In June 1928 Aviation Cadet Albert Paul Mantz had the world by its tail feathers. The 24-year-old, high on the honors list at the U.S. Army flight school at March Field, Calif., had more than 125 hours in the air, needing just one more hour of solo time to graduate the next day.

He took off in a Consolidated PT-1 Trusty biplane trainer and followed the Southern Pacific rail line east toward Whitewater. Spotting a train laboring up 2,600-foot San Gorgonio Pass, he decided to have some fun with it, and rolled the Trusty over and down to pull out just above the tracks, headed right for the locomotive. As the engineer blared his whistle, Mantz pulled up just enough to miss its stack and buzzed the length of train, for good measure doing a low roll past Whitewater Station, giving a wing-wave to passengers as they hit the dirt.

When he landed back at March Field, he was arrested on the spot. The train had been full of Army Air Corps brass, coming to attend the graduation ceremony. Mantz was dragged before a disciplinary board and dismissed, his Army flight career over. And they hadn’t even found out he’d faked two years of college at Stanford University just to get in.

Mantz found work as a flight instructor and distributor for Consolidated Aircraft, manufacturer of the Fleet two-seat biplane trainer. On July 6, 1930, for the dedication of the San Mateo airport, he flew a Fleet Model 2 through an eye-popping 46 consecutive outside loops. (The previous record was 19.) With that achievement on his resume, he found work as a pilot for the nascent movie industry. His United Air Services in Burbank soon became a private airline for film royalty—the “Honeymoon Express” to Las Vegas for quickie marriages. “They call me Hollywood’s Flying Cupid,” Mantz said, “but it doesn’t make me mad, not as long as it pays dividends.”

But being aerial chauffeur to the stars wasn’t enough for his inner barnstormer. The money was in stunt work. For the 1932 John Ford film Air Mail, he got a job flying a Curtiss-Wright CW-15N through a hangar with less than five feet to spare off each wingtip.

With his reputation flourishing, Mantz’s celebrity client list soon included Howard Hughes, Veronica Lake, Wallace Beery and Amelia Earhart. In 1934 he began instructing “A.E.” in long-distance navigation. He acquired the Lockheed Model 10 Electra for her proposed around-the-world flight (over his personal recommendation, the amphibious Sikorsky S-43 “Baby Clipper”—advice which, if Earhart had taken it, might have saved her life). She parked the Electra in Mantz’s hangar, rented a house nearby and ultimately was implicated in his 1936 divorce, though allegations by his wife that they had carried on an affair didn’t hold up in court. Mantz tried in vain to teach Earhart radio communication and navigation, but she told him, “I will just turn the knobs until I get what I want!” That was undoubtedly a factor in her disappearance over the Pacific in July 1937.

The next year Mantz married Terry Minor, widow of air racer Roy Minor, and began dabbling in air racing himself. He bought his hero Jimmy Doolittle’s Lockheed Orion 9C (one of just 35 made, and today the sole surviving example) and placed third in both the 1938 and 1939 Bendix Trophy Burbank-to-Cleveland races. Meanwhile his subsidiary company, Paul Mantz Air Services, furnished pilots and aircraft to all the major studios (motto: “Anytime–Anywhere”), even hauling a 600-pound Technicolor camera and crew through air maneuvers to follow the action in 1941’s Dive Bomber, with Errol Flynn and Fred MacMurray.

Filmed with the cooperation of the U.S. Navy—and in retrospect notable for its views of the carrier Enterprise just prior to Pearl Harbor—Dive Bomber proved Mantz’s worth to the military. Chief of the Army Air Forces Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold enlisted him as a major in the USAAF’s First Motion Picture Unit—“Hollywood’s Army”—under command of studio boss Lt. Col. Jack L. Warner. The unit would churn out more than 400 propaganda and training films. Mantz flew on bombing raids over the Mediterranean and worked with stars such as Clark Gable, Alan Ladd, Van Heflin, George Montgomery and future president Ronald Reagan, making connections and developing innovations in aerial photography that would serve him well in the future.

In 1946, with postwar America scaling back its expensive military, Mantz paid $55,000—less than the cost of one new P-51 Mustang a few years earlier—to buy 475 surplus aircraft that had originally cost taxpayers $117 million. Mantz boasted that his private air force (including 75 B-17 Flying Fortresses, 228 B-24 Liberators, 10 B-25 Mitchells, 22 B-26 Marauders, six P-39 Airacobras, 90 P-40 Warhawks and 31 P-47 Thunderbolts) was the world’s seventh largest—bigger than China’s. He picked out the best for his company, kept a pair of P-51Cs and a B-25H for himself, and sold the rest. Just the leftover fuel in their tanks, nearly half a million gallons, more than recouped his investment. He got $160,000 for the scrap aluminum and $100,000 for the Plexiglas. On top of that he sold more than 1,000 perfectly good aircraft engines and all the planes’ oxygen regulators, which the U.S. military bought back (rather sheepishly, one would hope) for $75 each.

