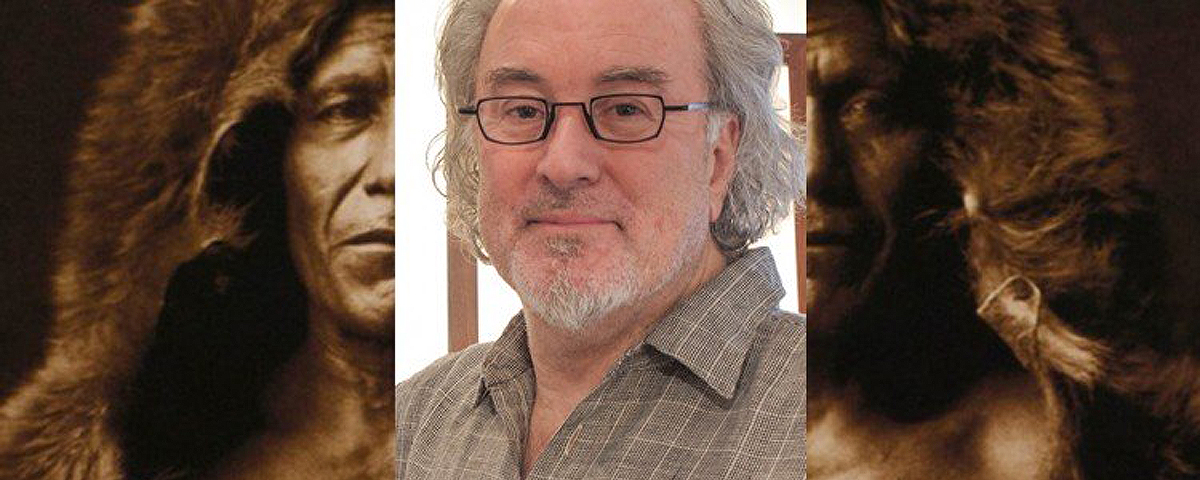

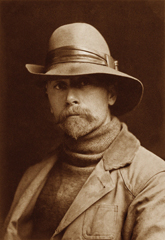

Among the most iconic images of American Indians are those captured in the early 20th century by Edward S. Curtis, a man who gave the field of ethnology a phenomenal resource in his 20-volume collection, The North American Indian. The quest for traditional people to photograph took Curtis among the tribes of the Pacific Northwest, the Plains, the Southwest and other regions. He found support from such patrons as President Theodore Roosevelt and financier J.P. Morgan. One of the world’s foremost Curtis authorities, Christopher Cardozo has developed exhibitions of his photographs that have toured more than 40 countries. Cardozo’s personal collection of Curtis photographs is the basis for his latest book, Edward S. Curtis: One Hundred Masterworks (DelMonico Books/Prestel, 2015). Cardozo recently spoke with Wild West about the legendary photographer and his work.

What first drew you to Curtis’ images?

In 1972–73 I spent six months in an isolated Indian village at the very ridge of the Sierra Madres in southern Mexico. I was living with a group that was a cultural and linguistic island, forced out of all arable land at lower elevations by dominant, larger indigenous groups. There was no electricity, and people were living as they had been hundreds of years earlier. I encountered only three other Caucasians, and some of the indigenous people had never seen a white person before. During that time I made approximately 8,000 negatives, created film footage, made audio recordings of language and music, and collected material culture.

On my return to the United States a friend saw my sepia-toned photographs of the Indians and insisted I look at a just published book of Curtis photographs. This was a watershed experience in my life—to see the work of an extraordinary photographer whose footsteps I had unconsciously been following. Then I heard that Curtis’ archive had been discovered and was being brought to the market. A day later I went to the gallery in Boulder where the prints were being sold and went into debt for the first time in my life to buy two original photographs. Thus, within three days of returning from Mexico, I was led both to Curtis’ work in book form and in the form of original, vintage photographs. I was hooked.

Why do Curtis photos captivate us?

Curtis’ photographs of native people are unique in many ways and on many levels. First and foremost they are the result of a highly collaborative, co-creative endeavor. Even a superficial inspection reveals the native people were critical participants and co-creators. They were as committed as Curtis to creating this record that would become, in many cases, the only record their descendants would have of what they looked like, who they were and what they believed in. In many of Curtis’ finest portraits one sees an intimacy, vulnerability and intensity of involvement on the part of the native participants that simply does not exist in any depth or consistency in the work of any other photographer of the American Indian. There have been thousands and perhaps tens of thousands of photographers who photographed the American Indian, yet rarely do we see other photographs of native people that combine such aesthetic sophistication, vulnerability and beauty of object. Never do we encounter an entire body of work with those qualities, a result of Curtis’ unwavering 30-year commitment to this project—

a commitment that was unique and unprecedented.

How did Curtis meet J.P. Morgan?

Through Roosevelt. President Roosevelt was a great champion of Curtis’ work, and in December 1905 he gave Curtis a letter of introduction to secure a meeting with Morgan the following month. Morgan famously turned Curtis down before even looking at any of his work. Curtis, a strapping 6-foot-1, blue-eyed man of strong will and clear intention refused to take no for an answer and convinced Morgan to look at his portfolio of approximately 20 photographs of Native Americans. According to Morgan’s secretary, the financier then changed his mind for only the second time in 25 years and agreed to provide initial financing for what proved the most ambitious publishing project in North American history.

