The Puritans weren’t the only sect to seek freedom to worship in North America

In 1633, 13 years after the Pilgrims disembarked from the Mayflower to establish Plymouth Colony, another band of would-be settlers from England boarded a ship named Ark and set sail from the Isle of Wight. Accompanied by the supply vessel Dove, Ark and its complement headed for Chesapeake Bay, on North America’s mid-Atlantic coast. The travelers intended to develop a colony called “Maryland” on territory carved from the existing Virginia colony.

English law had propelled some Pilgrims across the Atlantic seeking freedom to worship as they pleased. The same restrictions animated Maryland’s founders, who were Roman Catholics and whose goals included establishing a colony that separated state and church—for its era, a revolutionary thought. Nearly 150 years before the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protected religious freedom, Maryland colonial law, in a limited, imperfect, and impermanent way, codified the principle of freedom of worship.

The new colony’s emphasis on religious tolerance didn’t spring solely from idealism on the part of Cecil Calvert, who with his family established and essentially governed Maryland for most of the 1600s as a business enterprise. Cecil Calvert sank every penny he had, and then some, into Maryland. He and his kin saw tolerance as a practical way to keep the peace.

Robert Wintour, an early settler of the colony, embraced Calvert’s vision for a new society, which Wintour dubbed the “Maryland designe.” The attempt at creating and maintaining a distance between religion and politics lasted only briefly and the Calverts had to struggle to keep the colony free of sectarian turmoil, but in time the founders of the United States adopted the principle. In the shorter term a high-stakes tug of war pitted Catholic colonists supported by a royal grant to Cecil Calvert, Lord Baltimore, against a stubborn English Protestant community headed by William Claiborne, who had settled the region prior to the Catholics’ arrival.

Cecil Calvert’s business plan for Maryland called for a diversified economy—farming, lumbering, fishing, fur trading, and mining. Instead, Maryland’s early residents piggybacked on a thriving Chesapeake tobacco trade that Virginians had developed in the 1620s. Marylanders quickly grew to depend on what colonists called “sotweed.” Within three years of arriving in the New World, settlers in Maryland were financially addicted to tobacco, a habit that took centuries to kick. By 1637, tobacco was literally the currency of the colony, officially designated a medium of exchange. Marylanders

bought goods and services, settled debts, and paid tabs to innkeepers in pounds of tobacco. Life in Maryland revolved around planting, cultivating, harvesting, and curing tobacco, an arc punctuated in January and February by the arrival of the tobacco fleet that brought imported goods and carried the season’s harvest back across the Atlantic.

Swings in the market shaped Maryland’s monocrop economy. When tobacco prices plummeted in the late 1650s, landowners responded by growing more sotweed. They did this by improving production methods, and by working indentured servants and enslaved Africans harder.

Calvert’s investment, and his entire Maryland experiment, repeatedly encountered other obstacles. Twice the Calverts lost control of their colony to Protestants from Virginia. One of those foes, William Claiborne, feuded with Cecil Calvert for four decades, supporting armed insurrections and returning to England to ask the king in person that he repeal the charter that granted the Calverts some 12 million acres hacked out of Virginia.

Long before the Calverts had a claim in the New World, the Calvert clan, a noble Yorkshire family, had trod a careful line regarding the family’s Roman Catholic faith. Under Henry VIII, who founded the Anglican Church in 1534 to defy the Pope’s refusal to allow the king to divorce Catherine of Aragon, the Calverts were compelled to embrace Protestantism. Decades later, under King James I, England again tolerated Catholics. George Calvert, the king’s secretary of state, reverted to the Catholicism he had known as a child. George was also named baron of Baltimore, a district in Ireland. After King James died in 1625, George asked the monarch’s son and successor, King Charles, for a royal grant in the American colonies to be named Maryland to honor the king’s wife, Queen Henrietta Maria. Five weeks after George died on April 15, 1632, King Charles I conferred on Cecil Calvert the land grant his father had requested. As the second Lord Baltimore, Cecil intended to do as his father had, balancing faith and fealty to the crown. In settling Maryland, Cecil Calvert assured the king, the Calverts were aiming to enlarge England’s empire in North America, not create a Catholic colony.