Mantz’s chief mechanic, Cort Johnson, stripped his Mustangs of ammo boxes, armor, radios and other superfluous gear, and rebuilt them as air racers. (Right out of the box the P-51C, with its faired canopy, was 4 mph faster than the later bubble-top models.) They sealed both wings to make fuel tanks of them, and Mantz cooled his gasoline to near zero with dry ice to squeeze in extra gallons. Prior to takeoff for the 1946 Bendix race, he said, “It was funny—everybody kept asking me where I intended to land for fuel, with no drop tanks. I shrugged and told them the truth, that I was going to use wet wings. Nobody believed me. I got 875 gallons inside those wings!”

After the wartime layoff, and with the market flooded with cheap warbirds, the field for the ’46 Bendix was the biggest before or since: 22 entries, including four Mustangs, 14 P-38 and F-5 Lightnings, two Bell P-63 Kingcobras, a Goodyear FG-1 Corsair and a Douglas A-26. Four USAAF P-80 Shooting Star jets raced in their own division. Mantz, his Mustang painted blood red with white trim and given his favorite number, 46 (for his outside-loop record), won his division’s $10,000 first-place prize with an average speed of 435.5 mph. His other P-51, flown by Thomas Mayson, came in third at 373 mph.

Naming his Mustang Blaze of Noon after his 1947 Anne Baxter/William Holden film project, Mantz set coast-to-coast speed records in each direction and won that year’s Bendix again. In ’48, flying his second Mustang, The Latin American (and proving that victory wasn’t all in the aircraft), Mantz completed a hat trick, speeding along at 447.98 mph to win by a margin of 1 minute, 9 seconds—the only three-time consecutive Bendix champion. In 1950 he sold Blaze of Noon, which went on to even more long-distance records.

Mantz christened his B-25H The Smasher and, besides equipping it with a refrigerator and toilet as a company plane, modified it into an aerial camera ship with a 180-degree bow window in the nose—perfect for the immersive three-camera, widescreen Cinerama process with which the film industry hoped to compete against television. Audiences taking in 1952’s This Is Cinerama and 1956’s Seven Wonders of the World were awed, and many made a little airsick, by the views of the Grand Canyon, Manhattan Island and other world landmarks as seen through the B-25’s nose. (In several sequences, the plane’s shadow can be seen racing over the ground.) In 1958 The Smasher was also employed by the Walt Disney Company to carry the nine cameras needed for its Circle-Vision 360-degree feature America the Beautiful shown at Disney attractions.

The Smasher flew at 175 knots to keep up with Navy jets in 1954’s The Bridges at Toko-Ri, with Mantz operating cameras in the open-air tail-gunner position; it flew alongside mammoth Convair B-36 bombers in 1955’s Strategic Air Command; and it labored along with gear and flaps down and props set to low pitch to avoid outrunning a Spirit of St. Louis replica in the 1957 Jimmy Stewart film of the same name. For that movie Mantz purchased two Ryan B1s and had them converted to match Charles Lindbergh’s Ryan NYP. Each had a ghost cockpit for the actual pilot installed in front of the movie cockpit. Cowl panels, removable depending on the camera angle, covered the windshields. Mantz boasted, “Lindbergh was astounded when he saw our replica of the Spirit of St. Louis.”

For 1950’s Chain Lightning, starring Humphrey Bogart, Mantz built a full-size dummy jet fighter for $15,000. The “Willis JA-3,” looking like a sleeker, sexier Bell X-2 rocket plane, was capable of ground rolls, deploying braking parachutes and exhaust plumes, but wasn’t intended to fly. “I could taxi pretty fast, then turn and stop with the brakes—gently,” Mantz recalled, “but it had no ailerons or rudder so it was a real shock when I came down the runway too fast and found the damn thing starting to take off. It was so clean it just wanted to fly!” (One of the reasons the “jet” was so clean was that it had no air intakes.) The movie also featured Mantz’s surplus B-17F in flashback sequences, as Naughty Nellie.

Though Mantz built his career on flying, a good bit of it required crashing. He’s the one who bellies-in the B-17F in 1949’s Twelve O’Clock High. Plenty of pilots had solo-landed shot-up Flying Fortresses during the war, but nobody was sure you could take off that way; the throttle levers required two pilots. Offered the then unheard-of payment of $4,500 (about $48,000 today) to perform the stunt, Mantz welded a steel bar across the throttle cluster and got the Fortress airborne but, approaching downwind for the cameras, lost rudder authority and landed off-course, wiping out some film crew tents. Luckily nobody was inside; they were all out to see the stunt. The footage was so good it can be seen again, from a slightly different camera angle, in 1962’s The War Lover, with Steve McQueen.

