All through the sweltering night of Aug. 30, 1813, beneath a dim crescent moon, Red Eagle had quietly mobilized upward of 700 warriors in the tall grass around “Fort” Mims—certainly an exaggerated designation for the flimsy stockade surrounding the blockhouse, cabins and barns of wealthy planter Samuel Mims. In Creek country some 40 miles northeast of Mobile, Mississippi Territory—in what would soon become Alabama Territory—Mims’ stronghold had become the only place of refuge for American settlers, their slaves and their mixed-blood Creek friends after war had erupted in the summer of 1813 between the Upper Creeks and the United States. On being defeated by the Creeks farther east at Burnt Corn Creek that July 27, territorial militiamen had retreated in disarray, leaving the Alabama frontier defenseless.

Major Daniel Beasley had but 140 militiamen under his command to protect the nearly 300 refugees crammed into the 1-acre stockade. The major was remarkably casual concerning the peril they faced. When warned by a slave on August 29 about an approaching Creek war party, he dismissed the report and had the poor man tied to a post in the middle of the stockade and flogged. The next day when Red Eagle sent his warriors storming forward at noon—surprising the defenders during their midday meal—Beasley was among the first to fall as he moved to close the gate he had so carelessly allowed to be left open. The settlers retreated into the larger cabins and set up a stiff defense, but Red Eagle had his warriors unleash a torrent of flaming arrows on them. Those who fled outside were quickly clubbed to death, while the rest were burned alive. Red Eagle reportedly tried to halt the slaughter, but he found it difficult to restrain his warriors. He managed to protect only a few dozen slaves and a handful of women and children, while the Creeks razed the fort and tortured captured soldiers to death. It was all over by late afternoon.

That day of horror marked the most decisive victory by the Creeks in their war with the Americans. It also made their mixed-blood leader, Red Eagle—or Lamochattee in Creek, also known by his English name, William Weatherford—among the most infamous of all Indian chiefs. Red Eagle’s father was Scot fur trader Charles Weatherford, his mother Sehoy, Creek half-sister of mixed-blood soldier-statesman Alexander McGillivray, former principal chief of the Upper Creeks. Sehoy’s status in the prominent Wind Clan placed her son, born circa 1780, into a natural leadership position in the Creek’s matrilineal society.

The Creeks, whose villages spanned the region comprising present-day Alabama and southwest Georgia, had fought alongside the British in the American Revolution and remained allied with them as trading partners after the war. Both the British and Spanish in Florida supplied the Upper Creeks—whose villages lay to the northwest along the Alabama, Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers and their tributaries—with trade goods and eventually arms with which to resist the American advance into their region. Concerns about these foreign intrigues with the Creeks led U.S. troops under General James Wilkinson to formally claim Spanish territory in Florida west of the Perdido River in December 1813. Most Lower Creeks—who lived farther east and south along the Chattahoochee, Ocmulgee and Flint rivers—under their mixed-blood leader William McIntosh (Red Eagle’s cousin), allied with the Americans. Thus when war broke out with the Americans in the summer of 1813, it spawned a civil war among the Creeks. McIntosh, who would fight alongside General Andrew Jackson at Horseshoe Bend, was later assassinated for his fealty to the Americans.

Red Eagle had fallen under the spell of Shawnee Chief Tecumseh’s call for pan-Indian resistance to the American advance. Although only one-quarter Indian, Red Eagle had risen to prominence as a leader of the Upper Creek Red Stick faction—named for their war clubs with red-painted handles—after Tecumseh’s 1811 recruiting tour to the Choctaws, Cherokees and Creeks. The great Shawnee won over many Creeks to his visionary cause. American agents had long pressured the Creeks to abandon their ancestral habits and adopt agriculture as a new way of life. Such a shift would free up their hunting lands for the government to sell to new settlers (land sales were critical to the funding of the nascent republic). A new federal road linking Washington and New Orleans soon pushed through the heart of Creek country, and thousands of settlers followed it southwestward. That further increased tensions between the Upper and Lower Creeks, in turn attracting impulsive young warriors to Tecumseh’s bold plan for an Indian confederacy. In May 1812 a party of Red Sticks under Little Warrior murdered settlers on Tennessee’s Duck River, and in February 1813 Little Warrior again led Red Sticks on a murder raid, slaughtering settlers along the Ohio River. To appease the Americans, the Creek National Council had McIntosh track down and execute Little Warrior and several of his men. When the Upper Creeks retaliated by killing some of McIntosh’s men, the die was cast. The Red Sticks then began a calculated campaign of assassination against chiefs allied with the Americans. Thus began the Creek War.

