Sergeant Harrison Wells of the 13th Georgia passed through the Potomac River Valley region with General Robert E. Lee’s army in 1862 and 1863. Writing to his fiancée Mary “Mollie” Long during the 1862 Maryland Campaign, Wells described the “dark and deep” Potomac River, the pastoral countryside, and the area’s quaint villages. For Wells, the sublime supplanted any signs of war. Less than a year later, however, on June 20, 1863, he found himself in familiar country, and now signs of war were everywhere. Camped near Shepherdstown, W.V.—the site of sharp fighting on September 20, 1862, at the conclusion of the Maryland Campaign—the surrounding trees were “considerably lacerated by the shot & shell.” Wells grimly continued: “Here’s where the river was almost damed with their dead, and we can see some of their bones now, where they were dashed over the precipice this side of the river.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The Potomac Valley’s resources attracted raiders bent on destruction[/quote]

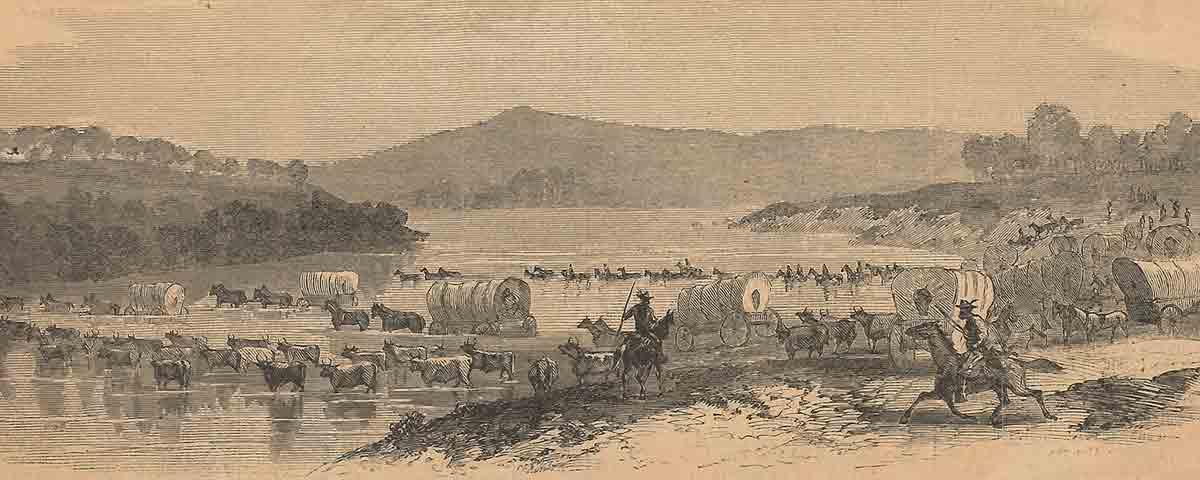

A borderland between two warring nations, the Potomac Valley’s vast natural and manmade resources—including the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, fertile fields, bountiful crops, innumerable livestock, and grain mills—attracted ragged and starved soldiers, commanders desperate for supplies, and raiders bent on destruction. Large parts of the war’s Eastern Theater witnessed fierce but quick collisions between the two great armies, but soldiers and raiders were a constant presence in the Potomac Valley because of the area’s strategic importance and natural vulnerability.

Areas such as Loudoun County, Va., were “debatable ground,” as one resident proclaimed, through which Union and Confederate troops constantly traveled. Catherine Broun, who lived in Middleburg, Va., wrote in her diary: “We expected to be surrounded by yanks this morning but instead of them a number of White’s Batallion came up and enquired for breakfast[.] I have been feeding them all day.” The contested nature of this region dissolved boundaries between states and Union and the Confederate territory, as soldiers, slaves, partisans, and civilians indiscriminately crossed through the region.

