One of the more touching and little-known mascot stories of the Civil War is that of “Major,” described as a “large black Newfoundland cross-breed dog,” weighing about 110 pounds.

Major had his first experience in the war while with the 2nd New Hampshire Infantry and was with them at the First Battle of Bull Run. During the battle on July 21, 1861, Major received a slight wound and afterward would return with the regiment to Portsmouth, N.H.

But on October 6, 1861, he volunteered again, jumping aboard a southbound train containing a newly recruited two-year regiment, the 10th Maine Infantry. He followed Captain Charles Emerson of Company H into the train car and was immediately adopted by the men of the company and given the name “Major.”

Loved by Union and Confederate Soldiers

Recommended for you

A comrade recalled that while the 10th Maine was stationed at the Relay House railroad transportation hub near Baltimore in November 1861, Major “was always among the most advanced of the pickets, and no dog was ever allowed to cross the lines with impunity.”

On December 6, 1861, Captain George H. Nye of Company K, 10th Maine, penned the following to his wife, Charlotte: “We have some domestic animals in the house –first-we have a dog-weighs about a hundred pounds–he is on the sick-list today–he has a great dislike for the engine as the engineer squirted some water on him the other day, since then whenever he sees the cars coming he puts for the engine on the clean jump. Today he got a little too near and the cow-catcher gave him a pretty hard thump—knocking off a piece of his nose and his rump….I guess tomorrow he will get up in good shape and be a wiser dog.”

On May 25, 1862, during Union Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks’ retreat following the First Battle of Winchester, Major was so crippled by the long march that he could hardly walk and was eventually captured and spent two days behind Confederate lines before “escaping” to rejoin his comrades in Company H.

Recounting the September 1862 Battle of Antietam, regimental historian Lieutenant John Mead Gould wrote, “Old dog ‘Major’ behaved well under fire, barking fiercely, and keeping up a steady growl from the time we went in till we came out. He had thus contributed his part towards the uproar which some consider so essential in battle. He had shown so much genuine pluck, moreover, that the men of H were bragging of his barking, and of his biting at the sounds of the bullets, asserting besides that he was ‘tail up’ all day.”

A comical—though potentially fatal—trait began to be observed of Major during battle: He would leap into the air to snap at bullets as they whizzed by or as they created small dirt clouds when they hit the ground.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Fetching and Fighting

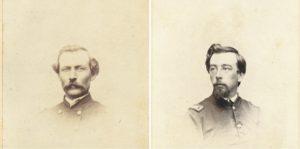

wounded at Nashville, as was Harvey. (USAHEC)

MAJOR, OF COURSE, was not the only dog to find a deserving home as a regimental or company mascot in either the Union or Confederate armies. There were several famous ones—including “Jack,” a stray bull terrier adopted by the Pittsburgh-based 102nd Pennsylvania Infantry. According to the regiment’s soldiers, many of them former members of Pittsburgh’s Niagara Volunteer Fire Company, Jack would join them on the march and would stand near the “firing line” during combat. Jack, they stressed, comprehended bugle calls and would obey orders. He was also known to roam the battlefield in the wake of fighting, seeking out wounded and dead “comrades.” Captured twice, Jack at one point survived six months in a Confederate prison camp.

Another canine mascot of note was “Sallie,” a brindle Staffordshire bull terrier adopted by the 11th Pennsylvania (remembered with the memorial below). Sallie was with the regiment at Gettysburg, famously standing guard over wounded or dead Federals on Oak Ridge during the battle, and thereafter survived several intense engagements before being killed in action at Hatcher’s Run, Va., in February 1865. She was, appropriately, buried on the battlefield.

A white bulldog named “Harvey” (shown right) was a mascot of the 104th Ohio—the so-called “Barking Dog Regiment”—and was wounded in action at Kennesaw Mountain during the Atlanta Campaign and later at Nashville. And let’s not overlook “York,” who faithfully accompanied Union Brig. Gen. Alexander S. Asboth, joining him at Pea Ridge and during the Siege of Corinth, Miss. Or “Calamity,” known as a foraging specialist with Company B of the 28th Wisconsin. Just a few! For those of us with cherished dogs who, yes, shrink and hide at the sound of thunder or fireworks, we salute these canine anomalies.

