During four years of carnage on hundreds of Civil War battlefields, a handful of units earned reputations as elite, battle-hardened forces. Soldiers in these units prided themselves on their regiment, brigade, or division’s reputation and laurels, often earned at considerable sacrifice. The Iron Brigade, the Stonewall Brigade, and Cleburne’s Division, for instance, garnered respect during the war and continue to retain popular appeal and reverence. Yet few units stand as distinguished as the Pennsylvania Reserves in the Army of the Potomac.

Through grinding campaigns, high casualty rates, and army reorganizations, the Pennsylvania Reserves served and fought as a division consisting exclusively of Pennsylvania regiments. Far from a reserve or militia unit, as commonly misperceived, the Pennsylvania Reserves saw combat in nearly every significant campaign in the war’s Eastern Theater between December 1861 and May 1864.

In the wake of Fort Sumter, tens of thousands of men throughout the North enthusiastically responded to Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers, and Pennsylvania offered the War Department 25 regiments of approximately 25,000 volunteers. Meanwhile, concerned with the state’s vulnerability to a possible Confederate invasion, Governor Andrew Curtin, a Republican governor elected in 1860, called the state legislature into special session. On May 15, 1861, the legislature authorized the creation of the Reserve Volunteer Corps of the Commonwealth. Funded by state money, the Pennsylvania Reserves would be used in “suppressing insurrections, or to repel invasions” and could be mustered into federal service, “if necessary.”

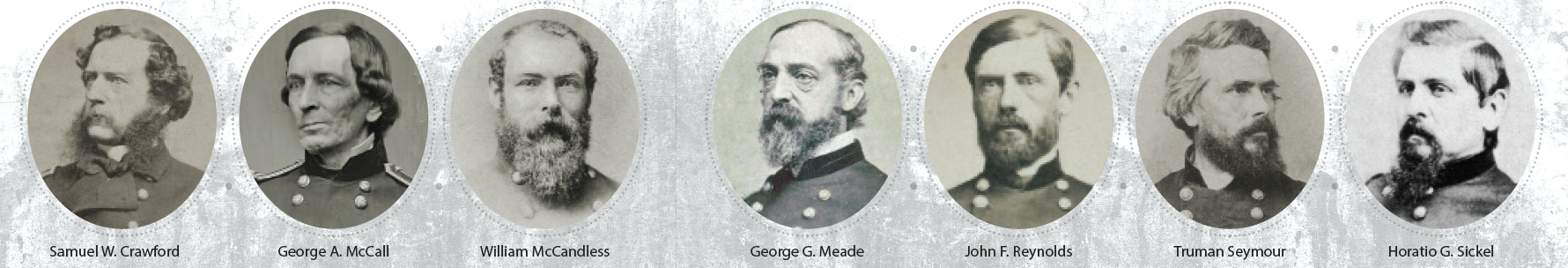

Curtin first offered the command of the Pennsylvania Reserves to George McClellan. Although McClellan, a Philadelphian, had expressed interest in the command, he had just accepted command of the Ohio militia. Curtin then turned to 59-year-old George McCall. A Philadelphian, West Point graduate, and Mexican War veteran, McCall accepted Curtin’s offer at the rank of major general. In early June, volunteers began organizing at four camps throughout the commonwealth and, as new regiments, converged upon Tennallytown, in northwestern Washington, D.C.

Organized into one division of three brigades, the Pennsylvania Reserves consisted of 13 infantry regiments, one artillery regiment, and one cavalry regiment. Brigadier General John Reynolds commanded the 1st Brigade, Brig. Gen. George Meade arrived at Camp Tennally in mid-September to take command of the 2nd brigade, and two months later Brig. Gen. Edward O.C. Ord arrived to assume command of the 3rd brigade.

Although initially refusing Pennsylvania’s additional regiments, in large part due to a personal disdain for Governor Curtin, Secretary of War Simon Cameron authorized the inclusion of the Reserves into the Army of the Potomac on September 16, 1861. Thus, two months after taking their loyalty oath to the commonwealth, the Reserves were mustered into Federal service for three years. In 1864, this conflicting muster-in date proved contentious for the men of the Pennsylvania Reserves as the expiration of their three-year terms neared.