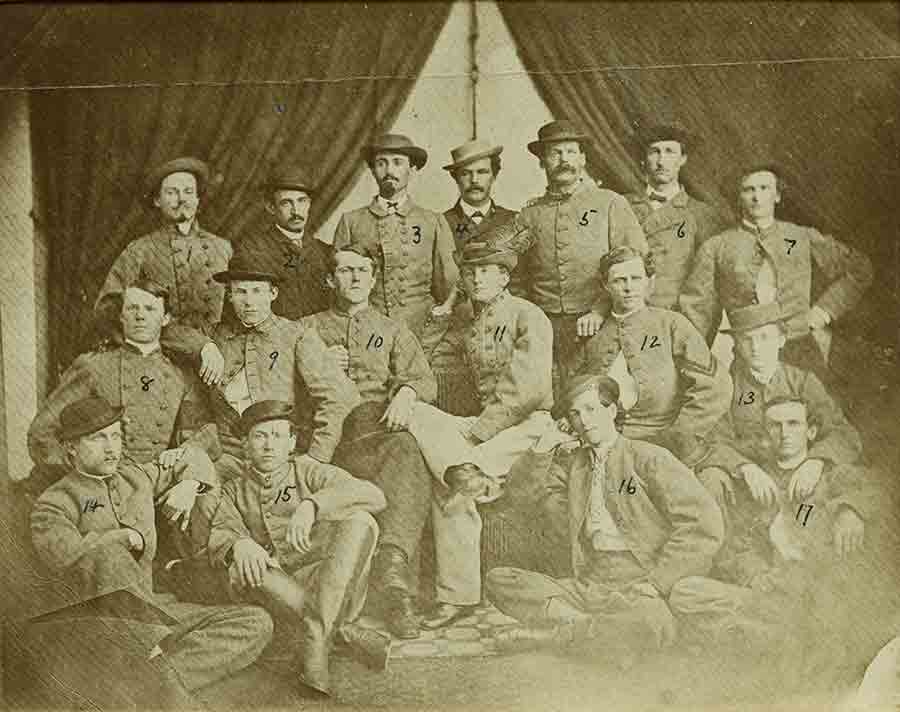

Beginning in the spring and summer of 1861, Union troops spread across Maryland’s southern border guarding river crossings, protecting the C&O Canal and the B&O Railroad, and securing lines of communication. Units such as the 13th Massachusetts, which hailed from Boston and included many affluent and educated soldiers, began their military service along the Potomac River. Over time, the Massachusetts troops fell into a familiar routine that included stints on picket duty, the predictable schedule of military life, and occasional trips along the C&O to move their base of operation.

Yet Confederate forces maintained a careful watch over Maryland’s southern border and frequently harassed Federal pickets, destroyed canal boats and rail lines, and cut communication. In September 1861, Confederate Ass. Adj. General R. H. Chilton informed Colonel Turner Ashby that it had been the Confederate government’s objective “to destroy the canal at any point where it could not be repaired.” Chilton asked that Ashby channel his energies toward the mouth of the Monocacy River, site of the largest aqueduct on the C&O, where the damage “would be irreparable for an indefinite period.”

Drain the Ditch

In this 1864 Harper’s Weekly engraving, Confederates have just cut the earthen berm of the C&O Canal to drain the ditch of its water. In a September 15, 1862, issue of his paper, a New York Tribune reporter described damage done to the canal during the Army of Northern Virginia’s first advance north of the Potomac River:

“Commencing five miles below Monocacy, continuing up a mile beyond the Point of Rocks, in crossing, they tapped the canal at five different places. Several flood-gates were hewn to pieces, and from the heights above, large boulders of rocks were dislodged and thrown into the basin….For the present from 20 to 25 miles of the canal are rendered useless, and in the meantime boats can proceed only between Georgetown and Seneca. The latter place is about 45 miles from Harper’s Ferry. The canal basin is perfectly dry in many places, between those points, and where the water remains it is not more than a foot deep.”

Ashby had been carefully monitoring the canal, noting the presence of Union pickets from the 28th Pennsylvania and the 13th Massachusetts and the transportation of coal and other supplies. Instead of focusing on the Monocacy region, the cavalier [Ashby] launched an attack at Dam No. 4, below Williamsport, Md., which heavy rains ultimately hampered. While Ashby’s concentrated assault was unsuccessful, his troops did prove themselves a considerable nuisance.

