The author, who spent almost four years as a prisoner of the Japanese in World War II, asks a question that may have only partial answers: Why do men survive?

When you visit our comrades’ honored graves

(Mists crowding in, quietly comes dawn in the forest)

The railbed grows chilly and mists penetrate your body.

—A song of Japanese engineers

SOMETIME IN THE 1920s THE BRITISH had envisaged linking the Thai and Burmese rail systems. The idea was never pursued. The terrain was mountainous. Numerous rivers and streams would require bridging. And in a jungle whose impenetrability is second only to the Brazilian rainforest, the maintenance of a large work force was problematic: The region is host not only to the usual tropical diseases, but to cholera and a fatal strain of cerebral malaria.

In 1939 the Japanese, too, looked at the feasibility of a similar rail link. They understood that in the event of war, if ever they failed to control the Bay of Bengal and were denied access to the port of Rangoon, they would have to convey troops and matériel overland from Bangkok. The civilian engineer appointed by Army General Headquarters in Tokyo reported that two years were needed to complete the project. This estimate was confirmed by a clandestine reconnaissance party sent in August 1941, five months before the Japanese invasion of Thailand and Burma.

The destruction of the Japanese carriers at Midway brought about the dreaded eventuality: the loss of the Indian Ocean to the Royal Navy’s Far East Squadron. The building of the Thai-Burma railway link had suddenly become an imperative. Unless it was operative in a year, the invasion of India would have to be scrapped.

In April 1943, 7,000 British and Australian POWs, designated as F Force, shipped out of Changi, the vast prewar barrack compound at the tip of Singapore Island, where the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) had herded the defeated Allied troops after the capture of the city. Group after group had been shipped north to the railway, and F Force was one of the last to leave. It was earmarked for the work camps beyond the upper reaches of the Mae Nam Kwae Noi (or, as the movie popularized it, the River Kwai), south of the Three-Pagoda Pass, where three Buddhist structures marked the highest point of the Thai rail line near the border with Burma.

F Force suffered greater losses than any other group for two main reasons: the remoteness of the camps, which made access to food supplies problematic soon after the monsoon’s onset; and the composition of the force itself, a third of which was made up of prisoners officially designated sick by the Japanese themselves.

A less obvious factor was that F Force was “loaned ” by the Malaya POW Administration to the two IJA engineer regiments responsible for the “Death Railway,” as it came to be known. Since F Force, unlike other groups, was not officially incorporated into their work units, they neither “owned” it nor felt responsible for its welfare. The engineers treated F Force as if it were expendable, as expendable in fact as the cooties.

—J.S.

I WAS DETAILED TO ACCOMPANY F FORCE as an interpreter. I was bilingual in French, had been taught bazaar Arabic, and was due to serve in counterintelligence in the Middle East. The randomness of war, however, landed me in Singapore in January 1942, and a month later I’d become, as we used to put it, a guest of His Imperial Majesty. My commanding officer encouraged me to learn Japanese. It took six months of tutoring and study to become proficient enough to be included in the tiny roster of official interpreters, most of them sons of missionaries once stationed in Japan.

With the survivors of F Force, I was shipped back to Singapore when the “loan” to the engineers came to an end, nine months after our departure. But during that terrible year of 1943, to the cry of “Speedo!” 150,000 men—prisoners and Asiatic levies—perished building 350 miles of railway line that never served its intended purpose. No sooner was it completed than the Royal Air Force and the U.S. Air Force reduced its operational capabilities by two-thirds.

In Kranji, the POW hospital camp where I was posted as interpreter after the return from “up-country,” the survivors seldom spoke about their year at the Three-Pagoda Pass. A sense of propriety held us back from closely investigating the factors that had kept us alive while many fitter and worthier men had gone under.

“It’s all a matter of luck,” we said.

