In a special three-part series for the month of April, the International Churchill Society has been hosting live events with prominent historians, generals, and authors to discuss all things Winston Churchill.

This past Friday, April 17, Dr. Andrew Roberts, an eminent Churchill biographer, and retired Gen. David H. Petraeus, former Director of the CIA, met live to discuss leadership in times of crisis.

Roberts, the highly acclaimed author of Churchill, Walking with Destiny spoke with Petraeus—whose distinguished Army career included command of forces in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—about the lessons to be learnt from Churchill politically, as well as the practical applications of history within the military sphere.

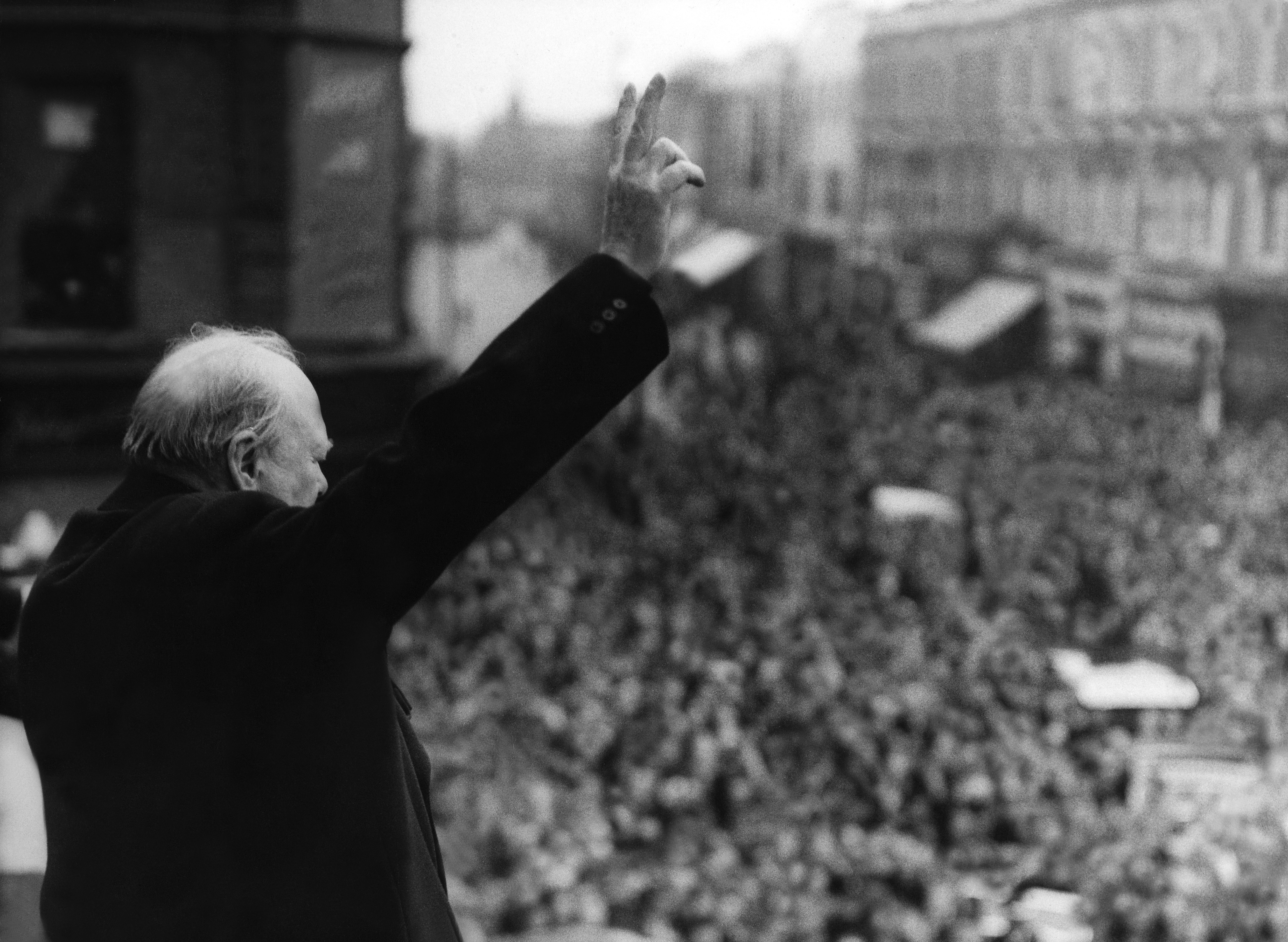

In the face of adversity, says Roberts, Churchill’s instinctive reaction was to presume and encourage resiliency—not only personally, but publicly.

According to Roberts and Petraeus, here are five lessons on leadership according to Churchill:

You can tell people terrible news. Churchill had an almost “tonal sense of what was required” and what the British people could take and what they could hear, said Roberts.

In his May 13, 1940 speech to the nation—only three days into his premiership—Churchill famously offered “nothing but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.” Telling the nation, “We have before us an ordeal of the most grievous kind. We have before us many, many long months of struggle and of suffering.” This set the tone for the British nation at war.

Science is key. Churchill, Roberts posited, quite keenly understood that scientists had a very important role to play in winning the Second World War. From the discovery of penicillin to the atom bomb, science helped win the war for the Allies. The prime minister’s best friend, Frederick Lindemann, was a famed physicist and a key scientific advisor to Churchill who greatly influenced Churchill during the war.

Petraeus outlined his own Churchillian method as it relates to COVID-19; asserting that in times of crisis leaders must: Get the big idea correct up front; explain it in a way people will embrace; oversee the implementation of that big idea; and then constantly retune and refine the idea as the situation shifts.

Write down your worries. Every night Churchill would “self-court martial” about what he hadn’t done that day…and what he could have done. He would write down a list of his worries so he could see, according to Roberts, “the ones that shouldn’t worry you at all, and secondly, you can put the [worries] in order.” These two things, the historian said, could “certainly help any leader today.”

Use history as a guide. Roberts put it succinctly by quoting Churchill—“Study history, study history. In history lies all the secrets of statecraft.”

“History can illuminate but also obfuscate,” said Petraeus. When looking at Vietnam “the lessons weren’t all crystal clear. You have to determine what is applicable from a particular historical incident.”

Paraphrasing Henry Kissinger, Petraeus pointed to the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and how it shaped the statesman’s views on world order. “Those who most want peace” said Petraeus, “often find it quite elusive. Whereas those who are willing to go to war, if necessary, may be able to form a more durable, legitimate political order.”

The lessons of history, Petraeus remarked, are of enormous value.

Better be lucky than good? Churchill had been preparing for premiership all his life. There were moments of extreme calamity—the Gallipoli campaign to name one—where Churchill was extraordinarily unlucky, but the remarkable thing was, according to Roberts, “Churchill learned from every single one of his mistakes.”

After Gallipoli, and nearly a quarter of a century later during World War II, Churchill never once overruled his chiefs of staff. Part of being a good strategist is “cutting down the opportunities for bad luck,” Roberts remarked. Which is precisely what Churchill did.

Churchill was an historian first and was quick to recognize the three major threats to freedom in the 20th century: the threat of Germany before the First World War; the threat of Nazism before the Second World War; and Soviet Communism and Stalin’s imperialism in Eastern Europe. Churchill gained such insight through a profound understanding of history.

For Petraeus, luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity, and in his opinion, no one could have been more prepared for what Churchill was called upon to do. “Churchill was lucky,” Petraeus said. “And extraordinarily good.”