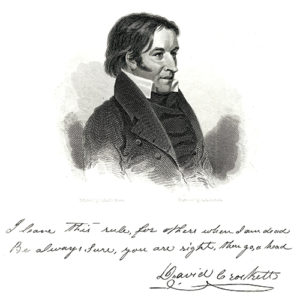

‘The truth is, my dander was up,’ Crockett later reflected, ‘and nothing but war would bring it right again’

Tennessee militia Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson, particularly outraged by the May 1812 Duck River killings, immediately wrote Tennessee Governor Willie Blount, insisting the Creeks “must be punished, and our frontier protected, and I have no doubt but they are urged on by British agents and tools, the sooner they can be attacked, the less will be their resistance.” He requested 2,500 volunteers and permission to advance “and lay their towns in ashes.” Blount initially refused Jackson. But when the United States declared war on Great Britain the following month, the governor relented. Militia Maj. Gen. Jackson became U.S. Volunteers Maj. Gen. Jackson and began to recruit his army. The grim news from Fort Mims proved a great boost to recruitment.

When news of the Upper Creek massacre at the fort reached the Tennessee settlements, young Davy Crockett was among the first men on the recruiting lines. Crockett enlisted at Winchester on Sept. 24, 1813, as a 90-day volunteer in Captain Francis Jones’ company of Tennessee Volunteer Mounted Riflemen. He left wife Polly and their young children at his small farm 10 miles south of Winchester. She begged him not to go, but he was determined. “My countrymen had been murdered, and I knew that the next thing would be, that the Indians would be scalping the women and children all about there, if we didn’t put a stop to it,” he recalled in his memoir. “The truth is, my dander was up, and nothing but war would bring it right again.”

Jones’ company marched to a rendezvous point just south of newly settled Huntsville, where they joined with other mounted militia companies as part of Colonel John Coffee’s cavalry division, more than 1,000 strong. General Jackson was not yet with them, for he had been terribly wounded in a September 4 Nashville brawl with brothers Jesse and Tom Benton, in which Coffee had come to his defense. Jackson lay near death for several days, his left arm rendered useless by Jesse Benton’s pistol shot (he would carry the ball in his shoulder for 20 years before finally having it removed by surgeons in Washington when he was president), and he remained bedridden for weeks. Not until month’s end would he head south to join Coffee’s advance guard.

While waiting, Coffee decided to send a scouting party under Major John Gibson across the Tennessee River, and the colonel asked Captain Jones for the best woodsman in his company. Jones selected Crockett. Crockett brought young George Russell with him, and the party soon set off for Upper Creek country. The major split the group, sending Crockett and five others scouting south to the Coosa, where they discovered large numbers of Red Sticks moving north. Crockett and his men rode all night to inform Coffee. To the frontiersman’s chagrin his report made little impact on the colonel.

“When I made my report, it wasn’t believed, because I was no officer; I was no great man, but just a poor soldier,” he recalled. “But when the same thing was reported by Major Gibson! Why, then, it was all as true as preaching, and the colonel believed it every word.…It convinced me, clearly, of one of the hateful ways of the world.”

Coffee sent a message by express rider to Jackson at Fayetteville, Tenn., to hurry south with his infantry, and the general reached Coffee on October 24 at Camp Deposit on the Tennessee River. Jackson soon learned of an Upper Creek force at nearby Tallushatchee and promptly ordered out Coffee with 900 men to attack them. Before dawn on November 3 Coffee’s men surrounded the Creek village. A number of women and children came forward to surrender, but as they were being helped to the rear by soldiers, several warriors suddenly opened fire. The volunteers returned a devastating fire on the Indians. “We now shot them like dogs,” recalled Crockett with dismay of a battle that soon devolved into a massacre.

After nearly 50 warriors took shelter in a wooden house, the volunteers—no doubt with Fort Mims in mind—set it ablaze and burned the Creeks alive. The next day, as soldiers sifted through the ashes in that same charred house, they discovered a potato cellar. Crockett and the other famished men soon crawled down into it. “We found a fine chance of potatoes in it, and hunger compelled us to eat them, though I had a little rather not,” Crockett wrote, “for the oil of the Indians we had burned up on the day before had run down on them, and they looked like they had been stewed with fat meat.”

The grim moment, related in searing detail in Crockett’s 1834 autobiography, left him feeling, in both a real and metaphorical sense, that the pioneers were drawing sustenance from the Indian dead—cannibalizing them to build a new nation. (In May 1830 Congressman Crockett would rise on the floor of the U.S. House on Representatives to denounce President Andrew Jackson’s notorious Indian Removal Bill, a position that helped doom Crockett’s political career.)