How important was Morgan’s support, and were there any downsides?

Morgan’s support was critical to the creation of The North American Indian. Without his backing it is unlikely the iconic publishing project would have gotten off the ground. Curtis was constantly on the verge of bankruptcy, as was his company. But for the continuing support from Morgan and his heirs, it is also unlikely the project could have continued past 1914. The downside to Morgan’s support was that some people chose not to support the project, either because they assumed Curtis had all the backing he needed (in point of fact, the Morgan money provided less than one-third of the cost of the publishing project and associated fieldwork), or because they were not enamored with Morgan and his business style.

Did Curtis have other benefactors?

Curtis had many other benefactors, but none remotely to the degree of Morgan and his family. Supporters purchased Curtis photographs, attended his lectures, engaged friends and family members in the effort, lent money, or, as in the case of Roosevelt, gave their full moral and philosophical support to Curtis and his project, and in doing so, they encouraged many others to support Curtis.

What did Curtis sacrifice to relate the cultural stories American Indians?

Curtis essentially sacrificed everything dear to him to create this record that continues to touch so many lives today. He did this, I believe, because he truly loved the native people, their freedom, their connection with nature, and the beauty and integrity of their beliefs and lifeways. He was very clear it was a story that needed to be preserved and told, and he believed he was the last one that would have an opportunity to do so, as much was being lost or destroyed before his very eyes.

How do Curtis’ life and images inspire you personally?

A number of ways. Curtis was a technical innovator, he was a consummate photographic craftsman, and he was gifted as a maker of sophisticated, beautiful images. He had a commitment to his art, his native co-creators, and to the preservation of a unique record of a people that may well be unprecedented in the history of photography. More important, Curtis’ photographs inspire me as a human being.

Edward S. Curtis was a true Renaissance man and American hero. He achieved what many thought impossible and created one of the most enduring and iconic visual records in the history of photographic medium. He was a visionary, an award-winning artist, a consummate craftsman, an intrepid entrepreneur, a technical innovator, a respected ethnographer, a superbly accomplished publisher and a groundbreaking filmmaker. He was a witness, a multiculturalist, an adventurer, a gifted communicator, a mountaineer and outdoorsman, a multimedia artist, a skilled leader and an early environmentalist.

When did you begin collecting his images?

I began collecting Curtis photographs in 1973, just after returning from Mexico. I clearly remember the day, the angle and direction of the sun, where I was standing, etc., when I first saw Curtis’ images in a bookstore in Albuquerque, New Mexico. As a young, naive photographer who had just had what was perhaps the most extraordinary experience of my life, to then discover that someone had done something so similar (yet infinitely broader, deeper and better) many decades before me was earth-shaking. Also, as a young photographer who was still trying to “find his voice,” to encounter a body of work like Curtis’ that was so fully realized, congruent, moving and utterly beautiful was a life-changing experience.

Which of his photos do you prefer?

Virtually all of the photographs in my collection are meaningful to me, though some more so than others. The ones I go back and look at over and over are almost always, first and foremost, beautiful objects. They are what I refer to as “objects imbued with spirit.” They have a presence I rarely see in any other photographs. They embody beauty, heart and spirit and are deeply healing. I tend to gravitate toward, and am most moved by, Curtis’ platinum prints, his gold-toned printing-out paper prints and his cyanotypes. His platinum prints possess extraordinary complexity, depth and richness. His gold-toned printing-out paper prints have a razor sharpness, warm hue and intensity that give them an extraordinary impact. His cyanotypes, because they were made in the field, often within a day of his negative being made, possess an immediacy, directness and connection to Curtis and his co-creators.

How do people from other nations react to his work?

I have created and curated Curtis exhibitions in 40 countries and on every continent but Antarctica, from Papua New Guinea, Paris and Peru to South Africa and many places in between. And I have been amazed at the universality of Curtis’ appeal. I’ve been particularly moved as I observed indigenous people throughout the Americas looking at, and being visibly touched by, the positive, life-enhancing imagery Curtis created.

How would you describe his legacy?

Unparalleled. He helped change the way an entire nation viewed its native people—and did so at a time when many others were still actively advocating for the extinction of all native people on this continent. His work has taught many generations about diversity, inclusion, compassion, environmental concerns, etc. I describe it as a sacred legacy of beauty, heart and spirit. It is fundamentally a healing message that has touched people worldwide for more than a century. In the breadth, depth and power of his work he is sometimes compared to Rembrandt, James Jay Audubon or even William Shakespeare. It is not hard to imagine people will still be moved by his work hundreds of years from now. WW

Christopher Cardozo has written or edited eight books about Curtis, including the monographs Native Nations: First Americans as Seen by Edward S. Curtis (1993) and Sacred Legacy: Edward S. Curtis and The North American Indian (2000). Also visit Cardozo Fine Art online. One Hundred Masterworks is published in association with the Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography. This article was originally published in the December 2015 issue of Wild West. This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.