At Camp Tennally, the new recruits endeavored to transition from citizen to soldier. Military reviews offered a welcome break from relentless military drill and gave the rank and file opportunities to catch glimpses of their commanding generals. McClellan garnered enthusiastic cheers, leading one volunteer to declare, “I think we have the right man in the right place.” Other Pennsylvanians shared this optimism. Writing home to his mother, and articulating a naïve expression only possessed by new volunteers, Thomas Dick, a private in the 12th Pennsylvania predicted, “The opinion appears to be here that the war will be ended in the course of six months and then if spared I will return to my quiet home once more.”

For the Pennsylvania Reserves, the pinnacle of their first year came on December 20, 1861, at the Battle of Dranesville. A small village crossroads where the Georgetown Pike and Leesburg Pike converged, Dranesville figured prominently in the operations of both Union and Confederate forces in the war’s early months. Encountering approximately 1,800 Confederates commanded by Brig. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, Ord’s 3rd Brigade, in its baptism of fire, routed the enemy. Not only had the Pennsylvania Reserves recorded their first battlefield victory, but they had also claimed the Army of the Potomac’s initial triumph. “This is the first victory of any account in this part of Virginia,” boasted Adam Bright of the 9th Pennsylvania in a letter to his uncle, “and it was won by the Pennsylvania boys.”

In the spring of 1862, McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign galvanized the nation as the Army of the Potomac moved “on to Richmond” seeking to capture the Confederate capital. After being relegated to the defenses of Washington, in mid-June McCall’s division joined the army’s 5th corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter. Between June 25 and July 1, McCall’s division endured relentless fighting east of Richmond in the Seven Days Battles. Much of the heaviest fighting during that week fell to Porter’s corps and the Pennsylvania Reserves found themselves on the front lines at Mechanicsville, Gaines’ Mill, Glendale, and Malvern Hill. McCall’s division arrived on the Peninsula with approximately 9,500 soldiers and sustained 3,067 casualties, a devastating 32 percent.

In addition to the losses in the rank and file, the fight along the Peninsula decimated the division’s officer cadre. At Gaines’ Mill, Reynolds inadvertently found himself isolated from his brigade, and the following morning was captured by a Confederate patrol. Reynolds remained a prisoner until mid-August 1862 when he was exchanged for Lloyd Tilghman, the Confederate general who surrendered Fort Henry. At Glendale, the division’s third battle in five days, while rallying his infantry, Meade suffered two wounds and spent the remainder of the campaign recovering at his home in Philadelphia. The division’s commander, McCall, was captured in the fight and imprisoned at Libby Prison in Richmond until he was exchanged in August 1862 for Simon Buckner, the Confederate general who surrendered Fort Donelson. McCall returned home to recover, and citing failing health, resigned his commission.

With no time to reorganize, the Pennsylvania Reserves prepared for the 1862 fall campaigns. The Reserves, now commanded by John Reynolds, joined Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia, then positioned at Warrenton, Va., on August 23. Reynolds’ division suffered over 600 casualties in the fight at Second Manassas. Pope praised the Reserves for their conduct during the campaign, noting that Reynolds deserved the “highest commendation” and Truman Seymour and Meade, brigade commanders, “performed their duties with ability and gallantry.”

Following his success at Second Manassas, General Robert E. Lee maneuvered the Army of Northern Virginia into Maryland and, by September 7, had concentrated near Frederick. Meanwhile, elements of Pope’s army were folded into McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, then concentrated near Washington. Now part of General Joseph Hooker’s 1st Corps, the Pennsylvania Reserves departed Washington on September 7 and began marching toward Maryland. Worried that the Confederate push into Maryland threatened his state’s security, Governor Curtin recalled Reynolds to command the state’s militia. Meade assumed command of the division.

As McClellan’s forces maneuvered toward Frederick, on September 14 the Pennsylvania Reserves reached Turner’s Gap, one of the three passes in the South Mountain range. Here, Meade directed an offensive against Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill’s Confederates, over unforgivingly steep, jagged terrain, facing “severe fire across rocks, stonewalls.” Meade later described this as the “most rugged country I almost ever saw.” Still, the Pennsylvanians secured Turner’s Gap, losing 399 men.