A Fellow Mainer

Major returned home to Maine with the two-year enlistees of the 10th Maine, and the regiment was mustered out on May 8, 1863. News of the dog’s deeds in the war had spread to his native New Hampshire, and the veterans of the 10th Maine faced an attempt by his former master to claim Major as his property. The men of Company H offered to purchase the dog at the owner’s price, but he insisted on having the dog returned. Emerson refused to return Major, and the owner next appealed to Colonel George L. Beal, the regimental commander.

Beal refused to get involved, saying the matter did not concern him and insisted the owner settle Major’s ownership with the men of Company H. While the dog’s owner was meeting with Beal, two of the Company H men took Major away from camp and kept him out of sight. The owner was forced to return home without his dog or the money the men had offered.

The soldiers paid to have a silver collar made for Major. On the collar was engraved an oak leaf, signifying the rank of major. Also inscribed on the collar were the battles in which Major participated.

The collar was given to 1st Lt. Granville Blake, who assumed responsibility for Major after Emerson became lieutenant colonel, keeping Major at his home in Auburn, Maine. On December 16, 1863, Blake was commissioned a captain in Company H of the 29th Maine Infantry, made up of many 10th Maine veterans, including the faithful Major.

Major accompanied Blake and the 29th Maine to New Orleans, arriving on February 16, 1864. They would take part in Banks’ ill-fated Red River Campaign. It would be Major’s second campaign with Banks—and his last.

Major goes Missing

In late March 1864, Major went missing for a short period. Gould wrote in his journal: “The dog Major is lost: was last seen in Washington [Louisiana] where he went in swimming with the Reg’t. In the 10th he used to march at the head of the Reg’t. as Company H was on the right but in the 29th H is near the left and old Mage is wild when it comes marching time….” Shortly afterward, Major returned to the regiment.

On April 8, 1864, the 29th Maine entered the fight at the Battle of Mansfield. While positioned at Chapman’s Bayou, also known as the “plum orchard fight,” Major was barking fiercely at passing stragglers.