Discussing the fall of 1861, one of Ashby’s horsemen, Marylander Harry Gilmor, recounted: “While encamped near Morgan’s Spring, parties, of which I was generally one, would be sent frequently to the Potomac for the purpose of blockading the canal on the Maryland side, by which immense supplies of coal and provisions were brought to the capital.” The troops made good use of terrain and environmental features to conceal their position. “We would go down before daylight,” Gilmor wrote, “conceal ourselves behind rocks or trees, or in some small building, and when the sun was up, not a soldier or boat could pass without our taking a crack at them, and generally with effect, for we were all good shots.” The men became a “perfect pest” and a formidable presence.

Throughout 1861 and 1862, Southern soldiers targeted supply and communication lines as well as Federal garrisons in the Potomac Valley. By 1863, the region had become war-torn. Not only did the landscape bear the marks of battle but local farmers had plenty to protest as Union and Confederate troops consumed livestock, destroyed fencing, and felled trees. West Virginian Anna Stipes, for instance, compiled a litany of complaints in her petition to the Southern Claims Commission charging that soldiers took all the family’s meat one year and 11 hogs in another. To cook this food, of course, soldiers needed fires, and all along the Potomac River troops hauled off fence rails and toppled wooden structures. Samuel Young, a farmer near Edwards Ferry, wrote in disgust that troops had destroyed the fencing that kept his hogs and cattle from crossing the C&O.

Small-scale operations conducted by Confederate partisans and raiders continued in 1863, as well as a second invasion by Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. The Rebel advance into Maryland and Pennsylvania is often considered only within the confines of his main army’s push from Shepherdstown to Williamsport but the Confederate front extended across large swaths of the Potomac Valley. Even before Lee’s army had entered Maryland, John S. Mosby and his 43rd Battalion, Virginia Partisan Rangers (raised in Virginia’s Loudoun and Fauquier Counties) crossed the Potomac River at Seneca Ford and attacked a Union command post along the C&O to destroy vital war material. Mosby’s short, fierce raid of June 10, 1863, presaged a series of actions directed at Federal posts along the Potomac Valley during the 1863 campaign season.

The partisan raids and cavalry attacks of early-to-mid June distracted Federals from the movements of Lee’s main army. Elijah V. White’s 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry, drawn primarily from Loudoun County, played a vital role in disrupting lines of communication and transportation. White targeted Point of Rocks, Md., for a raid that, “much like that carried out by Mosby to Seneca, would also sow further confusion among the Yankees and divert attention from the main Southern advance,” writes Taylor M. Chamberlin and John M. Souders in Between Reb and Yank: A Civil War History of Northern Loudoun County, Virginia. His party traveled down the C&O’s towpath, moving toward Point of Rocks before nightfall; once there, the Confederates attacked a small Federal command of Cole’s Maryland Cavalry (1st Md. Potomac Home Brigade Cavalry) and the Loudoun Rangers. Outnumbered and overpowered, the Union troops succumbed quickly.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Confederate attacks throughout the summer and fall of 1863 proved financially detrimental[/quote]

White captured a large number of men, a train of cars, and a number of wagons; both baggage and camp equipage were burned. Farther west at Cumberland, Md., Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden initiated an assault on the Federals after Lee had instructed him to inflict “all the injury in your power by striking them a damaging blow at any point where opportunity offers.” On June 17 (concurrent with White’s assault at Point of Rocks) Imboden’s party arrived south of Cumberland, drove away Federal patrols, and then shelled the town. The Confederates asked for and were granted the town’s surrender. The Southern soldiers occupied Cumberland for several hours, but did little damage according to a Union officer.