On the morning of September 16, Meade’s division approached the small town of Sharpsburg, near Antietam Creek, with, according to the general, no more than 3,000 effectives. Their arrival into the East Woods precipitated a sharp firefight with Confederate skirmishers. At dawn the following morning, with the bulk of their force repositioned in the North Woods, Hooker’s men opened the Battle of Antietam by assailing the Confederate left flank. The fight in the Miller Cornfield quickly evolved into a vortex of death with the Reserves, once again, in the thick of a desperate struggle. When Hooker fell wounded in the fray, Meade assumed command of the corps, and with its units shattered and disorganized, ordered a withdraw. Bloodshed and carnage on the fields at Antietam was unparalleled. Casualties for the Pennsylvania Reserves totaled 573, or 20 percent.

The Pennsylvania Reserves had started the war with a full complement of 15 regiments, or approximately 15,000 men. By the end of the Maryland Campaign, their ranks amounted to little over 2,000. Writing home to his uncle in western Pennsylvania, Adam Bright of the 9th Pennsylvania lamented, “We have lost a good many of our men since I last wrote you.” On September 30, Curtin appealed to Lincoln, requesting that regiments in the Reserves be allowed to return to Pennsylvania, recruit, and then return to the field at full strength. The request was denied; all units were needed on the field. Accordingly, the Reserves experienced another reorganization. With the threat to Pennsylvania eliminated, Reynolds returned to the army, assuming command of the 1st Corps, and Meade again leading the division.

During the Battle of Fredericksburg, December 11-15, 1862, the assault of the Pennsylvania Reserves proved the single bright spot in the otherwise dismal Union outcome. On the morning of December 13, Meade’s division, with now approximately 4,500 infantry, assaulted the Confederate line at Prospect Hill, a position held by Lt. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. Crossing over boggy terrain, Meade’s men directed their assault toward a gap in Jackson’s line. Although the Reserves broke the enemy line, without reinforcements the initially promising assault sputtered as Jackson restored his position. Meade’s men withdrew back over the ground they had just crossed. Furious with a lack of support for his assault, Meade grumbled to Reynolds, “My God, did they think my division could whip Lee’s whole army?”

Once again, the Pennsylvania Reserves had proven themselves as a veteran combat unit. But battlefield heroism invariably came at considerable human cost. Their losses in the fight at Fredericksburg totaled 1,853, roughly 41 percent of their strength. Some within the ranks of the Pennsylvania Reserves interpreted their fight along Prospect Hill at Fredericksburg as frustrating, if not futile. One soldier lamented the lack of reinforcements allocated to Meade’s division, declaring, “Had we been supported we could have taken the heights but our division is too small now to fight the whole rebel army.”

Two years of combat had visibly taken its toll on the Reserves. “You can see that the Pennsylvania Reserves best days are over,” one soldier surmised. Following the Battle of Fredericksburg, Meade received command of the army’s 5th Corps and issued his farewell order to the Reserves promising, “the commanding general will never cease to remember that he belonged to the Reserve Corps.”

Before leaving for his new corps command, Meade advocated that the Reserves return to Pennsylvania for recruitment. He recorded their strength at 195 officers and 4,249 enlisted, but noted that “a very large proportion” of the enlisted strength were wounded and unlikely to return to active duty. In any case, owing to the volume of similar requests from numerous units throughout the army, the War Department again denied the request to return the division to Pennsylvania.

Relief from the front lines ultimately came in February 1863 when the Pennsylvania Reserves were ordered to Washington, D.C. Men greeted the order with much enthusiasm. For the next four months, soldiers maintained the defenses around the capital. By some accounts, however, duty around Washington proved more exacting and tiring than expected. “We have been shamefully treated,” opined one soldier. Despite the harsh winter weather that year, soldiers eagerly took leaves of absences to return home and morale within the ranks slowly improved.

While the Army of the Potomac battled Lee’s forces at Chancellorsville in early May 1863, the Pennsylvanians remained assigned to the defenses of Washington. As Lee extracted his army from Fredericksburg and began moving north, on June 3 the Reserves received a new commander, Maj. Gen. Samuel Crawford. With the 2nd brigade remaining near Washington, the 1st and 3rd brigades joined Meade’s 5th Corps on June 28, the same day that Meade received command of the Army of the Potomac.