For John Ford’s 1950 comedy When Willie Comes Marching Home, Mantz, an uncredited stunt pilot, flew a Stearman 75 through yet another hangar, dragging a wingtip on exit, before tearing off its wings between two trees. Mantz, who always said, “I’m not a stunt pilot. I’m a precision pilot,” purposely weakened the Stearman’s wings to shed them as planned. “Your chances for survival and rescue after a crash landing depend largely on how well you succeed in making the airplane, and not yourself, absorb the shock,” he noted. “I’ve lived to walk away from numerous precision crashes because I’ve made it a point to learn what actually kills an airman when a plane crashes.”

Sidelining as a flying ambulance driver and rainmaker, Mantz pioneered aerial fire suppression as part of the U.S. Forest Service’s Operation Firestop. In 1954 he had an ex-Navy TBM-1C Avenger torpedo bomber fitted with an internal 600-gallon water tank lined with a U.S. Weather Bureau balloon, and that September personally flew its first drop against a live fire. The water balloon, distending from the torpedo bay before bursting, earned the TBM the moniker “Pregnant Guppy,” but led to improved systems and a fleet of USFS Avengers and PBY Catalina firebombers.

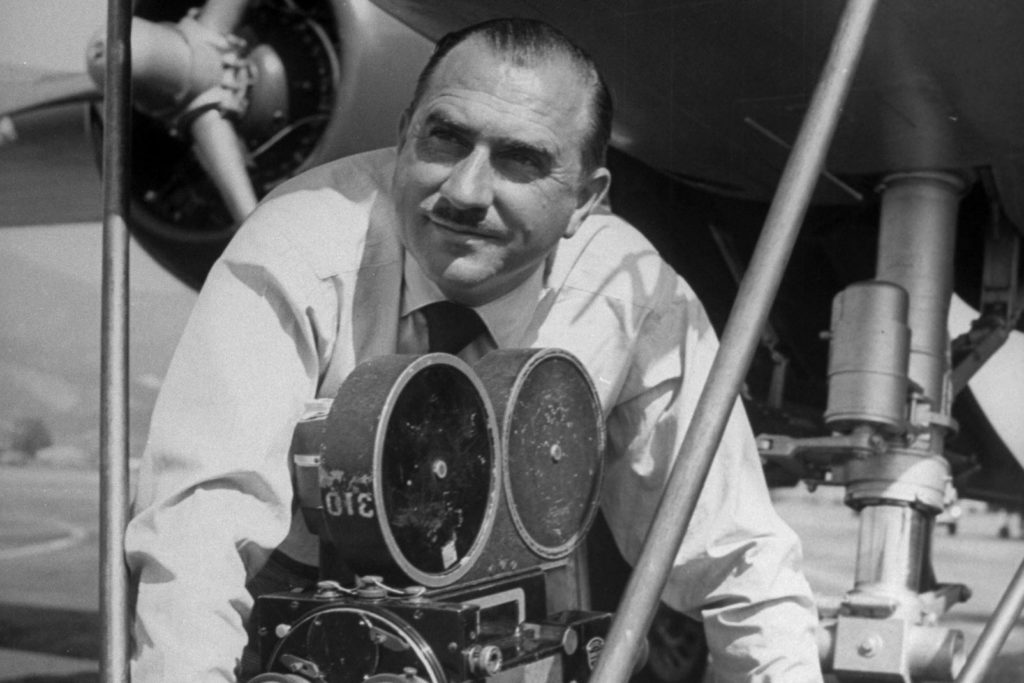

By the early 1960s, Mantz had worked on more than 250 movies and earned in excess of $10 million. He and his family lived on Balboa Island in California or aboard his 80-foot motor yacht. In 1961, at age 57, he partnered with friendly rival Frank G. Tallman to form Tallmantz Aviation, Inc. They housed their combined air fleets at Orange County Airport as “Movieland of the Air”—in its day, the world’s largest air museum. Tallman, 16 years younger, took over most of the company operations. Mantz eased into retirement, telling reporters, “I’ll let Frank do the stunts from now on.”

But in 1965, during filming of The Flight of the Phoenix, Tallman broke his leg off-set. The filmmakers turned to Mantz. “I’m trying to wean myself away from this stuff,” he told the press. “I’m 61 and my ears ring constantly from power dives. But there’s just one trouble. I keep putting my prices so high they won’t hire me—and they keep doing it anyway.”