Well after Lee’s army had safely recrossed the Potomac at Williamsport in the middle of July 1863, the Potomac Valley remained an active front. Significantly, Confederate guerrilla and partisan troops continued to present a threat to the B&O, the C&O, and nearby Union garrisons. Canal boats once again began moving slowly along the eastern end of the C&O in July, as crews mended the physical damage from the Confederate’s summer invasion. By August 13 the Civilian & Telegraph of Cumberland happily reported that navigation “upon the Canal has been resumed, and boats are now running. A heavy business will be done upon the canal during the remainder of the season should there be no interruption to boating.”

But Confederate raiding parties quickly brought on interruptions. The canal’s renewed commerce immediately attracted the attention of bands of Southern guerrillas. The Civilian & Telegraph opined in late August: “Since the completion of repairs and resumption of navigation on the canal, several boatmen have been plundered of their stock by predatory bands.” These attacks “seriously interfered with the shipments of coal, by giving rise to so great a sense of insecurity among the boatmen as to induce many of them to decline loading.”

The raids interrupted commerce and incensed employees of the C&O Canal Company, who complained of the federal government’s failure to protect the region. In the early fall of 1863, Albert C. Greene, a canal company director, grumbled to canal secretary Walter S. Ringgold, that boating activities around the area of Cumberland had largely ceased. The government, he maintained, had failed “to afford the Boatmen protection against robbery of their teams by the Virginia guerrillas.” Clearly frustrated, Greene continued: “I think it would meet the unanimous approbation of this whole community if Mosby or White or whoever leads these incursions should ride into Washington some fine night and carry off with them to parts unknown Gen Halleck, Sec Stanton and everybody else whose duty it was to prevent these shameful raids.”

The company had cause for complaint, for the impact of the Confederate attacks throughout the summer and fall of 1863 proved financially detrimental. The 1864 annual report of the President and Directors of the C&O Canal Company concluded, referencing Lee’s Pennsylvania Campaign, “damages sustained by this invasion required an expenditure of about $15,000 to restore the navigation and the loss of revenue for two months, which would probably have been not less than $50,000.”

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church is located in the Village of Point of Rocks, Md., where it still offers Sunday services. The church, 1 ½ miles from the Potomac River, served as a staging area and sometimes a hospital for numerous Union cavalry commands from 1862–64. The Federal troopers, in addition to other destruction, burned the 1842 church’s pews and fencing for firewood, tore up the carpet, and turned their horses loose in the graveyard, where they trampled and destroyed gravestones. After the war, the church filed with the U.S. government for $1,691 in damages, and was eventually awarded $1,000 in compensation. A read through the church’s Civil War damage claims, available online at pointorocks.ang-md.org, offers a startling look at the wear and tear of the constant warfare in the Potomac River Valley.

Mosby’s and White’s men were particularly important to Confederate strategy because of their mobility and affect on morale. One Union cavalryman complained, referring to White’s troopers, “on the appearance of any force they disappear.” These tactics were deliberate, for raiders distracted Federals from their “primary objectives, caused them to alter strategies, injured the morale of Union troops, and forced the reassignment of men and resources to counter threats to railroads, river traffic, and foraging parties,” notes historian Daniel E. Sutherland. Two letters issued by Brig. Gen. Henry H. Lockwood regarding the activities of Mosby and White are illustrative of how disruptive raids could be.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The suddenness of the rebel attacks created an illusion of constant peril[/quote]

Lockwood reported to Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck on August 1, 1863, that Mosby and White “with 600 cavalry” were at Leesburg, threatening to cross the Potomac in the area of Point of Rocks. The enemy presence required the reallocation of troops; therefore, Lockwood dispatched 1,000 men “to the Point, to return this morning.” That same day he wrote another Federal officer, Maj. Gen. Darius Couch, commander of the Department of the Susquehanna, and suggested that a lack of coordination among their commands enabled “this contemptible body of irregulars to exist.” As Lockwood’s correspondence demonstrates, countering real or potential guerrilla incursions on or along the canal required significant coordination among commanders, the mobilization of troops, and the use of resources.