Within days word reached Jackson that Red Stick warriors were besieging the Lower Creeks at Talladega, and Crockett soon rode south with Coffee’s command to rescue their Indian allies. At least 1,000 Red Sticks encircled the Talladega stockade. They were in turn surrounded by Jackson’s 1,200 infantry and 800 mounted riflemen. In the bloody battle that followed on November 9 the soldiers killed more than 300 Red Sticks before the rest managed to break through the militia lines and flee. Jackson, with but 15 dead, might have pursued and crushed the Upper Creeks had he not run out of supplies. With his troops facing starvation and talk of mutiny spreading among both the militia and volunteers, Jackson had no choice but to retrace his steps to Camp Deposit. He ordered Coffee’s mounted volunteers back to Tennessee to refit and get fresh horses, while he remained to face down his increasingly insubordinate militiamen. Crockett happily returned to Polly and his children and, along with all the other volunteers, refused to return when recalled by Coffee, as they had less than two weeks left to serve. Paid $65.59, he was discharged on Christmas Eve.

Jackson lived up to his hard-nosed nickname “Old Hickory” in those trying days of December 1813 and January 1814 as he dealt with a total breakdown of logistical support, mutinous troops and the absence of promised reinforcements from Blount. He overcame every obstacle through dogged determination and was finally rewarded on January 14 when 850 recruits reached him at Fort Strother. Without hesitation the flinty general immediately marched the green soldiers into Creek country, where he seasoned his troops and bled the enemy in two indecisive battles, at Emuckfau and Enotachopco creeks. The Americans, with nearly 100 casualties (including Coffee seriously wounded and Jackson’s nephew Alexander Donelson killed), retreated back to Fort Strother. At that dark moment in Jackson’s fortunes came a sudden turnaround. On February 6 the 39th U.S. Infantry under Colonel John Williams reached the fort. Among the ranks of that regiment of Regulars was young Ensign Sam Houston—future founding president of the Republic of Texas. Soon joining the growing force were more Tennessee volunteers sent south by Governor Blount, as well as 500 Cherokees under Chief Major Ridge and 100 Creeks under McIntosh. With his ranks swelled to more than 5,000 men, Jackson felt confident enough to advance against the main Red Stick village at Tohopeka, on the Horseshoe Bend of the Tallapoosa River.

Commanding the Upper Creeks at Tohopeka was Menawa (Great Warrior), supported by Red Eagle and several other chiefs and prophets (spiritual leaders). More than 300 of their cabins dotted the peninsula enclosed by the bend in the river. A nearly 400-yard-long dirt and log barricade spanned the gap on the land side of the village, while the river protected its flanks. Here the Creeks had gathered more than 1,000 warriors and some 400 women and children. They felt confident their breastworks and the river would protect them from their enemy.

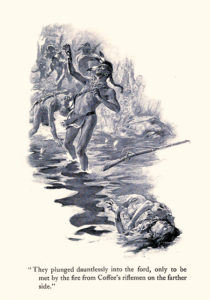

Jackson approached Horseshoe Bend on the morning of March 27 and promptly opened fire on the stout log barricade with his artillery battery (a 6-pounder and a 3-pounder), but the small cannons had little impact. Meanwhile, he sent Coffee and his 700 horsemen, along with the 600 allied Indians, to cross the Tallapoosa below the bend and surround the peninsula to prevent any escape. On hearing the opening artillery barrage, several of the allied Indians swam across the river on their own initiative to seize the Red Sticks’ canoes. After paddling back to the far bank, they began to ferry men across to attack the village from the rear while Coffee’s men provided covering fire. Within minutes 300 Indians had crossed and were engaged in sharp fighting with the defenders. They set the Creek cabins on fire, and under this smokescreen more of Coffee’s men crossed to join the fray.

Jackson, hearing the gunfire and seeing the plumes of smoke, ordered the long roll sounded and sent his 2,000 infantrymen forward at 12:30 p.m. The Regulars took the lead, supported by the militia. They were met by a brisk fire from the barricade. Major Lemuel Montgomery of the 39th was the first to mount the barricade, only to be shot dead. He was followed by Ensign Sam Houston, who, despite taking a barbed arrow to his thigh, dropped into the fort and cut down several Creeks with his saber. As other soldiers poured over the barricade, the young ensign reluctantly retired to seek a surgeon. Jackson rode up as Houston was being treated. Inquiring into the ensign’s condition, Jackson ordered Houston not to return to the fray. The exchange marked the beginning of a warm friendship that would forever alter the destiny of the American West.

The Red Sticks, though outnumbered and outgunned, disdained surrender and fought tenaciously. Twice Jackson offered quarter, only to be met by musket fire. Limping back into battle, Houston led a charge on a Creek redoubt and was wounded twice more. “Not a warrior,” he recalled, “offered to surrender, even while the sword was at his breast.” A severely wounded Menawa hid beneath a pile of dead warriors until he could slip into the river and escape. He was among the few to survive, for the soldiers and their Indian allies slew upward of 800 Creek warriors at Tohopeka before darkness stopped the killing. Most all of the Indian families were taken captive, Jackson deeply regretting the deaths of a handful of women and children. Of the 350 captives, however, only three were warriors. Jackson’s losses totaled 26 killed and 107 wounded among his Regulars and militia, 18 killed and 36 wounded among Ridge’s Cherokees, and five killed and 11 wounded among McIntosh’s Creeks.

