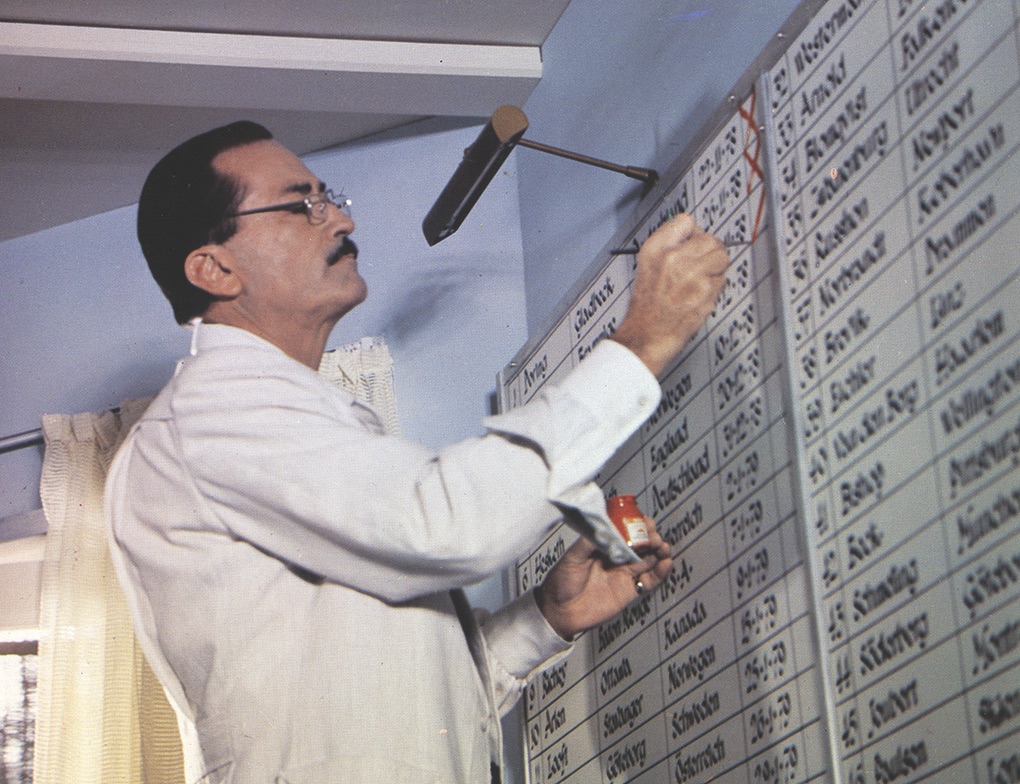

The Boys from Brazil (1978) stars Gregory Peck as Dr. Josef Mengele, biding his time in South America with plans to replicate Adolf Hitler and launch a Fourth Reich.

The name Adolf Hitler is synonymous with absolute evil, so much so that Jewish theologian Emil Fackenheim once called him “an eruption of demonism into history.” The success of The Boys from Brazil depends upon the audience’s willingness to go along with this assessment—and enough of them did to make the film a box office hit when it reached theaters in 1978.

Directed by Franklin J. Schaffner and adapted from author Ira Levin’s 1976 novel of the same name, The Boys from Brazil takes place three decades after Hitler’s 1945 bunker suicide beneath the Nazi Chancellery. A “Comrades Organization,” a cabal of surviving SS officers based in South America, is intent upon creating a Fourth Reich. To do so, they must assassinate 94 middle-aged men—all of them minor civil servants—and these killings must fall within a day or two of certain dates. The assassins themselves are ignorant of the reasoning behind the scheme. Only those at the very top of the Comrades Organization know the true plan, and among them all, perhaps the only one who fully believes in it is Dr. Josef Mengele (played by Gregory Peck), notorious for his fiendish experiments on Auschwitz inmates. He seeks nothing less than to create a duplicate of Hitler, with the fanatical certainty that this Hitler will save the Aryan race in the latter years of the twentieth century.

Mengele has produced 94 Hitler clones, made from DNA collected from the dictator in May 1943, and placed the infants with adoptive parents, in which the fathers are all precisely 52 years old and the mothers are 29, replicating the age of Hitler’s parents at his birth. Between the age difference and the fact that the fathers of the cloned Hitlers are all minor civil servants—Hitler’s father was a customs official—Mengele believes that this will suffice to replicate Hitler’s family environment: a domineering father, a doting mother. He estimates that with 94 such attempts, this combination of nature and nurture will produce at least several boys identical to the Nazi leader. The chief complication is that Hitler’s father died at age 65, shortly before Adolf’s 14th birthday. Thus, if the experiment is to succeed, his death, too, must be replicated; hence the mandatory killings.

Early in the film, Jewish Nazi hunter Ezra Lieberman (played by Laurence Olivier) discovers that Mengele has ordered the assassinations of 94 men in countries across northern Europe and in North America. He doggedly pursues this mysterious clue without knowing where it will lead. But while visiting several of the murdered men’s widows, he makes a startling discovery: each has a 13-year-old boy (all played by Jeremy Black) with similar features: pale skin, piercing blue eyes, and a spoiled, disagreeable manner. Eventually, with the help of a geneticist, Lieberman discovers that they must be clones—clones of the Nazi dictator, he deduces—which leads to a climactic confrontation with Mengele in the home of one of these budding Hitlers.

Before he wrote The Boys from Brazil, Levin produced a similar novel: Rosemary’s Baby, published in 1967 and adapted to film by director Roman Polanski a year later. Considered one of the top five horror movies of all time, Rosemary’s Baby centers on a young wife who is unwittingly impregnated with Satan’s son. The Boys from Brazil shares much of the same theme: Hitler is commonly perceived as humanity’s closest answer to the devil incarnate, and, according to the movie, recreating that evil would be as simple as placing a biological carbon-copy of the dictator in a likewise duplicated family.

This concept ought to be laughable. Logically, Hitler was a product of his time, place, and culture: he rose from a minor political party gestated by a Germany mortified by its loss to the Allies in 1918 and achieved political power through a single-minded attempt to dismantle the humiliating Versailles settlement. Neither Mengele nor anyone else could recreate these conditions, nor the dozens of other factors necessary to concoct the Hitler who conquered Europe and launched the Holocaust. All Mengele and his minions could possibly have accomplished would be to create a failed, narcissistic artist—which is all Hitler would have been but for the titanic historical forces that made him infamous.

And yet, when Hitler is concerned, we are not logical. For most of us, Hitler does indeed seem like “an eruption of demonism into history.” The Boys from Brazil chilled audiences because they implicitly believed this. So do most of us. To be anything else, Hitler would have to be a human being, just like ourselves. And that is something we find truly intolerable. ✯

This article was published in the October 2021 issue of World War II.