Major’s Death

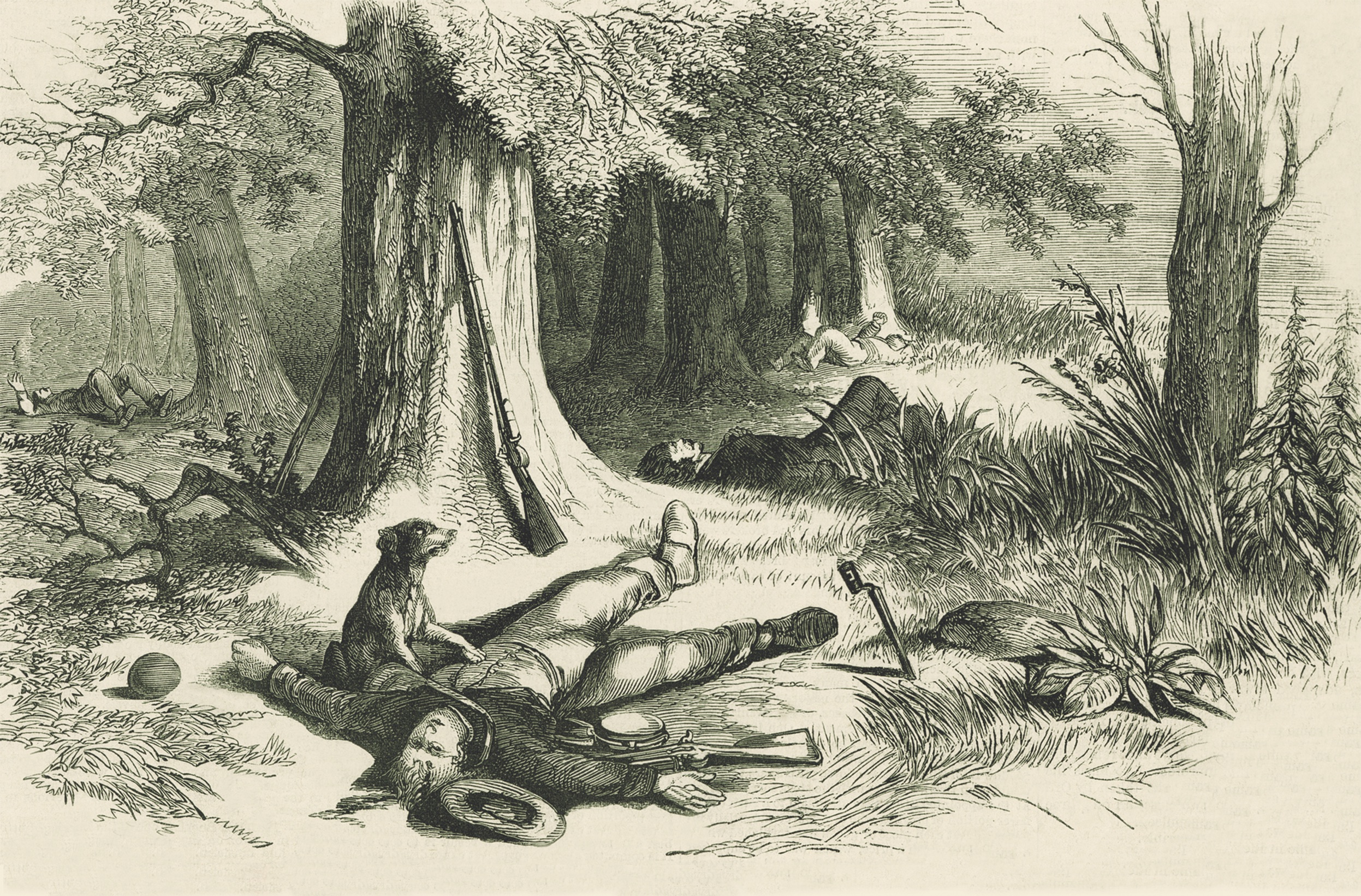

In a tribute to Major in his 1871 regimental history, Gould wrote: “He was always a dog of singular behavior, but never acted so strangely as in his last fight. While in camp at the saw mill he was much disturbed at hearing the sound of the battle, and appeared to know that we should have to, or ought to go to the front. He barked wildly at every cavalry-man we met on the march[,] he seemed to know a straggler and skulk, and knew, too, that it was safe to bark at them. We never shall forget his actions at the top of the hill where we fought. As before stated, we came at that point upon almost a solid mass of fugitives, and here, too, we first heard the bullets whistle. The dog seemed to comprehend the situation, and bracing himself against the torrent, he gave one long, loud howl that rose above all other sounds, and then went on again. He ran wildly around the field, always keeping in our front, and biting at the little clouds of dust raised by the enemy’s balls. At our first volley he jumped into the air, howled and bit at the flying bullets, and was going through strange capers when the fatal bullet struck him. He died like a hero, far in the front of the line, and had he been human we should not have felt his loss more keenly.”

In a letter home written shortly after the battle, Nye, then commanding the 29th Maine’s Company K, poignantly summed up Major’s death:

Our old dog Major which was such a great favorite with us was killed at the battle of Mansfield in the first days fight—he fell just in front of my company, he was running in front of the company jumping for the bullets as they knocked up the dust in front of us. We miss him very much for we were all greatly attached to that poor fellow—but he fell on the field of battle nobly facing the foes.

Major would share the fate of many a soldier, whether they wore blue or gray: an unmarked grave on the battlefield.

Nicholas Picerno is chairman emeritus of the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation and has been collecting and researching the 1st, 10th, and 29th Maine Infantry for more than 40 years.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.