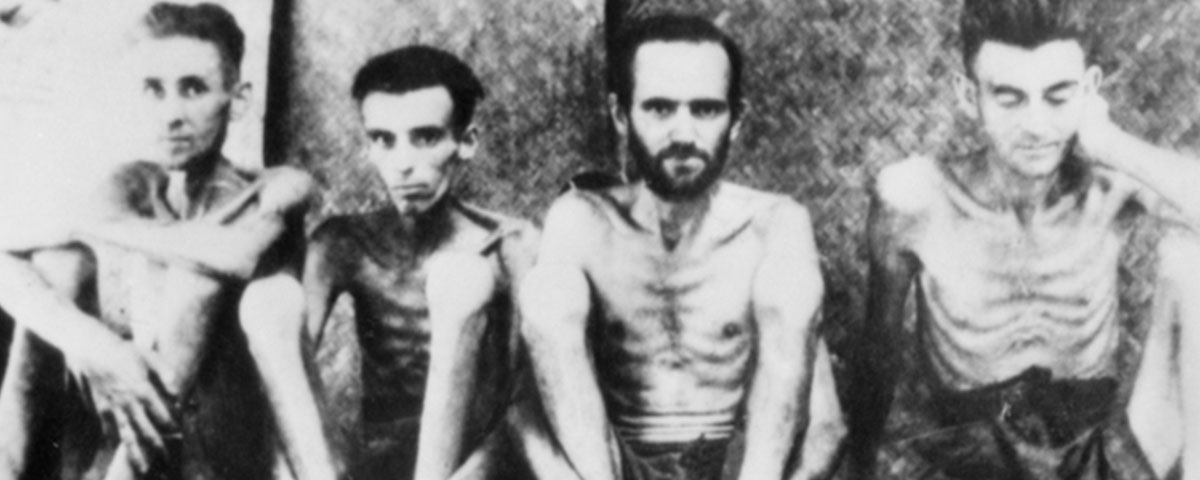

It was indeed luck, or the accident of birth, if you were the right size. Everyone received the same quantity of food—except the sick, who were allotted no food at all by the engineers. (“No work, no rice” was their rule. Consequently, the healthy shared their scanty rations with the sick.) When, with the monsoon rains, neither bullock carts nor even elephants could negotiate the track, which had been transformed into a flowing stream of mud, we sent small parties of men to pick up what they could carry from camps on the other side of the pass. We all teetered at the edge of survival, but the tall men, needing more calories than their smaller comrades, were more vulnerable. The Military Police, all of them six-footers, were the first to go under. On the other hand, a smaller man might find the work imposed by the Japanese a lot harder than a big one. The most obvious, the most visible, causes of death—malaria, cholera, dysentery, and tropical ulcers—were enormously aggravated by starvation.

Curiously, a man’s height might also influence his treatment at the hands of guards and engineers. A tall man, regardless of the respect accorded to stature in all societies, might present a challenge to an undersized private who passed on to the prisoner the slaps and blows that were part of the IJA routine, administered from higher to lower rank. As he might find it awkward to deliver a sharp upward swing to his victim’s face, he’d concentrate on chest, belly, and limbs—more damaging than conventional slaps. Conversely, harsh punishment might harm the small and weak more than the large and strong. Luck, then, was to be below 6′ and above 5’8. I happen to be 5’8.

Luck, too, if you had received proper food in your youth. There was a difference in the survival rate if your family had been poor or well off, if you had been brought up on a diet of sweet tea, biscuits, and occasional fish and-chips, or on vegetables, fruit, and proteins. Because of their general state of health at the start of their three-and-a-half-year imprisonment, officers fared better than other ranks, as everyone not holding the king’s commission was then called, and men from country-recruited regiments better than those born and bred in large cities and industrial areas.

Age mattered. On the Death Railway, the very young, who lacked endurance, and the older men, who lacked quick powers of recuperation, lost out. Colonel Julian Taylor, a celebrated London surgeon and yachtsman (to whom I was teaching French in return for a course in celestial navigation), thought that 27 was the optimum for an infantryman, the age when endurance and recuperative powers are ideally balanced.

Both the strength and the weakness of youth were illustrated by an incident that took place a few days after the February 15, 1942, surrender of Singapore. In the middle of the night, Taylor was called out to operate on a man whose head had been partly severed by a sword blow. He was a sailor in his teens who had been captured a few hours before the cease-fire. Exceptionally, his life was spared. The officer in command of the unit that had captured him ordered a car and driver to deliver the young sailor to Changi. By evening, however, prisoner and driver were back, having failed to find the POW camp. The officer, estimating that he accomplished his humanitarian duty, decided to behead the prisoner. It must have been a perfunctory blow, for some hours later the boy came to, covered by a thin and loose layer of earth. As he tried to crawl out of his grave, he noticed that the muscles of the neck had been partially severed. Holding his head between his hands, he stumbled into a kampong, a native village, from which he was led by two Chinese to the edge of Changi and the POW camp. He was discovered and rushed to the hospital. His youth and vitality allowed him to survive the shock and the loss of blood. A year later, however, he died of disease and privation in the Burmese jungle.

