Donald Trump’s campaign has transformed the Republican Party, as its beaten establishment knows: the Grand Old Party’s last two presidents, Bushes 41 and 43, and most recent nominee, Mitt Romney, have refused to endorse Trump. Could a GOP loss in November destroy the party? South Carolina Senator Lindsay Graham, before backing the billionaire, said, “I have never been more worried about the Republican Party breaking apart.” Rolling Stone correspondent Matt Taibbi was more blunt: Republicans, he wrote, are “doomed to go the way of the Whigs.”

For 20 years, the Whigs were half of our two-party system, electing two presidents and numerous congressmen and governors and enjoying the support of almost half the voters. What killed the Whigs? Could particide happen again?

America’s close-enough victory in the War of 1812 melted political divisions into the Era of Good Feeling—until 1824, when James Monroe, the last founder president, retired, setting off a scramble for the White House.

Eventual winner Andrew Jackson became the leader and catalyst of the new Democratic Party. With gloves-off populist style, he stood for the common man, opposed a national bank, and favored states’ rights. A war hero and duelist, Jackson the president fought with his Cabinet, ignored Supreme Court decisions he didn’t like, and threatened to send federal troops when South Carolina pushed states’ rights further than he liked. Rivals began thinking of him as a would-be king, with themselves the patriotic opposition. In 1834, Kentucky Senator Henry Clay reached into English history for the anti-royalist label “Whig.” A new party was born, and named.

The new Whigs attracted businessmen. Clay praised factory owners as “enterprising, self-made men, who have acquired whatever wealth they possess by patient and diligent labor.” Given a religious spin, these traits fit well into the Second Great Awakening, the revival that swept Protestant congregations in the 1830s; evangelicals became a Whig constituency. Whiggery tended to be strongest in New England and among New Englanders relocating to the Midwest, though the party also did well in Southern cities. This forced Whigs to straddle questions concerning slavery, but in the 1830s and ’40s these were not yet front and center.

Populism, with its rough-and-tumble, irked Whigs, who were law-abiding and buttoned-up. The party supported voter registration laws to combat Democratic skill at ballot-box stuffing and deplored mob violence. In his first important speech, as a young Whig, Abraham Lincoln condemned lynchings in Mississippi, Missouri, and Illinois.

Whigs and Democrats differed in substance as well. Democrats believed in laissez-faire economics. Whigs wanted a federal road- and canal-building program to link resources and markets and tariffs to encourage domestic production. Democrats thought the Second Bank of the United States the tool of an economic elite; Jackson killed that institution, refusing in 1836 to renew its charter. Whigs valued the bank’s power over credit as a way to keep local banks honest and hoped to revive it. Democrats loved the little guy, if he was white. Whigs, at least in the north, were mildly pro-black, a stance that black voters rewarded where they were allowed to vote. Democrats were Anglophobes—Jackson had killed a lot of Brits at New Orleans. When in power, the Whigs negotiated a settlement with Britain of the U.S.-Canada border.

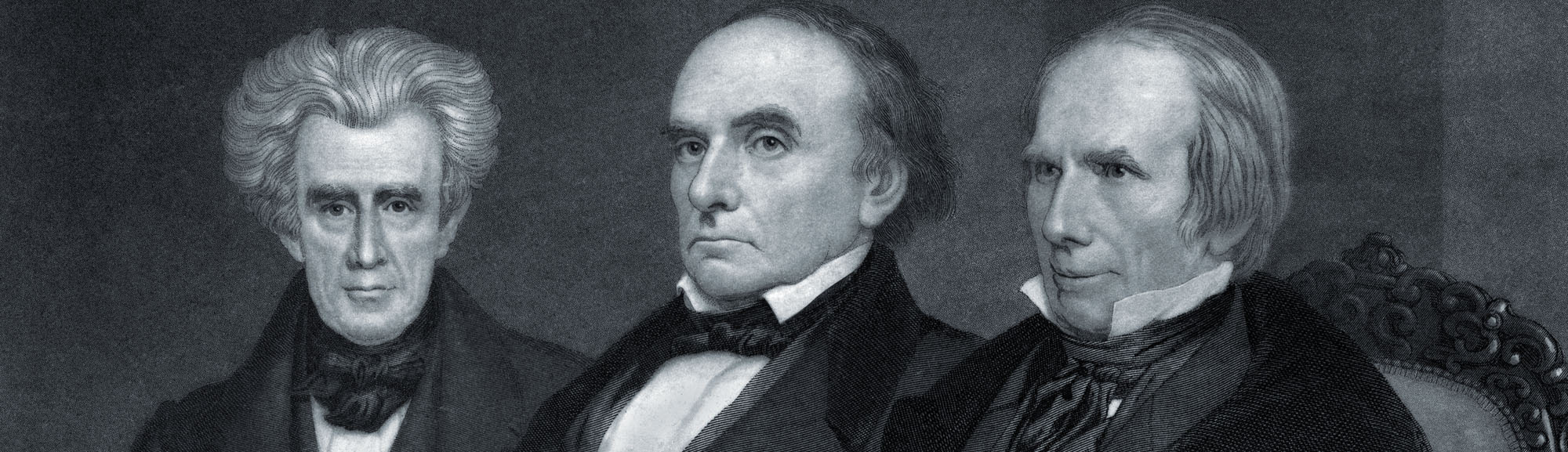

Before electronic media, entertainment was oral—sermons, plays, speeches. America’s greatest orators were two Whig titans of the Senate, Clay and Daniel Webster. When either spoke, it was showtime. Clay addressed audiences “very much as an ardent lover speaks to his sweetheart,” wrote a rapt spectator. “His voice was full, rich, clear, sweet, musical, and as inspiring as a trumpet.” Webster was almost frighteningly overpowering. England’s Thomas Carlyle wrote of his “dull black eyes under the precipice of brows like dull anthracite furnaces needing only to be blown.” Both were ever scheming, unsuccessfully, to become president.

