ON FRIDAY, JUNE 9, 1893, hundreds of Records and Pension Division clerks, some of them Civil War veterans, filed into their jury-rigged offices in the old Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. Many considered the three-story building dangerously unsafe, a firetrap in “tumble-down” condition. Others believed the one-time Baptist church on 10th Street was cursed: In 1862, it was destroyed in a fire; three years later, President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in an unguarded balcony box there, his horrified wife by his side.

If the clerks read the front page of the morning newspaper, they found plenty of fodder for discussion among themselves. In New Bedford, Mass., the sensational murder trial of Lizzie Borden, accused of hacking her parents to death with an ax, was in full swing. Numerous women attended the trial, leading a reporter to grumble, “housework must be neglected.” And, in the same state, the 59-year-old brother of the century’s most notorious villain was buried in Cambridge. Renowned tragedian Edwin Booth, an obituary noted, was “extremely sensitive” regarding the “insane act” committed at Ford’s Theatre by his younger sibling, Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth.

Paper-pushing government clerks weren’t the only busy workers in Ford’s Theatre. Under the direction of Colonel Fred C. Ainsworth, head of the Records and Pensions Division of the War Department, construction workers were installing an electric-light plant, work that necessitated digging into brick supports in the basement. Several days earlier, clerks had complained about the construction, noting it “imperiled the lives of every man who worked in the building.”

Despite the dangerous work conditions, men went about their tasks in the damp, dark, rickety theater-turned-office space. In the building’s open-floor plan, desks were crammed together in rows. In total, nearly 500 clerks—all male, politically appointed and representing dozens of states—worked throughout the structure. Some Civil War veterans—a few leaning on crutches, others with empty sleeves—were easy to spot amidst the other employees. Among the clerks’ tasks was copying muster rolls and other records of Civil War soldiers, drudgery in the age before copy machines.

Not all of the facility’s occupants were human: A large, white cat loitered in the old theater’s nooks and crannies.

At roughly 9:30 a.m., a “rumble like an earthquake” was felt in the belly of the building, soon becoming a “great roar.” Then came a crash “like the end of the world.” Some thought it was an explosion. On the grand stage of the nation’s capital, 28 years after the assassination of a U.S. president there, another awful tragedy was about to play out at Ford’s Theatre.

Act I: ‘A pit of chaos’

Robert Walker looked up in horror as massive, wooden beams and bricks mixed with mortar crashed through the first-floor ceiling. As if scooped out by a massive hand, a chasm was created from the first to third floors by a collapse inside the red-brick building. “I turned and as I was going over the desk behind me,” the clerk recalled, “I was buried….I had no idea how long I was there. I had given up all hope of getting out. The weight was crushing the life out of me and mortar dirt smothering me.”

Joseph Fought, also sitting at a first-floor desk, was lucky. The ceiling immediately above his head was buttressed by a row of posts and didn’t collapse. Covered with dust, he and several of his co-workers crawled to the front of the three-story building, broke glass in the windows, squeezed through the narrow space and escaped.

Almost comically, another first-floor worker crawled under a row of desks to safety. One clerk escaped death by climbing the shelving on the bottom floor, unsure where he was going. Three men on the first floor saved themselves by jumping into a large vault.

Because an area was roped off for the excavation work on the electric-light plant, fewer employees were at work on the bottom floor than elsewhere in the building. As a result, fewer first-floor workers suffered injuries. On the second and third floors, however, witnesses described frightful scenes.

Upper-floor survivors recalled anguished screams of co-workers, who plummeted into a “pit of chaos.” A third-floor witness said Civil War veterans who worked in the building were the “wildest and craziest.” They “seemed delirious,” he recalled, “and had to be held to keep them from jumping out.” One clerk thought the building had been dynamited. Dust lingered in the air, making it difficult to breath.

In “one of the thrilling scenes of the whole affair,” about a dozen frightened clerks huddled at the edge of the gaping hole at the rear of the third floor. In its agony, the building shook. Expecting the rest of it to collapse, the men were “almost frantic.” Desperate, Ethelbert Baier groped around in the dusty haze until he found a fire hose. Unspooling it, the group slid down the hose to safety. Baier was the first to touch ground. “There was no premonitory trembling or any kind of warning,” he recalled about the collapse. “Just a roar and a crash, and the desk and tables seemed to rise up in the centre of the floor, and then disappear in the blinding dust.”