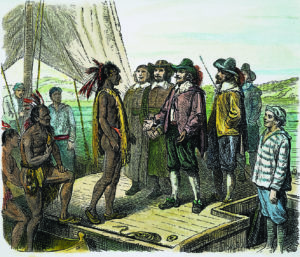

Cecil Calvert organized the party of about 150 men and women that would sail the Atlantic. As the crews of Ark and Dove were making ready, Lord Baltimore, who would not be going along—he never did visit his Maryland holding—ordered his managers and his brother Leonard, the colony’s governor, to sidestep religious divisions: “His Lordship requires that they be very careful to preserve peace and unity amongst all the passengers on Shipp-board and that they suffer no scandal nor other offense to the Protestants, whereby any just complaint may heereafter be made, by them, in Virginia or in England, and for that end, they cause all Acts of the Roman Catholique Religion to be done as privately as may be, and that they instruct all the Roman Catholiques to be silent, upon all occasions of discourse concerning matters of Religion and that the said Governor and Commissioners treat the Protestants with as much mildness and favor as Justice will permit. And this to be observed at Land as well as at sea.”

The colony’s proprietor was aiming his instructions not so much at the Protestants in its ranks as at fellow Catholics, outnumbered 4-to-1 and perhaps inclined to throw their weight around to keep from being bullied. The Catholic contingent included three priests, among them Rev. Andrew White, SJ, of the Society of Jesus, a Catholic order especially loathed by mainstream England.

The Calvert ships sailed in November 1633. Word of Maryland’s establishment had reached Protestant Virginia, founded some 30 years earlier, by late February, when Ark and Dove, needing supplies, docked at Old Point Comfort, Virginia. The Catholics aboard were “full of fear lest the English inhabitants, to whom our plantation is very objectionable, should plot against us,” wrote Father White. Letters from King Charles and the chancellor of the exchequer to the Virginia colony’s governor “served to conciliate their minds,” the Jesuit priest noted. Resupplied, Ark and Dove sailed north to where the Chesapeake Bay met a river called “Potomac,” a European variation of its Indian name.

“At the very mouth of the river we beheld the natives armed,” White reported. “That night fires were kindled through the whole region, and since so large a ship had never been seen by them, messengers were sent everywhere to announce ‘that a canoe as large as an island had brought as many men as there were trees in the woods.’”

From Maryland’s earliest days, Cecil Calvert faced challenges, political and martial. As early as his twenties, William Claiborne, a surveyor born in the English county of Kent in 1577, had owned land and exerted political sway in Virginia. Seeking opportunities, Claiborne sailed north into the Chesapeake to explore and trade with natives. On the estuary’s largest island, across the bay from what is now Annapolis, Claiborne started a fur-trading post. He named the island for his native county and made a pile of money. By the time the Calvert expedition came to establish Maryland, which by royal charter included Kent Island, the settlement there was home to 30-some people. Claiborne, who already had joined other Protestants heaping scorn on the Calverts for their papish ways, chafed at the crown giving his hard-fought turf to Catholics.