At Gettysburg, and fighting now on their native soil, the Pennsylvania Reserves earned further distinction through their deeds on the afternoon of July 2. Texans and Alabamians from Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s First Corps assailed the Federal left flank and a desperate fight for control of Little Round Top ensued. As soldiers from the 5th Corps rushed to secure the army’s left flank, and with bullets whizzing overhead, Crawford led the headlong charge of Colonel William McCandless’ brigade down the northern slope of Little Round Top, scattering the advancing Georgians and South Carolinians under William Wofford’s and Joseph Kershaw’s command. Amid loud cheers, the Pennsylvanians “charged at a run down the slope driving the enemy back.”

Crawford’s countercharge swept the enemy from their front, through the marshy Plum Run, and back into the Wheatfield. That evening, McCandless’ regiments held their position along a stone wall at the eastern border of the Wheatfield. The following day, after the Union repulse of Pickett’s Charge, the Pennsylvania Reserves advanced across the Wheatfield, assailing the 15th Georgia, and cleared the enemy from Rose Woods. Totaling no more than 3,000 effectives, Crawford’s two brigades counted 210 casualties during the Gettysburg Campaign. Once again, in two days of action at Gettysburg, the Pennsylvania Reserves had proven steadfast.

After the Gettysburg Campaign came to a close, Meade’s army maneuvered against Lee’s forces in Virginia into the fall of 1863. That winter, as the expiration of their initial three year terms of service loomed, the War Department incentivized reenlistment for an additional three years, or the duration of the war. Of the approximately 4,300 soldiers now in the ranks of the Pennsylvania Reserves, roughly 1,700 men reenlisted.

As the spring campaign season neared, the men from the Pennsylvania Reserves eagerly anticipated their return home, believing that their three-year term of service would be fulfilled in May. The 9th Pennsylvania’s term of service expired on May 4; the regiment reached Pittsburgh and mustered out of service on May 13. For the soldiers in the remaining infantry regiments, now organized into two brigades, the war continued.

Back in Pennsylvania, Governor Curtin had appealed to the War Department to uphold the May termination date, but the administration denied the request. Invariably, unrest mounted among the rank and file. “The impression is now,” one soldier griped, “that we will not be discharged before the middle of July.” The division’s muster-out date loomed and in their final month of service to the Union cause the reserves would witness some of the most desperate fighting they had yet to see. As the Overland Campaign began in early May, the Pennsylvania Reserves saw combat during the fight in the Wilderness. On the morning of May 12, at Spotsylvania, they made a futile charge against the Confederate earthworks at Laurel Hill, “driven back each time with heavy loss.” As the Army of the Potomac continued to grind against Lee’s forces, so too did the Pennsylvania Reserves, fighting at Guinea’s Station, North Anna River, and Bethesda Church.