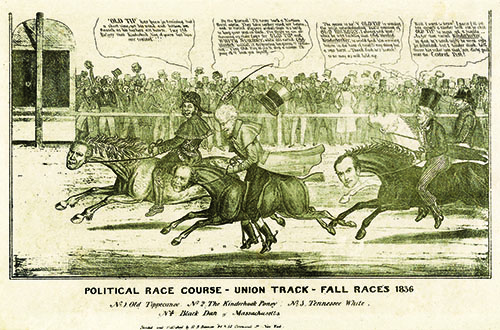

In a debut presidential outing in 1836, the Whigs ran four regional candidates—Webster in Massachusetts, Willie Person Mangum in South Carolina, Hugh White in the rest of the South, and everywhere else William Henry Harrison—hoping to throw the contest to the House of Representatives.

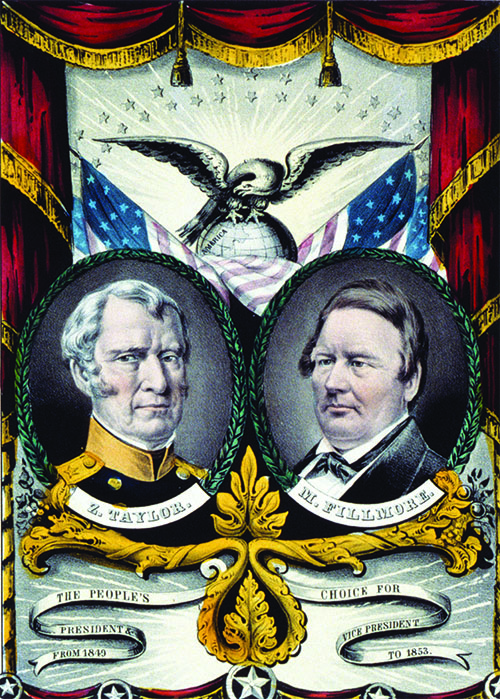

This elaborate plan failed when Jackson’s heir, Martin Van Buren, won a clean majority. The Panic of 1837, triggered by the Democrats’ war on the bank, crippled Van Buren and paved the way for a smashing victory in 1840 for Harrison, whose running mate, John Tyler, was a states’ rights Southerner on the ticket for regional balance. After only a month in the White House, poor Harrison died of pneumonia, elevating Tyler. The election of 1844 was a nail-biter: Whig Clay narrowly lost New York, and the Electoral College, to Democrat James Polk. The Whigs rebounded in 1848 under Zachary Taylor, a hero of the Mexican War. But Taylor too died in office. In 1852, the party put up another general, Winfield Scott; Democrat Franklin Pierce decisively beat him.

Winning two of five presidential elections is not a bad record, but that box score conceals serious problems. The first arose in April 1841 with Harrison’s death. Harrison, who had Whig majorities in both houses of Congress, had planned to charter a new Bank of the United States. But at every turn, inheritor Tyler blocked the party that had gotten him into the White House. There would be no Bank of the United States until the Federal Reserve in the 20th century.

The second problem was the Mexican War. Whigs preferred developing the American economy to carving into Mexico; they also feared that annexing Texas and the Southwest would stir a crisis over extending slavery. That is exactly what happened.

Clay’s last great senatorial act, supported by Webster, was the Compromise of 1850, admitting California as a free state in exchange for perks given the South. Clay and Webster both died in 1852. Two years later, Democrat Stephen Douglas ignited a new firestorm, proposing a bill to allow slavery in the Kansas-Nebraska territory, if inhabitants wanted it.

As long as slavery was off the table, Northern and Southern Whigs had been able to work together, but with bondage in its face, the party dissolved. Many northern Whigs, like Abraham Lincoln, became Republicans; Southerners joined the Democrats. Whigs disdaining either option gravitated to minor outfits like the Know-Nothings and the Constitutional Union Party, which ran former Whigs for president—Millard Fillmore in 1856, John Bell in 1860—in vain. The Civil War destroyed Whiggery and reset politics for 100 years.

The most famous Whigs never reached the White House, and the lesser known Whigs who did could not reanimate their party’s economic centerpiece, the Bank of the United States. But the party’s demise required an issue—slavery—explosive enough to threaten the entire country’s existence.

Obituaries for the GOP are premature. Donald Trump, win or lose, is a new element in the political firmament. But none of Trump’s concerns—trade, immigration, Hillary Clinton’s probity—risks sundering the country. Our two major parties are old, big, rich, and, for all their stodginess, cunning enough to weather ordinary crises. In the past they have done so by changing principles, leaders, and constituencies, and they can do so again. Absent a national near-death experience, they won’t.