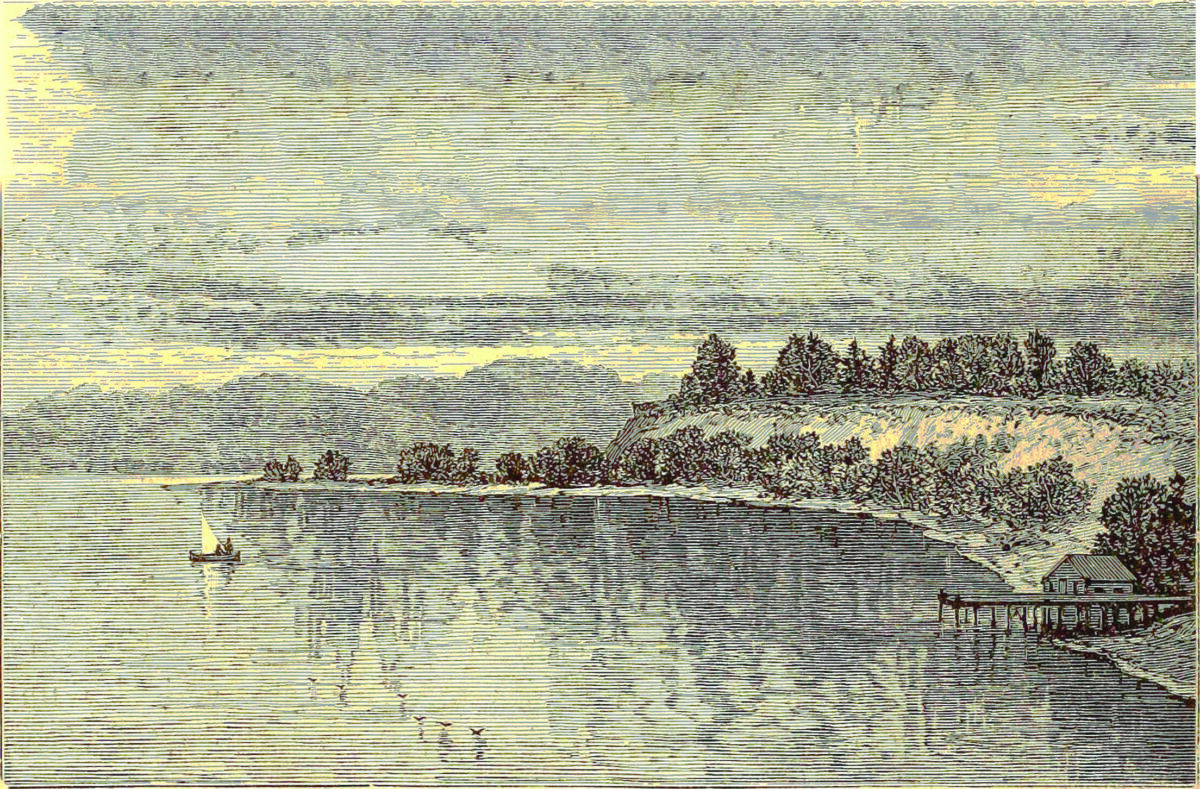

Tacking up the Potomac through a tidewater landscape thick with primeval forest, Ark and Dove anchored off an island the passengers named for St. Clement. The new arrivals used this toehold as a base from which to spend most of March 1634 exploring and negotiat

ing with natives. From the Yaocomaco tribe the colonists acquired, in exchange for tools and cloth, 30 square miles of land on the east bank of a Potomac tributary. On March 25, Father White celebrated that purchase with a Mass on St. Clement’s Island—the first Catholic religious service in the English-speaking colonies.