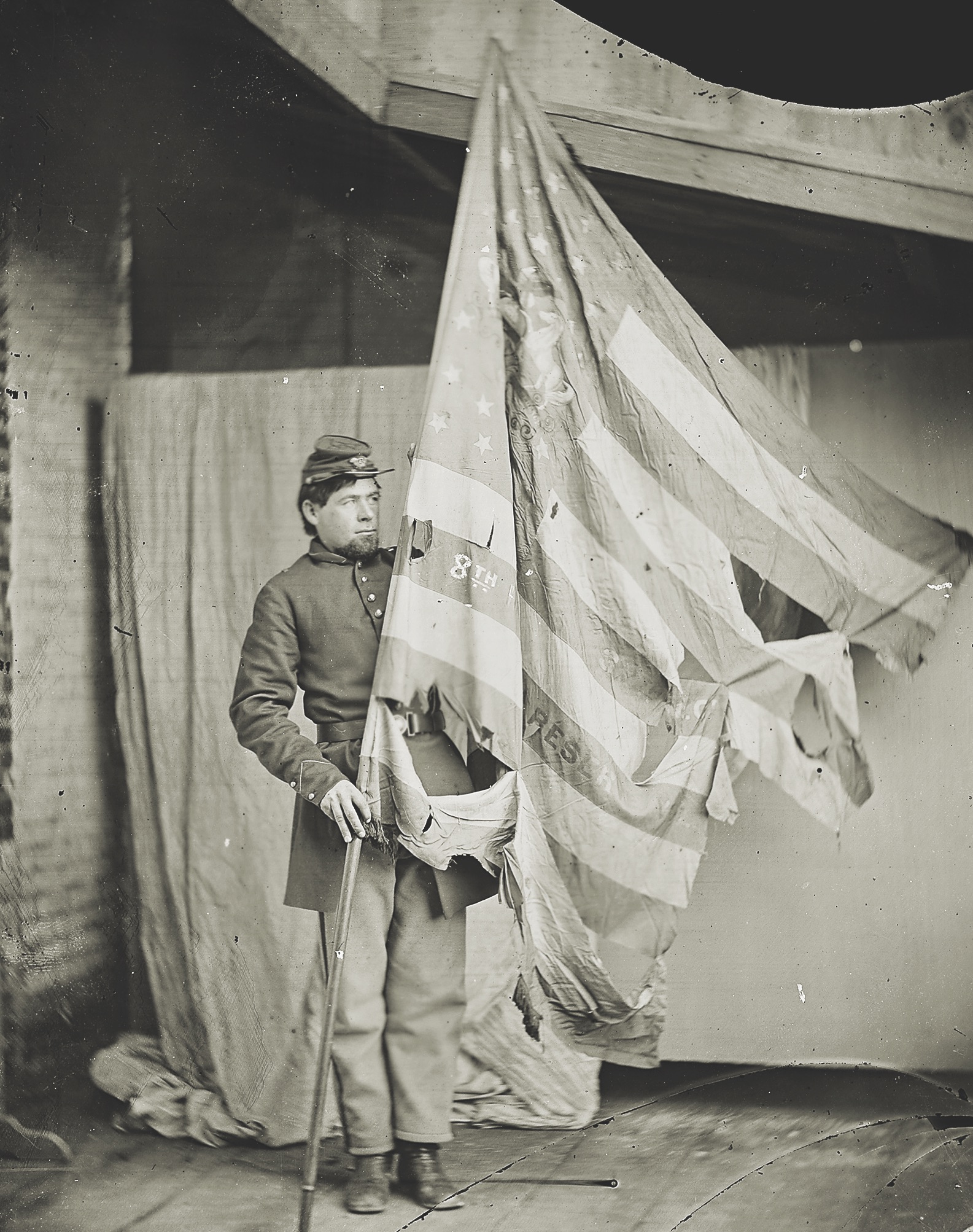

Finally, on May 31, 1864, Maj. Gen. Gouvernor K. Warren issued orders for the Pennsylvania Reserves to return home. Their service to the Union was complete. In his farewell order, Warren acknowledged the valor of the division, declaring, “great satisfaction at their heroic conduct in this arduous campaign.” In expressing gratitude at their three years of distinguished service, Crawford extolled, “Take back your soiled and war-torn banners, your thinned and shattered ranks, and let them tell how you performed your trust.”

Soldiers of the “thinned and shattered ranks” wearily boarded transports at White House Landing, and began arriving in Harrisburg on June 6. Josiah Sypher, writing the history of the Pennsylvania Reserves, reported that approximately 1,200 officers and men returned to the Commonwealth and were mustered out of federal service. Regiments that had marched off to war in the summer of 1861 with robust ranks returned home as shadows of their former selves, with men indelibly transformed by the carnage of war. The 11th Pennsylvania, for instance, mustered out a mere 211 men. Yet the war did not come to an end for all soldiers in the Pennsylvania Reserves. Indeed, the soldiers who reenlisted in December 1863 were reorganized into the 190th and 191st Pennsylvania and participated in the war’s final campaigns.

Over four grueling years, the Pennsylvania Reserves played a prominent role in the campaigns of the Army of the Potomac. Soldiers of the Pennsylvania Reserves recorded one of the most distinguished combat records of any division in the Civil War’s armies. This division produced some of the finest generals in the Union Army, John F. Reynolds, Edward O.C. Ord, and George G. Meade. From Dranesville through the Overland Campaign, these men were often in the thickest of the fight, suffering consistently high casualty rates in their service to the Union. “The memory of the dead will be more sacred, and the names of the living more honorable,” extolled the division’s historian, “because they are enrolled as Pennsylvania Reserves.” Indeed, the Pennsylvania Reserves deserve a prominent place on the mantel of legendary Civil War units.

Jennifer M. Murray is a military historian at Oklahoma State University. Murray’s most recent publication is On A Great Battlefield: The Making, Management, and Memory of Gettysburg National Military Park, 1933-2013, published by the University of Tennessee Press in 2014. She is currently working on a full-length biography of George Gordon Meade, tentatively titled Meade at War.