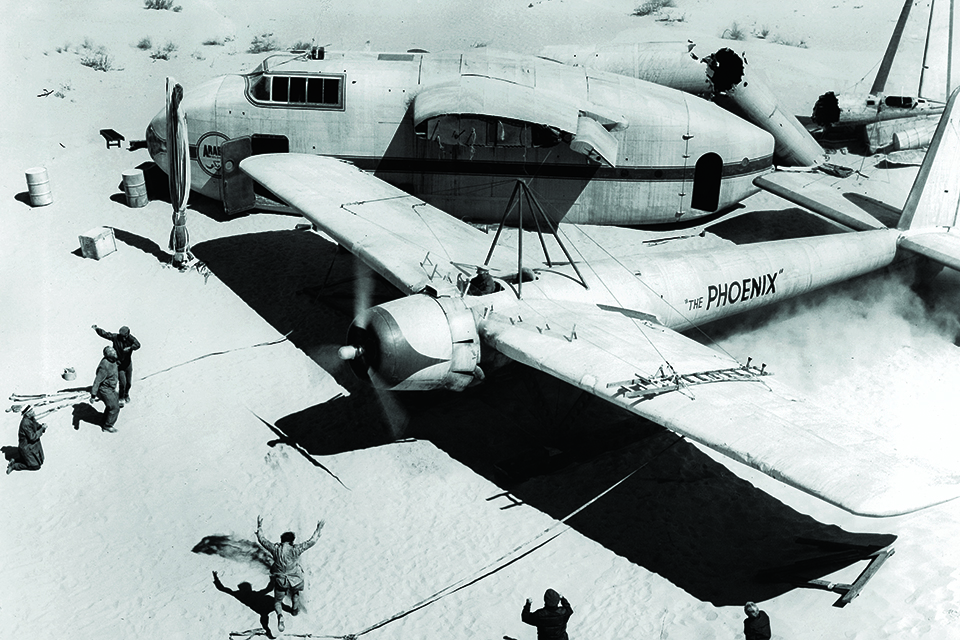

Phoenix, starring Jimmy Stewart, was about the survivors of a Fairchild C-82 Packet that crash-lands in the Sahara, who take advantage of its twin-boom layout to cobble together a new plane from salvaged parts. Mantz had not been directly involved in the construction of the resulting Tallmantz Phoenix P-1, which unlike his dummy jet fighter was required to actually fly. Longtime aircraft designer Otto Timm used the powertrain of a North American T-6 Texan and wings from a Beechcraft C-45 Expeditor; Tallmantz built the fuselage and tail of plywood over a steel-tube and wood frame. The FAA issued the P-1 a Certificate of Airworthiness, and three weeks later, on July 8, Mantz took over for the climactic flying sequence. “It flies like a dream,” he told the press. “The nose gets too heavy at slow speeds, but we can correct that. It can do just about anything.” Privately, though, he thought the plane’s design, without flaps or adequate trim, unsound.

The P-1 couldn’t actually take off from rough ground. So Mantz, with veteran Hollywood stuntman Bobby Rose aboard behind him, would fly it to the set at Buttercup Valley, Ariz., for a touch-and-go that could be edited into a “takeoff.” As usual, Mantz got the shot on the first take, but to be safe, second unit director Oscar Rudolph wanted more. Several cameras captured the resulting crash. Mantz grazes a sand dune at 90 mph. The jolt breaks the P-1’s back, right behind the wings. The nose section, including the open cockpit, somersaults twice before coming to a stop upside-down. Rose survived with major injuries. Mantz was killed instantly.

An autopsy finding his blood-alcohol level to be 0.13 has been disputed by witnesses. “I know he had had nothing to drink,” Mantz’ secretary stated. “I knew him for many years, and he never seemed sharper than he did that morning.” It’s conceivable desert heat might have hastened decomposition, raising microbial ethanol levels. As a friend shrugged, “Drunk or sober, he was one hell of a pilot.”

More than 400 people attended Mantz’s funeral at Hollywood’s Forest Lawn Memorial Park. His pallbearers included Jimmy Stewart, Jimmy Doolittle, John Ford and Chuck Yeager. He left a photo of Amelia Earhart on his desk. In 2006 the International Council of Air Shows inducted Paul Mantz into its Hall of Fame, naming him the “King of Hollywood Pilots.” He died the way he lived: flying for the cameras.

For additional reading, frequent contributor Don Hollway recommends Hollywood Pilot, by Don Dwiggins. For videos of Paul Mantz in action, visit donhollway.com/paulmantz.

This feature originally appeared in the May 2020 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!