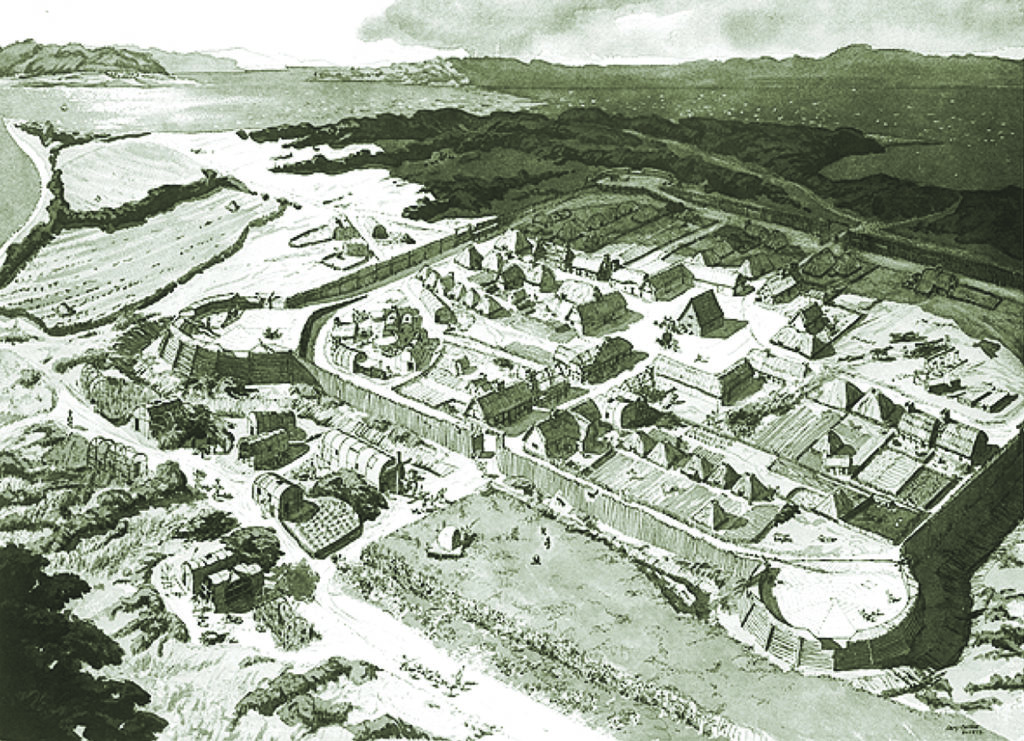

From St. Clement’s Island, the colonists moved to a location on their newly acquired parcel where the Yaocomaco coincidentally happened to be abandoning a hamlet of 10 to 12 cleared acres and two dozen habitations. The English renamed the property St. Mary’s City and the river on whose banks it stood the St. Mary’s. Across the river was a large Indian settlement to which the hamlet’s former inhabitants moved. St. Mary’s City, high and defensible, had freshwater springs. There were no swamps nearby. The Yaocomaco now had allies with guns, should hostile tribes raid, and were willing to show the new neighbors how to plant corn. The Maryland colony began in amity—for a while.

The dispute with Claiborne over Kent Island festered. Claiborne refused to leave his settlement, which now included a plantation. He also refused to recognize Maryland’s claim to the island. His supporters fought with but could not defeat Calvert’s forces. While Claiborne was in England arguing his case, Maryland seized Kent Island, a takeover endorsed in 1638 by the Lords Commissioners for Plantations, a board in England that oversaw New World settlements. The Calverts offered to allow Claiborne to keep his trading post if he paid his new masters a percentage of the profits, further enraging him.

Events in England echoed in Maryland. In 1642, civil war, partly over religion, broke out between King Charles and Parliament. Cecil Calvert sided with the king, inflaming animosity between Protestants in Virginia and Catholics in Maryland, who though a minority held most of the political power. Leonard Calvert went home to England to consult with his elder brother. In Leonard’s absence, the acting governor ordered the arrest of Richard Ingle, a Virginia tobacco trader who had been heard to say that Charles was no proper king. Leonard’s stand-in charged Ingle with high treason for that imprecation. Ingle escaped and fled to England. With Parliament’s backing, he returned in 1645 to invade Maryland aboard the ship Reformation. Ingle and his men seized the colony, destroying or stealing prominent Catholics’ property in what came to be called “the plundering time.” Joining forces with Ingle, Claiborne retook Kent Island.

