s brigades forward between about 3:45 and 4 p.m. Wild with excitement, they drove off a few companies of isolated Union skirmishers, crossed a series of fences, and splashed across Rock Creek, coming within sight of Coster’s position in the brickyard. Positioned near the Carlisle Road, to Coster’s left, were the four Napoleons of Captain Lewis Heckman’s Battery K, 1st Ohio Light Artillery. The Yankee gunners began firing at the advancing Confederates, who soon broke into the double-quick.

Their battle flags bobbing, the North Carolinians and Louisianans—about 3,000 total—advanced in splendid style until a volley from the brickyard stopped them. They immediately returned the fire and the battle became general. The Federals were kneeling or lying behind the thin shelter of the rail fence, built on a low embankment, and immediately began to suffer casualties.

Under the circumstances, Coster’s stand in the brickyard was inevitably brief. Members of the 154th had time to fire only six to nine shots apiece. Avery’s men swung around the right flank of the 134th and unleashed a murderous enfilading fire. With his regiment badly shot up and in danger of being surrounded, Lt. Col. Jackson ordered the 134th to retreat. Many of the men were struck down as they left the cover of Kuhn’s fence. They fled the brickyard and darted through fields and lots toward the railroad and the town and Cemetery Hill beyond. On the Union left, the Tigers sent the 27th Pennsylvania and Coster reeling in retreat, pouring into the large gap between the 27th and Heckman’s battery. Heckman’s gunners would fire 113 rounds (an average of 28 per gun), mostly canister, over a period of about a half-hour before the battery was overrun. Two guns were captured.

Their battle flags bobbing, the North Carolinians and Louisianans—about 3,000 total—advanced in splendid style.

At first only the 27th Pennsylvania heard Coster’s order to retreat, but when Lt. Col. Allen of the 154th saw the 134th driven from the brickyard, he ordered a retreat to the left, toward the carriage gateway and North Stratton Street, accompanied by Vogelbach’s squad. The lots and fields beyond were swarming with Hays’ exultant Confederates, however, and Avery’s men quickly clambered over the fence into the brickyard, forcing a mass surrender.

In attempting to evade capture, some of Coster’s men hid in area houses. Some crowded into the cellar of John Kuhn’s home, where they were easily captured. (Kuhn’s house became a temporary hospital, although the night of July 2, the wounded Confederates were moved elsewhere, leaving only the Union wounded there.) A woman hid a sergeant of the 134th New York and three of his comrades in her home in town. Lieutenant Colonel Allan Jackson of the 134th and a private of his regiment hid in a loft above the kitchen in the home of Mrs. Henry Meals on York Street. Two days later, the two men set out in disguise and made it through the Confederate lines to rejoin their regiment on Cemetery Hill. After driving Coster’s men from the brickyard, Hays’ Brigade continued the pursuit into the town, shooting and capturing more Yankees. Avery’s Brigade, which had suffered more casualties and become disorganized by the melee, halted to regroup and watch over the hundreds of prisoners. When the 134th New York reassembled on Cemetery Hill that afternoon, it numbered only five officers and 27 enlisted men. For the 154th New York, only three officers and 15 enlisted men remained. That evening and through the night a number of stragglers found their way to their regiments. The exhausted men slept among the headstones in Evergreen Cemetery.

The next morning, Major Lewis Warner and his detachment reached Cemetery Hill, raising the 154th’s total to about 75 men. The regiment was temporarily consolidated with the 134th under the command of Lt. Col. Allen and then Lt. Col. Jackson, following his daring run through Gettysburg while in disguise. About a quarter of Coster’s brigade was killed or wounded in the Brickyard Fight, with the 134th New York incurring 252 total casualties and the 154th 207. As mentioned earlier, the 154th’s 77 percent casualty rate was one of the highest regimental loss ratios in the battle and indeed the war.

Confederate losses stood at 208 total. The 6th North Carolina suffered the highest toll for Avery, with 84 killed or wounded. In Hays’ Brigade, 22 of 63 total casualties were in the 8th Louisiana. Ironically, Hays had 15 men captured.

Coster’s diminished command met Hays’ and Avery’s forces a second time, during the July 2 night attack on East Cemetery Hill. The Confederates broke the Union line at the foot of the hill and were fighting for the guns of Wiedrich’s battery at its crest when Coster’s men were rushed to the scene. The 73rd Pennsylvania, held in reserve the previous day, led the brigade, and with the 27th Pennsylvania helped to drive the Confederates from the embattled artillerymen and down the hill. The results were the opposite of the prior day’s Brickyard Fight. Coster had the support of other units and his men gained some revenge with a successful charge that cost them only 30 casualties.

About a quarter of Coster’s brigade was killed or wounded in the Brickyard Fight, with the 154th New York incurring a 77 percent casualty rate—one of the highest regimental loss ratios in the war.

The Confederates suffered much greater losses and reeled in a chaotic retreat, leaving a number of prisoners of war. Hays lost 250 men and Avery was mortally wounded, one of 200 losses in his brigade. Colonel Archibald Godwin of the 57th North Carolina succeeded Avery as brigade commander.

On July 3, Hays’ and Godwin’s weary and battered men had a badly needed rest in the streets of Gettysburg. On Cemetery Hill, Coster’s brigade, in line along the Taneytown Road, endured fire from Confederate batteries and sharpshooters with little harm and witnessed the Confederates’ doomed Pickett’s Charge against the center of the Union line. The Army of Northern Virginia evacuated Gettysburg that night.

On July 4, Coster’s brigade marched into town. His men were posted throughout the borough to help in barricading the streets. They also returned to the brickyard neighborhood to gather and bury their dead comrades. They identified those they could, although as Major Warner noted, many were “so swollen and disfigured that recognition was impossible.” During the stay in town, several men who had been missing and in hiding since July 1 rejoined the brigade.

On July 5, with the Army of Northern Virginia retreating back to Virginia, Coster’s brigade left Cemetery Hill in pursuit.

Adapted with permission from Gettysburg’s Coster Avenue: The Brickyard Fight and the Mural, by Mark H. Dunkelman (Gettysburg Publishing, 2018).