From the street, Basil Lockwood, a black man 19 or 20 years old, spotted workers waving frantically from third-floor windows at the rear of

the building. He climbed up a nearby telephone pole and somehow leashed a short ladder from the pole to a window sill about eight feet away, creating an avenue of escape for perhaps as many as 30 workers. A month later, the young man was given a “handsome” gold watch in appreciation. “Presented to Basil Lockwood by the clerks of the Record and Pension Division,” the inscription on it read. “In recognition of his heroic conduct in the Ford’s Theater disaster, June 9, 1893.” Even better, the “noble Negro” was weeks later made a messenger in the Records and Pension Division. (In 1895, Lockwood was laid off from the job, a victim of the government’s “reduction in force.”)

Another clerk expected the disaster, even plotting an escape route two years earlier. William Mellach of New Jersey may have been the first to leave. “He always knew,” a newspaper wrote, “the building would fall some day.” Apparently a construction worker excavating in the basement did, too. Shortly before the disaster, he noticed an archway in the building bending, a bad sign. “I tell you I was scared and got out just as quick as I could,” he told a reporter after the collapse. “There were 20 men at work with me….I don’t know what became of them.”

Act II: ‘Wept like children’

Rescue workers quickly arrived on the scene. They were struck by the silence. No cries for help were heard. Perhaps those were muffled by the debris. Sweat pouring from their faces, the first responders worked “like demons,” moving beams, rafters, and rubble as they searched for victims. “It was,” a newspaper reported, “a horrid task.”

News of the tragedy spread with “lightning-like rapidity” throughout the nation’s capital. Every hospital in the city was alerted. Soon, hundreds of people enveloped the building. Men “wept like children” and “women were helped away in the fainting condition.” Witnesses stood on the roofs of nearby buildings to catch a glimpse. Clergy from several denominations flocked to the theater. “This is one of the disasters that cannot be charged to God,” one of them said. “It was preventable; it was foreseen and forewarned, and was allowed.”

Under orders from the secretary of the Navy, naval doctors were sent to the scene. Ambulances arrived to carry away dead and injured. Neighborhood houses, drugstores, and other businesses became makeshift hospitals. Coats, pieces of cloth, or a newspaper were placed over the faces of victims with gruesome injuries. In the shadow of a fruit tree near the building, the bodies of seven victims lay. A white-covered grocer’s wagon carried away a dead man, his head nearly twisted from his body. Friends and family sobbed over mangled bodies.

“That anyone should have escaped with his life seems the work of a miracle,” a reporter wrote. “As [victims] were brought forth they presented a spectacle that no one seeing it will ever forget. In many cases the semblance of humanity was gone. It seemed as though the helpers were carrying out mere bags of matter, smeared all over with blood, filthy with dirt, dirt ground into them, blood on their faces.”

A man was brought from the wreckage on a litter, apparently deceased. Revived by fresh air, he looked around, got up from the litter and walked away. Believed near death, a victim was carried from the building and placed in an ambulance. His face was covered with blood. Stunningly, he popped up on his own. Then he swallowed a glass of whiskey. The crowd cheered. Many victims were blanketed with plaster and dust. Five men injured by falling debris looked like “circus clowns,” according to a rescuer who helped pull them from the wreckage.

At the small city morgue, the scene was a horror show of pools of blood, crushed skulls, broken arms and legs, and discolored faces. Family members searching for loved ones timidly asked for admission. Thousands of curiosity-seekers visited the facility for a peek at the ghastly remains. The overwhelmed morgue had only one dissecting table and a lone ice chest. When it couldn’t accommodate more bodies, a nearby stable was used.

At Ford’s Theatre, desks tipped precariously near the jagged chasm. Records and other papers were scattered everywhere, many spotted with blood. The large, white cat “haunted the ruins like a spectre, apparently looking for its master.” A good Samaritan carried away the facility’s longtime resident. The military was mobilized to provide security and to guard invaluable Civil War records stored in the building. A rope was stretched across the sidewalk to keep back the large crowd, which lingered into the night.

As the rescue and immense cleanup efforts continued into the afternoon, a fireman hosed down the interior of the building to tamp down clouds of dust. A clerk objected, complaining important government papers would be ruined by the water. “We don’t care for the papers of a government that lets its clerks work in such a trap,” snapped another man nearby. “It’s men we are trying to save—not papers.”