Despite Federal protection, the continued raids created panic and inflamed Marylanders’ imaginations demonstrating the psychological repercussions of guerrilla warfare. One example stands illustrative. On the night of August 27, 1863, White and “100 men” of the 35th Battalion Virginia Cavalry crossed the Potomac at White’s Ford. The 11th New York Cavalry, known as Scott’s 900, faced White’s men on the north side of the Potomac. They attacked a strong fortification on William Poole’s farm, opposite Edwards Ferry. “Though being prepared, owing to an attack made by some party upon the canal-boats, I drove them from their fortifications,” White wrote, “the greater part retreating down the river.” The tactics of White’s command and the fear they instilled in Federal garrisons produced a host of similar small-scale victories.

Maryland newspapers quickly issued reports of the partisan incursion. The Civilian & Telegraph, for example, ran an article that stated: “The line of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal is still infested with guerrillas. A large party crossed into Maryland at White’s Ford, on the 28th instant and captured a number of stock” as well as canal teams. Although the number of attackers remained unclear, according to the article “private reports” claimed that the party was 500 strong. The Examiner of Frederick, Md., also printed a piece about the raid: “White’s guerrillas in heavy force, made an attack upon a detachment of ‘Scott’s 900,’ stationed near Edwards’ Ferry.” Rumors of the raid’s size and the extent of damage trickled out slowly by word of mouth or through newspapers, creating much consternation.

As a reporter for the Frederick Examiner noted, “These events created a good deal of solicitude along the river, and through the inflated rumors that rapidly multiplied, caused some nervousness here.” The suddenness of these attacks and the subsequent damage shocked and alarmed nearby residents, thereby creating an illusion of constant peril. Major General J.E.B. Stuart never lost sight of these powerful effects. Writing about White’s actions, he commended the “daring enterprise, which struck such terror to the enemy.”

The Potomac Valley devolved into an environment of war in which the Confederate high command targeted the region’s transportation networks, while Confederate partisans fomented disorder and forced the reallocation of troops and supplies. The Maryland–Virginia border region became an epicenter of contest as early as 1861 as Union and Confederate forces vied for control of the landscape, its manmade improvements, and the region’s rich supplies. Civil war in this area looked different when compared to the great battlefields of Virginia because it was often continuous, lasting months not days. Further, loyalties were often divided along the Potomac River, as communities such as Loudoun County, Va., and Washington County, Md., were rent by war. Although the American Civil War ended for the Potomac Valley in April 1865, residents suffered for years after because of the conflict’s transformative impact upon the land, its resources, and its people.

James J. Broomall is the director of the George Tyler Moore Center for the Study of the Civil War and an assistant professor of history at Shepherd University, and frequently hikes and bikes throughout the Potomac River Valley. He is currently completing a study of white Southern men and their families during Civil War and Reconstruction tentatively titled Personal Reconstructions: War and Peace in the American South, 1840-1880.

A Peaceful Potomac Valley

Mules pulling barges no longer clomp down the C&O Canal towpath along the Maryland side of the Potomac River, but you can use it as a gentle, flat passageway to tour the valley by foot or bike and soak up its history and natural beauty. The C&O Canal National Historical Park (nps.gov/choh/index.htm) maintains the remnant of the 184.5-mile-long canal that ran from Cumberland, Md., to Georgetown, D.C., between 1831-1924, and the section from Shepherdstown, W.V., to Edwards Ferry is particularly rich in Civil War history. You’ll see abutments from bridges destroyed during the conflict, cross over a number of stone aqueducts, including at the mouth of Conococheague Creek and the Monocacy River, that Confederates damaged, and pass by numerous fords used by the armies. Towns that suffered damage during the war like Shepherdstown, Harpers Ferry, Brunswick, and Point of Rocks are all close by, and you can even make reservations to stay overnight in a lockkeeper’s house if you like (canaltrust.org). The Civil War echoes are strong along the river that served as the thin, easily pierced border between North and South. Even though it is close to the heart of the densely populated D.C. corridor, there are isolated stretches along the canal where it is easy to imagine Rebel troopers splashing across to the Maryland shore.-D.B.S.