‘He possessed in a most preeminent degree,’ Jackson later wrote of Red Eagle, ‘the elements of true greatness and for reckless personal courage was the Marshal Ney of the Southern Indians’

The decisive victory at Horseshoe Bend had ended the Creek War, at the same time denying the British the Indian allies they needed to assist in a planned invasion. But Jackson was not satisfied. He wanted Red Eagle, and after the battle his scouts combed the forest for the Red Stick leader. Captured Upper Creeks were offered bounties to betray their leader to the Americans, and Jackson made it clear there could be no peace until Red Eagle was killed or captured. What Jackson didn’t know is that two days before the battle his prey had left Tohopeka for Hoithlewalee to gather more warriors.

On December 18 a solitary Indian rode into the American camp near the confluence of the Coosa and Tallapoosa. He was not molested as he guided his gray stallion toward Jackson’s tent, for despite his Creek garb he had long red hair and sunburned skin and was thought to be a scout. As Red Eagle reined in his horse before Jackson’s large tent, Creeks allied with the Americans finally did recognize him. When Jackson emerged from his tent, Red Eagle gave an eloquent speech, offering up his life if only Jackson would spare the starving Red Stick families. Moved, Jackson shouted down the mob that had gathered to lynch the prisoner. “Any man who would kill as brave a man as this would rob the dead!” the general declared.

Recognizing a kindred spirit, Jackson invited the captive warrior into his tent. “He possessed,” the general later wrote “in a most preeminent degree the elements of true greatness and for reckless personal courage was the Marshal Ney of the Southern Indians.” Thomas Woodward, who witnessed the surrender, later wrote, “General Jackson, as if by intuition, seemed to know that Weatherford was no savage and much more than an ordinary man by nature and treated him very kindly indeed.” Red Eagle agreed to bring in as many of his warriors and their families as possible, as well as to secure the release of white and black American captives. When Jackson returned to his Tennessee estate, he brought along Red Eagle, to protect the Red Stick leader from retribution.

The return of the heroes from Horseshoe Bend encouraged Crockett to rejoin the volunteers. With the Creeks defeated, word was the Tennesseans would travel to the Gulf Coast to take on the British. “I wanted a small taste of British fighting,” Crockett recalled. On September 28 he enlisted in Major William Russell’s Tennessee Mounted Gunmen and was promptly promoted to sergeant. Russell’s command of 130 men hurried south from Fayetteville to join General Jackson’s force, then advancing on Pensacola. Jackson, who’d been rewarded with a commission as a major general in the Regular Army and placed in command of the 7th Military District, was charged with halting any British attack on the Gulf Coast. By the time Russell’s men arrived on November 8, Jackson had taken Pensacola, and Crockett and the newly arrived troops had only the solace of witnessing the departure of British ships from the harbor. Crockett’s company was then sent into the Florida swamps in search of recalcitrant Red Sticks and their Seminole allies. Though they saw some fighting, their greater adversaries were swamp fever and meager rations. Crockett’s hunting skills were certainly much in demand. He returned home to Polly and his children in February, hiring a young friend to serve out the remaining month of his enlistment. “This closed my career as a warrior,” he later wrote, “and I am glad of it, for I like life now a heap better than I did then.”

When the War of 1812 ended in a blaze of glory with Jackson’s stunning victory at New Orleans on Jan. 8, 1815, Red Eagle returned to Alabama to rebuild his fortunes. As William Weatherford, he became a prosperous American planter, with hundreds of acres under cultivation by some 200 slaves. His children married into some of the best Alabama families. Weatherford died in 1824, just as his friend Jackson launched his presidential campaign, and was buried to the west of Little River under a stone marker erected by admiring Anglo neighbors. By then Crockett was in the Tennessee General Assembly. In 1827 he won election to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Jackson supporter, though during his three terms in Congress he came to oppose the president on several issues, the most contentious being the question of Indian removal. His experiences in the Creek War haunted him, prompting his strong objection to the Indian Removal Bill. That in turn led to his 1835 electoral defeat, his departure for Texas, the Alamo and immortality. MH

Paul Andrew Hutton is a distinguished professor of history at the University of New Mexico. His most recent book is The Apache Wars (2016), and he is writing The Undiscovered Country, a history of westward expansion featuring Davy Crockett and Red Eagle, among others. For further reading Hutton recommends A Paradise of Blood: The Creek War of 1813–14, by Howard T. Weir III, and Battle for the Southern Frontier: The Creek War and the War of 1812, by Mike Bunn and Clay Williams.

This story was published in the October 2016 issue of Wild West. For more stories, subscribe here.