Governor Leonard Calvert fled to Virginia. Ingle transported prisoners, including Father White, to England, where he accused the Catholics running Maryland of conspiring to disarm Protestants there. In London, Cecil Calvert worked to fend off efforts to revoke Maryland’s royal charter. In 1647, Leonard Calvert recruited a force of Maryland refugees and likeminded Virginians and took back Maryland, now depopulated and badly weakened. Leonard died that year; to replace him, Cecil appointed a Protestant, William Stone, and named other Protestants to colonial offices. Parliamentary forces now ruled England; Cecil was gambling that his Protestant agents would remain loyal to him and deflect anti-Catholic sentiment from him.

To rebuild and restabilize Maryland, Stone recruited Protestant immigrants, including Puritans, who were unwelcome in Virginia because of their criticism of what they alleged to be traces of Catholicism in the Anglican church. This policy left Maryland Catholics even more badly outnumbered. In January 1649, King Charles I, the Calverts’ royal patron, was beheaded. Lord Baltimore was determined to draw more people to Maryland by guaranteeing that residents could practice their religions. Cecil Calvert proposed and the Maryland assembly adopted the Act Concerning Religion, the legislative legacy of George Calvert’s desire to avoid religious strife in his colony and to protect the rights of Catholics. No one in Maryland “shall from henceforth bee any waies troubled, Molested or discountenanced for or in respect of his or her religion nor in the free exercise thereof,” the law decreed, “nor any way compelled to the beliefe or exercise of any other Religion against his or her consent.”

The language about free exercise of religion set a precedent later enshrined in the Bill of Rights. In the 19th century, popular historians began to call the law Maryland’s Act of Toleration to emphasize that linkage. Though unique in English or colonial law of the time, the Act Concerning Religion, by modern standards, rings deeply restrictive. The law’s protections applied only to those professing belief in Jesus Christ and the Trinity. Non-Christians, and for that matter Unitarians, could find no succor in it. Anyone cursing the deity or denying the Trinity or the divinity of Jesus “shalbe punished with death and confiscation or forfeiture of all his or her lands and goods to the Lord Proprietary and his heires.” Anyone “uttering reproachful words” about the Virgin Mary, apostles or evangelists could be fined five pounds, and if they didn’t quickly pay up, they could be publicly whipped and imprisoned. On the other hand, anyone speaking to someone else “in a reproachful manner” about religion risked a fine of 10 shillings, with half the levy to go to the target of the reproachful remarks, the other half to Cecil Calvert. No records are known to exist of any successful prosecution under the Act.

The Act Concerning Religion, enacted in part to entice Puritans to settle in Maryland, failed to stabilize the society Cecil Calvert was hoping to create, thanks once again to events across the sea. The Puritans governing England set up a commission, whose members included William Claiborne, “to reduce all plantations within the Bay of Chesapeake to their due obedience to the Parliament of the Commonwealth of England.” Maryland was not specifically mentioned, but after bringing Virginia into line Claiborne in 1652 invaded Maryland and took control of the colonial government. He and his allies pressed Parliament to rescind Lord Baltimore’s charter for Maryland and to restore those lands to Virginia. In 1654, Calvert’s Act Concerning Religion was replaced by a law that denied religious, economic, and political rights to Catholics and certain other Christians.

During this arduous time, Cecil Calvert was in London, hard at work protecting his holdings. The fray came to include Oliver Cromwell, the Puritan lord protector ruling England, Scotland, and Ireland. To Cromwell Calvert emphasized his intent to restore and enforce the original 1649 Act Considering Religion, which appealed to Cromwell’s goal of protecting the right to worship other than at the Church of England. Cromwell in 1657 backed a treaty between Maryland and Virginia that returned control of Maryland to the Calverts.

Cecil Calvert recommitted his colony to religious tolerance—provided colonists respected his role as proprietor—and said that no law should be passed contradicting the Act Concerning Religion. During this period, the colony’s Protestant attorney general, Henry Coursey, attempted to prosecute individuals under the law.