NOT MUCH COULD BE DONE TO CONTROL or influence the existential aspects of our lives. Where you landed on the Death Railway was entirely a matter of chance. Parts of the line were preferable to others, especially if they were close to a base with food supplies or in open rather than hilly country. Certain work assignments, such as rock-blasting, were hazardous; working immersed in the river day after day was invariably fatal. Some guards and engineers showed compassion, while others were sadists who drove their working parties with barbed-wire whips. If your blanket was stolen while you were away at work, your chances of survival precipitously diminished.

Camps, of course, differed. Sonkurai, where I was sent as interpreter after a forced march of two weeks, acquired the worst reputation of any camp on the railway. Cholera had broken out and the Japanese had ordered the sick to be removed to a hill, without shelter, to die under the monsoon rains. Men worked 16 hours a day, and rations were down to a few ounces of rice daily. The engineers were so ferocious that even our own guards, Koreans under the command of a Japanese regular sergeant, were terrified of them. The prisoners—or what was left of them—were set first to building the road, then laying down a railway track, and lastly erecting a bridge over a river. Discipline, social cohesion, and the esprit de corps that is the fundamental glue of the regimental system in the British army all vanished. Men hunted for food and basics in tiny groups. Only one man in 10 survived Sonkurai.

Yet only three miles away, the Australian camp, Shimo-Sonkurai, also part of F Force and subject to the same conditions, was utterly different. As a rule, the Australians fared better than the British, who in turn were better off than the Dutch. Worst of all, way behind the Dutch, came the Asiatic coolies.

The few Americans, airmen and survivors of the USS Houston, sunk off Indonesia in early 1942, made out well. They all appeared to possess a remarkable ability for commerce, even in the jungle. Perhaps because they owned objects the Japanese found highly desirable, such as Rolex watches and Parker Pens (the national passion for the proper label was even then evident), they started off with a substantial capital. Freewheeling and unhampered by the British class system, they were more nimble and more resourceful than the other prisoners, with perhaps the exception of the Australians.

Most Australians came from the bush. They were hardened by outdoor life and resourceful in the wilds—characteristics that under the circumstances were far more valuable than being streetwise. Above all, solidarity between officers and men was maintained; and among the men, mutual help was the rule. The contrast between the two camps was dismally visible every time I went over to help out the Australians, who didn’t have a Japanese speaker among them.

The Dutch, among whom were found a high proportion of Indonesians familiar with life in the tropical forest, should have fared better than anyone else. They, too, suffered from social disintegration, however, and were unable to maintain an effective internal organization. The British found them “selfish”: Without a collective framework, everyone had to fend for himself.

As for the miserable Asiatic levies from Malaya, Thailand, and Burma, they were beaten to death if too sick to work, their scant rations were stolen from them, and they died by the tens of thousands. When the rail link was completed, the Japanese told them they had no use for them anymore, and let them starve to death in jungle clearings. They lacked what our captors admired most: a strong social cohesion whose natural concomitants are discipline and devotion to duty.

BUT IT WASN’T ALL a matter of luck.

Like everyone else in F Force, I had my own explanation for making it back to the POW camps of Singapore, which to the survivors appeared like holiday resorts. At this great remove, however, I can’t vouch whether these ideas came to me when I was on the railway, in Kranji after my return, or since the end of the war. What is certain is that, at the time, I had no doubt that I owed my life to being an interpreter.

Obviously, the scant rations held me up better than if, day after day, I’d been engaged in excruciatingly hard manual labor. But equally important was the nature of the work itself. Unlike the figure of Colonel Nicholson in The Bridge on the River Kwai, clearing the jungle and building a bridge for the benefit of the IJA gave us neither a feeling of pride nor one of achievement. On the contrary, our efforts clearly served the enemy. As a form of morale builder, we collected termites and released them into the pilings. The gesture was meant to give our lives a semblance of purpose, but the bridges were destroyed by aerial bombing long before the insects could prove their worth.

Deprivation of a meaningful activity induced such a sense of worthlessness that on two separate occasions a prisoner approached me with a request to enroll in the Japanese armed forces. I produced lurid accounts of the trials of serving as “one-star” private in the IJA, and worse, of the horrors inflicted on the heihos, the foreign auxiliaries such as our Korean guards. One measure of their low status was a singular restriction: They were not thought worthy of receiving the standard Japanese rifle, supposedly entrusted by the emperor to each recruit, as attested by the crest of the Imperial Chrysanthemum embedded in the stock. The Koreans had to make do with captured British Lee-Enfields. If I failed to deter my would be recruit, I turned him over to one of the better padres.