Neither Ainsworth nor George W. Dant, the contractor for the Ford’s Theatre work, was present when the catastrophe occurred. “I could not imagine how it happened,” Colonel Ainsworth said after he arrived on the scene. Onlookers soon “muttered threats of lynching.” Later in the day, Dant was at home under a physician’s care, “suffering from nervousness.”

At the White House, a short carriage ride from Ford’s Theatre, President Grover Cleveland was informed about the disaster. Relief groups swiftly raised $5,000. The president contributed a check for $100.

Act III: ‘The horrors grow’

The shocking news traveled rapidly throughout the country, and newspapers published front-page stories with screaming headlines. “Plunged into chasm of death,” one of them blared. “Awful Catastrophe” was another, while an all-caps headline in a New York newspaper noted simply, “Tale of Woe.” In the Washington Evening Star, which printed four extra editions on June 9, a headline signaled the story was far from over: “The Horrors Grow as the Day Advances.”

Newspapers also published lengthy casualty lists reminiscent of those from the Civil War. Final toll: 23 dead and more than 100 injured. The death list contained a number of Civil War veterans, including 55-year-old Samuel P. Banes, who, according to his local newspaper, “met a death as sudden as though struck by a cannon ball on the battle-field.” In an obituary, the Bucks County (Pa.) Gazette lamented the demise of the 3rd Pennsylvania Reserves veteran, who had fought at Gaines’ Mill, Chantilly, Second Bull Run, South Mountain, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and elsewhere:

As his mangled remains were laid to rest, the thought that he had passed unscathed through the dangers and privations of war, although bearing to the fullest degree his share and never shirking a single duty, only to be at this late day hurled into the abyss that yawned for him in the ill-fated building in Washington—that city which he had so bravely defended, forced upon the hearts of those who stood around his grave the truth of the Scriptural teaching—“For ye know neither the day nor the hour wherein the Son of Man cometh.”

Also dying in the collapse was 117th New York veteran Benjamin F. Miller, who had suffered a severe leg wound from an unexploded shell at the 1864 Battle of Cold Harbor, Va., and often was spotted limping around the office. A bachelor, the veteran lived with the Smith family on Q Street. “So long and so pleasant was his stay in this family that he became almost like a brother,” a newspaper reported, “and their grief at his untimely end is as keen as that of blood relatives.”

On June 7, 4th Michigan veteran John Bussius had celebrated his daughter’s marriage with his family. Two days later, his body was identified by his heartbroken son. Bussius’ wife, who had dealt with family tragedy before, was so upset she was “about to be confined.” In 1878, the German-born Bussius’ 2-year-old son was killed on a Washington street, kicked by the hoof of a horse spooked by a mischievous youth with a bean-shooter.

In the rear of Ford’s Theatre, George N. Arnold—“one of the best known and most popular colored men in the city”—had climbed onto a third-floor window sill. Urged not to let go, the 55-year-old clerk did so anyway, plunging nearly 40 feet into the alley where Booth had tethered his horse the night of the Lincoln assassination. “He fell on the covering over a lower door,” a newspaper reported, “and slid off onto the cobble-stones, striking on his head, which was smashed to a jelly.” Arnold had served as a hospital steward for the 4th U.S. Colored Troops during the war.

Veterans Joseph Barker Gage, George Q. Allen, John Chapin, and Andrew Napoleon Girault also died in the tragedy. To each family of the dead men, the government eventually paid $5,000.

Act IV: ‘Blame’

Almost from the moment the calamity occurred, people sought explanations and assigned blame. Many pointed fingers at Congress, saying it knew of the many inadequacies of the government building. Eight years earlier, a congressman said the building was in “absolutely dangerous condition.” Yet Uncle Sam allocated no funds to fix the ramshackle place. “The miserly Congressional fingers,” the New York Tribune wrote the day of the disaster, “are red with the blood that a few hours ago coursed through the veins of active manhood.”

Even 64-year-old John T. Ford, the theater’s namesake and its manager when Lincoln was assassinated, weighed in. He wrote a statement published in the Washington Evening Star three days after the collapse: “The terms used by many of the press, calling the theater a ‘death trap,’ an ‘egg shell,’ etc., are not to be justified, except under the plea of extravagant expressions springing from great excitement. When thorough investigation is made the conclusion now becoming evident that the catastrophe came solely from undermining the supports of the floors….”