Coursey charged the Catholic priest Francis Fitzherbert, SJ, with trying to force the Protestant wife and children of a prominent Catholic to attend his church. The Jesuit argued that the Act Concerning Religion protected preaching and teaching, and the court agreed.

In 1658, Coursey charged Jacob Lumbrozo, a Jewish physician and landowner who had immigrated from Portugal, with blasphemy, alleging Lumbrozo denied Jesus Christ’s divinity. Testimony indicated that Puritans had baited Lumbrozo into attributing miracles mentioned in the Bible to necromancy or sorcery and rejecting the Resurrection by arguing that after the Crucifixion Christ’s disciples spirited his body away. For these ostensible utterances, Lumbrozo faced the death penalty.

But the case never came to trial. The colonial governor, honoring the ascent of Oliver Cromwell’s son, Richard, to lord protector, issued a general pardon that extended to Lumbrozo, not only saving his life but preserving his citizenship. The once-besieged physician got a license to operate an inn, did business with Indians, and served on juries.

For two decades, the Act Concerning Religion worked as intended to preserve the peace and discourage religious conflict. Cecil Calvert died in 1675. His son, Charles, became the third Lord Baltimore and the colony’s proprietor. When at 77 William Claiborne made a last attempt in 1677 to regain Kent Island, King Charles II, installed in the 1660 Restoration, rebuffed him. Claiborne died shortly thereafter. In Maryland, peace and prosperity in the colony that he inherited lulled Charles Calvert into complacency. A less politically savvy manager than Cecil, Charles named primarily Catholics and Protestant relatives of his family to colonial posts, feeding resentment among his enterprise’s less affluent Protestant citizens and poising Maryland to be rattled again by reverberations from the mother country.

Catholic King James II was deposed in 1689. Parliament gave the crown to his daughter, Mary, and son-in-law William of Orange, both Protestants. Charles Calvert, in England at the time, wrote to Maryland ordering officials there to recognize William and Mary as monarchs. That message never arrived. Disgruntled colonists used the lag in recognizing the Protestant royals as a pretext to revolt and seize the colonial government. The colony’s new Protestant government established the Church of England as Maryland’s official religion through legislation nullifying the 1649 Act Concerning Religion. Charles Calvert lost claim to the colony conceived by his grandfather and created by his father. By the time Charles died in 1715, Catholicism in Maryland had been driven underground. The Calverts got the colony back only after Charles’ son, Benedict, the fourth Lord Baltimore, renounced his Catholic faith and became a Protestant. It took the Revolutionary War and adoption of the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights to guarantee freedom of religion in Maryland again.

_____

History at Hand

Maryland colonists’ first settlement is now an 800-acre museum, Historic St. Mary’s City. Features include archaeological digs, a replica Dove, a reconstruction of a brick chapel, and recreations of a tobacco plantation and a Yaocomaco hamlet. Living history exhibits are open mid-March through November. Historic St. Mary’s City is about 70 miles southeast of Washington, DC [hsmcdigshistory.org]. Nearby St. Clement’s Island Museum on the Potomac shore adjoining its namesake land mass focuses on early Maryland history and the state’s riverine heritage—[www.stmarysmd.com/recreate/stclements-island]. St. Clement’s Island itself, where the passengers and crew of Ark and Dove first landed, is a Maryland state park and is accessible by boat. Tour boats depart from the museum weekends in season. Sotterley Plantation, built about 1703, is open in season; visitors can tour the plantation house and gardens, as well as the places where enslaved African-Americans lived and worked [www.sotterley.org]. Point Lookout, a state park where the Potomac River meets Chesapeake Bay, includes a recreation of portions of a Civil War prison camp that held Confederate POWs [bit.ly/pointlookoutpark]. In Lexington Park, eight miles north of St. Mary’s City, Patuxent River Naval Air Museum chronicles naval aviation since World War II, with special attention to the military test pilots trained at Patuxent River Naval Air Station who became astronauts [www.paxmuseum.com]. —Rick Boyd