Because of its direct bearing on our relations with the Japanese, my work could affect, positively or otherwise, the welfare of the camp as a whole. My duties went beyond mere translation. In many situations the interpreter, with a better understanding of Japanese mentality than his superiors, might advise them to adopt a different approach; and if the confrontation took an ugly turn, he might be able to protect the officer for whom he was translating by blaming his own inadequacy with the language. No two situations were ever alike. In every confrontation there was always the possibility of winning, and this prevented me from the dumb and passive acceptance of orders. Alas, there was an unpleasant price to pay for this. Being frequently around the Japanese, I was often the recipient of slaps and blows.

A signal privilege of my work was the exposure it gave me to a culture utterly different from the one I had been brought up in. Much had been imparted by the two British interpreters who had been my teachers, but nothing matched those insights I received on the job. One remains upper most.

It occurred when I was the interpreter at Tambaya, a camp at the edge of the jungle, on the Burmese side of the Three-Pagoda Pass. There the engineers had dumped about 2,000 F Force prisoners who were expected to die within a few weeks—throwaways, irremediably sick men from whom no more work could be expected. It was also a way, they imagined, to stop disease from spreading.

The commandant was a Lieutenant Eraiwa, a stern combatant officer who, by and large, treated us fairly. His quarters were at the extremity of a long and narrow hut that also housed his men. When I called on him, Eraiwa was seated on his bamboo sleeping platform. I entered, bowed, and, as I did so, noticed a surprising sight through the opening of the partition that separated the lieutenant’s section from that of his men. A tree branch, pale gray, four or five feet in length, was hanging like a painting on one of the bamboo walls. It instantly evoked an ideogram written by a master. It incarnated both perfect equilibrium and dynamic strength. Neither leaves nor shoots impaired its linearity. Finally, its placement on the wall had been perfectly chosen.

A devil sprang in me, a fit of jealousy. Another tribe, an enemy tribe at that, had produced what I perceived as an extraordinary work of art, objet trouvé though it was. The emotion transformed itself into an acceptable form—disdain for such tomfoolery. Yet when I asked Eraiwa the meaning of “that thing on the wall,” I could hear the bitterness in my voice.

“This morning,” he answered slowly, “two of my men went for a walk in the forest. They found this branch, brought it back, and hung it in their part of the hut in order to refresh the spirit of their comrades.”

I bowed once more when I left. Because I had to, and also in acknowledgment of Eraiwa’s lesson.

UNDER THE EXTREME CONDITIONS OF SONKURAI, I came to understand advice I’d been given in Singapore during the early days of our captivity. Its role in my survival may have been even greater than my position as interpreter.

The words were those of a captain in his late forties. One evening, after a game of bridge, he reminisced about his experiences in the First World War and warned us of the days to come.

“Who knows where we’ll be sent to,” he said, “or what’s going to happen to us. We’ll be in the bag for a long time. I was taken prisoner by the Germans in ’17, and I’m sure of one thing: It was a picnic compared to what’s awaiting us. But remember: Whatever happens, however dreadful the times you’ll be going through, you’ve got to be able to say, ‘This is something I never would have had the chance to see otherwise.'”

We looked at each other, the three young men who’d been playing cards with the captain. No doubt each of us was thinking, What’s he talking about? It’s bad enough here in Changi.

It was necessary, said the captain, to draw nourishment from the circumstances. Even though they seemed unbearable, they were exceptional. At the end of each day it should be possible to look back and say, “Today I have seen this, I have learned that.”

“This is what will keep you going,” he continued. “Just now your heads are filled with hopes of home. But that won’t last forever. Memories of home will fade, become distant and unreal. Hope will thin out and won’t sustain you anymore.”

He was right. Deficiency didn’t apply only to calories and vitamins. Pain and overwork drained a prisoner’s psychic reserves. His will to live was whittled away. Despair set in. The threads that tied him to life, both his past life and the present one, slackened. As his attention failed he became vulnerable to the stresses of a harsh and dangerous existence. “Give-up-itis” set in, in most cases irreversible.

I’m thinking of L., a charming and cultivated friend. He was physically strong (he had rowed for his college at Oxford); his mind was incisive and his speech elegant. It was also obvious that he was ill-equipped to deal with les détails matériels de la vie, but there were always friends to take care of him and ensure his well-being. He was a life enhancer; we didn’t want to lose him.