Ultimately, it was determined one of the piers had given way during excavation in the basement for the electric-light plant, probably due to inadequate bracing. When the pier collapsed, it took a 40-foot section from all three stories down with it. At a coroner’s inquest, irate clerks and family members of the victims blamed Colonel Ainsworth. “You murdered my brother!” a man screamed. “Hang him!” others cried. Ainsworth, who kept a revolver in his pocket during some of the proceedings, remained calm. Jurors found him, contractor Dant, and two others guilty of criminal negligence. But charges against the colonel were eventually dropped by the district attorney. Ainsworth died at the age of 81 in 1934.

Days after the tragedy, an old man stood in front of Ford’s Theatre. He was there the April night John Wilkes Booth fired a 1-ounce pistol ball into the president’s brain. Perhaps his words summed up best the sentiment of the day.

“There’s a curse upon the building ever since…the great Lincoln was stricken down by the cowardly assassin,” he told a reporter, “and if I had my way it should be entirely demolished and the ground be forever left unbuilt upon.”

John Banks writes from and lives in Nashville, Tenn. He is the author of the popular Civil War blog, john-banks.blogspot.com.

_____

Stacks of Stories

The Civil War service records housed at Ford’s Theatre and the pension files administered at Montgomery Meigs’ pension building are now at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., in a massive collection of records dubbed “the stacks.” The compiled service records track when a soldier was present for duty, wounded, or missing during the war. Many of the more than 2.5 million Union Army soldiers, their

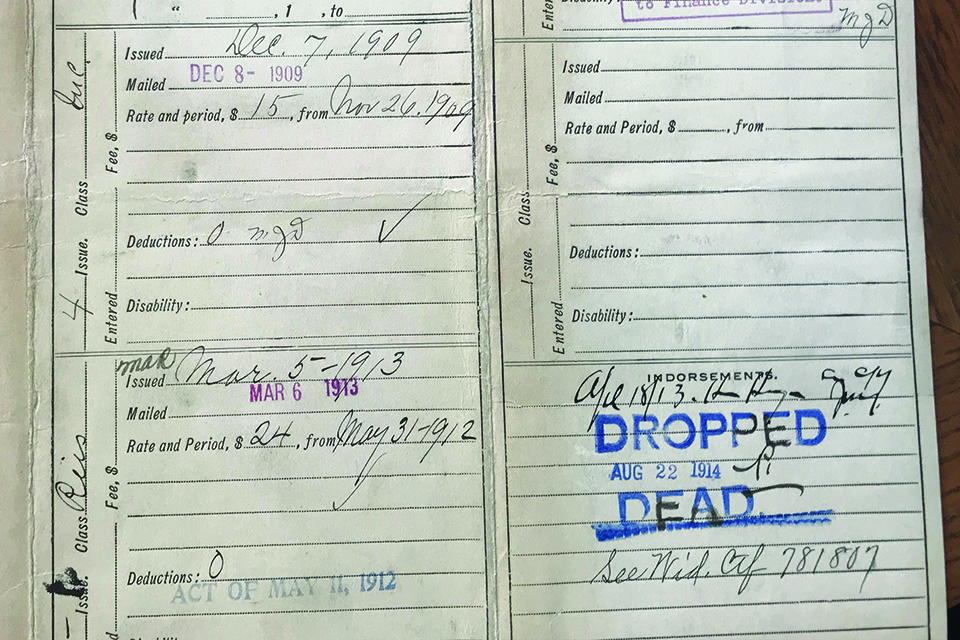

widows, or minor children later filed for pensions. Because the government required applicants to prove pension eligibility, documents often reveal accounts of injury, including battle details and corroborating reports from fellow soldiers or hospital staff. The accounts range from gruesome to bemusing, such as the claim of Corporal Asa Bailey of the 31st Wisconsin Infantry, above, who, according to his application “contracted a rupture in his left groin caused by throwing a cannonball over his head…for exercise and [to] pass time.” To obtain a widow’s pension, a surviving spouse also had to provide proof of marriage. Pension files are accessible to any researcher who visits the Archives. Digitized records are available at Fold3.com. An index of pensions held by the National Archives is available on Ancestry.com.–Melissa A. Winn