A disaster befell him during the early stages of the long and dreadful trek to the Three-Pagoda Pass, when the columns were traveling through semipopulated regions: The whole of his kit, loaded at considerable expense onto a bullock cart, was stolen. Even though there was always someone ready to share with him blanket and messtin, inevitably it made life much harder. L. arrived in Sonkurai suffering like everyone else from malaria and dysentery, but also profoundly discouraged. Much of his self-respect had disappeared; he no longer bothered to shave or wash. We managed to keep him off road and rail duties, finding him an easy job inside the camp, boiling water all day. But he failed at that and was sent off to work with a particularly murderous gang of engineers. His health and morale declined further. Once more, with the proper approach to the British senior NCO responsible for selecting the work parties (an approach backed by a twist of native tobacco and a spoonful of shindegar, or palm sugar), we kept him in camp for a few days. By that time all he owned were a grubby singlet, a shirt in shreds, and a few rags around his middle. His health declined and he was moved to the so-called hospital hut. Friends brought him rarities that had been hoarded since Singapore or bought from the coolies—an egg, tinned milk, a scrap of dried fish. He gave everything away, and died quietly two and a half months after his arrival in Sonkurai.

Death was part of the day’s events. For many teetering at the edge of the decision whether to fight or to give up, death was the escape from hopelessness. Men died without fuss or struggle to hang on. They didn’t call for someone to hold their hand, to be present at the extinction of life. It was a private and natural affair. The rites of passage were faced alone. Often, there was a smile on the face of the moribund: He was about to find deliverance.

EVERYONE WAS AWARE OF DEATH’S closeness, but few consciously acted on the obvious questions: Will I really do anything to survive? What means shall I use? What compromises will I accept?

Those who said yes to the first mostly went under. The mere will to live apparently didn’t suffice. Even when efforts to find more food and avoid the more strenuous work gangs were successful, the time came when you found the rewards wanting and solace nonexistent. You abandoned the struggle.

The other two questions were answered by a friend, Olaf Moore, a rubber planter before the war, who, when he saw the breakup of moral law in Sonkurai, said to me: “I don’t know how to make my own rules. I won’t start on that. All I think I can do is live like a Christian.” I understood him. But I also feared for his life, and I was right, for within a month he died. Unwilling to engage in black-market transactions, to accept favors, to try to be assigned to light duties, or even to scrounge for food, he found himself among the most dispossessed. He became one of the prisoners who worked hardest and longest and received least.

Between the two groups, those who would stop at nothing and those who could never compromise, came the men who feathered their own nests as best they could, without, if possible, raiding their neighbors’. They were the pragmatists, and some of them survived.

In Sonkurai, not many. Of the 1,600 men who had arrived in May, only 400 returned to Singapore when the camp was evacuated eight months later. And of those 400, only 182 were still alive by the war’s end.

A proper understanding of the Japanese attitude toward prisoners inevitably had a bearing on our welfare. It was a mistake to lump all Japanese into one mold; yet their common view was that, because we had perrnitted ourselves to be captured, we had forfeited all honor. Still, we existed within the military structure of the IJA, and the image that we projected was important, because the Japanese were sensitive to signs. In a rigidly structured hierarchical society, it was necessary to signal one’s proper place in the structure. Two signs were expected of us: one to denote the prisoner’s acceptance of his place, the other to confirm his understanding of his duties—namely, obeisance, observance of the rules, and devotion to work. If, over and above these signs, the Japanese detected indications that evoked “the way of the warrior,” the virtues found in Bushido, they were susceptible to a change in attitude. The possibility then existed of overcoming to a small degree the shame and degradation of our status as prisoners.

As we embodied the virtues of Bushido in varying ways, so were we treated. The senior medical officer at Tambaya, Major Bruce Hunt, a fearless Australian whose unorthodox and vigorous measures were admired by the prisoners, was detested by the Japanese. They didn’t deny his courage, but they found him lacking in that primordial samurai characteristic—loyalty. To them, loyalty meant respect for the IJA, and Hunt never hid his contempt for our captors. Ironically, the very source of his popularity with us rendered Hunt ineffectual in his dealings with the Japanese.

On the other hand, Lieutenant Colonel F. J. Dillon, an Indian army regular, understood the Japanese game and played it well. He dressed as neatly as possible, maintained at all times the Sandhurst posture (feet apart, spine slightly arched backward), and projected the picture of the perfect soldier. Among the prisoners his moral courage was famous up and down the line. Once, however, in his military zeal he overstepped the limits of the possible. In the jungle, after work, he instituted parade-ground drill. The sight of emaciated men, barefoot and in rags, square-bashing in the mud under the dripping jungle canopy, to the bark of the NCOs’ “Mark time! Eyes right!” was bewildering even to the Japanese. The exercise lasted only a couple of days.

Dillon’s axiomatic pronouncement was that without their officers, men perished. The truth was that survival depended more on the military framework itself than on the personal ability of most of the prisoner officers, who often were found wanting when it came to saving lives in the extreme conditions that were the norm on the Death Railway.

Yet such was the gap between officers and other ranks in the British army of that period that a corporal once remarked to me, “You know, there’s really more in common between the Jap lieutenant and our officers than there is between them and us.” This was at Tambaya, where relations between Lieutenant Eraiwa and our officers were based on mutual respect. The corporal was right, and I sensed his secret humiliation. He had correctly perceived the common imprint that codes and manners leave on the different strata of society, leaping over national and cultural differences, and bridging classes. This was the theme of the Jean Renoir film about French POWs during World War I, La Grande Illusion, and nothing much in that sphere seemed to have changed. Nor in fact since James Boswell hung on Samuel Johnson’s every word: “Gentlemen of education [Dr. Johnson observed] were pretty much the same in all countries.”

For myself and for many others, it was easier to seek solace in nature than in human society. We never failed to crane our necks when the greater toucans flew above the canopy. If we couldn’t see them, we could hear the slow and powerful stroke of their wings.

I’d always had an affinity for elephants, and now I observed the intelligence and the delicacy these large animals would apply to moving a log that had become jammed in a gully, or to disentangling a towing chain wrapped around one of their legs. I learned much elephant lore from a Burma teak planter, an elephant wallah. These observations became part of the day’s “nourishment,” a glimpse also into a world both normal and harmonious.

Orchids and butterflies exploding into evanescent bursts of color brought poignancy, even tenderness, into our lives. In Tambaya I once observed a butterfly hovering above the bare foot of a corpse that had been laid out at the entrance to a hut. The insect’s wings were shimmering with gold, yellow, and Prussian blue. Exceptionally large, it was looking for a suitable landing place. It chose the corpse’s big toe. The two polarities, the brilliant, quivering insect and the pale, inert flesh, dissolved into one perception, in an instant as ephemeral as the flutter of gold on the butterfly’s wings. I glimpsed the wholeness of everything around me, but at the same time I understood that I was seeing a reflection of my own mind.

Searching for quietude, I’d walk off into the jungle and sit in a small clearing. On rare occasions mind and body, kneaded by an involuntary asceticism, produced a tiny anthropomorphic experience. The boundaries of self appeared to fuse with oneself, and I entered into a brief but primal communion with my surroundings. In these moments of aloneness, I felt neither separateness nor threat nor hostility.

THE CAPTAIN HAD BEEN RIGHT. When starved and worked to death in jungle camps, thoughts of home and freedom widened the gap between the reality and the hope. Only the present counted, not the past or future. He had been right when he spoke of “nourishment,” when, at day’s end, it was still possible to say, “This I have seen, that I have heard.”

Everything around us was utterly new and unexpected. We had been prepared for none of it. Not for our extraordinary habitat, the rain forest; nor for our association with another people, another culture, the Japanese; and certainly not for the breakdown of our own group structure.

With its societal skin flayed, human nature became visible as never before. Greed, cowardice, and vanity; perseverance, altruism, and generosity—in brief, the wide panoply of vice and virtue was there to be observed in the open, without pretense, with no place to hide.

The captain, I later found out, died in Nikki, the base camp of F Force. So, after all, if your luck had run out neither “philosophy” nor help from your friends, nor even your own determination never to give up, was of much help. Your “number was up,” as we used to say. Or shikata ga nai, to put it the Japanese way: “There is nothing to be done.” MHQ

JOHN STEWART was David Lean’s (mostly ignored) technical adviser during the filming of The Bridge on the River Kwai. He is a photographer and author of To the River Kwai: Two Journeys—1943, 1979 (Bloomsbury, 1988).

[hr]

This article originally appeared in the Spring 1993 issue (Vol. 5, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Death and Life at the Three-Pagoda Pass

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!